Are we all interventionists now?

[Published in War on the Rocks.]

Ever since Russia reneged on an ill-conceived ceasefire plan for Syria in September and participated in a barbarous military campaign in Aleppo, the crescendo of American voices calling for some action in Syria has risen a notch, apparently reaching the White House this week.

Throughout the Syria crisis, the U.S. government bureaucracy and key power centers in the foreign policy elite have espoused Obama’s version of restraint and resignation, toeing a position along the lines of “Syria is a mess, but there’s little we can do.” Lately, though, an escalatory mindset has taken hold, with analysts and politicians floating proposals to defend Syrian civilians and confront an expansionist Russia.

“I advocate today a no-fly zone and safe zones,” Hillary Clinton said in the most recent debate, taking a position starkly more interventionist than the president she served as secretary of state. She continued: “We need some leverage with the Russians, because they are not going to come to the negotiating table for a diplomatic resolution, unless there is some leverage over them.”

Does this kind of talk represent a sea change in decision-making circles? After years of decrying missteps in the ill-begotten wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and debating America’s shrinking footprint, is there now a convergence to once again embrace interventionism among politicians, public opinion and the foreign policy elite that some in the White House derided as “the blob”?

I think there is, and those of us who have espoused a more vigorous intervention in Syria and a more activist response to the Arab uprisings need now to take extra care in the policies we propose. As the pendulum swings back toward a bolder, more assertive American foreign policy, we must eschew simplistic triumphalism and an unfounded assumption that America can determine world events. Otherwise we risk repeating the mistakes of America’s last, disastrous wave of moralism and interventionism after 9/11.

It’s important not to overstate the backlash to Obama’s calls for humility and restraint, and not too ignore the activist and moralistic strains that connect Obama’s foreign policy to that of his predecessors. With those caveats, it seems like we’re on the cusp of a return to a more activist foreign policy.

That doesn’t make us all interventionists yet, but it does expose the United States to renewed risk, making it all the more important to restore some honesty and clarity to the debate. Any discussion about America’s global footprint has to acknowledge that it’s still huge. America has not retrenched or turned its back on the world. Any discussion about Syria has to acknowledge from the get-go that America already is running a billion-dollar military intervention there. So when we talk about escalating or de-escalating, we need to be clear where we’re starting. The United States is heavily implicated in all the Arab world’s wars, with few of its strategic aims yet secured. This unrealized promise has fueled frustration about America’s role.

Even Trump’s isolationist calls to tank the international order and make America great by impoverishing the rest of the world echo, in part, a desire for strength and moral clarity. The likely next president, Hillary Clinton, has steadily stood in the American tradition of liberal internationalism which has been the dominant school of foreign policy thought since World War II. That history embraces an international order dominated by the United States and trending toward market economies, free trade, liberal rights, and a rhetorical commitment to freedom, democracy and human rights, which even in its inconsistent and opportunistic pursuit, has been considered anything from an irritant to a major threat to the world’s autocracies. This ideological package has underwritten America’s best foreign policy, like Cold War containment, and its worst, like the invasion of Iraq and the post-9/11 savaging of the rule of law.

Syria’s war has been the graveyard of the comforting, but vague, idea that America could lead from behind and serve as a global ballast while somehow keeping its paws to itself. Other destabilizing realities helped upend this dream, among them Europe’s financial crisis, the rise of the extreme right, the Arab uprisings, the collapse of the Arab state system and a new wave of wars, unprecedented refugee flows, and the expansionist moves of a belligerent, resurgent Russia.

Pointedly, however, Syria has embodied the failure of the hands-off approach. Its complexity also serves as a warning to anyone eager to oversimplify. Just as it was foolish to pretend that the meltdown of Iraq and Syria, and the rise of the Islamic State, were some kind of local, containable imbroglio, it is also foolish to pretend that a robust, interventionist America can resolve the world’s problems. Neither notion is true.

America is the preeminent world power. It can use its resources to manage conflicts like Syria’s in order to pursue its interests. Success flows from clearly defining those interests and intervening sagely, in a coordinated fashion across the globe. America has played a disproportionate role in designing the international institutions that created a new world order after World War II. For a a time after the end of the Cold War, it enjoyed being alone at the top of the global power pyramid. American influence swelled for many reasons, highest among them American wealth, comprehensible policy goals, and appealing values. But dominance is not the same thing as total control, and a newly assertive U.S. foreign policy still can achieve only limited aims.

The next president will have to recalibrate America’s approach to power projection – how to deter powerful bullies like Russia, how to manage toxic partnerships with allies like Saudi Arabia, how to contain the strategic fallout of wars and state failure in Iraq, Syria, and the world’s ungoverned zones. The most visible test right now is Syria. Syria is important – not least because of the 10 million displaced, the 5-plus million refugees, the half million dead. It is also important as the catalyst of widespread regional collapse in the Arab world, the source of an unprecedented refugee crisis, a hothouse for jihadi groups, and as a test of American resolve.

It’s harder and harder to find foreign policy experts willing, like Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson recently did inThe New York Times, to argue that any American effort to steer the course of Syria’s war will only make things worse. (British journalist Jonathan Steele made a similar argument this week in The Guardian that any Western effort to contain war crimes in Aleppo “threatens to engulf us all.”)

Figures from both major U.S. parties have increasingly shifted to arguing that the United States will have to experiment with some form of escalation, because the existing approach just hasn’t worked. Hillary Clinton’s team is apparently considering a range of options including no-fly zones or strikes on Syrian government targets. The ongoing shift is less the result of a revelation about Syria’s meltdown and more a reflection of American domestic politics and a consensus that it’s time to recalibrate America’s geostrategic great power projection.

As this debate gets underway in earnest, it is crucial to force all sides to draw on the same facts, and be honest about the elements of their policy proposals that are guesses. For example: It is a fact that Syria is in free fall and Iraq barely functions as a unitary state, with fragmenting civilian and military authority on all sides of the related conflicts. It is a guess that Russia has escalation dominance and is willing to pursue all options, including nuclear conflict, if the United States intervenes more forcefully in Syria. It is a fact that tensions between the United States and Russia are at a post-Cold War high. It is a guess that they will clash directly over Syria rather than Kaliningrad or Ukraine or some other matter. It is a fact that the rise of the Islamic State and the flow of millions of displaced Syrians has destabilized the entire Middle East and reshaped politics in Europe. It is a guess that if the United States shoots down some of Bashar al-Assad’s helicopters it will lead to more fruitful political negotiations among Syrian factions and their foreign sponsors.

Many of the competing poles of the American debate begin with assumptions that are shaky or downright false, and ignore the lion’s share of facts on the ground in Syria. Any honest assessment of the crisis demands humility. Any serious analyst taking a position on Syria has to acknowledge that there is no possibility of a neat solution, and no outcome that precludes civilian suffering, regional instability, and strategic blowback — whether one argues for increasing America’s intervention, as I have, or for further restraint, in keeping with President Obama’s position (or, for that matter, for an admission of rebel defeat and an acceptance of Bashar al-Assad’s enduring role).

Unfortunately, many interventionists ignore the low likelihood of success and the danger of escalating the war, while many restrainers downplay the major ongoing strategic risks posed by Syria’s meltdown. Marc Lynch, himself of the school of restraint, neatly dissected the incoherent underpinnings of the American debate in a recent War on the Rockspiece.

America cannot direct the course of events in Syria because the war is too complex and Russia too committed to Assad, Lynch argues. But with the regime’s war crimes accelerating, for political reasons America can no longer afford to be perceived as not trying harder, even if any extra effort is destined to fail. Lynch predicts that Hillary Clinton will win the presidency and pursue an escalation in Syria, which will fail for all the same reasons as America’s existing intervention. In a year’s time, Lynch argues, Syria will be worse off, and America will either back down or sink deeper into yet another doomed Middle Eastern war.

Sadly, Lynch might be right. But – and the tone of certainty in all the polemics and analysis makes it easy to forget – he might also be wrong. Happily, for the prospects of the debate over Syria, Lynch offers an example of striking the right tone. He is confident in his analysis but not sloppy with the facts. Now that escalation is more seriously on the table, we need a more honest debate.

While Lynch contributes a welcome measure of sobriety to the debate, even he sidesteps the initial fact that Obama’s policy has been to pursue a military intervention, leaving the implication that the status quo doesn’t somehow involve a major U.S. role in the Syrian war. That gets to the heart of the problem: Anti-interventionists won the internal debate in the Obama administration, swatting down proposals from cabinet members to expand the U.S. role, strike Assad when he used chemical weapons, and push harder for regime change. Instead, a Goldilocks notion of the “just-right” intervention governed U.S. policy in Syria since 2011 — enough to say we did something, not enough to be determinative. Yet this policy’s authors often present themselves as an embattled minority facing down the interventionist blob — a foreign policy establishment caricatured as prone to groupthink and which never met an intervention it didn’t like. The actual debate is between limited interventionists like Obama and expanded interventionists like Clinton. On the far ends are those who want a full withdrawal from the Levant and the mad hawks who’d like to see U.S. troops foment regime change in Damascus.

No serious position on Syria can ignore America’s existing, major and ongoing military intervention, or the frustrating reality that the United States and its allies tried and failed to steer the conflict in another direction. No serious position on Syria can ignore the war crimes, sectarianism, and intractability of Assad and his supporters. No serious position on Syria can ignore the very real risks of a direct conflict between the United States and Russia.

The big picture in Syria is daunting indeed. It encompasses a region in the grips of state failure. A coherent Syria policy cannot be divorced from the volatile region of which it is a lynchpin; nor can it be divorced from grand strategy and geopolitics. What happens in Syria affects American relations with much of the world.

America’s strategic depth and deterrent power are tangible assets that have taken a beating as a result of Washington’s contradictory, halting, and passive response to the Arab uprisings. The United States postponed a rethink of its relationship with Saudi Arabia, corroding the most productive aspects of the partnership while remaining wedded to the most toxic. America’s Saudi plight is most bitterly apparent in Washington’s almost casual, and fantastically wrong-headed, decision to support Saudi Arabia’s criminally executed war in Yemen — as if in apology for America’s pursuit of the Iran nuclear deal over Saudi objections.

British Foreign Minister Boris Johnson reflected the growing understanding that Western inaction has persisted long past the breaking point when he told a U.K. parliamentary committee yesterday that the siege of Aleppo had dramatically changed public opinion. “We cannot let this go on forever,” Johnson said. “We cannot just see Aleppo pulverized in this way. We have to do something.” Reportedly, British defense officials are considering how to enforce a no-fly zone without getting into a shooting war with Russia and are also considering attacks on the Syrian military.

It might be true, as analysts and former Obama administration officials keep pointing out, that the existing policy has been driven by good intentions and that any shifts or tweaks are unlikely to save Syria from ruination. It might be true that there are no pat solutions to the Syria crisis.

But that’s misleading, only part of the story. When America changes course, so will other players, including Russia, Iran, and the government of Syria. A different style of intervention from the one America is pursuing now could save some lives, which is no small accomplishment. And finally, while it’s not only about America, (or about Syria), an escalation in Syria that is designed to send messages to American rivals and contain the strategic fallout could, if well executed, produce yields in surprising places, as America’s deterrent stock rises and a renewed belief in American activism and engagement restores the U.S. role as global ballast.

We are not all interventionists yet, no matter how shrill the protests from the camp that has tried to defend every twist and turn of Obama’s Middle East policy and now finds itself suddenly on the losing side of the debate. But it is not foolish to hope that somewhere between the destructive overreach of George W. Bush’s militaristic foreign policy and Barack Obama’s pursuit of balance and restraint, there exists a happier medium where America’s never-ending engagement with the most troubled parts of the world yields better results.

Syria’s Stalingrad

Photo: JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty Images

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

HOMS, Syria — More than four years of relentless shelling and shooting have ravaged beyond recognition this city, which once served as the symbolic capital of the revolution.

The buildings hang in tatters, concrete floors collapsed like sandcastles, twisted reinforced metal bars and window frames creaking in the wind like weather vanes. The only humans are occasional military guards, huddling in the foundations of stripped buildings. Deep trenches have been dug in thoroughfares to expose rebel tunnels. Everywhere the guts of buildings and homes face the street, their private contents slowly melting in the elements. Ten-foot weeds have erupted through the concrete.

As far as the government of Syria is concerned, the war in Homs is over. Rebel factions were defeated more than a year ago in the Old City, and the last holdouts, who carried on the revolt from the suburb of al-Waer, signed a cease-fire agreement this month. A few weeks before Christmas, busloads of fighters quit al-Waer for rebel-held villages to the north, under what the Syrian government and the United Nations hailed as abreakthrough cease-fire agreement to bring peace to one of the Syrian war’s most symbolic battlefields.

Gov. Talal al-Barazi, an energetic Assad-supporting Sunni, has been instrumental in pushing the cease-fires in Homs’s Old City and recently in al-Waer district. But almost none of the pro-uprising Sunnis who once filled its center have returned, and at times he seems to be presiding over a graveyard — an epic ruin destined to join Hiroshima, Dresden, and Stalingrad in the historical lexicon of siege and destruction.

By the end of a two-year siege of the Old City, the entire population of about 200,000 had fled, and more than 70 percent of the buildings in the area were destroyed. Today, according to the Syrian government, less than one-third of those who left have returned to the Homs area — but the ravaged city center is largely uninhabitable. Barazi said the cost of physically rebuilding the city would be enormous; without help from Russia, Iran, China, and other international donors, he said, full reconstruction would be impossible. Experts estimate it will cost upwards of $200 billion to rebuild across the entire country, or three times the country’s pre-war GDP.

And yet the Syrian government hopes to turn this shattered city into a symbol of its resurgent fortunes. Authorities showcase the reconstruction of Homs to spread a clear message: They intend to regain full control of the country. If they can tame Homs, a Sunni city where the majority of people actively embraced the revolt, they can do it anywhere.

There’s another more menacing message in the Homs settlement, however, as the neighborhoods that wholeheartedly sided with the revolution were entirely destroyed and have been left to collapse after the government’s victory. Almost no Sunnis have been allowed to return. Displaced supporters of the revolt from Homs understand that this is the regime’s second wave of punishment — they might never be allowed to go home.

This is the Homs model from the regime’s perspective: surround and besiege rebel-held areas until the price is so high that any surviving fighters surrender. The destruction left behind serves as a deterrent for others. Supporters of the government say that fear of a repeat of the ravaging of Homs is one major reason why militias around Damascus, like Zahran Alloush’s Army of Islam, have largely kept their indiscriminate shelling of the city center to a minimum.

The rebels, of course, take a different lesson: Assad will annihilate any opposition he can, unless the rebels fight hard and long enough to win, secure an enclave, or, at the very least, force the government to allow safe passage to another rebel-held area. Only force can extract concessions from the state.

A recent visit to Homs laid bare the deep divisions in the city and the near-impossibility of restoring what existed there before: a majority Sunni, but markedly mixed, community, more conservative and provincial than Damascus, but one that managed to successfully coexist despite profound communal differences.

As I stood in the middle of Khaldieh’s main square, in the center of Old Homs, I could recognize the bones of a familiar cityscape. Storefronts and five-story apartment blocks surrounded me. Avenues led in six directions from the roundabout.

I had seen this place before in video footage, when it played host to popular protests and later guerrilla fighting, and still later to a relentless barrage of Syrian government artillery intended to bludgeon all resistance. What remains today is an obliterated landscape that would be worthy of a dystopian sci-fi flick, if it weren’t so real.

The only sound, the ubiquitous sound, is the whistle of the wind, as loud as in the desert but incongruous in the heart of an ancient urban core.

My government minder fell silent after pointing out now-vanished landmarks. As we prepared to leave the square, she gestured dejectedly. “You can’t rebuild this,” she said.

The desolation continued for blocks in every direction, only abating up the hill toward Hamidiyeh, a mixed neighborhood to which a few dozen families, some Sunni, some Christian, have returned.

A bicycle parked outside a bombed schoolhouse is the only sign that you have reached the re-inhabited part of Khaldieh. Two boys kicked a soccer ball in a narrow courtyard delineated by rubble and broken walls. They pointed us in the direction of Maamoun Street, which begins at a grand Ottoman-era house, with a fountain and interior courtyard. One window had been refashioned into a sniper’s nest, a car frame shoved into the window.

Abdulatif Tawfik al-Attar, 64, is one of the few Sunnis to have returned to the Old City, the historic district near the center of Homs. Perhaps he was trusted by the government because of his outspoken criticism of the rebels, whom he said “came and destroyed everything.”

Now Attar is slowly rebuilding his shattered life. His wife and daughter live in a rented apartment on the outskirts of Homs while he restores their home to livable condition, room by room. Before the war, he worked as a mechanic at a government refinery. Now he repairs bicycles in his entryway.

He cherishes what he considers his ample blessings. All three of his children survived the war, he still draws a government salary, and the walls of his home are still standing. “For me, the situation could be far worse,” he said.

A chatty man who dropped out of high school for his first job, Attar finds it difficult to sit still. He’s ready to brew tea on a portable burner hooked to a car battery or prepare a water pipe for guests who like to smoke. But in the Old City, hardly anybody drops by to visit, except for a middle-aged neighbor also painstaking reconstructing his house.

“It is lonely here sometimes,” Attar admitted. He apologized for the spartan conditions in his home. His son invited the family to join him in Saudi Arabia, but Attar said he wasn’t interested. “I love my country,” he said. “I don’t want to live anywhere else.”

Quietly, he began to cry. “We have lost a lot in Syria, especially in Homs,” he said. “We didn’t used to have women begging outside the mosques.”

After a moment he said, “Homs will be back.”

The local Ministry of Information official charged with supervising journalists in Homs, an Alawite who also hails from the city, began to cry as well. One of her sons died fighting for the government in Daraa; her husband and remaining two sons are still on active duty in the military.

“We have lost so much,” she agreed, fingering the gold pendant she wears around her neck engraved with her slain son’s portrait. “Even our own children.”

Attar squeezed the official’s arm to comfort her. “Don’t be sad,” he said. “No one dies before it is written. People run away from the war to escape death, and they die in the sea. People went on the hajj, and 800 died in a stampede.”

One day the war in the rest of Syria will come to an end, they said, as it has in Homs — but if Syria is to recover, it will have to transcend the sectarian divisions exacerbated by the war.

“Those men who have hurt us have hurt themselves, too,” Attar said. “God knows what everyone has done. Human beings make mistakes.”

The minder quoted a saying she attributed to former President Hafez al-Assad, father of Syria’s current leader: “Religion is for God, and the nation is for everyone.”

“That’s how we grew up,” she said. “If you live in a country with government, land, home, you want to forgive so that you don’t lose everything.”

These pro-government Homs residents expressed nostalgia for a version of coexistence that worked for them. But the Assad government so far has offered rebels few options beyond submission and surrender — nothing that looks like increased rights for the majority of citizens. Homs Gov. Barazi, for instance, argues that as the city limps back to life, people will return, including Sunnis who might have sympathized with the uprising.

“Between Christmas and New Year’s, you will see a new Old Homs,” Barazi said, in an interview on the sidelines of a conference in Damascus about how to reboot the Syrian economy. “Once the shops open, you will see the things go back to life.”

He said the occasional car bomb or shell that strikes Homs didn’t threaten the city’s overall security. “It’s much safer in Homs than in Damascus,” he said.

Many government supporters don’t like the cease-fires that Barazi has championed, especially because they allow some fighters to flee and continue fighting elsewhere. The recent deal in al-Waer allows those rebels who surrender their heavy weapons to remain and govern their neighborhood. Activists suspect the government might round up rebels and dissidents later.

His strategy is to start with quick anchor projects in the worst-hit parts of Old Homs: rebuilding schools, historic places of worship like the Notre Dame de la Ceinture Church and the Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque, and now 400 stalls in the old marketplace. He is counting on Russia, China, and Iran to foot the bill of what will be an enormously expensive project. He estimates that maybe one-third of the displaced residents from Old Homs have returned to the city, if not yet to their original homes.

Several Christian parochial schools reopened this fall in the Hamidiyeh quarter of Old Homs. About 200 students came to the first day of school, out of a pre-war enrollment of 4,000 in the neighborhood, according to Father Antonios, a priest who helps run the Ghassanieh School. At pickup time, parents said they still didn’t feel safe in their old neighborhood. “We’re doing a lot of work to reassure people,” the priest said.

The government’s strategy overlooks the daunting, practical obstacles to resuscitating a city as thoroughly ravaged as Homs. It also ignores the bitter feelings of the people who supported the revolution and will never reconcile themselves to Assad’s rule.

Homs might yet be a model, but perhaps not the one intended by Syrian government officials — it might end up as this war’s lasting symbol of ethnic cleansing or urban siege war without restraint. The government’s showcase plan doesn’t make room for the legions of Homs natives who rose up demanding rights from a government that systematically tortures its citizens and allows them no say over how they’re governed. Anti-government activists also say that Sunnis are systematically denied permission to return to the Old City because authorities suspect that a reconstituted Homs will continue to act as a bastion of resistance.

“People still support the revolution,” said a retired resident, who never left Homs throughout the war. The resident spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of government retribution against his family members.

Homs proved the futility of expecting the Syrian government to reform, this resident said. He lamented how it responded to peaceful protests with lethal force and indiscriminate arrests and torture.

“For six months, no one carried so much as a knife. When the regime began killing them, they defended themselves,” the resident said. “I’m so sad about Syria. I stopped thinking about the future a long time ago. I live one day at a time.”

Periodically during the siege of al-Waer district, this resident smuggled in food and meat to civilians. With like-minded friends, the resident cheered advances of the rebel Free Syrian Army on battlefronts around the country. Today, the resident said, depression has set in, with the government precariously in charge of a city that once felt like the first liberated place in Syria.

“I feel like I will explode,” the resident said. “All these people died, in every possible way, for what? I can’t believe that everything will finish and Bashar al-Assad will still be president. I would rather die.”

Slow death of Damascus

Photo: SAMEER AL-DOUMY/AFP/Getty Images

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

DAMASCUS, Syria — Until civil war broke out in 2011, Iman enjoyed a comfortable life in Mezze, the center of middle-class Damascus and a popular neighborhood for Syrian government employees. The 39-year-old devoted herself to her two sons, never dreaming her family could ever slip out of the comfort that, after all, was an explicit promise of President Bashar al-Assad’s Baathist state.

Today, the endless grind of war has reduced Iman’s life to a constant state of anxiety. She keeps her sons in hiding, afraid they’ll be drafted by a government hungry for conscript soldiers or simply grabbed by militiamen, who have been known to arbitrarily arrest innocent civilians and hold them for ransom or even forget them in detention. Her psychologist husband quit his practice because he made better money driving a taxi — but then the war made the roads too deadly, and now he says he hasn’t left the house in months. Iman, meanwhile, cleans houses for $3 day — not enough to buy food — and begs her casual employers to pay her utility bills.

Sitting at a café popular with government supporters and members of the security service, she spoke openly about her fears and her desperation to find a path to Europe.

“I live in fear for my sons every day, that they will be drafted or disappeared. There is no solution for this crisis,” Iman said. She placed her tongue against her front teeth and made a long, low whistle. “It will be long, long, long.”

Iman’s plight is shared by thousands of Syrians living in today’s Damascus. Their stories all point to a central quandary facing Assad: How long can his beleaguered government keep its supporters engaged in the fight, as Syria struggles with colossal human losses and economic deprivation?

Few supporters of the government are switching sides to the opposition these days, but many are simply exhausted by the immense toll exacted by the war. Half the country’s people have been pushed from their original homes. The infrastructure is creaking. Even some supporters of Assad say they feel that government-held Syria is hollowing out, running on fumes.

In private, people discuss the point at which they’ll give up. One says they would flee if the road from Damascus to the coast were permanently cut. Another says the breaking point would come if the Islamic State entered central Damascus. For the Assad government, all this worry is driving the Russian- and Iranian-backed campaign initiated last month to save Syria’s urban heartland — a narrow belt of cities stretching from Damascus to the coast — even as the hinterland slips away from the government’s grasp.

The answer to whether Assad’s forces can keep that heartland lies with Syrians like Iman, who have chosen to remain in government-controlled areas and consider themselves neither rebel sympathizers nor government boosters. Iman is a Sunni who wears a headscarf, and some of her relatives are in prison — enough to make Iman herself suspect in these days of heightened sectarianism.

“My neighbors all work for the government, and as long as we walk straight, they leave us alone,” Iman said. “Unless someone writes a report about us.”

Her gripe, however, isn’t with the state or its leaders. She had no intention of leaving until the Syrian currency collapsed, along with her husband’s livelihood.

She dreams of Germany’s free medical care, which she hopes can treat her older son’s eye problems and younger son’s asthma. But she’s terrified that before she can amass the $6,000 she thinks it would cost to smuggle her family to Europe, her sons will be swallowed up by the Syrian military. With their health problems, she’s convinced they wouldn’t survive long in uniform.

Life during wartime

Over the course of a recent 10-day visit, Damascus residents said they feel less embattled than they did a year ago, but the war is still an inescapable reality of everyday life. Every night, dozens of mortars still land in the city center, sending wounded and sometimes dead civilians to Damascus General Hospital. From the city’s still-busy cafés, clients can hear the thuds of outgoing government guns and the rolling explosions of the barrel bombs dropped on the rebel-held suburb of Daraya.

Army and militia checkpoints litter the city. In some central areas, cars are stopped and searched every two blocks. Still, rebels manage to smuggle car bombs into the city center. According to residents, explosions occur every two or three weeks, but are rarely reported in the state media.

Workplaces across the country have emptied out over the summer, as Syrians with a few thousand dollars to spare risked the trip to Europe via Turkey and a boat ride to Greece, taking advantage of a newly permissive Syrian government policy to issue passports quickly and without question.

Employees in government offices, international aid organizations, and private Syrian corporations estimated that anywhere between 20 and 50 percent of their coworkers left the country this summer.

“The government doesn’t care if people leave. It can’t stop them,” one middle-class Syrian, who has chosen so far to remain in Damascus, said of the exodus. “The war seems like it will go on forever. People see no future for their children. The only people who are staying are the ones who have it really good here or the ones who aren’t able to leave.”

Over the last year, the Syrian military has suffered a major manpower shortage, which Assad acknowledged this summer in a rare, frank public assessment of his vulnerabilities. Meanwhile, Syria’s currency tumbled to one-sixth of its prewar value, causing an economic crisis for all but the wealthiest citizens. Rebels have made steady territorial gains throughout 2015, until the recent Russian military intervention threatened to turn momentum in the government’s favor.

Yet for all the danger signs, Assad’s government tries to project confidence. It has lost key territory in the north and east, but it still controls most of the important urban centers from Damascus to the coast, where anywhere from half to 80 percent of the population lives. Members of all of Syria’s ethnic and sectarian communities, including many from the Sunni Arab majority, continue to support the government.

The government showcases its readiness at Damascus General Hospital, whose emergency room treats the capital’s civilian casualties. Despite nationwide shortages and difficulties created by Western sanctions, hospital administrator Dr. Khaled Mansour said the hospital still strives to keep six months of supplies on hand.

“We are prepared to continue serving the population even in the case of a siege,” Mansour said. It has been tough to keep sophisticated machinery like scanners working, he said, and to maintain reserves of diesel and water. Imported medicines are more expensive after the currency collapse, and many pharmaceutical factories are located in areas now under rebel control.

It’s also hard to keep doctors from emigrating. According to Mansour, rebels have kidnapped some medical professionals and forced them into service, and Syria’s well-trained doctors find it relatively easy to emigrate. About 200 out of 650 doctors left the country over the summer, Mansour said, while adding that the hospital had more than enough “spare capacity.”

The brain drain, however, is evident in the examining rooms.

“We used to have the best doctors in Syria,” one patient said wistfully. Now, he said, quality was down; during a recent medical appointment, two young doctors had consulted Google on a smartphone to decide which medicine to prescribe.

Boomtown on the coast

If Damascus can feel like a city under siege, the Syrian coast resembles a booming war economy. Millions of Syrians fled the fighting early in the war and relocated to the safer coastal cities of Tartus and Latakia. The coastal cities are considered strongholds of the Alawite minority, of which the Assads are members. But they have sizable populations of Sunnis and other groups, and tensions have grown as displaced people, mainly Sunnis, have fled to the coast from war-torn parts of the country.

The displaced have driven up rents and strained the infrastructure, but they’ve also brought money, and many have reestablished their old businesses. The Ministry of Social Affairs has created dozens of new positions to employ displaced people. Down the street, Mohammed al-Heeb, a pastry shop owner originally from Aleppo, has created 30 extra jobs for displaced people, mostly make-work positions to help families in need. Despite the charity, he’s still turning a profit.

The fight has become an integral part of daily life, directly affecting almost every family from every type of background. Throughout the coast, photographs of the war’s casualties adorn every block. Each neighborhood has a wall of martyrs, some of them featuring hundreds of dead — part of an effort to build a martyrdom culture not unlike that which sustains loyalists of Iran’s ayatollahs and Lebanon’s Hezbollah, both of which provide key support to the Syrian government.

The government avidly pursues draft dodgers and, at the same time, has made a special effort to burnish the cultural cachet of the families making sacrifices to defend Assad’s state.

The sanctification of martyrs

In the hills above Tartus, the provincial governor in early October unveiled an art fair entitled “Tartus: Mother of Martyrs.” For the exposition, the governor commissioned 30 sculptors to build marble tributes to Syria’s fallen. Most of them included literal representations of mothers, along with local motifs encouraged by the governor, like Phoenician boats and a phoenix rising from ashes.

Hundreds of war-wounded and relatives of soldiers who died in the conflict gathered in the hilltop village of Naqib for the unveiling of the statues. Parents wept as a local official read the names of the fallen — nearly 180 just from the village and its environs, an area with a population of about 80,000 people, according to the mayor.

“This is our destiny,” said Ahmed Bilal, an Alawite cleric who was circulating in a shiny white robe and chatting with the assembled families. A long line of fighters predating the establishment of modern Syria had resisted foreign invaders, he said, and gave inspiration to today’s soldiers.

“Even if we lose one-third of our young men, we will still have the rest to live,” Bilal said. “They died so that the others should have life.”

Saada Shakouf, one of the bereaved mothers, sharpened her sense of Syrian identity after her son died fighting rebel forces in March in the battle of the northern town of Jisr al-Shughour. The opposition victory, which was accomplished by a coalition that included the al Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front as well as U.S.-backed, Free Syrian Army-linked groups, created a sense of panic in government circles. From Jisr al-Shughour, the rebels had a gateway to the coast, allowing them to directly threaten strongholds like Latakia.

Shakouf’s son, Nabil, was 23 years old when he died along with his entire unit. He had been “stop-lossed,” a procedure for extending a soldier’s service beyond his or her time of enlistment, and was in his fourth year of military service. According to his mother, Nabil and his companions were burned to death in barrels. She didn’t know if they had hidden there — or if the rebels placed them in the barrels and set them on fire as a grisly form of execution.

Government forces are fighting for a model of coexistence and tolerance that is vanishing from the Arab world, Shakouf said. She had lost her enthusiasm for the pan-Arab cause that had once been so central to Syria’s political identity.

“We used to say the Arab nation was one, and we supported the rest of the Arabs against Israel. Where are those Arabs now? They are attacking us; they are attacking other Arabs,” Shakouf said with bitterness. “We don’t believe in the Arab nation anymore.”

An official from the Ministry of Information who was monitoring the interview interjected: “You can’t say that!”

Shakouf, however, refused to back down.

“We are only Syrians,” she insisted. “Syria can protect itself alone. We don’t need anybody to help us.”

Times could get much leaner than they are now in Tartus, and families like Shakouf’s will be called upon to continue to support the fight. Strained by dwindling resources, she said, the resolve of Syrian government loyalists would only grow. She promised that her surviving daughters and 15-year-old son said they would join the military if called.

“We fought the Ottoman Turks for 400 years,” Shakouf said. “There is no way we will fall. We have been fighting five years for our existence, and we will not lose.”

Cheering Russia’s Airstrikes in Assad’s Heartland

Emergency responders rush following a reported barrel bomb attack by government forces in the Al-Muasalat area in the northern Syrian city of Aleppo on November 6, 2014. PHOTO: TAMER AL-HALABI/AFP/Getty Images)

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

QARDAHA, Syria — The sonic boom of a fighter jet momentarily cut short the conversations at the hilltop mausoleum of former President Hafez al-Assad. The engineer in charge of enhancements to the manicured park and shiny marble shrine to the founder of Syria’s ruling dynasty broke out into a wide grin.

“The Russians!” said one visitor.

“The plane is Russian, but I bet the pilot is Syrian!” he said with a laugh.

Syria’s coastal cities were buzzing this week with anticipation that a muscular Russian contingent would alter the momentum of a war stretching into its fifth year, giving backers of the regime a catalytic push to victory.

Qardaha is the former president’s birthplace as well as his final resting place, and it symbolizes a Syrian regime whose Baathist and Arab nationalist ideology is inextricably intertwined with the ruling Assad family.

Syria’s leadership has staked its future on preserving its prewar ruling constituency. In almost every conversation here, fighters opposed to the government were called “terrorists” rather than rebels, and the civil war that has killed more than 200,000 people and has displaced 12 million others is still called “the crisis.”

The war’s grinding toll hasn’t dampened the optimistic rhetoric of government officials and supporters, like the shrine supervisor Maan Ibrahim.

With the help of Russian President Vladimir Putin and other allies, he promised, Syria would prevail against its enemies. “War has been raging for five years,” Ibrahim said. “All these terrorists will meet their end here and now.”

Analysts have been trying all week to untangle the thicket of overlapping interests driving the Kremlin’s escalation in Syria. On the ground in the part of Syria still tightly under the control of President Bashar al-Assad’s government, however, the strategy was far clearer than would appear from the speeches and statements emanating from world capitals. Scores of interviews with regime supporters and local officials in the Alawite heartland could be summed up in a simple plan: no quarter, no compromise.

Whether it’s likely to succeed or not, the regime has persuaded its own constituents to support Assad’s blueprint, regardless of any ambivalence they might express in private.

The plain is straightforward: consolidate Damascus’s control over the axis that runs from the capital through the contested cities of Homs and Hama and to the coastal strongholds of Tartus and Latakia — an area that represents the bulk of Syria’s prewar population. Eliminate all armed rebels from that heartland, and then reconquer the economically critical city of Aleppo along with farther-flung districts that have fallen out of the government’s control.

Westerners have parsed the distinctions among the Islamic State, jihadis like the al Qaeda affiliate al-Nusra Front, Ahrar al-Sham, and the U.S. backed Free Syrian Army. Supporters of the regime, on the other hand, view all armed rebels as sectarian terrorists determined to wipe out or marginalize Syria’s religious minorities and therefore as equally deserving of whatever firepower Assad or his foreign allies are able to muster against them.

“The ones who accept President Assad’s amnesty can come back and be part of Syria,” said a pro-regime fighter relaxing at a cafe in the port city of Tartus. “The other traitors will stay abroad or fight until we kill them. They cannot return.”

The fighter, like many other government supporters, expressed a hope that with the new Russian engagement, the long conflict would come to an end quickly. “We’ll take back all the land in a year,” the fighter said. “After that we’ll only have to worry about sleeper cells.”

Syrian officials believe that the international tide is turning in their favor and that the question is no longer in what condition the regime will survive — but rather how long will it take for the regime to win outright.

That new confidence was on display as the governor of Tartus province received visitors in his ornately re-created Ottoman-style office, while smoking cigarettes and sipping an orange-flavored soft drink. An aide in the waiting room coyly avoided direct praise for the Russian involvement until he found an updated story on his smartphone from the state-run Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA).

“It’s confirmed on SANA!” he said with excitement, and read aloud a long account of Russia’s first airstrikes.

The governor, Safwan Abu Saada, said it was only natural to feel optimistic. He had been in charge of the northern province of Idlib until a year ago, when the government’s losses forced him to move.

“Syria is like a phoenix rising from the ashes,” he said.“We welcome the help of friendly countries, working with our invitation and under international law. I’m sure I will be visiting Idlib again soon.”

Answers to the many questions about how such a major shift would come about, however, still remain unclear. Assad’s regime already has been throwing all its resources into the conflict, with generous military and financial support from Iran and Russia. The new Russian intervention — fighter planes, anti-aircraft systems, and advisors — comes after a six-month period in which the regime lost ground in Idlib province, dangerously close to towns such as Qardaha and the strategic heart of the regime, where public support runs strongest.

Latakia, the largest of the coastal cities, embodies many of the challenges to the government’s strategy. The population of the city and its suburbs has nearly doubled over the course of the conflict to around 3 million people, according to Syrian officials. Displaced people from Aleppo and other provinces have flooded into the city, straining its infrastructure but also spurring an economic boom.

Almost every block is festooned with photographs of martyrs from the military or paramilitary units. Anxiety in Latakia spiked this spring when neighboring Idlib province fell to a rebel advance of a new coalition called the Army of Conquest, spearheaded by a coalition of jihadis including al-Nusra Front, fighting alongside Free Syrian Army units.

Pushing the rebels farther away from the coast is a much higher priority for regime supporters here in the Alawite heartland than the eradication of Islamic State strongholds in places like the eastern province of Deir ez-Zor, which lies hundreds of miles inland.

An off-duty army officer, recovering from an end-of-week lunch, said that Syria’s fundamentalist enemies “would pay for every drop of blood they had spilled, and every drop of whiskey.”

But he was less sanguine than some of his peers in his assessment of the Russians. “The Russians are part of the process, with their airstrikes, but it’s a little part,” said the officer. “In the end it is Syrians who are on the ground fighting.”

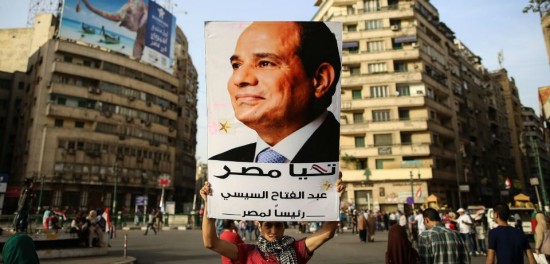

Egypt’s Sisi Is Getting Pretty Good … at Being a Dictator

Photo credit: MOHAMED EL-SHAHED/AFP/Getty Images

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

The outrageous death sentences in Egypt over the weekend, and the muted reaction from Western governments, suggest that President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has cemented a ruling coalition that will propel him out of a transitional phase into a long-term project of power consolidation.

Lost amid the court ruling against more than 100 defendants — which include academics and senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood, even Egypt’s sole elected civilian president, Mohamed Morsi — is the mounting evidence that Sisi has cobbled together a workable formula for ruling Egypt. This formula might be doomed in the long run, but the long run can be very far off indeed.

Today’s governing agenda in Egypt centers around three things: a crackdown on “terror” and dissent, maintaining a steady flow of cash from the Sunni monarchies of the Gulf, and modest economic reforms that at a minimum give the impression of vision and positive momentum.

The government’s “war on terror” will resonate with Egyptians for quite some time. Jihadi attacks have proliferated since Morsi was deposed in July 2013; one fact sheet released by the government last year documented more than 700 people killed in the attacks. There have been dozens since, mostly targeting security forces and government facilities.

The public is repulsed by the bomb attacks on the police, army, and other government branches. Even most of the Muslim Brotherhood supporters of the deposed Morsi also condemn the insurgency and its terrorist tactics. As a unifying ideology for the Egyptian state, a war on terror might not suffice — but it will go a long way to mobilize what might be otherwise tepid support for Sisi and the military.

In prosecuting its war on terror, Egypt has lumped the Muslim Brotherhood together with the jihadi Ansar Beit al-Maqdis — equating dissent in the vernacular of political Islam with bombings and assassinations. “The Muslim Brotherhood is the parent organization of extreme ideology,” Sisi told the Washington Post in March. “They are the godfather of all terrorist organizations. They spread it all over the world.”

Perhaps Sisi is motivated by a sincere belief that the entire Islamist current is collectively responsible for the recent attacks, or perhaps he’s made a cynical calculation that the spate of violence offers an opportunity to eliminate the mainstream Islamist opposition under the cover of fighting an insurgency.

The battle against Islamists has given Sisi some legitimacy — but it isn’t what brought him to power. For that he counted on Gulf money, an initial precondition of the coup that toppled Morsi. As we’ve heard in great detail on leaked recordings from the office of Sisi’s chief of staff, the president made clear that he expected the billions to flow unabated from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies: “Man, they have money like rice,” a man who sounds like Sisi famously says in one of the leaks.

This might sound like thuggish extortion, but it’s also shrewd politics. Sisi recognizes that the Gulf can afford to underwrite Egypt, and that it’s willing to indefinitely pay $10 billion or more a year for a dependable ally in Cairo. Egypt struggles to import enough fuel and food staples to keep the country functioning and the poor quiescent; without Gulf money, the summertime power outages would likely turn into long-term blackouts and electricity rationing.

Egypt’s rulers have historically feared a “revolution of the hungry” if the circumstances decline for the nation’s many poor.

Economic reform, the last piece of the formula, is trickier. It’s become clear that Sisi’s autocratic ways and narrow, nepotistic circle of military advisors will preclude creative governance. But while significant reform is off the table, piecemeal improvements to the subsidy system could serve Sisi adequately for the medium-term. Meanwhile, theatrical flourishes like the $45-billion new capital planned for the desert outside of Cairo — a boondoggle for Emirati construction conglomerates which will probably never be built — and massive proposed public housing, irrigation, and road works projects give the impression of a nation on the move.

If even a small fraction of these projects materialize, Sisi will cement deep support in some quarters. Wealthy business owners and the small but politically influential middle class have both reliably remained in Sisi’s corner, and could benefit from infrastructure development. The military will also play a major role in any large-scale construction projects and, if shrewdly distributed, new housing or other perks could neutralize some of the few potential oases of organized political opposition, such as factory workers in the cities of the Suez Canal zone and the Nile Delta.

The medium-term stability of Sisi’s regime, however, may lead to more trouble for Egypt down the road. His repressive policies will not cure the country’s many ills, and are guaranteed to drive Egypt into even worse shape that it was when it rose up against Hosni Mubarak in January 2011. Recent events underscore Sisi’s paranoid style, punctuated over the weekend by banning soccer fan clubs known as Ultras and sentencing exiled political science professor Emad Shahin to death. As Shahin put it in a statement, the show trials are a centerpiece of Sisi’s effort “to reconstitute the security state and intimidate all opponents.”

The pattern of prosecutions fits that argument. If the government casts its net wide enough, it won’t have to worry about student union protests or critical university professors, because the majority of Egyptians will be frightened into silence.

Sisi’s paranoid style appears to be the product of a coherent view among Egypt’s fractious security services, which are showing a unity of purpose in carrying out the campaign against all political dissent. The military, police, intelligence agencies, and courts are pulling together to carry out the government’s political vision — an impressive bureaucratic achievement, but one that bodes poorly for democratic reform.

The downsides of the new dictatorship’s governing approach will be toxic for Egypt over the long haul. Securing the cooperation of a balkanized bureaucracy is not the same as controlling it: Sisi has the courts in lockstep on his side, but at the expense of their reputation. The courts have clearly abetted military rule, disbanding the elected parliament on flimsy pretexts, barring popular presidential candidates, and certifying election laws that served the military’s aims.

As a result of these machinations, no one will be able to take the judiciary seriously as a branch of government — and a future ruler, even an unelected autocrat, who wants to restore some semblance of the rule of law will face a daunting rebuilding job. The situation only deteriorated further today, with the appointment of Ahmed el-Zend as justice minister: The head of the influential “Judge’s Club” famously told a television show that judges “are masters in our homeland. Everyone else are slaves.”

The army, which paved Sisi’s path to power, remains the president’s only native constituency. But there’s no evidence to suggest that in a crisis — say, an economic collapse or a widespread popular uprising — Egypt’s generals would sacrifice their own institutional privileges to protect Sisi.

Even authoritarian rulers must play politics to retain power, pacifying the key organizations and constituencies that support them. Under the former dictator Hosni Mubarak, the military had to compete against the police, the intelligence services, and the circle of business moguls around the ruling family for its perks. Today, the military possesses unchecked power, which is likely to lead to greater corruption, unaccountability, and serial failures to accomplish the basic bread-and-butter business of the state.

This incompetence will negatively affect the very war on terror upon which Sisi is building his legitimacy. Jihadis are openly operating out of the Sinai, but according to the few independent reports that come out of the peninsula, poorly trained soldiers have employed scorched-earth tactics in retaliation, bombing towns and arresting random men while actual jihadis escape. Convicting and trying men for crimes theyprobably didn’t commit — as appeared to occur over the weekend in aballyhooed terror trial — won’t end the destabilizing domestic insurgency either.

Sisi also faces other long-term threats that are not solely of his making. These include an untenable national balance sheet, subsidies too expensive to maintain and too crucial to eliminate without massive social dislocation, growing unemployment, and inadequate water for agriculture under current usage practices.

Ultimately, any economic reform will depend on foreign pressure — a formula that didn’t work when the United States was the primary donor. Perhaps financial advisers from the United Arab Emirates will have better luck as they try to implement better practices in the ministries and government offices that will absorbed upward of $32 billion from the Gulf monarchies ever since Sisi’s coup. If those massive sums can’t buy meaningful political influence or instill sound economic practices, no amount of foreign money will.

The new regime is clearly unable to resolve these challenges, but history suggests that mismanagement can continue for a long time. Indeed, perhaps the greatest threat to Egypt is that Sisi simply muddles through. There are surely fissures within the regime, but he doesn’t need a monolithic ruling elite: He needs just enough power to stay in charge, and enough international support to ignore the outrage of Egyptians who want civil rights, political freedom, and genuine economic development.

Lebanon’s ‘Democracy of the Gun’

Munir Makdah, Fatah boss of the camp and commander of the Joint Security Committee. Photo: Thanassis Cambanis

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

AIN EL HILWEH, Lebanon — The gunmen who control this tiny, cramped Palestinian refugee camp in south Lebanon are uncharacteristically eager to please. Hardened militants scurry to meetings with political rivals, and speak with newfound candor to journalists about past unsuccessful efforts to overcome a history of deadly feuds in the camp.

For decades, the coveted slot of camp boss has gone to the man able to deploy the most shooters and force Ain el Hilweh’s unruly clans and factions to fall in line. Today, however, an unlikely new order prevails: Bitter rivals have forged an unprecedented level of cooperation to police their sometimes-anarchic camp, forcing the most violent jihadists to lay low, and even turning over Palestinian suspects to the Lebanese Army, an act that just a few years ago would have been considered an unpardonable treason. Strongman Munir Makdah, a member of the Fatah movement, presides over a special council of 17 militia leaders — including some borderline jihadists — who must approve the most sensitive moves.

“It’s very important: This is the first time we’ve done anything like this,” Makdah said during a recent visit to his headquarters, nestled in Ain el Hilweh’s claustrophobic horizon of apartment blocs. “I call it the democracy of the gun. We tell our brothers when they visit that they can do the same thing in Palestine.”

Since its establishment in 1948, Ain el Hilweh has been a byword for militancy — a haven for fugitives and a bête noir (at different times) to the Lebanese government, the Israeli military, even the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

An estimated 100,000 people live in the camp, which is rimmed by walls, barbed wire, and army checkpoints. Under a convoluted agreement, Lebanese soldiers search the cars going in and out, but don’t enter the camp itself, leaving policing inside to the Palestinian factions.

The experiment underway in this camp represents a rare instance of cooperation and pragmatism in a region where fragmentation and infighting is the norm. Much more is at stake than simply the stability of an overpopulated square kilometer: There is a widespread fear that if the Islamic State, or jihadists sympathetic to the group, ever gained a foothold in Lebanon, it will be in a place like Ain el Hilweh — where residents are poor, politically disenfranchised, and ineffectively policed.

The agreement in Ain el Hilweh presents significant potential upside, too, in a region currently short of examples of political progress. The camp is home to actors who can impact flashpoints all over the region: It could contain the seeds of reconciliation between Hamas and Fatah in Gaza and the West Bank, while authorities everywhere might look it as a model for a successful initiative to curb jihadists.

“Syria’s war was like a storm coming to us,” Makdah said. “Everyone was worried about the camps. We reflect society.”

When it comes to security, senior Hamas officials in Ain el Hilweh amiably take orders from Makdah. At the camp’s Hamas office, a visiting Fatah official refilled the Hamas chief’s coffee cup as the Hamas official gave his unvarnished assessment of the regional security situation. “Honestly, we Palestinians are in a weak position,” said the official, Abu Ahmed Fadel.

Fadel said it took the factions much too long to learn the lesson of the crisis in the Nahr el Bared refugee camp in north Lebanon in 2007, when jihadists battled the Lebanese Army. That fight destroyed the entire camp and left 27,000 residents homeless. Ever since then, Fadel said, Lebanese leaders suggested that the Palestinians set aside their internal differences and form a united front. It took what Fadel called “the fires in Syria” to finally push the sides to agree.

“Compared to what’s happening around us, we’re a stable river,” said Khalid al-Shayeb, the Fatah deputy who’s in charge of the patrols in Ain el Hilweh and the neighboring Mieh Mieh camp. “We managed to neutralize the threats from Palestinians much more effectively than the Lebanese Army has managed to neutralize the threats from the rest of Lebanon.”

There’s no sign here of the discord that forced a bitter break between Hamas and its long-time patrons in Damascus, or the blood feud between Hamas and Fatah, or between Hamas and the more extreme religious factions like Islamic Jihad and Ansar Allah. One fear has managed to outweigh all that acrimony: the dread of an encroachment by the Islamic State, whose entry into the camp could provoke outsiders to destroy it and cost the grand old factions everything.

“People should be united because there is a threat to everybody,” said Ali Baraka, a senior Hamas official based in Beirut.

That’s not to say that the camp’s residents have entirely stayed out of the Syrian war. Some reports say that one of Makdah’s own sons snuck into Syria to join the jihadists. Makdah has figures of his own: precisely 52 Palestinians from all the camps in Lebanon, he says, have been tracked joining the Syrian jihadists.

The impact of the war is felt everywhere in Ain el Hilweh. A human flood of refugees has entered over the past several years, filling the impossibly crowded camp to its breaking point. According to Makdah, at least 20,000 newcomers moved to the camp since 2011, when war broke out in Syria. Officials have struggled to maintain the camp’s fragile water supply and say they can’t provide adequate education, housing, and health care to the camp’s residents. Until last week, Makdah said, he had turned over his offices to refugees. Now that they’ve found better dwellings, he’s moved back in.

A murder in April tested Makdah’s efforts to construct a new order in the camp. A Lebanese supporter of Hezbollah named Marwan Issa was dragged into Ain el Hilweh and murdered. According to Palestinian security officials, Issa was a member of a Hezbollah auxiliary militia called the Resistance Brigades, and his suspected killers were known arms dealers. They believe the murder was related to a weapons deal gone awry. Two suspects were quickly apprehended. Leaders of the 17 factions called an emergency meeting to vote on whether to hand them over to the Lebanese authorities.

“Usually the Islamic factions object,” said Bilal Selwan Aboul Nour, the camp security officer in charge of liaising with the Lebanese security establishment. “In this case, it was different. The victim was Lebanese. And if we didn’t cooperate, it could bring trouble on the entire camp.”

Aboul Nour immediately delivered the captives himself to the Lebanese Army barracks up the road.

A third suspect in the murder remains at large in the camp, however, illustrating the limits of this new cooperative order. That suspect is under the protection of Jund el-Sham, a jihadist faction, in the Taamir area of the camp. “We can’t use force,” Aboul Nour said. “He’s in an area outside our control.”

Hezbollah and the Lebanese government have been patient and understanding, according to the Palestinians, although Hezbollah called the killing a “stab in the back of the Lebanese resistance.”

It was the Islamic State’s infiltration of the Palestinian camp of Yarmouk in Damascus that motivated the dithering Palestinian factions to unite last summer. At the time, the already unraveling region was experiencing extra strain: The Islamic State had seized much of northern Iraq and declared a caliphate, and had seized control of some entrances to Yarmouk and assassinated Palestinian operatives, according to Baraka. Senior officials from Fatah, Hamas, and the Lebanese government quickly agreed that if the Islamic State could win followers in Yarmouk, it could easily do the same in Lebanese camps.

Since September, the Palestinian Joint Security Committee has doubled the number of camp police in Ain el Hilweh from 200 to 400. Fatah supplies the top commanders and foots 70 percent of the cost of the committee, and Hamas provides the rest. The officers are mostly familiar faces in the camp, some of them veteran fighters in their fifties. Now they wear red armbands that identify themselves as Joint Security Committee fighters. Makdah has not only brought together Fatah and Hamas, he has also convinced jihadists and secular Marxists to police the camp in joint patrols — a success that eluded generations of Arab leaders before him.

Most of the fighters still stay close to their factions: In the headquarters, Fatah old-timers cluster around the small fountain full of goldfish. Outside, Ansar Allah’s fighters — identifiable by their long Salafi-style beards — politely decline to talk to reporters. Near the hospital, the clean-shaven leftists of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine shun the uniform altogether; their unit commander, Ali Rashid, wears blue jeans and a brown leather jacket. The groups sometimes organize joint patrols, and the major checkpoints include fighters from all the factions.

It was especially difficult for secular leftists to join forces with Islamist jihadists, Rashid said.

“We agreed that we would cut off any hand that tries to mess with security in the camp,” Rashid said. “We cannot tolerate even the smallest action from any takfiri [extremist] who enters here.”

So far, he said, the extremists in the camp have obeyed the new order. They might shelter fugitives — but so long as the fugitives are in the camp they refrain from any active role in militant operations.

Makdah says the camp really needs 1,000 police officers. In March, he extended his writ to the nearby camp of Mieh Mieh. If the experiment continues to succeed, Palestinian and Lebanese security officials said they hope to spread the experiment to all the Palestinian refugee camps in the country.

Ain el Hilweh’s unique circumstances make it an unlikely template for other places: It’s a hyper-politicized area whose claustrophobic living conditions make the Gaza Strip appear positively suburban by comparison. But sudden and intense collaboration between militants of secular, Marxist, Islamist and jihadist pedigrees show just how dramatically the Syrian war has shaken the old order. And it provides a fleeting glimpse of the kind of politicking — and transcending of old divisions — that has so far escaped mainstream Palestinian politics and the revolutionary movements that fueled the Arab Spring uprisings.

Iran vs. Saudi: Two repressive blocs face off

Photo Credit: Mohammed Huwais / Stringer

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

By Thanassis Cambanis

BEIRUT — The war in Yemen and the breakthrough nuclear agreement between Iran and the United States have sent the already frenzied Middle East analysis machine into meltdown mode. These developments come fast on the heels of almost too many changes to keep track of: the Iraqi government’s capture of the city of Tikrit, rebel gains in northern and southern Syria, and mass-casualty terrorist attacks in Tunis and Sanaa.

This drumbeat of headlines, however, should not distract us from the larger meaning of events in the Middle East. We are witnessing a struggle for regional dominance between two loose and shifting coalitions — one roughly grouped around Saudi Arabia and one around Iran. Despite the sectarian hue of the coalitions, Sunni-Shiite enmity is not the best explanation for today’s regional war. This is a naked struggle for power: Neither of these coalitions has fixed membership or a monolithic ideology, and neither has any commitment whatsoever to the bedrock issues that would promote good governance in the region.

This is, in some ways, an updated version of the vast and bloody struggle for hegemony that shook the Arab world in the 1950s and 1960s. In that era, a coalition of reactionary monarchs, led by Saudi Arabia, did battle with a coalition of Arab nationalist military dictators, led by Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser. Just like in that past era, every single major player today is opposed to genuine reform and popular sovereignty.

Today’s ascendant regimes are all reactionary survivors — and sworn enemies — of the Arab Spring. The Iranians mercilessly crushed the Green Revolution in 2009, and have invested heavily in authoritarian partners in Iraq and Syria, paramilitary group such as Hezbollah, and non-democratic movements in Bahrain and Yemen. Iran’s leaders are theocrats, but they are savvy and pragmatic geopolitical worker bees: They have backed Sunni Islamists and Christians, while even some of their close Shiite partners — like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, an Alawite, and the Zaidi Houthis in Yemen — belong to heterodox sects and don’t share their views on religious rule.

On the other side of the struggle are the Arab monarchs from the Gulf, run by the same families that brought us the Yemeni war of the 1960s. They have extended their writ through generous payoffs and occasional violence, like the Saudi-led invasion of Bahrain in 2011, which saved the minority Sunni royal family from being overrun by the island kingdom’s disenfranchised Shiite majority.

This Saudi-led alliance is Sunni-flavored, but it would be incorrect to see it as monolithically sectarian.

This Saudi-led alliance is Sunni-flavored, but it would be incorrect to see it as monolithically sectarian. Not long ago, in fact, Saudi Arabia underwrote the same Zaydis it is now bombing in Yemen. The current coalition relies for populist credibility on Egypt, whose governing class is dominated by secular, anti-Islamist military officers. It enjoys dalliances in various conflict theaters like Syria and the Palestinian territories with Muslim Brothers and jihadis. It has drawn extensively on help from the United States — and on occasion from its supposedly sworn enemy, Israel.

Perhaps the best glimpse of the Saudi-led alliance’s goals came when Kuwaiti emir Sabah al-Sabah addressed the Arab League at the end of March, in the meeting that inaugurated the war in Yemen.

“A four-year phase of chaos and instability, which some called the Arab Spring, shook our region’s security and eroded our stability,” the emir thundered. The uprisings, he said, encouraged “delusional thinking” about reshaping the region — perhaps a reference to Iran’s ambitions of regional influence, perhaps a reference to the ambitions of Arab reformers to limit the influence of the repressive states propped up by the Gulf monarchies. To the emir, the only outcome of uprisings was “a sharp setback in growth and noticeable delay in our progress and development.”

This is the crux of the regional fight underway: the old order, or a new one that would transform the balance of power — while changing little else about the way the Middle East is governed. The Saudi bloc wants to turn back the clock to the status quo ante that existed before the uprisings. The Iranian bloc wants to permanently alter the region’s balance of power. Both factions are run by opaque, secretive, repressive, and violent leaders. Neither side is interested in popular accountability, better governance, or the rights of citizens.

For all the doubts about Saudi Arabia’s capacity to craft and execute complex policy, the kingdom has cobbled together a formidable coalition. It quickly signed up most of its clients and partners for the air campaign, including Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Sudan, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates. The United States supported the war, despite its reservations. Of the kingdom’s close allies, only Pakistan has so far resisted pressure to join the fight.

In just the last year, we’ve seen at least two major volte-face. Riyadh helped engineer a regime change in Egypt, ushering President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power. After experimenting with quasi-democracy and a Muslim Brotherhood presidency that defied the powerful Gulf monarchies, Cairo is now governed by a military dictator who walks firmly in lockstep with Riyadh — even promising to dispatch ground troops to a war in Yemen of which he would have probably preferred to steer clear. Qatar, the unbelievably rich emirate that has long cultivated an independent foreign policy, also found itself strong-armed by Saudi Arabia and finally caved. Its emir abdicated in favor of his son, a 34-year-old political novice, and today Doha is reading from Saudi Arabia’s song sheet.

Both examples show that this is not a monolithic bloc bound by uniform ideas of authoritarian rule or Sunni supremacy. Instead, it is a messy realpolitik coalition hammered together by shared interests — and at times by bribes and blackmail. Its members don’t agree on everything: Saudi Arabia hates Russia, in part because Moscow backs Iran and Syria. Egypt loves Saudi Arabia because Riyadh keeps its economy afloat — but it also loves Russia, because it can play off military aid from Vladimir Putin against that from the United States. In public, Sisi praises the Gulf leaders — but in leaked private recordings, he dismisses them as oil bumpkins who can be bilked of their money by more dynamic Arab nations. Qatar no longer openly defies Saudi Arabia, but it still supports Muslim Brothers and jihadis in Syria to the extent it can, and in opposition to Saudi preferences.

Since Saudi Arabia’s gloves came off in Yemen,

Sunnis across the region have expressed a kind of fatalistic relief: At last someone is doing something to confront Iranian influence.

Sunnis across the region have expressed a kind of fatalistic relief: At last someone is doing something to confront Iranian influence. But Tehran has extended its influence carefully, hedging its bets by supporting multiple groups in every conflict zone and always maintaining a degree of remove — if their investments fail, it will have not lost a war in which it was a declared combatant. This blueprint has served Iran well during 30-plus years of intervention in Lebanon and Iraq, and four years of orchestrating major combat in Syria. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has entered the Yemen war directly, and therefore has no cover. It will own the civilian casualties, and inevitably — when the war has no clear and easy outcome — it will own a failure.

History is not on Riyadh’s side in this campaign. Regional wars tend not to go well for invaders; just think of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait or the last Yemen war in the 1960s. The U.S. invasion of Iraq should also offer a cautionary lesson: Many people at the time, including some Iraqis, felt that some major action was better than the status quo, that toppling Saddam Hussein would at the least get a hairy situation unstuck. They were soon disabused of that notion, as Iraq spiraled into chaos.

America should take particular care in this conflict. It has built deep alliances with Saudi Arabia, and it has been far too hesitant to reinvent its dysfunctional relationship with Egypt in the post-Mubarak era. It should act as a brake on Saudi Arabia’s outsized expectations in Yemen, and it should exact a price for any support it gives the war there. Any campaign in Yemen should strengthen, rather than undermine, counterterrorism efforts there, and the United States should share its military know-how in exchange for Saudi cooperation on the Iran deal.

Sure, it’s bizarre to see the U.S. military working with Iran to battle the Islamic State in Iraq, while working against Tehran in Yemen. It’s also refreshing. This isn’t a homily; it’s foreign policy. It’s encouraging to see the United States operating around the edges of a complex, multiparty conflict and finding ways to advance American interests. Its next challenge will be finding new ways to simultaneously pressure rivals like Iran and recalcitrant allies like Saudi Arabia.

But to a large extent, the United States is a sideshow: The main event is the regional struggle for influence between the Iran and Saudi blocs. One need only look at the two major events this spring — the Iran nuclear deal and the capture of Tikrit with the help of Tehran’s military advisors — to get a sense of who’s winning. America’s preferred side has bumbled impulsively from crisis to crisis, buying or strong-arming support and launching military adventures that are likely to produce inconclusive results. Iran’s side, meanwhile, has crafted tight state-to-state relations with Syria and its onetime enemy Iraq, and has deepened its influence in Afghanistan, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Yemen. Despite the theocratic dogma of Iran’s Shiite ayatollahs, the regime in Tehran has managed to position itself as the regional champion of pluralism and minorities, against a Saudi grouping whose philosophy has drifted dangerously close to the nihilism of al Qaeda and the Islamic State.