Can Stan McChrystal’s Campaign Be Saved?

The nail-biting saga of General Stanley McChrystal’s Rolling Stone interview has riveted a wide audience whose interest in Afghanistan had otherwise flagged. Shortly we’ll know whether he keeps his job, and the hyperventilating will subside over civil-military relations (On life support? Healthier than ever?).

The nail-biting saga of General Stanley McChrystal’s Rolling Stone interview has riveted a wide audience whose interest in Afghanistan had otherwise flagged. Shortly we’ll know whether he keeps his job, and the hyperventilating will subside over civil-military relations (On life support? Healthier than ever?).

McChrystal’s personality aside, however, the American government needs to figure out something much more urgent and important: Is his counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan working? Based on what we’ve learned in the last year, can it work at all?

President Obama hired McChrystal to turn around a war that had stagnated. He was chosen to execute a nimble counterinsurgency strategy, a campaign designed to stabilize Afghanistan and win popular support among Afghanis, harnessing military, political and economic policy.

The prior strategy wasn’t working – the Taliban had made a dramatic comeback in the years since the original invasion in 2001. Even the most vocal proponents of counterinsurgency doctrine cautioned that it had no guarantee of succeeding. To give counterinsurgency a fighting chance might require more troops, money and time than the United States was willing and able to give. (That caveat presaged some early advocates’ current view that there were never enough resources tasked to make a COIN campaign viable.)

Now the U.S. is a year into McChrystal’s plan: the halfway point to the summer of 2011 when the surge is supposed to end and American troop numbers will be reduced. So much has gone off script, however, that it raises questions about whether McChrystal’s blueprint still applies.

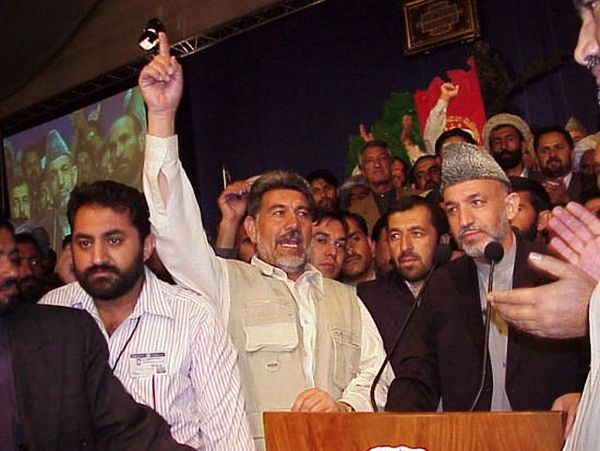

- President Hamid Karzai has broken ranks, frequently attacking his U.S. patrons in public.

- The Taliban has gotten stronger militarily.

- The first showcase offensive in Marjah has so far failed to stabilize the town or deny the Taliban sanctuary there.

- This summer’s major showcase offensive in Taliban-dominated Kandahar has been indefinitely postponed.

- Pakistan has derailed efforts to negotiate with the Taliban, even arresting the Taliban’s number-two when he held clandestine meetings with the United Nations.

All these events don’t prove that the U.S. can’t achieve its aims in Afghanistan – but that’s the conclusion to which they’re beginning to point. Counterinsurgency defines the toolkit the military brings to the fight; it doesn’t actually answer the question of what America should do.

Over the next year, if it hopes to establish some lasting stable order in Afghanistan, America will need a far greater unity of effort between its generals, its diplomats, its special envoys, and its friends in the Afghan and Pakistani governments. With or without McChrystal, the United States will have to make course corrections in Afghanistan as the war unfolds.

Quick briefing materials

Fred Kaplan at Slate argues that McChrystal and his loose-lipped team reveal a war effort spinning of control.

Leslie H. Gelb at The Daily Beast argues that the Democratic Party suffers from a permanent culture clash with the military.

Andrew Exum writes a thoughtful post about whether the assumptions behind the current strategy in Afghanistan still hold up. He also struggles with the implications of firing/not firing McChrystal in these two posts.

In the “Is History Repeating Itself?” department we have Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s post-mortem on the last general fired from running the Afghan year, just about a year ago.

And finally, the Michael Hastings article in Rolling Stone that kicked off the fuss, and which – the scandal aside – raises pointed questions about whether the counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan makes any sense.

The Afghanistan Endgame

Brian Katulis at the Center for American Progress and Andrew Exum at the Center for New American Security tangled this week over Afghanistan strategy. Brian said the counter-insurgency community had hoodwinked Washington, and Andrew said that the Center for American Progress hadn’t presented compelling plans for Iraq and Afghanistan. Michael Cohen prompted the kerfuffle when he argued that the left had failed to question the war in Afghanistan and propose credible alternatives.

All of which got me thinking: can the think tank community propel a smart, substance-focused public debate about America’s strategic aims in Afghanistan? I have in mind a probing, impolitic assessment of whether the current tactics can achieve that strategy. CAP invited CNAS to take part in a public debate, which Exum said he we would happily join after returning from a dissertation leave. But I’d like to see these thinkers applying their brains to the big sprawling questions. Think tanks are largely extensions of different power constituencies in Washington, so perhaps it’s naïve, or structurally impossible, to expect them to re-frame the Afghanistan debate so that it includes more than the current two options: leave, or stay and fight, with some debate over the timeline and number of troops.

I expected this kind of vigorous reappraisal in 2009, during the Obama Administration’s Afghanistan policy reviews. However, the government ended up focusing on narrow questions, like how many troops were required to execute a counter-insurgency strategy, and on what timeline American troops should withdraw. The public never heard an airing of the underlying strategic questions:

- What tactics have been most effective at killing, capturing or deterring individuals and organizations whose goal is to conduct terrorist attacks beyond Afghanistan’s borders?

- What is America’s desired end-state in Afghanistan and Pakistan? Is it achievable, especially considering Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s drift away from the U.S. and Pakistan’s internal problems?

- If not, can America disentangle itself from Afghanistan in its tenth year of war there, even without achieving its principal war aims?

- If the U.S. cannot midwife a stable Afghanistan (or Pakistan) then what is the most effective way to combat the international terrorist groups currently thriving in the borderlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan?

These questions are tough, and probing honest answers would probably require the defense and South Asia experts to jettison some of their previous conclusions and criticize the policies of some of their friends and colleagues. But it would be a healthy and illuminating discussion at a moment when the course set largely by General Stanley McChrystal’s report last fall seems not to be yielding the desired results.

One way Afghanistan could end up in a handbasket

This week, my graduate students at the New School ran a simulation of the coming year in Afghanistan. I kept the parameters loose and tracked the scenario closely to reality. (I’ve attached a list of the roles assigned at the end of this post.) They began in the present, April 2010, tasked with finding a way to minimize the amount of casualties and political instability before the summer. In a second round of play, set in July, the scenario stipulated that ISAF had invaded Kandahar without conclusively wresting control of the city from the Taliban. In the final round of play, set in October, the US was tasked with trying to usher in a settlement between the Afghan government and the insurgency.

Keep in mind that it’s only a game, but the results surprised me:

- India and Pakistan reached secret agreements over trade routes and insurgent funding.

- In the game, the U.S. played the most active role in brokering settlements between competing Afghan factions.

- Prompted by payments from the U.S., unsuccessful presidential candidate Abdullah Abdullah formed an alliance with Northern Alliance leader and defense minister Marshal Fahim, and the pair then made a secret deal with insurgent leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

- Ahmed Wali Karzai, joined forces with disaffected Afghans and the CIA to plot a coup and assassination of his brother the president.

- In the final negotiations to set the terms for a new election, Taliban factions and other insurgents won a deal in which they agreed to take part in the ballot without being forced to renounce violence, and without any guarantees that they would honor the results.

- The U.S. was unable to resolve terms for how it would operate and fund a government that included Taliban, especially if the Taliban won the scheduled elections.

Of course, there are countless differences between a simulation game like this one and reality, not the least of which is that players who in real life would have difficulty passing simple messages through third parties can in the game easily converse with one another. Some lessons I took:

- If communications channels opened up, some hostile parties like India and Pakistan could find common ground on incremental details.

- Insurgents had a strong hand negotiating deals with the Afghan government and the U.S.; they could come to favorable terms and then defect as soon as it suited them with few consequences.

- The U.S. was severely constrained by the quality and reliability of its allies. It had no compelling alternative to Karzai. The Abdallah-Fahim-Hekmatyar alliance, far-fetched as it was, was inherently unstable and not likely to result in a stable government that could advance U.S. interests or secure Afghanistan.

- As in real life, it seemed like there were no good possible outcomes, only varying degrees of bad.

- Too many actors with two few constraints have the ability to destabilize Afghanistan and Pakistan. Even a brilliant and well-executed strategy would have difficulty accounting for all the different Afghan factions and regional players.

The players:

| CIA Kabul station chief |

| US Ambassador Karl Eikenberry |

| General Stan McCrystal |

| Richard Holbrooke |

| President Hamid Karzai |

| Ahmed Wali Karzai, President Karzai’s brother, Kandahar strongman |

| Marshal Mohamed Qasim Fahim, defense minister, Tajik Northern Alliance leader |

| Abdullah Abdullah, failed 2009 presidential candidate |

| Mullah Abdul Qayyum Zakir, deputy supreme leader, Taliban/Quetta Shura |

| Sirajudin Haqqani, leader of Haqqani network |

| Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leader of Hezb-e-Islami militant faction |

| Local Popolzai chieftain, leader of unaligned Pashtun sub-tribe |

| Ashfaq Kayani, Pakistani army chief of staff |

| Lt. Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha, director-general of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency |

| Shri S.M. Krishna, External Affairs Minister, India |

| Manouchehr Mottaki, foreign minister, Iran |

| Sergey Lavrov, foreign minister, Russia |

| UN Special Representative Staffan de Mistura (Sweden) |

| UN deputy Special Representative for Politics Martin Kobler (Germany) |