A Reckoning Will Come in Syria

A missile is seen crossing over Damascus, Syria April 14, 2018. SANA/Handout via REUTERS[Published in The Atlantic.]

It is undoubtedly a good thing that a small international coalition of the willing responded to Syria’s latest chemical outrage with a limited military strike. But it marks only the first step in an effective strategy to stop Syria’s use of chemical weapons—and more importantly, to hold Russia accountable for its promise to oversee a chemical weapons-free Syria.

Syria and Russia have displayed characteristic bluster and dishonesty, warning of “consequences” for a crisis that the Syrians themselves provoked by apparently violating, once again, their 2013 agreement not to use chemical weapons. Any confrontation with destabilizing bullies is dangerous, and there is no predicting whether and how they’ll respond.

Even a limited and justified effort to contain Syria and its allies carries a risk of escalation. The Trump administration, with its capricious chief executive and broken policy-making process, is ill equipped to forge the sort of complex strategy needed to manage Russia, Syria, Iran, and a Middle East in conflict. Nor has it so far displayed much interest in building the international cooperation necessary to implement such a strategy—although it was a pleasant development that the United States was joined this time by France and the U.K. rather than proceeding unilaterally. However, the considerable drawbacks of the Trump administration don’t give the West a pass when it comes to Syrian use of chemical weapons, and Russia’s belligerent expansionism. Both need to be checked and contained, even considering the additional risks Trump creates.

In order to have any real impact on chemical weapons use, the response needs to be sustained. Every time the regime uses chemical weapons, there needs to be a retaliation, which specifically targets the regime’s chemical-weapons capacity—command and control, delivery mechanisms including aircraft and bases, storage, research, and the like. A political strategy is indispensable as well. Since Russia is the guarantor of the failed 2013 chemical weapons agreement, the West needs to keep Russia on the hook for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons. The Pentagon chief suggested that these strikes were a one-off, and only time will tell which of Trump’s preferences prevail.

Deft diplomacy will also be necessary to reduce the risks of wider war. It doesn’t help that Trump is undermining the nuclear deal with Iran at the same time as he is ratcheting up the stakes in Syria. One key determinant now is how much Russia is willing to add action to match its relentless campaign of lies and bluster about Syria and chemical weapons. Another is whether Iran, Assad, and Hezbollah are willing to sit on their hands after these strikes. In the past, all three have been willing to refrain from action despite angry promises.

* * *

The problem is the context. Any American action in the Middle East ought to be embedded in a comprehensive, engaged strategy—which is not likely to be forthcoming. Today, we can be sure that America’s significant moves—from proposals to withdraw military assets fighting ISIS in Syria and Iraq, to promises to degrade the capabilities of Bashar al-Assad or limit the reach of Hezbollah or Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps—will land à la carte, increasing the danger of miscalculation and violent, destabilizing escalation.

At stake is how to manage disorder in the Middle East, and more important still, where to draw the line with a resurgent Russia.

Containing rival powers is an art, not a science. Military planners talk about the “escalation ladder” as if it were a chemical equation, but in reality escalation hinges on unpredictable questions of politics, interests, psychology, hard power, and willingness to deploy it.

Obama’s strategy could most simply be understood as a desire to contain regional fires with minimal involvement, while keeping an equal distance from regional antagonists, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, and difficult regional allies including Turkey and Israel. The U.S. got involved in the fight against ISIS, by this logic, with minimal resources and local alliances that it knew couldn’t outlive the immediate counter-terrorism operation.

In the Syrian context, Obama early on made clear that the United States commitment to principles of democracy and human rights would remain primarily rhetorical. Today, the United States has discarded even many of the rhetorical trappings of American exceptionalism. Trump has made clear that he doesn’t apply a moral calculus to superpower behavior. But he’s also expressed personal outrage about Syria’s use of chemical weapons—and he visibly takes umbrage at being personally embarrassed or humiliated.

Whether one thinks it’s wise or fully baked, President Trump also has a Middle East strategy. He wants to reduce America’s footprint, and disown any responsibility for the region’s wars, as if America played no role in starting them and suffers no strategic consequence from their trajectory. He wants to outsource regional security management to regional allies. Most of this is continuous with Obama’s approach, except when it comes to regional alliances; Obama attempted a “pox on both your houses” balance among all of America’s difficult allies. In his biggest departure from his predecessor, Trump has tilted fully to the Saudi Arabian side of the regional dispute, and has erased what little daylight separated American and Israeli priorities in the Middle East.

This is the bedrock of Trump’s moves in the region—moves that are all the more consequential because they are overtly about confronting, or trying to check, Iran and Russia.

* * *

The United States has a critical national interest in reestablishing the chemical weapons taboo. It also has countless other equities in the Middle East that require sustained attention and investment, of diplomatic, economic, and military resources. A short list of the most urgent priorities includes preventing the resurgence of ISIS or its successors; supporting governance in Iraq; limiting the reach and power of militias supported by Iran; and reversing the destabilizing human and international strategic toll of the world’s largest refugee crisis since World War II. A major regional war will only make things worse.

Given the stated priorities of the president, the most realistic possibility is an incomplete, and possibly destabilizing policy of confrontation, containment, and reestablishment of international norms.

But a reckoning can’t be deferred forever. Iran has been surging further and further afield in the Middle East, to great effect. Russia has been testing the West’s limits mercilessly since the invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. At some point, the United States and its allies will stand up to this expansionist behavior, although there’s wide latitude about where to set limits. When the West, or some subset of NATO, does confront Russian ambitions, there’s no pat set of rules to keep us safe. Such confrontations are inevitable, and dangerous, and unpredictable. The best we can do is enter into them carefully, with as many strong allies as possible, and clearly stated, limited expectations about what we intend to accomplish.

The United States and its allies also need to more carefully distinguish things they dislike (Iranian influence in Iraq) from things they won’t tolerate (Hezbollah and Iran building permanent military infrastructure in the Golan). Rhetoric in the region often conflates the two. Israeli officials, for instance, talk about “intolerable” developments in Syria, but in practice their security policy often allows for a great deal of ambiguity about just what level of military threat they’re willing to tolerate along their frontiers. Iran, Hezbollah, and now Russia have made grandiose claims about retaliating if the United States takes action, but after past strikes by both the United States and Israel, the actual response has been quite restrained.

The United States and its allies need to set limited, achievable goals. The U.S. might for instance stand firm against the use of chemical weapons, or against new military campaigns against sovereign states, but it can’t very well seek to turn back the clock to a Syria free of Russian and Iranian influence.

In addition, the United States can help the world remember who is the author of this dangerous impasse: Syria, Iran, and Russia, who have serially transgressed the laws of war, lied in international forums, and mocked countless agreements, including the shambolic deal that was supposed to rid Syria of chemical weapons in 2013. This won’t justify American actions or give them political cover, but it is a key reason why we’re in such a difficult position in the first place. Despite American restraint, or even American willingness to tolerate war crimes by Syria and its allies, Syria and its allies have insisted on pushing past every limit and exhausting the world’s willingness to turn a blind eye toward abuses so long as those abuses stay within national boundaries.

Finally, to have any impact at all the United States will need to pay consistent and sustained attention. Russia, Syria, and Iran have gotten away with murder, literally, and have found themselves able to run circles around Western governments that still care to some extent about international norms and institutions. They are dangerous, but they are far weaker than their words would suggest. The West cannot deter every action it does not like, yet it can draw boundaries and impose a cost—but it must do so consistently.

This weekend’s strikes have established a bar and set a perilous, but unavoidable, process in motion. What counts is what comes next.

The Logic of Assad’s Brutality

A child and a man are seen in hospital in the besieged town of Douma, Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, Syria. Picture taken February 25,2018. REUTERS/Bassam Khabieh

[Published in The Atlantic.]

Bashar al-Assad, the president of Syria, might have great contempt for the sanctity of human life, but he is not a reckless strategist. Since 2011, he has prosecuted an uncompromising war against his own population. He has committed many of his most egregious war crimes strategically—sometimes to eliminate civilians who would rather die than live under his rule, sometimes to neuter an international order that occasionally threatens to limit his power, and sometimes, as with his use of chemical weapons, to accomplish both goals at once. When he does wrong, he does it consciously and with intended effect. His crimes are not accidents.

The Syrian regime’s suspected chemical-weapons attack on Saturday in Douma, a suburb of Damascus, suggests that Assad and his allies have accomplished many of their primary war aims, and are now seeking to secure their hegemony in the Levant. But two major factors still complicate Assad’s plans. One is Syria’s population, which to this day includes rebels who will fight to the death and civilians who nonviolently but fundamentally reject his violent, totalitarian rule. The second is President Donald Trump, who has expressed a determination to pull out of Syria entirely, but at the same time has demonstrated a revulsion at Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

Almost precisely one year ago, Assad unleashed chemical weapons against civilians in rural Idlib province, provoking international outrage and a symbolic, but still significant, missile strike ordered by Trump against the airbase from which the attacks were reportedly launched. Assad’s regime was responsible for the attacks and its Russian backers were fully in the know, later evidence suggested, but Damascus and Moscow lied wantonly in their hollow denials.

This weekend, it appears, Assad’s regime struck again. Fighters in Douma refused a one-sided ceasefire agreement, and haven’t buckled despite years of starvation siege warfare and indiscriminate bombing. In what has become a familiar chain of events, the regime groomed public opinion by airing accusations that the rebels might organize a false-flag chemical attack in order to attract international sympathy. An apparent chemical attack followed, killing at least 25 and wounding more than 500, according to unconfirmed reports from rescue workers and the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations. The Syrian government and the Russians have once again blamed the rebels, knowing that it will take months before solid evidence emerges, by which point most attention will have turned elsewhere. The pattern is by now predictable. In all likelihood, solid, independent evidence will soon emerge linking the attacks to the Syrian regime.

Assad already has unraveled the global taboo against chemical weapons, in the process exposing the incoherence of the international community. Syria has exposed the international liberal order as a convenient illusion. Western bromides of “never again” meant nothing when a determined dictator with hefty international backers committed crimes against humanity.

Why now? This latest attack in Ghouta, if it holds to the pattern, makes perfect sense in the calculus of Assad, Vladimir Putin, and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The successful trio wants first and foremost to subdue the remaining rebels in Syria, with an eye toward the several million people remaining in rebel-held Idlib province. A particularly heinous death for the holdouts in Ghouta, according to this military logic, might discourage the rebels in Idlib from fighting to the bitter end. Equally important, however, is the desire to corral Trump as Syria, Russia, and Iran did his predecessor, Barack Obama.

After the humiliating August 2013 “non-strike event,” when Obama changed his mind about his “red line” and decided not to react to Assad’s use of chemical weapons, the Syrians had America in a box. The White House signed up for a chemical disarmament plan that proved a farce. By the time the agreement had unraveled and Assad was back to using chemical weapons against Syrian citizens, the public no longer cared and Obama was busy discussing his foreign policy legacy.

Trump’s Middle East policy remains a mystery. He has long appeared unconcerned with rising Russian power in the Middle East, but today tweeted that there would be a “big price” for Russia, Iran, and Syria to pay. He seems to prefer a smaller U.S. military footprint, talking repeatedly about pulling troops out of Syria and Iraq. He’s savaged the deal that shelved Iran’s nuclear program, and doesn’t appear impressed by the shabby chemical-weapons agreement in Syria. He doesn’t seem interested in a long-term strategic engagement in the Arab world, but he’s also not interested in propping up the status quo. His reaction to the Khan Sheikhoun attack a year ago aligned with these preferences: He abhorred the attack and spoke with uncharacteristic humanity about the children killed by Assad, and ordered a pointed but limited response. He wasn’t interested in escalating or intervening against Russia or Assad, but he also had no interest in pacifying or reassuring them.

One result of Trump’s confusing Syria policy is that Assad and his backers can’t quite be sure what America is planning—a pullout or a pushback. Hence another chemical attack, which will test the range of America’s response and, perhaps, will paint Trump into the same corner where Obama’s Syria policy languished.

For Assad, there is utility in such a feint, and no real risk. In 2013, he and the rest of the region braced in fear for an expected American response, which was widely expected to jolt the regional state of affairs. Assad has learned his lessons since then. No meaningful American response will be forthcoming, no matter how hideous the war crime. America remains deep in strategic drift, unsure of why it continues to engage in the Middle East, and prone to spasms of hyperactivity rather than sustained attention.

Although we can’t be sure—yet—exactly what happened in Ghouta, we can be confident that it was no accident. Assad is determined to cement his grip once again over Syria, no matter how thoroughly he has to destroy his country in order to restore it. And with Putin’s backing, he is determined to thoroughly discredit what remains of the international community and U.S. leadership. They can’t be sure what Trump will do, but their apparent cavalier use of chemical weapons on the one-year anniversary of the Khan Sheikhoun attacks suggests they’re reasonably confident that the U.S. president won’t take serious action.

This most recent attack, as tragic as it is, is no turning point. It’s more of the same from Assad and his allies, as they solidify the grisly, dangerous norms that they’ve been busy enshrining since 2013.

ISIS was a symptom. State collapse is the disease

An Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Services member prays in the Old City of Mosul on July during an ongoing offensive to retake the city from Islamic State group fighters. FADEL SENNA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

The collapse this month of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, has been greeted with joy and relief in many quarters, especially among the millions of civilians who directly suffered the extremist group’s rule. Much of the predictable analysis has focused on long-term trends that will continue to trouble the world: the resonance of extremist jihadi messaging, the persistence of sectarian conflict, the difficulty of holding together disparate coalitions like the clumsy behemoth that ousted ISIS from its strongholds in Raqqa and Mosul.

But jihadis and sectarians are not, contrary to popular belief, the most important engines of ISIS, Al Qaeda, and similar groups. Nor are foreign spy services the primary author of these apocalyptic movements — as many around the world wrongly believe.

No, the most critical factor feeding jihadi movements is the collapse of effective central governments — a trend in which the West, especially the United States, has been complicit.

An overdue alliance of convenience mobilized against the Islamic State three years ago, but only after leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had taken over enough territory to declare statehood. The ISIS caliphate was as much as a state — for as long as it lasted — as many other places in the Middle East. Most of the coalition members detested ISIS, but only the local members from Iraq and Syria whose families were dying or suffering under Islamic State rule were fully invested. For the rest of the anti-ISIS coalition, fighting the caliphate was one of many other priorities.

The glacial, slow-moving, coalition united against ISIS but bound by little else. It is sure to dissolve quickly now that the emergency is over.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson called the defeat of the ISIS caliphate a “critical milestone,” and Iraqi prime minister Haider Abadi hailed “the failure and the collapse of the terrorist state of falsehood and terrorism” that ISIS had proclaimed from Mosul. Yet even as the partners cheered the defeat of one state, they acknowledged the need to rebuild another one — Iraq — if they want to avoid cyclic repetition of the same conflict. Abadi, like American commanders on the ground, described a daunting task: to unify feuding militias, provide services to long-ignored populations, and perform effective police work — in short, to finally extend a functional state throughout Iraq.

In the years since terrorism has become an American obsession, much attention has focused on the root causes of nihilistic violence. The latest iteration of this vague quest, which attracts billions of dollars in government funding, is “countering violent extremism.” But it’s entirely possible that violent extremists aren’t really the problem at all; they only matter in places where the state is too weak to provide security, or too incoherent to explain why terrorist attacks are merely a crime, rather an existential threat.

Here’s another way to put it: There is no after ISIS, because ISIS isn’t the problem. The collapse of states is.

THE MOST EFFECTIVE INFANTRY troops in the war against ISIS, in fact, come from movements whose long-term aspirations are accelerating the collapse of the state order in the Middle East. To be sure, the key fighting groups — the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga, the Shia militias referred to as the Popular Mobilization Units, and the Syrian Kurds from the PKK — are nothing like ISIS. They aspire to political and territorial power without the murderous, nihilistic sectarianism of the Islamic State. At the same time, these groups all profoundly oppose central government in the areas where they live. Some, like the Iraqi peshmerga, want to form a smaller, independent Kurdish republic, even though they are internally divided in a way that promises future strife and civil wars, not harmony. Others, like the Shia militias, want to carve out an autonomous state of their own that functions in the lee of a hobbled central government.

The United States has contributed mightily to this dismal state of affairs. To solve an immediate problem, ISIS, it guaranteed a still-more toxic long-term problem: an ungovernable zone stretching from the Mediterranean to the Zagros Mountains, where death squads, militants and fundamentalists will continue to proliferate.

And as ISIS taught us well, local problems rarely remain local.

The central problem to face after the ISIS caliphate, then, isn’t whether the Islamic State will return or in what form, but when we’re going to tackle the epochal and complex challenge of supporting coherent states in the Middle East. The United States has been a major catalyst of the current entropy and chaos in the Arab world — sometimes through direct destabilizing actions, like the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and other times abetting long-term corrosion by backing ineffectual, tyrannical despots who ransack their own states in order to cling to power.

Much of the immediate response to the collapse of the caliphate centers on Sunnis, and is cast in simplifying sectarianism. Can their grievances be better addressed, to stop their ranks from breeding foot soldiers for nihilists? Can Shia partisans slake their thirst for power and share enough of spoils to coopt disenfranchised Sunnis?

There are some important points nested in this type of analysis, but it overlooks one essential fact: Factors like sectarian identity, jihadi extremism, and mafia corruption only become dominant pathologies in areas where the state is no longer fully in control. The Islamic State can claim adherents in dozens of countries. But an Islamic State insurgency only rises to central importance where a failing state has left a vacuum.

The glacial, slow-moving, coalition united against ISIS but bound by little else. It is sure to dissolve quickly now that the emergency is over.

Compare, for example, the ISIS campaign in the Levant, where Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi established his short-lived state, to the far less potent Islamist insurgency in Egypt. Sure, followers of the Islamic State have murdered civilians, attacked state targets, and created limited mayhem in parts of Egypt — but the Egyptian government and security services remain powerful and as much in control as they ever have been.

State narratives and identity also limit the power of the nihilist narrative. Governments in Iraq and Syria struggle to convince all their citizens that the state functions everywhere and cares for all its citizens. But ISIS attacks on civilians in places like the United Kingdom, France and Egypt, cause consternation but don’t raise questions about the very viability of those states.

The Islamic State is a murderous movement. The existential threat comes not from ISIS but from state failure — a failure that precedes, rather than results from, the rise of violent fundamentalists.

THE ISLAMIC STATE MADE a great fuss about tearing down the old borders drawn by colonial powers. Many groups that otherwise detested ISIS shared the extremists’ distaste for the artificial borders that divided historical neighbors and cobbled together problematic, hard-to-govern entities.

That discussion about viable borders, however, created confusion. Some took the rise of ISIS as evidence that the nation-state itself had entered the final state of eclipse. That view dovetailed with a fascination that grew since the end of the Cold War among some academics and futurists, who believed the global order had transcended the era of states.

In its most breathless incarnation, pop theorists like Parag Khanna celebrated a “nonstate world,” in which states were just one of many players happily competing with free-trade zones, corporations, cities, empires and other levels of organization to maximize utility.

More reserved scholars also concurred that we had entered a post-state era. Some argued that the future held more shared-sovereignty projects, like the European Union, in which states would give up power in exchange for the efficient and humane economies of scale offered by supra-national institutions. Utopian internationalists like Strobe Talbott wrote warmly of a “world government” in which scientific management principles would replace parochial nationalism.

Pessimists agreed that the state was in irreversible decline, but believed something worse would take its place: tribes, militias, unaccountable local strongmen, and predatory companies.

The conflicts since the Cold War point toward a different struggle, between strong and weak states, rather than between states and some mythical nonstate world.

At West Point after the 9/11 attacks, George W. Bush declared the world had already resolved the struggle against totalitarian ideologies during the 20th century. “America,” Bush said as he unleashed a series of wars that continue 15 years later, “is now threatened less by conquering states than we are by failing ones.”

A case in point is ISIS, which was in fact enamored and obsessed with a very traditional view of power and statehood; their project wasn’t to erase the state, but to invent a new one.

The nation-state is a relatively new phenomenon, dating back just a few hundred years. But states need not be based on nationalism. In fact, the most resilient and powerful states have often stoutly rejected a nationalist identity, instead embracing an identity based on empire (Britain), geographic scale (the United States), or continuous civilization (China).

“The state continues to be the basic building block of politics. Fragile states don’t diminish that fact,” said Alasdair Roberts, incoming director of the school of public policy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Two years ago, Roberts argued that after brief period of uncertainty, the last few decades had shown that states remained the seat of power, in an essay called “The Nation State: Not Dead Yet.”

In the United States, critics of globalization feared that America was surrendering power and sovereignty to organizations like the World Trade Organization. Roberts says that recent developments, especially since the election of Donald Trump, proved what many politicians had said all along: “We’re delegating authority, and if we want to get it back, we can get it back.”

A strong, functional state might subcontract authority to the United Nations, or to an oil company, if such an arrangement suits the state’s interests. But all across the world, in rich countries and poor, states have quickly reclaimed their prerogatives when they believed their national interests were threatened by a trade agreement or an international court decision.

In our times, the Middle East has been the world’s biggest exporter of militants and destabilizing violence.

But the Middle East is not inherently violent or unstable. States have managed to assert authority and control their territory — although sometimes in savory ways — at many points in modern history. Governments in Turkey, Iran, and Arabian Gulf maintain a monopoly of force and a passable piece, ruling ethnically diverse populations (although with limited political rights for citizens). Flashpoints like Syria and Yemen knew stability for many years during the last generation. State-builders like Kemal Ataturk and Gamal Abdel Nasser reversed periods of decline and fragmentation, showing that it’s possible to bring unity and extend the reach of a bureaucratic state even in unruly and poor places.

We are living with the results of failing states in the Arab world. The best alternative is to see them replaced with functional ones. In some cases, that might mean holding our noses and accepting effective but cruel leaders. In others, it will mean exerting pressure and sometimes using force.

It doesn’t work to waffle, as Obama did when he tepidly supported the Arab uprisings in only some countries, and then just as tepidly stood by some of the dictators who mercilessly crushed popular revolts. It also doesn’t work to confuse tyrants who stay in power while eviscerating the state, like Gaddafi in Libya and Saddam in Iraq, with distasteful rulers who maintain a functioning state and are therefore effective, like the Saudi monarchy.

For the United States, a smart policy requires commitment. We know Bashar Assad will never create a sustainably stable government in Syria, because of his determination to wipe out rather than coopt dissent. Iraq is less straightforward; the United States cannot stand by passively as the state breaks up. But that requires clearly choosing sides: openly support Kurdish secession, and division of Iraq into smaller, ethnic or sectarian states, or openly repudiate the Kurdish drive toward independence and put pressure on Baghdad to extend its writ. The current course of intentional ambiguity only promotes the worst alternative — state decline.

When possible, we ought to promote humane governance. But in all cases we must insist on effective state power. We have seen the alternative in Iraq, where the United States and other guarantor powers, including Iran, let the government in Baghdad decay, only intervening when ISIS took control of nearly one-third of the country.

A state that is both cruel and ineffective is an albatross for the whole global order. If we want to counter violent extremism, we’re going to need a world of effective governance — and for now, the only place that’s likely to come from is strong states.

Only Humane Governance Can Erase Legacy of ISIS

[Published at The Century Foundation.]

This summer, the Islamic State will probably lose its capitals in Syria and Iraq, and possibly, any hope of surviving as a traditional territorial state. For three years, however, the ISIS caliphate functioned as a state—blood-trenched, appalling, and wildly unpopular—but a state nonetheless.

Its fall certainly doesn’t preclude other jihadi movements from replicating Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s feat in the future. And the Islamic State’s material success highlighted just how awful many other governments in the region are. Too often, Middle Eastern states tolerate rampant torture, repression, surveillance, and rights-stripping; the nihilistic horrors and excesses of ISIS weren’t categorically different, but they took these practices to another level.

With the Islamic State downgraded from contender state to insurgency, we now would do well to ask: What is the best long-term antidote to extremist violence?

The answer might lie not in countering violent extremism, but in investing in strong states. And crucially, our experience with state failure and abusive governance in the Middle East should force us to update our definition of a strong state. It is not, as American policy makers have historically believed, a state ruled by a strongman willing to accept phone calls from Washington.

In actuality, a strong state is one that effectively controls its territory and governs its citizens, providing stability and continuity though humane rule and rights for its citizens. Any state that rules through caprice and violence is inherently unstable, even if it possesses a monopoly of force within its borders. Such are the lessons of the failed and failing states of Arab region, whose erosion has allowed violent extremism to flourish. To significantly reduce extremist ranks, it does not suffice to target individuals. A country has to build (or rebuild) an alternative to authoritarian thuggery: a bureaucratic state and security services that actually provide security rather than repress citizens.

Effective governance means humane governance. Anything else is a short-term fix.

Fighting the Wrong War

There are two things that the West, and primarily the United States, must grapple with in order to reverse the jihadi tide that will continue to lap at its shores long after Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s Caliphate recedes as a grisly but mercifully short chapter in geopolitical history.

First, we need to embrace robust liberal pluralism as our most potent weapon against the ideology of jihadi nihilism, violence, and intolerance. Over the long haul, the West’s openness, prosperity, and education make for better societies than anything on offer from repressive religious extremists or Middle Eastern despots. Not only should we refrain from apologizing for this characteristic; we ought to tout it as the leading edge in our counter-extremism campaign.

Second, we need to admit that our misguided foreign policy and indiscriminate use of violence in the wars against terror since 9/11 have bred a great deal more outrage, extremism, and terror than they have contained. We might not have created the problem, but we have definitively made it worse. We continue to employ the same fruitless “capture, kill, contain” techniques, to our continued disservice. As a result, the cancer that presented as the “caliphate” will in due course metastasize somewhere else.

The prime candidates for the next outbreak of hypertoxic jihadi extremism are places where the United States, or allies with its support, are creating famine, mass displacement, and wantonly killing civilians—while supposedly pursuing extremists, using the hard-to-monitor blunt weapons of aerial bombing, drones, and special forces.

Such battlefields, sadly, exist today in places that only occasionally draw attention, like Yemen, Libya, and Afghanistan, and also in more uniformly ignored war zones in places such as Mali and Nigeria. Declining and eroding states have opened the gates to extremists of all sorts in a long list of poorly governed spaces, including parts of the Sinai, Somalia, South Sudan, Lebanon, and the Philippines.

Embracing Conflict and Despots

By the end of his time in office, President Obama was deploying U.S. special forces simultaneously to 139 countries—that is, two-thirds of all the countries in the world. Not all of those deployments were active conflict zones, but the United States is fighting in undeclared wars in several, including Syria and Yemen. Endless war only serves to weaken states—the very things we need in order to live in a secure world.

The coalition against ISIS relied on nasty alliances of convenience with dictators, authoritarians, and militiamen, many of whom were in thrall to sectarianism and bloodlust. This devil’s bargain is the same principle that guided the Obama administration’s clumsy embrace of the Gulf Cooperation Council monarchs and their war in Yemen, and which drives the Trump administration’s much warmer embrace of Arab despots.

In his debut foreign trip in May, President Trump cast aside any pretense of valuing democracy or decency in our allies. “We must seek partners, not perfection—and to make allies of all who share our goals,” President Trump told the heads of state assembled in Riyadh.

Trump echoed the refrain of the region’s despots, who self-servingly claim that their failing brand of governance is the only alternative to the Islamic State and its imitators.

“Our partnerships will advance security through stability, not through radical disruption,” Trump said. “Wherever possible, we will seek gradual reforms—not sudden intervention.”

History might prove him wrong, but he was only saying out loud a view privately shared by many of his White House predecessors. Iran was the only state singled out for doing anything to promote terrorism, as if state policies adopted by American allies, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iraq, and Egypt, had played no role in abetting violent extremists.

This mistake has become a cornerstone of American foreign policy, repeated over and over again. If unshakeable support for despots provided insurance against runaway violence, today we’d be living in a quiet, peaceful world. It’s not just that devil’s bargains are distasteful and betray our core values; they also don’t work.

Only effective, humanistic states provide an alternative to a governance wasteland that promotes apocalyptic preachers and young people who embrace death in the absence of a sustainable future.

Short-Term Fixes

States in the Middle East and North Africa region are failing. Successful states must exercise their authority over, and elicit loyalty from, a plurality of citizens. Even homogenous states are to a certain degree multiethnic and multisectarian. Difference must be managed, not ignored or suppressed.

Such states have been built before in the Middle East, and have prospered. Even in today’s dark period, there are plenty of states that muster a significant degree of state authority and competence. Egypt, until recently, was an example of how a flawed state could still perform most of its core executive and security functions.

It’s a debatable proposition that authoritarians are the answer. History suggests that sometimes authoritarians can be effective long-term leaders. Their success depends on resources, competence and a commitment to results. Gamal Abdel Nasser was no democratic civil libertarian, but he was genuinely invested in modernizing his country. For decades, he delivered results that seemed to mitigate his authoritarian tendencies. Toward the end of his rule, the balance had shifted—an increasingly erratic and paranoid Nasser presided over a state that stagnated economically and no longer proved capable of securing its borders. Hence a period of domestic paralysis coupled with the catastrophe of the 1967 war.

There are plenty of other examples, ranging from the resurging conflict in southeastern Turkey to flare-ups in rural Tunisia, to suggest that a cloak of stability thrown over incompetent rule and mass repression is only a short-term fix: the simmering violence in every Middle Eastern conflict zone testifies to it.

In the post-colonial Middle East, we mostly see weak states. Policymakers by necessity often focus on the crumbling and collapse, since they cause the biggest problems. But let’s not forget that the reverse is possible. A strong state, an effective state, even a decent state, can be imposed in a country that appears in the grip of anarchy and chaos. It’s happened before and could happen again.

Must a Strong State Be a Just State?

A state that succeeds as a state provides basic security and services. It can be an awful state in many other regards, usually by abusing minorities or withholding political rights, but consolidated states offer continuity, loyalty and a kind of security that’s been in increasingly short supply. (I have written elsewhere about the resilience of the state as the main unit of analysis; here I want to expand on the possibility that only a humane, rights-based state can provide lasting stability.)

The default—the continuing collapse of states in the Middle East—promises more instability. To reverse the poisonous forces ascendant in the Middle East, states must consolidate power and the impose central authority on the full spectrum of militias and political stakeholders. Otherwise, sectarianism, local warlord rule, runaway mafias, and foreign intervention will continue to steer events in places like Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

It is possible that a state can succeed without humanism. Saudi Arabia is an excellent test of the proposition. The monarchy offers no pretense of rights, but promises to take good care of its citizens. The most colossal failures in recent times, like Bashar al-Assad, Saddam Hussein, and Moammar Qaddhafi, failed not because of their egregious human rights abuses but because they hollowed out the state apparatus and lost physical control. So it’s possible that a well-executed, abominable police state can indefinitely keep the lid on a population. The popular explosions in Iraq, Syria and Libya, however, suggest that brute-force repression is always a temporary solution.

But for a state to truly thrive, it needs to address the basic needs of its people, which include a modicum of political rights. Otherwise they will not be invested in the state which rules them. We need new, better models of governance, which are inclusive and provide genuine political feedback. They need not look just like Western democracies. Nor, however, can they trample their people’s rights. Citizens in the Middle East, like everywhere else in the world, demand decent treatment from their government, and they expect some say over how they’re ruled. They also have a historical memory of times and places when different identity groups coexisted without violence, as well as when political loyalties came with dividends—and not merely with the threat of reprisal against the disloyal.

The long-term recipe for a Middle East free from the scourge of violent extremists is the same as it is everywhere else: effective rule by states both strong and humane, that recognize pluralism, rule of law, and human rights.

COVER PHOTO: TWO MEN CARRY SICK AND INJURED CHILDREN TO SAFETY THROUGH THE RUBBLE OF A STREET IN THE OLD CITY OF MOSUL ON JUNE 24, 2017. © UNHCR/CENGIZ YAR.

What Did the Trump Administration Just Do in Syria?

[Published in The Atlantic.]

If the presence of such fighters in the area is confirmed, the airstrikes, and the likely military escalations to come elsewhere, may mark an end to a long period during which the United States avoided direct military clashes with Iran or Iranian-backed proxies. If U.S. troops are now engaging directly with Iranian militias, escalation in the absence of a well-wrought plan could inflame the conflict in Syria and further afield. On the other hand, for all Iran’s bluster, the Islamic Republic, a staunch ally of Syria, will have to re-calibrate its own expansionist ambitions in the Middle East if it encounters meaningful resistance from the United States after nearly a decade of only token or indirect opposition.

The stakes are high: Iran’s regional rivals have staked their hopes for a reversal of fortune on Trump’s willingness to embrace traditional Sunni allies and take military action against Assad, while Iran and its allies believe themselves on the verge of a total victory in Syria.

And while the strike may have been undertaken more in self-defense than as part of any shift in policy, the Trump administration has been actively seeking ways to repel Iran, canvassing the Pentagon as well as U.S. allies in the region for suggestions about where and how to draw lines against what it views as Iranian expansionism. American experts with experience in the region, and in the U.S. government, say they have been consulted about possible pressure points. In my conversations with senior Arab officials, they have shared their own proposals in detail. The strikes against Tanf may well suggest that America is moving out of the planning stage and into a period of military action intended to abate Iranian momentum.

So far, there are no indications that the Trump administration is doing any of the necessary groundwork to insure against blowback or out-of-control spiraling as America appears to turn from accommodation and containment to military force. The Obama administration pursued a cautious, conciliatory approach to Iran, avoiding any direct clashes in the belief that all other concerns were secondary to the nuclear negotiations, and that a relatively minor clash over Syria or Yemen could upend years of talks to freeze Iran’s nuclear program. In practice, the regime and its clients learned that they could behave as recklessly or maximally as they wanted in pursuit of their interests in the Middle East without fear of a robust U.S. response, even in places like Iraq. Obama administration officials say they believe this approach allowed them to win international support for the nuclear deal and to portray Iran, rather than the United States, as the problem party in the negotiations.

It’s just as likely that nuclear negotiations would have produced the same outcome even if the United States had pushed back against Iranian actions in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, prior to the conclusion of the deal. But once the nuclear deal was concluded, Obama made a poor choice, joining forces with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in an ill-planned campaign in Yemen that has hobbled the state, wantonly targeted civilians, opened new space for al-Qaeda, and strengthened, rather than reduced, Iranian influence over Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Meanwhile, he left Iran and its proxies a free hand in Iraq and Syria. The result today is a triumphalist Iran, whose allies and proxies can claim a dominant position in Iraq and Syria, and whose military and political rise was, in many instances, directly abetted by the United States.

The smartest bet (and the least likely one in a Trump White House) would avoid direct military clashes and instead use political pressure to marginalize Iranian proxies in Iraq, and military force against Iranian allies in Syria. It’s unrealistic to try to erase Iranian influence in the region, as the Arabian monarchs deluded themselves into believing they could do in Yemen. What is realistic is to deny the Iranians and their allies some of their goals, such as a swift victory over Syrian rebels in the south and southeast, while making other goals, like domination of Iraq and Syria, more costly.

Senior officials in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia (like most of their counterparts throughout the Middle East) have made no secret of their disdain for Obama, who they believe abandoned his traditional allies and, in general, neglected the turmoil that has engulfed the region. Now they are fully invested in Trump, a gamble that senior officials from the Gulf gleefully describe in private, and fully expect will pay off. They believe he will value the colossal support they give him by purchasing American arms and supporting global energy markets, and that in return, he will take their suggestions about how to manage regional security threats. The narrative they’re selling is seductively simple: The region faces a single destabilizing extremist threat, and the supposedly complex web of forces at play are really just different faces of the same phenomenon. Gulf envoys portray the Muslim Brotherhood, al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and even Iran, as different brands and incarnations of the same violent extremism—a simplistic and simplifying approach that leads to terrible policy prescriptions, but which comfortably echoes Trump’s tendency to vilify Islam.

Therein lies the danger. An inattentive and reactive administration in Washington that has decided it’s high time to stop Iran might fumble for whatever opportunities present themselves. An amped war in Yemen after a high-priced lobbying campaign by Gulf allies? Why not. A one-off strike against Hezbollah, Iraqi-Shia paramilitaries, or some other Iranian ally in Syria, so long as there’s no risk of hitting Russians? Sure.

But what happens when Iran and its allies, inevitably, strike back? They’ve been in this game for decades, and they are masters at bedeviling U.S. goals and striking against U.S. interests using a web of proxies and allies that are often difficult to connect directly to Tehran. Furthermore, as spoilers, Iran’s side often needs only to make a splash, not necessarily to win outright.

The best way forward would entail a systematic and contained series of strikes against targets of opportunity—protecting civilians and U.S.-backed rebels when possible, continuing to strike jihadists while denying cheap successes for the Assad regime, and, above all, exacting a military cost for atrocities and war crimes. None of these moves will expel Iran from Syria or diminish its status as a dominant regional power—a status it earned over many long decades of hard work as a spoiler, ally, proxy-builder, and kingmaker. While the United States swung in and out of the region and the Sunni royal families fell victim to their own lack of capacity as states with weak institutions and mercurial governance, Iran stuck with its long game. Successfully standing up to it today means restoring balance and halting its forward momentum.

Washington can learn a bit from Iran’s playbook. If the United States plans its strategy right, it doesn’t have to beat Iran and its proxies—all it has to do to shift momentum is make it expensive for Iran (by destroying some of its troops or proxies) and for once make a credible show of using air power to defend American allies on the ground. It can also, with minimal resources, prevent Iran and Assad from reclaiming Syria’s south and southeast in a cakewalk.

The Trump administration’s military moves in Syria could signal the beginning a concerted effort against Iran. But given the its anti-Muslim record, impulsiveness, and general chaos, it’s just as likely that renewed U.S. attention to the Middle East will mean military intervention without a sound strategy—and will spawn a new generation of problems rather than the solving existing ones.

After Khan Sheikhoun, “War Crimes” Might Have No Meaning

RESIDENTS IN SARAQIB, A CITY IN THE SYRIAN PROVINCE OF IDLIB, PROTEST THE CHEMICAL ATTACKS IN NEARBY KHAN SHEIKHOUN.

SOURCE: FACEBOOK/EDLIB MEDIA CENTER

[Published at The Century Foundation.]

The latest chemical weapon attack in Syria assaults the most foundational values of our international order just as surely as it shocks the conscience. The attack on Khan Sheikhoun on April 4 bears the hallmarks of previous regime attacks; it will take time to fully assess the evidence, but there is already a powerful body of evidence implicating Syria’s government in the strike.

What does “never again” mean if one of the most closely watched dictators in the world can repeatedly get away with violating a global ban on chemical weapons in a scorched-earth campaign against the last holdouts resisting his abusive regime?

How are we in the future to rely on the delicate web of international institutions erected after World War II, on matters of core concern to humanity (and for that matter, to U.S. interests), if we allow those institutions to be gutted by a coalition of autocrats willing to brazenly test the resolve of a Western-dominated international order?

There are plenty of painful matters to unpack as a result of the apparent regime attack on Khan Sheikhoun, which will take its place in the long catalogue of horrors that is Syria’s civil war.

Some questions concern Syria, and its likely future under Bashar al-Assad, the country’s newly confident hereditary ruler. What kind of daily atrocities can Syrians expect from a ruler who, as he arcs toward victory, demonstrates such rapacious thirst not for reconciliation but for vengeance against civilians?

Other questions affect the entire global community of nations: What meaning remains in international humanitarian law—the laws of war—that are supposed to govern what weapons belligerents can use, how they choose their targets, and how they can treat their prisoners of war? Such laws are often observed in the breach, but we are testing the limits of how often war crimes can be committed without rendering the whole concept terminally abstract.

After World War II, even powerful nations understood they had a stake in limiting the horror of total war; after all, they had all just experienced its extremes—and most understood they had committed some atrocities as well as suffering at enemy hands. The Geneva Conventions of 1864 were the first laws governing warfare, but international momentum really coalesced with the Geneva Conventions of 1949. From this shared understanding—and not from some spirit of altruism—were born a new set of norms: No genocide, no chemical weapons, no torture of prisoners of war, no completely indiscriminate bombing.

Of course, since the end of World War II, these norms have been tested and transgressed, at times by the United States. But the mutual agreements survive because they have given rise to an extensive web of laws, treaties, and institutions, and because even powerful nations that occasionally abuse those laws tend to do so while claiming to uphold them—a surprisingly effective way of propping up even a partially observed norm.

Tests of international will took on a new and more toxic form in Syria’s civil war. Assad’s use of chemical weapons ultimately strengthened his regime’s standing rather than turning it into a pariah. His temerity and the feckless international response, together, strike a body blow against an international consensus that was already weakened by the excesses of the American-led global war on terror after 9/11.

The first step came in August 2013, when Assad killed more than a thousand civilians in a nerve gas strike on the Damascus suburbs. It was the one move that risked punitive strikes against the regime, or potentially more broadly, bringing the United States fully into the war on the side of the rebels. Assad risked it anyway. American airstrikes on Damascus appeared imminent until a surprise eleventh-hour agreement was reached to dismantle Syria’s entire chemical weapons stockpile. Russia and the United States brokered the deal, and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (one of those all-important international organizations upon which we depend for what rule of law persists in the global order) oversaw its implementation.

But the deal faltered after the first year, in a painfully chronicled failure. In documented attacks since 2013 it appears that Assad’s forces have used chlorine, which is not listed in the Chemical Weapons Convention. If sarin or a similar nerve agent was used in the Khan Sheikhoun attack, it would represent a significant shift.

Today, American foreign policy aims for transactional, whitewashing failed governance and human rights abuses if dictators are willing to cooperate on counterterrorism.

The strike in Khan Sheikhoun, if it is eventually proven to be a regime act, will mark the second brazen contravention of international norms—and this time, it comes at a moment when Bashar al-Assad already appears on the cusp of obtaining most of what he seeks from his erstwhile enemies, potentially prevailing against long odds. Why risk that imminent victory and possibly turn a President Trump who appears predisposed to deal with Damascus against Assad?

We might never know the motive for the gas attack, but its impact will be clear. The countries that have voiced opposition to Assad will now have to consider whether to match actions to their words. And Russia and China, the most powerful countries that sympathize with the transactional dog-eat-dog view of international relations, will have to decide whether to exercise their United Nations Security Council vetoes to limit any response to Khan Sheikhoun.

Unless the unlikely occurs and a sizable portion of the international community stands against the outrage, we’ll be another step closer to an international order without order, a world of war where there’s no longer any such thing as a war crime.

What Could Possibly Motivate a Chemical-Weapons Attack?

A picture taken on April 4, 2017 shows destruction at a hospital in Khan Sheikhun, a rebel-held town in the northwestern Syrian Idlib province, following a suspected toxic gas attack.

Omar Haj Kadour / AFP / Getty

[Published in The Atlantic.]

At present, U.S. intelligence officials say the attack has the “fingerprints” of an Assad regime strike. In a statement on Tuesday, President Donald Trump directly condemned Assad for the attack, but suggested that President Barack Obama’s weakness set the stage for the continuing use of chemical weapons in Syria. “Today’s chemical attack in Syria against innocent people, including women and children, is reprehensible and cannot be ignored. … These heinous actions by the Bashar al-Assad regime are a consequence of the past administration’s weakness and irresolution,” the statement read.

None of this answers the central question of motive, which remains as much a mystery today as it was after the 2013 nerve gas attack on the Damascus suburb of Ghouta. There are a few clues, however. Some can, indeed, be found in Obama’s hasty retreat from his red line on chemical weapons. Another can be found in Trump’s warm words for Egyptian dictator Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, uttered on Monday at the White House during the official debut of a new, unabashedly transactional foreign policy that marginalizes issues of human rights and governance.

This is not to suggest a causal link between Trump’s bear hug of Sisi and the attack the following day on one of the last persistent rebel holdouts in Syria—the Ghouta attack took place after Obama explicitly threatened retaliation for such a thing, after all. But the brazenness and horror of the attack suggest a gutting of the very heart of foundational international norms. Whether intentional or not—and it might well be a calculated move—this attack marks a second frontal assault on global norms against chemical warfare, along with the international institutions that undergird that ban.

The first challenge, the Ghouta chemical attack in August 2013, was sadly successful. It put to rest any notion that the U.S.-led international order was willing to enforce its red lines, even one as globally important as the taboo against chemical weapons, which grew out of universal horror at the gas attacks on the trenches during World War I. Obama’s red line, and the flawed deal that followed that dismantled most but not all of Assad’s chemical weapons capacity, taught Syria and its backers an important lesson: at least in this current epoch, the guarantors of the international order are no longer heavily invested in its ethical core or its literal enforcement. Obama laid down only one explicit marker that would prompt him to intervene in Syria—the use of chemical weapons. Assad used them anyway, and found great reward in testing even the most supposedly sacred limits. That was the real lesson of 2013, and it wasn’t lost on Assad, Sisi, Putin, or other transactional authoritarians.

For nearly the entire Syrian civil war, Assad has offered a deal to the foreign powers that backed the rebellion. If these foreign governments returned to the regime’s fold, all would be forgiven, and Assad’s nexus of intelligence services would resume (or in some cases, start) a morally compromised but effective counterterrorism partnership against common enemies, from ISIS to jihadi operatives now in the West. American and European diplomats expressed distaste for such a Machiavellian deal. But after Europe’s unity fractured in the wake of the refugee crisis, some of its governments began, discreetly, to discuss the inevitability of Assad’s permanence. While his gulag and the methods of his intelligence services horrified them, they also could imagine tangible benefits from intelligence cooperation to root out terrorists. Privately, Syrian officials remind their Western counterparts that their extensive files could help them identify militants or jihadis currently hiding in plain sight in Turkey, the European Union, or the United States. Obama gave up on regime change, but was eager to keep his distance from the dictator in Damascus.

Institutions and governments that stand by idly or ineffectually as Assad makes a mockery of the chemical weapons taboo and the agreement that supposedly emptied Syria of chemical weapons years ago will find themselves ill-equipped to cope with later crises about which they care far more than they do about Syria.

This leads back to the question of motive.

The U.S. government’s confidence aside, it will take time for conclusive proof about this latest attack to emerge in the public sphere, as it did in 2013, of the regime’s culpability. From a Syrian tactical viewpoint, this attack was utterly gratuitous. Syria’s government, which at this stage is handily winning the civil war, does far more killing with conventional weapons. So in terms of the human toll, chemical attacks are but one piece in a horrifying network of crimes.

But the attacks do more than just murder Syrians: they expose the international order as a sham, and weaken the same institutions that are supposed to restrain Assad and his chief backers, Russia and Iran. A weakened and humiliated United Nations—or European Union or United States for that matter—behoove the maneuvers of Moscow, Tehran, and Syria, which more often than not find themselves targets of the wrath of an international order dominated by Washington and Brussels.

It could be that the attack in Idlib was the work of a rogue or a madman. But it’s all the more likely, given the carefully studied impact of the 2013 chemical fiasco in Syria, that Assad expects even greater dividends this time than he reaped during the last round. If he can drop chemical weapons on the same day that a conference in Brussels is discussing plans to reconstruct Syria, without any substantive response, then he’ll inch even closer to his current goal of winning a Western-funded rebuilding plan on his own terms. He hopes to cudgel the West into funneling reconstruction money through his regime, which committed most of the destruction in the first place. It’s absurd that until last year, the same Western governments that were calling for Assad’s ouster and funding for armed militants to overthrow him would now pay to restore his abusive authority— it’s also very possible.

A chemical attack seems folly at this pivotal moment, with Europe and the United States pondering whether to reluctantly restore relations with Assad. But sadly, it’s the kind of gamble that has worked for Assad in the past.

As usual, the first victims are Syrian civilians, caught in Assad’s total war. But an equally important casualty might be what remains of the international institutions that are supposed to fight war crimes and atrocities. Today Syrians suffer. Tomorrow, the world.

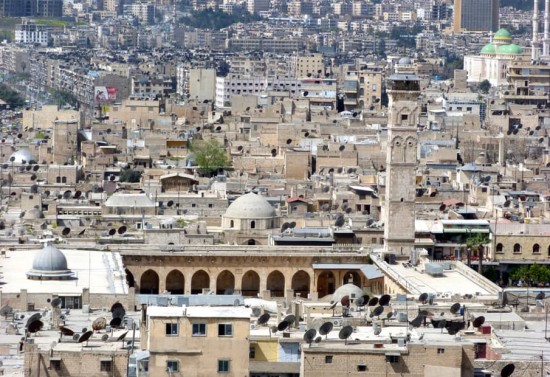

Aleppo’s fall is our shame, too

Syrian residents, fleeing violence elsewhere in Aleppo, arrive in the city’s Fardos neighborhood Tuesday. STRINGER/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Published in The Boston Globe.]

As the last rebel neighborhoods in Aleppo fell this week, Samantha Power, America’s ambassador to the United Nations, excoriated Russia, Syria, and Iran for authoring what will prove to be the signal atrocity of our time.

“Are you truly incapable of shame?” Power asked. “Is there no act of barbarism against civilians, no execution of a child that gets under your skin?”

Hundreds of thousands chose to stay in what they proudly called “Free Aleppo,” eschewing safe routes when they still existed and vowing to preserve their alternative to Syrian President Bashar Assad even if it meant death.

This week, that horrific choice materialized. Assad’s regime destroyed rebel Aleppo step by step, using Russian airpower; legions of militiamen from Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen and Lebanon; and the barrel bomb, another of the war’s sad innovations. Syrian rebels in Aleppo had warned for a year and a half that a siege was inevitable unless their backers, including the United States, provided them at least with air support and a steady supply of bullets and cash.

Western officials decried the unfolding tragedy in Aleppo, but their actions guaranteed this week’s genocidal denouement. The United States withheld basic support to vetted rebels. Turkey diverted its proxies to deal with the Kurdish problem on the border. And the West continued to negotiate after Russia engaged in blatant subterfuge and spectacular war crimes, emboldening the scorched earth campaign in Aleppo.

Ambassador Power is right to ask about shame. Ultimately, a great share of it will belong to her government and the other fair-weather “friends of Syria” who supported the country’s revolution only half-heartedly — enough to prolong it while also sealing its failure.

For a quarter-century, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the international order trended toward more accountability and cooperation. Sure, international law is most often honored in the breach, and institutions like the International Criminal Court have no enforcement arm. But for a time, the international community was a meaningful forum with a conscience, and it created new doctrines like the “responsibility to protect,” which held that any state that wantonly murders its citizens forsakes its sovereignty. New norms took root: War crimes still occurred but invited wider and wider condemnation, military interventions required legal justification, and humanitarian concerns achieved the status of core national interests.

Altruism and self-interest were crucially intertwined in doctrines that aimed to make the world a less cruel but also a more stable place. We opposed torture and war crimes elsewhere because they’re dead wrong, but also because we don’t want out own citizens subjected to them.

Today, an opposite calculus is in effect. We don’t stand against the leveling of Aleppo because we reserve the right not to be judged for similar crimes. It will be difficult for America to invoke human rights as a cornerstone of foreign policy.

On a human level, Aleppo’s fall is nearly unbearable. Citizens, volunteer doctors, children, and others are hunted from neighborhood to neighborhood in the city’s shrinking Assad-free patch. Shells and bombs fall indiscriminately. Those who flee risk massacre by pro-government militias. If they make it to safety, they face torture or even death in Assad’s gulag. We can hear their pride and desperation in videos, tweets, and phone calls, often broadcast live as the battle for Aleppo climaxes.

Many of us knew the end was coming, but when it finally did this week, it was a sucker punch to the gut. Even if we expected it, we hoped Aleppo would not finish this way.

While this personalized violence is horrifying, it is hardly unique to Aleppo. Yet this apex of expedient, Machiavellian criminality caps off a long period when norms have eroded and international law has been undermined by its most important sponsors. Everyone has a stake in the erasure of Aleppo — not just the trigger-pulling governments in Damascus, Tehran, and Moscow.

Aleppo has thrived for millennia and one day will recover as a city. The prognosis is not as good for the ideas we have cherished since World War II and which we hoped would prevent any repeats.

Syria’s war will continue for some time — probably years. But barring a major and unexpected global shift, its outcome is no longer in doubt. Assad’s government will stay in power, slowly re-extending its reach over the entire territory of Syria and cobbling together some new version of the terror-and-torture apparatus through which it coerced the compliance of its population until 2011.

We watched the block-by-block incineration of a free city. Its rubble will build the foundation of our century’s pessimistic new world order.

Interview with TCF’s Sam Heller about Damascus trip

Century Foundation fellow Sam Heller returned to Beirut from Syria over the weekend, where he attended a government-backed conference—the first of its kind in years, with Western journalists, analysts and political researchers invited to hear the government’s point of view. He spent a week in Damascus. Century Foundation fellow Thanassis Cambanis talks with Sam about his first impressions.

Thanassis: Welcome back from Syria, Sam. We’re glad to have you back in Beirut. When was the last time you were in Syria prior to this trip?

Sam: I lived in Syria between 2009 and 2010, but I haven’t been back since. I actually left Syria to do a two-year master’s degree in Arabic that would have taken me back to Damascus for its second year—but that was 2011, so that obviously didn’t happen.

Since I turned back full-time to researching Syria in 2013, I’ve devoted most of my time and energy to looking at the Syrian opposition and Syria’s opposition-held areas. What I’ve understood about conditions inside regime-held western Syria, including Damascus, has been filtered through the media or second-hand fragments, from people who travel in and out.

But for all I’ve written about Idlib, I’ve never actually been there. It’s Damascus—and, to a lesser extent, al-Hasakeh in Syria’s east—that reflects my actual, lived experience in Syria. And so it’s good to be back and see the situation in the part of the country I knew best, if only to further ground myself in something real.

Thanassis: What was your first impression on this trip?

Sam: I don’t think this trip necessarily upturned my understanding of conditions inside. But it was useful to see things firsthand and to be able to put some meat on my existing impressions of the functioning of the regime and life in government-held areas.

And this might be shallow, but for me—as an outsider, and as someone who missed the worst years of the war in Damascus in 2013 and 2014—I was struck by how much was the same. The city and the society have obviously been militarized; Damascus is filled with checkpoints and uniformed men. And it seems like everyone, if you ask, has a story of economic hardship, displacement, or the death of friends and family. And yet, even while everything is sort of worse, much of what I knew about Damascus is still there.

Are we all interventionists now?

[Published in War on the Rocks.]

Ever since Russia reneged on an ill-conceived ceasefire plan for Syria in September and participated in a barbarous military campaign in Aleppo, the crescendo of American voices calling for some action in Syria has risen a notch, apparently reaching the White House this week.

Throughout the Syria crisis, the U.S. government bureaucracy and key power centers in the foreign policy elite have espoused Obama’s version of restraint and resignation, toeing a position along the lines of “Syria is a mess, but there’s little we can do.” Lately, though, an escalatory mindset has taken hold, with analysts and politicians floating proposals to defend Syrian civilians and confront an expansionist Russia.

“I advocate today a no-fly zone and safe zones,” Hillary Clinton said in the most recent debate, taking a position starkly more interventionist than the president she served as secretary of state. She continued: “We need some leverage with the Russians, because they are not going to come to the negotiating table for a diplomatic resolution, unless there is some leverage over them.”

Does this kind of talk represent a sea change in decision-making circles? After years of decrying missteps in the ill-begotten wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and debating America’s shrinking footprint, is there now a convergence to once again embrace interventionism among politicians, public opinion and the foreign policy elite that some in the White House derided as “the blob”?

I think there is, and those of us who have espoused a more vigorous intervention in Syria and a more activist response to the Arab uprisings need now to take extra care in the policies we propose. As the pendulum swings back toward a bolder, more assertive American foreign policy, we must eschew simplistic triumphalism and an unfounded assumption that America can determine world events. Otherwise we risk repeating the mistakes of America’s last, disastrous wave of moralism and interventionism after 9/11.

It’s important not to overstate the backlash to Obama’s calls for humility and restraint, and not too ignore the activist and moralistic strains that connect Obama’s foreign policy to that of his predecessors. With those caveats, it seems like we’re on the cusp of a return to a more activist foreign policy.

That doesn’t make us all interventionists yet, but it does expose the United States to renewed risk, making it all the more important to restore some honesty and clarity to the debate. Any discussion about America’s global footprint has to acknowledge that it’s still huge. America has not retrenched or turned its back on the world. Any discussion about Syria has to acknowledge from the get-go that America already is running a billion-dollar military intervention there. So when we talk about escalating or de-escalating, we need to be clear where we’re starting. The United States is heavily implicated in all the Arab world’s wars, with few of its strategic aims yet secured. This unrealized promise has fueled frustration about America’s role.

Even Trump’s isolationist calls to tank the international order and make America great by impoverishing the rest of the world echo, in part, a desire for strength and moral clarity. The likely next president, Hillary Clinton, has steadily stood in the American tradition of liberal internationalism which has been the dominant school of foreign policy thought since World War II. That history embraces an international order dominated by the United States and trending toward market economies, free trade, liberal rights, and a rhetorical commitment to freedom, democracy and human rights, which even in its inconsistent and opportunistic pursuit, has been considered anything from an irritant to a major threat to the world’s autocracies. This ideological package has underwritten America’s best foreign policy, like Cold War containment, and its worst, like the invasion of Iraq and the post-9/11 savaging of the rule of law.

Syria’s war has been the graveyard of the comforting, but vague, idea that America could lead from behind and serve as a global ballast while somehow keeping its paws to itself. Other destabilizing realities helped upend this dream, among them Europe’s financial crisis, the rise of the extreme right, the Arab uprisings, the collapse of the Arab state system and a new wave of wars, unprecedented refugee flows, and the expansionist moves of a belligerent, resurgent Russia.

Pointedly, however, Syria has embodied the failure of the hands-off approach. Its complexity also serves as a warning to anyone eager to oversimplify. Just as it was foolish to pretend that the meltdown of Iraq and Syria, and the rise of the Islamic State, were some kind of local, containable imbroglio, it is also foolish to pretend that a robust, interventionist America can resolve the world’s problems. Neither notion is true.

America is the preeminent world power. It can use its resources to manage conflicts like Syria’s in order to pursue its interests. Success flows from clearly defining those interests and intervening sagely, in a coordinated fashion across the globe. America has played a disproportionate role in designing the international institutions that created a new world order after World War II. For a a time after the end of the Cold War, it enjoyed being alone at the top of the global power pyramid. American influence swelled for many reasons, highest among them American wealth, comprehensible policy goals, and appealing values. But dominance is not the same thing as total control, and a newly assertive U.S. foreign policy still can achieve only limited aims.

The next president will have to recalibrate America’s approach to power projection – how to deter powerful bullies like Russia, how to manage toxic partnerships with allies like Saudi Arabia, how to contain the strategic fallout of wars and state failure in Iraq, Syria, and the world’s ungoverned zones. The most visible test right now is Syria. Syria is important – not least because of the 10 million displaced, the 5-plus million refugees, the half million dead. It is also important as the catalyst of widespread regional collapse in the Arab world, the source of an unprecedented refugee crisis, a hothouse for jihadi groups, and as a test of American resolve.

It’s harder and harder to find foreign policy experts willing, like Steven Simon and Jonathan Stevenson recently did inThe New York Times, to argue that any American effort to steer the course of Syria’s war will only make things worse. (British journalist Jonathan Steele made a similar argument this week in The Guardian that any Western effort to contain war crimes in Aleppo “threatens to engulf us all.”)

Figures from both major U.S. parties have increasingly shifted to arguing that the United States will have to experiment with some form of escalation, because the existing approach just hasn’t worked. Hillary Clinton’s team is apparently considering a range of options including no-fly zones or strikes on Syrian government targets. The ongoing shift is less the result of a revelation about Syria’s meltdown and more a reflection of American domestic politics and a consensus that it’s time to recalibrate America’s geostrategic great power projection.

As this debate gets underway in earnest, it is crucial to force all sides to draw on the same facts, and be honest about the elements of their policy proposals that are guesses. For example: It is a fact that Syria is in free fall and Iraq barely functions as a unitary state, with fragmenting civilian and military authority on all sides of the related conflicts. It is a guess that Russia has escalation dominance and is willing to pursue all options, including nuclear conflict, if the United States intervenes more forcefully in Syria. It is a fact that tensions between the United States and Russia are at a post-Cold War high. It is a guess that they will clash directly over Syria rather than Kaliningrad or Ukraine or some other matter. It is a fact that the rise of the Islamic State and the flow of millions of displaced Syrians has destabilized the entire Middle East and reshaped politics in Europe. It is a guess that if the United States shoots down some of Bashar al-Assad’s helicopters it will lead to more fruitful political negotiations among Syrian factions and their foreign sponsors.