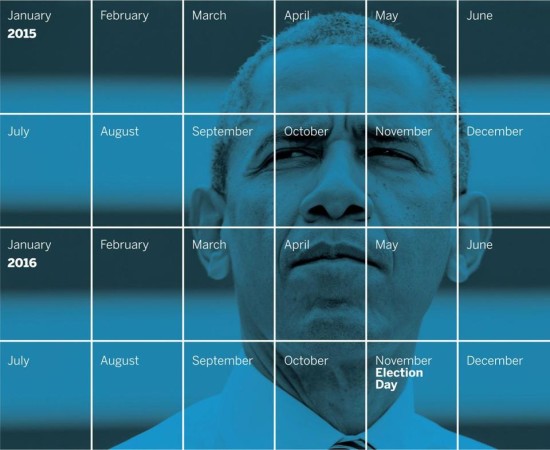

Foreign policy wins Obama still can pull off

JACQUELYN MARTIN/AP;

GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.

LAST MONTH, in a pre-Christmas surprise, the White House announced a major foreign policy breakthrough on a front that almost nobody was watching: Cuba and the United States were ending nearly a half century of hostility, after secret negotiations authorized by the president and undertaken with help from the pope. Lately, America’s zigzagging on the grinding war in Syria and Iraq has attracted the most attention, but President Obama has punctuated his six years in power with a series of foreign policy flourishes, among them ending the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; launching an international military intervention in Libya; and a “reset” with Russia, which ultimately failed.

Time is running short. Obama has only two more years in office, and an oppositional Congress that will likely block any major domestic policy initiatives. But the president’s opening with Cuba raises a question. What other foreign-policy rabbits might this lame-duck president try to pull out of his hat?

Obama often talks about the arc of his history and his legacy. And we know from history that presidents in the sunset of their terms often turn their focus to foreign policy, where they have a freer hand. The presidential drift abroad has been even more pronounced in administrations that face an opposition Congress and limited support for any ambitious domestic agenda items.

Despite keeping his promises to end two wars and to reestablish America’s power to persuade, not just coerce, Obama has drawn some scorn as a foreign policy president. Poobahs across the spectrum from right to left have derided him for not having a policy (drifting on Syria, passively responding to the Arab Spring), for naively pursuing diplomacy (the reset with Russia, the pivot to Asia), for adopting his predecessor’s militarism (the surge in Afghanistan, the war on ISIS).

But, free from any future elections, the president may finally be at liberty to engineer bigger symbolic moves, like the recent rapprochement with Cuba. He can even try for politically unpopular policy realignments that would ultimately benefit his successor.

So what bold gambits might Obama reach for in his final two years? We’re talking here about unlikely developments, but ones that, with a push from a willing White House, could actually happen. Here’s a look at what might be on Obama’s wish list, and his real chances of grabbing any of these wonky Holy Grails.

A stand on torture

IN ITS WAR ON TERROR, America adopted a number of tactics that its leaders used to call un-American. Some of them appear here to stay, like remote-control bombing runs by robot planes (known by the anodyne moniker “drone strikes”), which have killed more than 2,400 people and have become the most common way Obama pursues suspected militants in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen.

But other tactics have lingered long after the White House has concluded they are counterproductive: most notably the use of torture, and the indefinite detention of enemies without charge or trial in the limbo prison at Guantanamo Bay. President George W. Bush, toward the end of his term, backtracked on both policies, quietly roping in the use of torture and exploring ways to shut down Gitmo. Obama has taken a more assertive moral stance on the issue, perhaps because he realized that America’s treatment of detainees delivered a propaganda boon to its enemies—and increased the risk of similar mistreatment for American detainees. But though he ended torture, he hasn’t settled the political debate, nor has he managed to close Guantanamo Bay.

This is one problem that Obama could resolve by fiat, if he were willing to deal with the inevitable political yelps. He could close Guantanamo Bay overnight, sending dangerous detainees to face trial in the United States, shipping others to allied states like Saudi Arabia, and releasing the rest (many of whom have spent more than a decade incarcerated). To those who would accuse him of putting America at risk by not detaining accused terrorists without charge forever, Obama could point to the US Constitution and shrug his shoulders. As for torture, some believe the best move would be to follow the South African model of a truth commission that airs all the grisly details, while granting immunity from prosecution to those who testify. Of course, critics of torture would decry the amnesty, and supporters would decry the release of narrative details.

Harvard political scientist Stephen Walt says to forget the truth commission. The simplest way for Obama to end one of the most contentious debates in America, he argues, is with a set of sweeping pardons for all those involved in torture. That could include officials from Bush on down, as well as leakers like Chelsea Manning. In an e-mail, Walt said such a move would be a “game changer,” although one with odds so long that he put it in the category of “foreign policy black swans.” “I regard it as very, very unlikely, but it would be a huge step,” he said.

Presidential pardons could make clear that torture and extrajudicial detention were illegal mistakes, while simultaneously freeing whistle-blowers and closing the books on the whole affair. Obama could even wait until after the 2016 presidential election has been decided, altogether eliminating political risk.

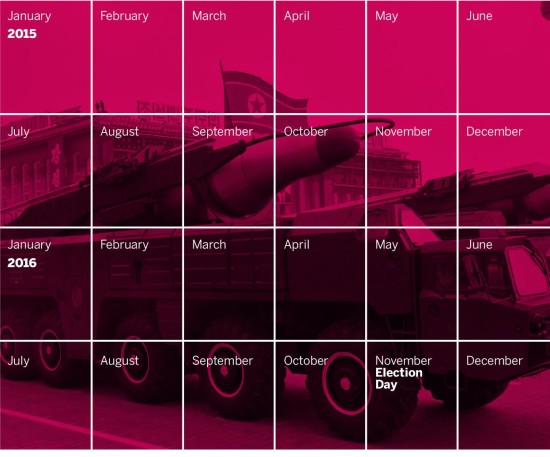

A détente with North Korea

EPA/KCNA ; GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

NORTH KOREA entered the news recently because of its alleged role in the Sony hack over the silly film “The Interview.” But the hermit kingdom isn’t a problem because of its leader Kim Jong-un’s absurd cult of personality. No, North Korea poses a problem because it’s a belligerent, opaque, hyper-militarized state that stands outside the international system and is armed with serious rockets, nuclear warheads, and a powerful military.

One fraught area remains the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. About 30,000 American personnel are deployed there, and North Korea routinely provokes deadly clashes to remind the world of its resolve.

If Obama could finally end the Korean war—officially just in a cease-fire since 1953—he would resolve the most dangerous flashpoint in Asia and perhaps the world. Kim Jong-un, like his father and grandfather, has an almost mythic status among villainous world leaders. Millions have suffered in North Korea’s prison camps, and the militarized state maintains a hysterical level of propaganda that makes it stand out even among other “rogue” states. Even China, long the dynasty’s primary backer, has begun to express irritation with North Korean’s volatility.

But all this creates an opportunity, according to veteran Korea watchers. “There’s an opportunity, oddly enough,” says Barbara Demick, author of “Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea.” “It would require a bold gesture on somebody’s part.”

Kim Jong-un, third in the family dynasty, has lived abroad and appears more open-minded than his father, Demick says. More importantly, despite the anti-American rhetoric, North Korea might want to end its comparatively young feud with the United States, which dates only to the 1950s, to better protect itself from the local threat from its millennial rival China.

Earlier efforts at reconciliation in the early 1990s foundered and collapsed after Kim Jong-il cheated on an agreement to freeze his nuclear weapons program. Demick and other experts are more hopeful that his son will be more interested in negotiating. Three years after taking over, Kim Jong-un seems to have consolidated power. He has relaxed some control over private trade, and he executed a senior member of his own regime who was considered China’s man in Pyongyang, asserting himself over rivals within his family and government.

“Unlike his father, Kim Jong-un doesn’t seem to want to spend his whole life as the head of a pariah state,” Demick says.

It’s quite difficult to imagine North Korea doing an about face and becoming a friendly US ally in Asia, but surprising things have happened. Vietnam, just a few decades after its horrifying war with the United States, is now as warm to Washington as it is to Beijing. Obama could try to end one of the world’s longest lingering hot wars by forging a peace treaty with Pyongyang.

A grand bargain with Iran

AMERICA’S RELATIONSHIP with Iran never recovered from the trauma of the US embassy takeover and hostage crisis of 1980. Iran, flush with oil cash and the messianic fervor of Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolution, has been at the center of regional events ever since. Iran has been perhaps the most influential force in the Arab world, helping to form Hezbollah, prop up the Assad dictatorship in Syria, and foiling America’s plans in Iraq.

Of late, attention has focused on negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, but that’s arguably not the most problematic aspect of Iran’s power in the region. A regional proxy war between two Islamic theocracies awash in petrodollars—Shia Iran and Sunni Iraq—has contaminated the entire Arab world. Resolving Iran’s major grievances and reintegrating it into the regional security architecture would reduce tensions in several ongoing hot wars and dramatically reduce risks across the board.

Obama could seek an overall deal with Iran, in which Tehran and its Arab rivals would agree to separate spheres of influence in the region and the United States could reopen its embassy. A Tehran-Riyadh-Washington accord could signal a major realignment in the region and a move toward a more stable state order, and is actually possible—not likely, but possible.

The big protagonists here, Iran and Saudi Arabia, lose a lot of money in their proxy fighting. It’s been 35 years since the 1979 Iranian revolution that brought the ayatollahs to power, and both sides—Riyadh’s Sunni theocrats and Tehran’s Shia ones—have learned that no matter what human and financial resources they pour in, they can’t achieve regional hegemony. Eventually, they’re going to have to coexist. Israel, meanwhile, has maintained a fever pitch about Iran, and should welcome a calming shift.

The trick for today’s White House is what’s going on internally in Iran. “My sense is that if Obama and Kerry could push a button and normalize relations with Iran they’d do so in a heartbeat,” says Karim Sadjadpour, who studies Iran at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The biggest obstacle to normalization is not in Washington, it’s in Tehran. When your official slogan for 35 years is ‘Death to America,’ it’s not easy to make such a fundamental shift.” But if Iran’s president can find a way to de-fang the hard-liners in his own country, Sadjadpour believes, there’d be a strong constituency among the political elites in Iran and the United States for a grand bargain.

A step back from Israel

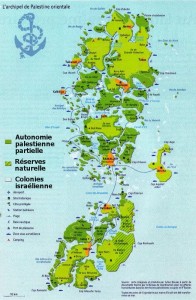

PRESIDENT AFTER presidenthas poured time and energy into a Middle East peace process that never works. Failures have cost America political prestige around the world. As more governments lose patience with the continuing Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory, America has found itself defending the Israeli government at the United Nations even as the same Israeli government openly mocks Washington’s agenda.

The bold move that the president could make—potentially changing the parameters of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—would be not to invest more in some new variant of the peace process, but simply to care less. Cooling our relations with the Israeli government could reestablish the strategic calculations at the core of the relationship and remove the distracting secondary issues that have accumulated around it. Israel is one of America’s closest military and economic allies, and the tightly woven relationship will survive a political shift. Obama could simply announce that the United States would no longer act as Israel’s main international political advocate, and that we would be happy to let other actors try to negotiate agreements, as the Norwegians did in the early 1990s.

Such a move would not resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but it would go a long way toward reducing costs for the United States. Washington doesn’t need to own the baggage of its close allies. It could treat Israel like it treats the United Kingdom: as a special ally with extra privileges, but one whose bilateral conflicts are its own business.

“I realize that a president’s hands are tied by Congress when it comes to Israel, but there is plenty that the president can do without congressional approval,” says Diana Buttu, a lawyer and former adviser to the Palestinian Authority. She said that Obama has plenty of options, from using his bully pulpit to condemn Israeli actions to not blocking Palestinian UN resolutions.

Duke political scientist Bruce Jentleson suggests another kind of US surprise: incorporating Hamas into peace talks. “A delicate dance no matter what,” he wrote in an e-mail. “But Middle East peace breakthroughs have usually been through the unexpected,” like Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s trip to Jerusalem, or the secretly negotiated Oslo Accords.

What Jentleson says of Middle East breakthroughs may well be true of other ones as well. Global politics never loses its capacity to catch us off guard, regularly delivering events that experts say are impossible. Only an inveterate optimist would bet money on any of these slim possibilities coming to pass. But only a fool would be certain that they won’t.

Where Hamas Goes From Here

Ismail Haniya delivers a speech after the conflict in Gaza. (Ahmed Zakot / Courtesy Reuters)

[Originally published in Foreign Affairs.]

Once again, Hamas has been spared from making the difficult political choice that face most resistance movements when they gain power: whether to focus on the fight or to govern. Since it won the Palestinian elections in 2006 and then took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, Hamas has been free to pursue a middle course, resisting Israel while blaming its political failures on its cold war with Fatah and on Israel’s blockade. Now Hamas will tout the concessions it won from Israel last week — as part of the ceasefire, Israel agreed to open the border crossings to Gaza, suspend its military operations there, and end targeted killings — as proof that it should not give up fighting. Meanwhile, the outcome should be enough to buy Hamas cover for its poor record of governance and allow it to again defer making tough choices about statehood, negotiations, regional alliances, and military strategy. The group might even be able to use the momentum to supplant Fatah in the West Bank as it has done in Gaza.

Hamas’ recent advance won’t fully mask the organization’s central dilemma, nor will it cover internal rifts about how to solve it. In the American and Israeli media, portrayals of Hamas often focus heavily on the group’s commitment to eliminating the Jewish state. And certainly any fair study of the group should take into account that goal. Yet for Hamas, the end of Israel is more an ideological starting point than a practical program. And what comes after the starting point is unclear: Hamas has never developed a vision of what a resolution short of total victory might look like, nor has it spelled out an agenda for governing its own constituents, despite all these years in power. In part, that is because Hamas is a diffuse and contested movement, whose competing factions all work toward their own self-interest.

Hamas’ top political leadership used to operate out of Damascus but scattered to Cairo, Doha, and other Middle Eastern capitals this year as Syria descended into chaos. Since then, the exiled leadership has clashed publicly with Hamas’ Gaza-based leadership. Khaled Meshal, the organization’s main leader, now based Doha, and his cohort have generally allied with the Sunni Arab states over Iran, welcoming the rise of Islamists in Egypt, in Tunisia, and among the Syrian rebels. Meshal himself has publicly endorsed a truce with Israel based on Israel’s withdrawal to its 1967 borders. The rest of the exile-based leaders have also indicated their willingness to consider a truce, although they say they would consider the deal temporary and would not recognize Israel. Party in response to Hamas’ pragmatism, and partly in acceptance of the reality of the movement’s rising power. Arab leaders finally ended their informal boycott of Gaza, and, in recent months, the emir of Qatar and the prime minister of Egypt paid visits.

Yet the growing stature of Hamas might accentuate, rather than diffuse, the tensions between its exiled chiefs and its Gaza-based leadership. According to Mark Perry, a historian who follows Palestinian politics, Hamas’ prime minister, Ismail Haniya, has endorsed a close relationship with Iran. For his part, Haniya paid a warm visit to Tehran in February, provoking the ire of Arab leaders, who have since given him the cold shoulder, preferring instead to meet with other Hamas leaders. Haniya has expressed no interest in talking about a two state solution and overall, the rest of the Gaza-based leadership has simply grown more uncompromising under the Israeli blockade and now two lopsided wars. It prefers full-throated resistance to any political settlement.

It is unclear whether the differences presage an ideological split or are simply the result of two very different vantage points: inside Gaza, where the leaders have to worry about staying in power, and outside it, where the leaders worry about staying regionally relevant. So far, Hamas has seemed unable to address the issues that divide the two factions, which might explain why the movement has not selected a successor to Meshal, who was supposed to step down this spring. The sides do, of course, have lowest common denominators that hold them together: resistance as the primary avenue to winning Palestinian rights; gaining greater share of Palestinian leadership; and Islamism.

Since Hamas’ creation in 1987, it has tried to match Fatah’s strength. With that goal largely accomplished by 2007, it has moved on to pushing Fatah completely to the sidelines by maintaining a commitment to Islamism and opposition to the Jewish state. By contrast, Fatah has remained secular, and has even agreed to recognize Israel and to conduct an experiment in joint governance with it through the Palestinian Authority. Two decades into the Oslo process, Fatah has little to show for its efforts. Meanwhile, Hamas has not had to face Palestinian voters since 2006. Polling suggests that Palestinians — Gazans in particular — have lost patience with Hamas. But each conflict with Israel gives the movement a new lease on life.

As recently as last week, Israel was describing in breathless terms the latest tepid exploits of the smoky, aging leader of Fatah, Mahmoud Abbas, who is on the verge of obtaining non-member observer status at the United Nations. Israel’s foreign ministry was reportedly circulating policy options to deal with his gambit that included dismantling the Palestinian Authority and withholding its rightful tax revenues, which would effectively subject the West Bank to the same kind of isolation that Gaza has faced since Hamas took power. That would play directly to the long-term goals shared by Hamas’ leaders in Gaza as well as those in exile: to take over from Fatah the role of primary representative of all Palestinians.

What is more, developments in the region have boosted Hamas’ position. This is not the Middle East of the last war, in 2008-09, when, for the most part, the Arab world stood by as Israel subjected Gaza to overwhelming and disproportionate bombing. That conflict killed 1,387 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. Hosni Mubarak’s government in Cairo even assisted the Israeli campaign against Hamas, while the West and Arab world poured money into Fatah’s West Bank government as a counterweight to Hamas. The regional landscape now is entirely different.

Still, despite a warm rhetorical embrace for Hamas, the Egyptian state has yet to significantly change its policy. It hasn’t opened the border with Gaza, nor does it want to do anything that would allow Israel to shift responsibility for Gaza to Egypt. Throughout the cease-fire negotiations, Israel said Egypt would be responsible for keeping the peace. But no matter what Israel says now, the language of the agreement and the reality on the ground make clear that Israel struck a deal with Hamas at Egypt’s insistence, and that Egypt will certainly be no guarantor of Hamas’ behavior. That’s an achievement for the ruling Muslim Brotherhood. As its (and Egypt’s) influence grows, it might be able to promote its preferred exiled Hamas leaders at the expense of the more uncompromising ones in Gaza.

Hamas has other competitors to worry about now. Until the uprisings two years ago, the Middle East’s Islamist movements were mostly on the outside looking in, railing against secular nationalist despots. In fact, Hamas and Hezbollah were the only Islamist movements who could claim to have ascended to power through popular victories at the ballot box. In the pre-uprising Arab world, then, Hamas (like Hezbollah) could plausibly claim some leadership of a regional Islamist movement. No more. The Muslim Brotherhood now governs Egypt. Islamists were elected to power in Tunisia. They have also emerged as power centers in Libya and among the Syrian opposition. Now that Islamists are competing for power in large states, Hamas (and Hezbollah) could shrink to their proper size in terms of influence. This outcome seems even more likely now that Hamas faces a vibrant challenge from jihadi fundamentalists within Gaza who consider Hamas far too moderate.

Hamas has presented itself as a voice for resistance, but as Gaza tries to rebuild and recover from this latest war, the organization will have to grapple with its own authoritarian, corrupt record in power. Its exiled leaders might sound more reasonable to Western ears, but they’re not the ones who actually control territory and manage a government. If it gets what it wants — a central role in Palestinian leadership — Hamas will have to reconcile its own internal factions or else risk a split. On the quickly changing ground of the new Arab politics, Hamas, like other governing movements, will have to articulate an ever-more detailed, constructive program, to convince rather than compel its constituents.

Hulk in the the Holy Land

My friend Brian Katulis has written perhaps the most penetrating short meditation on Israel-Palestine published in quite some time — a historical look at the long conflict through the eyes of the pre-Oslo Incredible Hulk.

My friend Brian Katulis has written perhaps the most penetrating short meditation on Israel-Palestine published in quite some time — a historical look at the long conflict through the eyes of the pre-Oslo Incredible Hulk.

In “Power and Peril in the Promised Land,” Bruce Banner stows away on a ship and wakes up in Israel, where he befriends a young Arab boy who is killed by Arab terrorists. This angers Bruce, who turns into the Incredible Hulk and takes the boy’s body next door to Jordan, all the while chased by the Israeli super heroine Sabra.

One can imagine Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, George Mitchell or even President Obama sympathizing with the Hulk’s frustration found on the last page: “Boy died because boy’s people and yours both want to own land! Boy died because you wouldn’t share.”

Priceless. And timeless.

If War Comes, Indeed

More than a month after skimming it, I have had the time to carefully read Jeffrey White’s paper on what a new war between Hezbollah and Israel might look like. “If War Comes: Israel vs. Hizballah and Its Allies,” a Washington Institute for Near East Policy publication, contains reams of useful information about the military tactics that parties to another Lebanon war might employ. However, White builds his argument on some misunderstandings and highly debatable assumptions about actors other than Israel. His analysis ignores much of the history of Israel’s last 30 years of war. And it fails to imagine any of the creative measures Hezbollah and its allies might take in another conflict.

More than a month after skimming it, I have had the time to carefully read Jeffrey White’s paper on what a new war between Hezbollah and Israel might look like. “If War Comes: Israel vs. Hizballah and Its Allies,” a Washington Institute for Near East Policy publication, contains reams of useful information about the military tactics that parties to another Lebanon war might employ. However, White builds his argument on some misunderstandings and highly debatable assumptions about actors other than Israel. His analysis ignores much of the history of Israel’s last 30 years of war. And it fails to imagine any of the creative measures Hezbollah and its allies might take in another conflict.

White’s main arguments are:

- Israel and Hezbollah both want a rematch from the inconclusive 2006 war.

- The next time around the stakes will be higher: both sides will fight for a decisive result.

- Hezbollah’s relationships with Syria and Iran make it more likely that a conflict will escalate into a regional conflagration.

- At its conclusion, White argues, a devastating Israel-Hezbollah war could create major new political crises, leave Israel occupying some of Lebanon and possibly all of Gaza, and destroy extensive civilian infrastructure – but he says it might also “break” Hezbollah military, weaken the Syrian regime, limit Iran’s influence, and weaken Hamas.

It’s definitely worth reading, and Andrew Exum posted his own very perceptive response to the paper on his blog. I want to amplify some similar questions and criticisms.

Fundamentally, White doesn’t account for the political reality of Lebanon today: Hezbollah has won the support of 1 million or more Lebanese, and achieved a statistical tie in the last elections. As a result, Hezbollah controls one-third of the government ministries, enjoys warm collegial relations with the president, the Lebanese Army, and much of the state’s institutions, and holds not only veto power but provides counsel to the weak government helmed by Saad Hariri.

Furthermore, Hezbollah has effectively silenced those forces in Lebanon that question Hezbollah’s right to manage its own militia, independent from the government’s army. Any attack by Israel on Lebanon – especially one that involveds widespread bombing of civilian infrastructure in particular in areas populated by Lebanese who oppose Hezbollah – will only renew Hezbollah’s legitimacy and expand its dominance over Lebanese politics.

There is simply no outcome of a war that, as White imagines, could leave Hezbollah “broken as a military factor in Lebanon and weakened politically.” (To “break” Hezbollah would require Iran and Syria to end their partnerships with it.) Hezbollah’s military prowess depends on a few thousand fighters and relatively low-tech armaments that Iran and Syria can resupply at little cost. Hezbollah’s staying power stems from the web of influence it has built with its militia, its politicians, its network of social and educational institutions, and its increasingly potent ideology of Islamic Resistance.

There is simply no outcome of a war that, as White imagines, could leave Hezbollah “broken as a military factor in Lebanon and weakened politically.” (To “break” Hezbollah would require Iran and Syria to end their partnerships with it.) Hezbollah’s military prowess depends on a few thousand fighters and relatively low-tech armaments that Iran and Syria can resupply at little cost. Hezbollah’s staying power stems from the web of influence it has built with its militia, its politicians, its network of social and educational institutions, and its increasingly potent ideology of Islamic Resistance.

In passing, White invokes other assumptions that at best raise enormous questions and problems:

- He suggests that after another war Israel will occupy part of Lebanon and perhaps all of Gaza. Israel’s troubling experience doing so in the past led it to unilaterally withdraw from Lebanon in 2000 and Gaza in 2006. What does White think has changed to make occupation of these areas more sustainable or effective for Israel?

- In 2006, Israel thought that holding all of Lebanon accountable for the behavior of Hezbollah would weaken Hezbollah and strengthen its opponents. The opposite happened, and Hezbollah emerged stronger than ever before. Why would the same course of action by Israel this time produce different political results?

- The case for an expanded war depends on a calculus that Hamas, Syria and Iran might be drawn into a war, directly, if they believe Hezbollah is losing. An alternate interpretation suggests that none of those actors would have an incentive to directly involve themselves in an Israel-Lebanon war, especially if they believe that Hezbollah wins politically no matter what the outcome on the battlefield. (In my estimation, a Hezbollah that resists and survives to fight again wins politically even if its military forces are decimated.) The behavior of the “Axis of Resistance” parties in Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009), the 2006 Lebanon war, and previous crises, suggests they see no need for overt involvement in a time of hot war in order to cash in on the political benefits of being allies afterward.

- What of Israel’s cost in diplomatic support and strained relations if it engages in the kind of speedy and widespread campaign White describes? “War on this scale may come as a chock to some of Israel’s supporters, and to countries and organizations under the spell of ‘proportionality,’” he writes. Indeed, such a war could cost Israel vital support domestically, and in the United States, not to mention bringing it approbation and possible legal action supported by parties “under the spell of ‘proportionality,’” like the United Nations and the United States, whose military hews to that principle in its own laws of war.

- Iran and Syria gain from Hezbollah’s willingness to fight Israel, and its presumed survival of such a conflict. They have little to gain from a frontal military confrontation with Israel, and would likely be content to sit on the sidelines, frustrating any attempt to expand a war and fulfill the almost Polyanna-ish hopes to “reorder” regional politics, critically weaken all of Israel’s enemies in a single war, and “shatter” Hezbollah’s “myth of resistance and military power.”

There are lots of other questions worth asking, including whether analysts should take Israel’s war in Gaza as a fair preview of a conflict with a major opponent like Hezbollah.

Andrew Exum very graciously questioned White’s assumptions in his response to the paper at WINEP in September, and pointed out that the entire exercise seems to concentrate on the minutia of military tactics at the expense of examining the overall political and strategic context.

The analysis betrays a common Achilles Heel I’ve encountered while reporting on the Middle East – a real lack of familiarity with the governments, militant movements, and public sentiments in Arab states and in Iran. Many Hezbollah supporters I interview read Haaretz on line, study Hebrew, and read books like Ariel Sharon’s autobiography. They might not understand Israel and Israeli society, but they try, and their attempts at self-education have translated into adaptive tactics and strategy. Meanwhile, supporters of Israel all too often forget to question their own assumptions, make critical assessments of Israel’s enemies, or update those assessments as those enemies evolve. As a result, they can fall into analytical traps, misapprehending the motives of their opponents, their levels of public support, and the likely political consequences of applying military force to them.

If I understand White correctly, he’s arguing that next time Israel goes to war on its northern border, Israel should apply lethal, overwhelming, widespread military force to Lebanon, and it should be prepared to simultaneously do so to Gaza, Syria, and Iran. Such a venture, White argues, would probably leave Israel in a stronger position.

Reality, and the experience of Israel’s last wars, suggests the opposite. Widespread conflict would probably not leave Israel more secure, and would at the same time unleash manifold waves of unintended consequences. As the United States learned from its venture in Iraq, upending the card table doesn’t necessarily lead to better hands in the next game.

Jeffrey White hasn’t provided any compelling reasons why Israel would emerge in dramatically better condition than it is in today after a massive war against Lebanon, Syria, Gaza and Iran, and he certainly hasn’t provided any evidence (historical, comparative, analytical) that war in 2011 would play out differently than it did for Israel in 2009, 2006, 2000, 1996, 1993, and 1982.

He has, however, given us a glimpse of the kind of pie-in-the-sky assumptions needed to convince an American audience that a high-risk, expeditionary, regional war might yield great, unspecified consequences – without accounting for the chilling risks such a war carries for millions of Arabs, Israelis, and for U.S. interests in the Middle East.

Pointless peace process?

Writing today in The Daily Beast, I ask why Washington appears to invest so much hope in the latest direct talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. People I talked to in the Middle East as these talks were getting underway were almost universally resigned in advance to failure on this round.

Writing today in The Daily Beast, I ask why Washington appears to invest so much hope in the latest direct talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. People I talked to in the Middle East as these talks were getting underway were almost universally resigned in advance to failure on this round.

Two suggestions diplomats and observers in the region made: bring actors like Hamas and the Israeli opposition into the talks, and change the structural incentives for Israel and Palestinian parties, which currently reward the status quo.

Not a single person I interviewed in the Middle East during the last two months expected anything to come of the current talks—certainly not anything good—although, for the record, no one predicted either that a failed peace process would unleash a new intifada or wholesale change in Israeli priorities.

Instead, the Arab diplomats, analysts, and activists who support Hamas and Hezbollah with whom I spoke seemed in accord that for the time being, neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians saw anything to gain from dialogue, except for earning chits with Washington.

The main benefit of a peace process, in this view, is that Washington wants one, and so long as it doesn’t cost anything, Washington’s allies in Ramallah and Jerusalem are happy to oblige.

Iran on Israel’s border

For as long as I’ve been covering this region, there have been some Israeli officials who describe Hezbollah as a crack division of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and conclude that Iran has literally surrounded Israel.

In the war of rhetoric and symbols, Iran appears only too happy to oblige.

This weekend I visited “Iran Park” in Maroun Al Ras, the Lebanese border village where one of the first and nastiest engagements of the 2006 war was fought. Israeli ground troops got bogged down for days on the ridge at Maroun, and Hezbollah fighters consider it one of their finer engagements of the war.

The Iranian government has funded and designed a lush park near the site of the battle, on the mountainside directly overlooking Israel. In the parking, visitors can stand at an observation point beside an Iranian flag fluttering in the wind, and look directly down at the Israeli hamlets of Avivim and Yir’on.

The Iranian government has funded and designed a lush park near the site of the battle, on the mountainside directly overlooking Israel. In the parking, visitors can stand at an observation point beside an Iranian flag fluttering in the wind, and look directly down at the Israeli hamlets of Avivim and Yir’on.

Through an arcade of ponsiana trees and an arch, past a commemorative plaque crediting President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad with gifting the park to the Lebanese, visitors find terraced playgrounds and picnic spots refreshed with the mountain breeze.

There’s soft-serve ice-cream trucks, grills, and replica of the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem – naturally, topped with an Iranian flag as well. Presumably, Israelis down in the valley can look up and see the Iranian flags and the replica Jerusalem mosque.

Along the path, detailed placards provided educational information about Iran – its population, its provinces, the neighborhoods of Tehran, and so on.

On Sunday mourning the park was already nearly full by 10 a.m. with families that had come to enjoy the cooler temperatures of Jabal Amal.

Three families from the humid coast had assembled under one of the palm-frond roof picnic stations, setting in for a long day grilling and eating.

“Coffee?” said Jihan Muselmani, 35.

“We come here for the clean air,” said Najua Khanafer, 52. “We thank all those who work for our land. Sayed Hassan, Iran, Qatar.”

“This will be the first place the Israelis destroy during the next war,” said Jihan.

“Even if they destroy it, we will build it up again,” said Rabab Haidar, 28.

“If you won’t have coffee, you must at least try these apples,” Jihan insisted, clutching a plastic tub of tiny green fruit. “They come from our own tree.”

Terrorist Talkers

It’s a banner day for the topic I’ve been researching all spring : What tools beyond direct force can Western government use to engage, modulate or otherwise shape the behavior of listed terrorist groups? I’ve been studying in particular the use of intelligence community contacts, diplomacy, creative government engagement through aid and trade, and Track Two diplomacy (which we might as well call secret negotiations, since almost all of the important initiatives take place with the full knowledge of the governments involved).

It’s a banner day for the topic I’ve been researching all spring : What tools beyond direct force can Western government use to engage, modulate or otherwise shape the behavior of listed terrorist groups? I’ve been studying in particular the use of intelligence community contacts, diplomacy, creative government engagement through aid and trade, and Track Two diplomacy (which we might as well call secret negotiations, since almost all of the important initiatives take place with the full knowledge of the governments involved).

In the wake of last week’s Supreme Court ruling on the material support statute, which holds that political advice amounts to assistance for terrorist groups, several advocates of off-line diplomacy have reiterated their arguments for engagement.

First comes Mark Perry, author of the book Talking to Terrorists published earlier this year. He argues that the United States, Europe and Israel gain nothing by boycotting groups like Hamas and Hezbollah, because those groups are here to stay and represent large and growing constituencies. Perry broke the story in March that General David Petraeus had told the White House that America’s pro-Israel stance was harming core national interests in the Islamic world. Now, he’s gotten his hands on another CentCom document in which he reports that some military propose that Hamas should be integrated into the Palestinian Authority security forces and Hezbollah into the Lebanese Army. Both groups, the authors of the military memo argue, should receive American military training, even though they’re defined as foreign terrorist organizations by the U.S. government. (The officers were on a so-called “Red Team” tasked with challenging assumptions and considering alternative ideas.)

The CENTCOM team directly repudiates Israel’s publicly stated view — that the two movements [Hamas and Hezbollah] are incapable of change and must be confronted with force. The report says that “failing to recognize their separate grievances and objectives will result in continued failure in moderating their behavior.”

Meanwhile, on the op-ed page of The New York Times today, the academics Scott Atran and Robert Axelrod write that informal diplomacy has played a crucial role in convincing terrorist groups to renounce violence and enter politics. They cite historical Track Two negotiations begun by private citizens in the transformation of the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Real Irish Republican Army. They also cite their own back-channel conversations with Palestinian militant groups, including Hamas and Islamic Jihad, which they said have yielded important insights.

Private citizens can talk to leaders who are off limits to policy-makers, and can report their findings; in this instance, Atran and Axelrod write, Islamic Jihad reveals itself as recalcitrant and committed to fighting Israel, whereas a Hamas leader suggested he would consider not just a truce (hudna) but peace (salaam). Atran and Axelrod caution that off-line private diplomacy requires expertise and discretion: “Accuracy requires both skill in listening and exploring, some degree of cultural understanding and, wherever possible, the intellectual distance that scientific data and research afford.”

It’s an uncomfortable truth, but direct interaction with terrorist groups is sometimes indispensable. And even if it turns out that negotiation gets us nowhere with a particular group, talking and listening can help us to better understand why the group wants to fight us, so that we may better fight it. Congress should clarify its counterterrorism laws with an understanding that hindering all informed interaction with terrorist groups will harm both our national security and the prospects for peace in the world’s seemingly intractable conflicts.

Advocates of such talks usually take care not to oversell their potential, given that talking to terrorists rarely yields quick results and frequently yields none at all, except for political fallout when secret talks are leaked. All three of these authors have written publicly about their private conversations with leaders of listed terrorist groups. Their conversations were conceived as part of a concerted effort to convince the groups in question to renounce terrorism and violence and pursue their grievances in a legitimate political forum.

It’s unclear whether the Supreme Court ruling would affect these freelance diplomats, who tend to report their foreign terrorist contacts to the government and conduct their diplomatic experiments more or less with their government’s blessing. But for now American law – and grand strategy – have perhaps intentionally left in a fuzzily defined gray area the question of what kind of engagement best complements national counter-terrorism efforts.

Hezbollah’s Flotilla?

Is Hezbollah outfitting blockade-busters to send to Gaza? It appears not, despite some breathless innuendo put forth by an Israeli think tank with close ties to Israel’s intelligence community.

Is Hezbollah outfitting blockade-busters to send to Gaza? It appears not, despite some breathless innuendo put forth by an Israeli think tank with close ties to Israel’s intelligence community.

The Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center in Israel put out a report on June 22 entitled “The aid flotilla planned to set sail from Lebanon is supported by Syria and Hezbollah.” The detailed analysis compiles lots of details about the organizers of two Lebanese boats that plan to sail to Gaza in defiance of Israel’s blockade. One of the organizers, Yasser Qashlak, appears in a clip on Hezbollah’s Al-Manar television network spewing racism:

A day will come when the ships will carry the remainder of the European garbage which came to my homeland [i.e., Israel] and return them to their homelands.

When it comes to the money point so boldly proclaimed in the headline, the Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center quite reasonably concedes (albeit far down, in paragraphs 15 and 16 of a 17-paragraph report) that it found no evidence to substantiate the claim that Hezbollah and Syria are behind the Nagi al-Ali and the all-woman-crewed Maryam.

Hezbollah is careful not to publicly affiliate itself with the Lebanese flotilla, out of fear of complications with Israel. Another reason is the understanding that it will harm their ability to represent the flotilla as reflecting a human rights effort. In response to many articles in the media, Hezbollah issued an explicit denial of its involvement. … The organizers of the ships repeatedly state in interviews with the media that they have no connections with Hezbollah.

That didn’t stop the Israel Defense Forces from trumpeting the report on its news page with the headline “Report: Hezbollah and Syria are organizing the Lebanese flotilla.”

Meanwhile the Lebanese flotilla organizers are finishing the process of getting clearance from the Lebanese government, which wants to stay as far away as it can from provoking Israel. The ships won’t fly the Lebanese flag, and they will sail first to Cyprus and only then to Gaza.

Lebanon and Israel officially remain in a state of war after signing a ceasefire in 1948. While Hezbollah – which is doctrinally committed to the destruction of Israel – dominates Lebanese politics, the government officially is under the leadership of Western-allied Prime Minister Saad Hariri, although one-third of its cabinet members come from Hezbollah and its coalition partners.

Hezbollah (like Hamas) has riled up its base about the Gaza blockade and the deaths of nine people aboard the Turkish ship that tried to bust it. The deadly episode on May 31 fit neatly into Hezbollah’s narratives about Islamic Resistance about “the Zionist entity.” Not least, Hezbollah cashed in rhetorically on the fact that religious Islamists fought Israeli commandos, thereby provoking a policy revision a few weeks later – the first relaxing of the blockade, and in the worldview of Hezbollah and Hamas, an achievement for Islamists on an issue on which secular Palestinians had failed to force any change.

Hezbollah (like Hamas) has riled up its base about the Gaza blockade and the deaths of nine people aboard the Turkish ship that tried to bust it. The deadly episode on May 31 fit neatly into Hezbollah’s narratives about Islamic Resistance about “the Zionist entity.” Not least, Hezbollah cashed in rhetorically on the fact that religious Islamists fought Israeli commandos, thereby provoking a policy revision a few weeks later – the first relaxing of the blockade, and in the worldview of Hezbollah and Hamas, an achievement for Islamists on an issue on which secular Palestinians had failed to force any change.

“Israel Preparing for Flotillas Like on Eve of War” screamed a June 23 headline on Al-Manar. (Hezbollah also threatened this week to sue the United States for libel, claiming that Washington and its Arab allies had spent $500 million “to bribe people to criticize Hezbollah.”)

Challenging the Gaza blockade is a popular unifying cause in Lebanon, appealing to nearly every constituency, even those who oppose Hezbollah. Defending Palestinian rights in Gaza also provides a welcome distraction for Lebanese politicians currently struggling with the matter of the second-class status of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

For Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s supreme leader and a gifted orator, the affairs of the boats and the siege have created a ripe opportunity to make rhetorical hay, and – once again – to position Hezbollah as the beneficiary of an effort to which it contributed nothing tangible. (Not unlike Hamas, the main, and perhaps unintended, beneficiary of the last flotilla.)

From Nasrallah’s most recent speech (translation by Al-Manar):

This is a lesson for some of those who preach the policy of humiliation, delusion and wishful thinking that only result in disgrace. On the other hand a policy based on power can accomplish a lot. …

There is a good chance today to end the blockade imposed on Gaza and this requires more Freedom flotillas. … We have to benefit from the Freedom flotilla to remind the world of Israel’s massacres

Israel’s New Crisis at Sea

Writing at The Daily Beast, I look at what the future holds for Israel’s Gaza policy now that the Netanyahu government has decided to relax its blockade. I suspect even more challenges to the current legal arrangement which puts both Israel and Gaza in limbo. Read the whole piece here.

If the Netanyahu government translates Sunday’s statement into a substantially more open border with Gaza, they’ll find the calls for a new approach to Gaza just as shrill as ever—perhaps even more shrill now that Israel has backed down on one element of the blockade. What Gazans object to is that Israel claims to have ended any vestiges of occupation of Gaza when it pulled out the Jewish settlements in 2005—and yet, at the same time Israel retains control of Gaza’s sea and land borders.

That’s the nub of the problem, and not the shortage of foodstuffs and medicines. If Israel resolved Gaza’s humanitarian concerns, the Palestinians in Gaza would still be incensed that they can’t travel, import or export goods without Israel’s permission.

In other words, it’s not the cilantro; it’s the siege that’s the problem

A Viable Palestinian State?

A small group of technocrats has doggedly kept at the hard work of designing a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, long after the Oslo Process itself collapsed. Two of its longest serving advocates – Saeb Bamya, the Palestinian economist, and Ron Pundak, the Israeli director of the Peres Center for Peace – tried to answer the lofty (and perhaps rhetorical) question put forth by their host from The Century Foundation: After the Gaza blockade, can Palestine’s economy be viable?

A small group of technocrats has doggedly kept at the hard work of designing a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, long after the Oslo Process itself collapsed. Two of its longest serving advocates – Saeb Bamya, the Palestinian economist, and Ron Pundak, the Israeli director of the Peres Center for Peace – tried to answer the lofty (and perhaps rhetorical) question put forth by their host from The Century Foundation: After the Gaza blockade, can Palestine’s economy be viable?

The two men made a concerted and heartfelt pitch for a return to the ethos of building two states side by side. According to Bamya, more than anything else Palestinians need a “normal business environment,” which requires Israel and the Palestinian Authority to implement the 2005 agreement on access and movement that would free the flow of people and goods between the West Bank, Israel and Gaza. He and Pundak insisted that only a two-state solution could accommodate both Jews and Palestinians.

Daniel Levy, a fellow at the New America Foundation who was a member of Israeli negotiating teams in the latter stages of Oslo and at the 2001 Taba conference, tried without success to pin the two-staters down to specifics: How exactly would they like to Israel and the United States to relate, economically, to Gaza and the West Bank?

I asked Bamya and Pundak at what point they would determine that a self-sustaining Palestinian state was no longer viable. Their answer, it appeared, was that there was no such point. “Everything is reversible if there is political will,” Bamya said. Pundak added, “We are basing everything on the solution of two states.”

The final questioner, retired Pakistani diplomat Ahmad Kamal, said he hated to appear impolite to the panelists, but said he thought all their assumptions were specious. In the long run, Kamal said, a Palestinian state “dissected” between two unconnected geographical regions, Gaza and the West Bank, would never be sustainable; nor, he said, was an Israel that had hostile relations with its neighbors and which depended on the backing of the United States. “What about the possibility of a one-state solution?” Kamal asked.

“One state won’t happen,” Pundak said emphatically. “We hate each other too much. We will kill each other.”

“I won’t kill you,” Bamya said, provoking some laughter.

“Our grandchildren who don’t exist yet would kill each other,” Pundak earnestly replied.

“Inshallah,” said Daniel Levy, bringing down the house.

Tariq Ramadan in the New World: The Atrophied Debate About Islam

Six years after the U.S. government banned him from the country, the celebrity Islamic scholar Tariq Ramadan landed in New York last week. The American government’s decision to reverse the ban marked a great victory for free speech advocates. Sadly, though, the conversation on stage suggested that a decade since the launch of the “Global War on Terror” (and despite the panelists’ best efforts) our public discourse is still distorted by the kind of thinking that begins with the question “Why do they hate us?” and unfolds with the false sense that the world’s billion-plus Muslims function as a monolithic and fanatical bloc.

Ramadan’s first public appearance, at Cooper Union in downtown Manhattan, had the kind of pomp and fanfare rarely associated with an intellectual event. People lined up around the block and paid $15, more than the price of a movie, to hear Ramadan and four other intellectuals brush every hot-button issue concerning the intersection of Islam and the West. Can Muslims loyally embrace Western secular governments? (Ramadan says of course.) Does Islam have a fundamental problem with women? (Historian Joan Wallach Scott says Westerners who care little for women’s equality in their own societies project their feminist discourse onto the Islamic world.)

Underlying the entire discussion was the general suspicion among some intellectuals on both the right and the left that Islam is fundamentally illiberal, and therefore incompatible with values like secular government, religious pluralism, and free speech. Tariq Ramadan – in part by choice, in part by happenstance – has been cast in the role of spokesman for “moderate Islamism.” He’s an Oxford professor; he’s religious; he’s the grandson of the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood; he’s a Swiss citizen of Egyptian origin; he’s a prolific writer; and he vigorously engages in the public sphere. At one time or another he’s confronted most questions about Muslims and their role in the West, and he’s left behind an ample public record to pick through. As a result, he’s become a favorite sounding board/punching bag/totem for people who argue about Islam and the West.

It’s only the beginning of his dialogue with the American public, and this first appearance was meant as much to celebrate the lawsuit that lifted Ramadan’s visa ban as it was to debut a serious discussion about Islamism in America and Europe. Despite the panel’s title – “Secularism, Islam and the West” (you can listen to the full audio here) – some questions seemed stuck in America’s first encounter with Islam after Sept. 11: Do you think it’s wrong to stone women? Does Islam countenance homosexuals? (Ramadan answered in the affirmative.)

The problem with such questions is that they presume first that Ramadan speaks as a religious authority, which he does not, and second that contemporary American political debates apply to the Islamic world, and should be used to frame some inquest into whether “Muslims,” as if they are a single entity, are good or bad. This “What went wrong?” ethos presumes that the fundamental matters of concern in the Islamic world, and among Muslim communities of the West, include gay rights, and whether women can drive or should be subjected to Taliban-style religious law. In fact, in the vast un-free zones of the Islamic world, people chafe at much more basic problems: the absence of any political rights, the lack of basic governance, stifled development, and in many places, widespread violence. Similarly, in the West, despite the outsized attention paid to extremists, the vast majority of Muslims agitate neither for religious rule nor for the cultural fundamentalism of the fanatics in Al Qaeda, the Taliban and the Shabab. When we want to engage the problem of violence and religious fanaticism meaningfully, we ought to do so with specificity. Do not ask “Why do they hate us?” Ask “What draws certain middle class youth away from politics and into the nihilistic violence of Al Qaeda?” or “Why do certain religious thinkers rule it’s okay to target civilians in a time of war?”

A more interesting debate began, when George Packer, a writer for The New Yorker, politely but with determination confronted Ramadan about his grandfather. What did Ramadan have to say, Packer asked, about his grandfather’s embrace of a Palestinian leader who had collaborated with the Nazis? Packer invited Ramadan to condemn the World War II-era mufti of Jerusalem for his Nazi sympathies, and also to go a step further and condemn his own grandfather, Hassan al-Banna, for embracing the mufti and ignoring the mufti’s work on behalf of the Nazis.

This question might seem obscure, but it raises a lot of the baggage with which the West often saddles Islamists and Palestinian activists – and which many of those same activists in turn have failed to confront and discard. Many Western liberals (and many Israelis, and many secular Muslims) believe that a profound stream of anti-Semitism and authoritarianism courses though Islamism. Those Islamists who engage in the debate reply that they oppose Israeli policy and not Jews, and that they would not govern in the dictatorial manner of Islamic movements like the Taliban or Al Qaeda. Supporters of a Palestinian state feel unfairly bludgeoned, held to a standard of historical perfection spared supporters of Israel: Why, they ask, do they have to account for their forebears’ behavior in the 1930s and 1940s while the world gives Israel a pass on the record of the Irgun and the Stern Gang? That question merits another essay, but in short, there’s plenty of public discussion about Israel’s (and the West’s) legacy of violence, and morality is not a zero-sum game. You don’t have to wait for your political rival to acknowledge right and wrong and confront a troubled past before asking yourself tough questions.

The problem comes in cases like that of the mufti of Jerusalem, or the waffling of Hassan al-Banna. Why don’t Islamist activists go out of their way to condemn their predecessors’ mistakes, or the excesses (or racism) of some of their peers? It’s fair enough that Ramadan wants to put the mufti’s actions in their historical context, just as many Palestinians and other Middle Easterners want to contextualize the acts of various militants in the ongoing war between Palestinians and Israel. But the quest for context need not prevent those advocates from decrying actions that are clearly wrong or misguided. The Palestinian case, presumably, does not rest on the infallibility of its leaders and its gunmen. Nor should proponents of a Palestinian state fear they would jeopardize their case if they were to condemn support for the Nazis, or for that matter, the targeting and killing of civilians. There are plenty of Palestinian, Islamist, and, for that matter, Israeli, constituencies that roundly condemn historical errors and criminal conduct by their fellow partisans; in the case of activist Islamism, however, such arguments are rarely heard from the leadership.

In Ramadan’s case, he’s neither a political leader nor religious jurist. The claims of his most vociferous critics notwithstanding, he’s neither two-faced nor an apologist for extremism. (Ian Buruma’s New York Times Magazine profile explores Ramadan’s reputation as slippery; Laura Secor in suscriber-only The Boston Globe archive chronicles Ramadan delivering the same message to Muslim and non-Muslim audiences.) However, as an articulate thinker who has assumed the burden of convincing Western Muslims that there is no conflict between their religious identity and their role as citizens of secular Western democracies – and as an interpreter between Islamism and the secular West – he is in a unique role to confront this quandary. He wants to be a bridge, and he seems to have the temperament and intellect to tackle that role.

Many Western critics, however, still aren’t interrogating Islamic thinkers and leaders with any granularity or nuance, talking as if all religious Muslims thought part and parcel with fundamentalist Wahabbis. A tract distributed at the event by one Lorna Salzman entitled “The Muslim Suppression of Free Speech: An Abridged History” comes from that blinkered tradition. Ramadan himself is a victim of “Muslim suppression of free speech,” if properly understood; in addition to being banned from the United States for so many years, he is still prohibited from speaking in six majority-Muslim countries. Their authoritarian rulers clearly consider the Oxford professor a greater threat than the West does. For his part, Ramadan should take head on this well of doubt about the Islamic world’s contemporary history and problem with violent extremists, and craft an unapologetic response that doesn’t fear apologizing when appropriate. Dialogue and a more nuanced view of Islam by the skeptical quarters of the West won’t begin until both parties have taken a step closer to the riverbanks from which they contemplate one another.