How Religion Lost the War

My latest column in The Boston Globe.

Fundamentalism’s rise just shows that the secular state has won, says political scientist Olivier Roy

If you read the news, it can feel impossible to escape the growing influence of religious fundamentalism. Christian evangelicals set the talking points of the Republican primaries, and America’s leaders speak about God with an insistence that might have made the authors of the Constitution blush. Religious parties have become steady players in the politics of secular Europe. Meanwhile, Islamists from Morocco to Malaysia campaign to eliminate all barriers between the mosque and the state. With religion so ubiquitous in politics, it sometimes appears that the world may be crossing the threshold from the age of secularism into one of religious states.

But what if all this religious activism and faith-based politics herald not a new dominance but a passing into irrelevance? That’s the counterintuitive assertion of Olivier Roy, a French political scientist and influential authority on Islam, who has now turned his eye on the growth of fundamentalism across all religions.

As Roy argued in the book “Holy Ignorance,” published late last year, old-line religions with organized power structures are in a global decline, overtaken by fundamentalist sects such as Islamic Salafis and Christian Pentecostals, which make a charismatic appeal to the individual. But in fact, Roy argues, this trend suggests that religion has effectively given up the struggle for power in the public square. Despite the extremist rhetoric of televangelists in the American Midwest or the Persian Gulf, these growing religions are really just a reaction to the triumph of secularism. They demand a total personal commitment from their adherents: abstinence, sobriety, frequent prayer. But, though their leaders may talk of making America an officially Christian nation or of establishing pure Islamic states in places like Egypt, they carry none of the real institutional or military weight of established religions in history.

“The religious movements are here, they have an agenda,” Roy says. “I never deny that. I say that political ideologies based on religion don’t work. You can’t manage a country in the name of a religion.” In other words, as he interprets it, the world is not in the grip of a clash of civilizations; religious movements are just growing more strident because they are detached from the culture of nations. An age of vocal religious fundamentalists, contrary to our expectations, may also be an age of safely secular states.

If Roy’s hypothesis proves correct, it stands to change international politics by making us much less concerned about religious extremism. It could give secular forces new power to deal with fundamentalist organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood; since their religious agendas are not likely to dominate any nation’s political life, they could be dealt with on a purely material level. At home, American policy makers could rest assured that extreme fundamentalist positions on gay rights or teaching evolution in schools would inevitably be leavened by the political realities of a pluralistic, secular society. For those who treasure secular governance and separation of church and state, Roy’s hypothesis–if the 21st century bears it out–would mean there is far less in the world to fear.

In “Holy Ignorance,” Roy presents what reads like an alternate history of the last half century, narrating some familiar facts but drawing counterintuitive conclusions. Fundamentalist religion has been on the rise worldwide since the 1950s. In the Islamic world the fastest growing sect is the Salafis, who advocate a return to 7th-century piety. Among Christians, evangelical Christian sects like Mormons, Pentecostals, and Jehovah’s Witnesses are the fastest growing, while ultra-Orthodox Jews are gaining within the Jewish community. Almost nowhere, with the exception of Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, has the fundamentalist revival taken the form of a single religious group, unified behind one leader, trying to take over a country. Instead, ascendant fundamentalists are a fractious group. Moreover, their growth comes at a time when pluralistic, secular politics predominate, and religious institutions have less power than ever before. In a borderless, globalized world, the only religions that grow are exactly those that sever themselves from a specific national or cultural context, and appeal to universal humanity. Such religions might sound louder or more shrill, but they’re also by definition less significant to the political and cultural life of nations.

Roy’s argument has grown out of decades studying the interaction between religion, politics and culture. As a young man, Roy writes, he was jarred by the arrival of a born-again Christian in his religious youth group. It was his first encounter with charismatic religion. After he established himself as an authority on the Islamic world, Roy began to argue by the 1990s that Islamic fundamentalists would not manage to win over their own societies, despite their violent heyday; his 1994 book, “The Failure of Political Islam,” was criticized by some as premature, but now most scholars agree with its conclusions.

From today’s vantage point, religious politicians and commentators seem like a force to be reckoned with, but it’s instructive to compare them to the mainline religious institutions that used to wield power. During the Middle Ages, institutional religions possessed tremendous real-world power. The Catholic Church decided which leaders had legitimacy and triggered massive wars. With the Industrial Revolution, Christian missionary activity inextricably intertwined with European colonization. Even as recently as 1960, the Vatican held such sway that American voters feared John F. Kennedy would take orders from the pope; his edicts set the parameters of European social policy well into the 20th century. Meanwhile, in the Islamic world, until colonialism eroded the authority of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, the supposedly all-powerful caliphs and their governors could be overthrown when religious scholars withdrew their support.

Gradually, however, secularism took root. After the French Revolution, the number of European leaders claiming a divine right to rule dwindled. Even the caliphate in Istanbul began to look like a secular empire with vestigial religious trappings. Modern nation states were more concerned with holding territory and controlling populations than with matters of faith. Roy argues that even when they invoked religion to gain legitimacy, modern states were engaged in an inherently political quest, in which religion was marginalized.

It was the loss of direct religious power that prompted the rise of what Roy calls “pure” religions: sects that appeal to the universal individual. Old-line religions talked explicitly about power and considered themselves more powerful than states. As they declined, Roy says, the public began to move to groups that were more charismatic and focused on faith in the private sphere–Mormons, Pentecostals, Tablighis, Salafis, ultra-Orthodox Jews. We call these sects “fundamentalist” because they claim to return to the founding texts of their faith, stripping out the practices that had accreted in the centuries since the founding of their respective religions.

This return to basics has visceral appeal to those seeking a faith. But millions of born-again evangelicals, seeking salvation from a mosaic of political backgrounds, are unlikely to develop the clout the Vatican once had. Look closely at the surge of Salafists around the Islamic world, and you’ll find extreme fragmentation, with rivalries between the followers of competing sheikhs often taking priority over concern with unbelievers. The religions that are actually growing and winning converts are resolutely not political monoliths in the making.

In Roy’s view, the pure new religions employ simplistic ideas that sound universal and appeal to new converts, but whose vigor can be hard to sustain generation to generation. These charismatic, fundamentalist religions depend on constant renewals of faith, Roy says, and depend on the zeal of new converts for their growth and dynamism. Fundamentalist sects can afford to take extreme positions on belief, Roy says, precisely because they have none of the constraints of governance and authority.

Not everyone is convinced by Roy’s interpretation. Even if there are hardly any real theocracies left in the world, religious hard-liners still influence political life directly in countless places. One need look no further than the role of born-again Christian activists in the Republican Party, or the growing enrollment of Salafist political parties in Egypt.

Karen Barkey, a Columbia University sociologist, argues that Roy has overlooked the resilience of fundamentalism. Yes, secular culture has largely taken the reins of power, but it’s a two-way process; religion has fought back, and tailors its message and approach to local constraints. Roy is too optimistic when he claims that fundamentalism always wears itself out, Barkey says. Religion is asserting itself within evolving cultures, including democratic ones, and will continue to have great influence. “Some forms of religious fundamentalism may well be disappearing into the ether of abstraction,” Barkey wrote in a barbed essay contesting Roy’s view in Foreign Affairs, “but in most cases, religion, culture, and politics are still meeting on the ground.”

For those watching that clash, too, it can be hard to credit Roy’s interpretation. In phenomena like the rise of the evangelical right in American politics and Islamic fundamentalists in the Arab world, Roy sees a sign of defeated religion that has been pushed from the political playing field. But others argue that religion crucially shapes politics in ways that scholars, most of whom are secular, don’t well understand. Grandees of political science recently convened an initiative to systematically increase their field’s study of religion, and published a volume through Columbia University Press this year called “Religion and International Relations Theory.”

Still many scholars agree with Roy that the importance of religious extremists has been overstated. Alan Wolfe, director of the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life at Boston College, says that Roy provides a convincing riposte to those like Jerry Falwell, who called for religion to directly shape legislation. Wolfe believes Roy’s assertion that religious influence on politics will continue to wane.

The implications of Roy’s theory are stark. If he is correct, American policy makers can step away from the entire framework of “the clash of civilizations” and “the rise of Islam,” and finally begin to deal with political actors at face value. Iran’s ayatollahs, for example, are better understood as extreme nationalists rather than religious fanatics, Roy has written. While religion matters to Hindu nationalists in India, Shas Party members in Israel, and followers of Hezbollah in Lebanon, it’s their specific nationalist aims that have made them politically powerful players. In political terms, their faith is essentially irrelevant.

Most of all, Roy’s theory offers the possibility of no longer seeing our conflicts as religious wars. In 2003, Lieutenant General William Boykin scandalized secular Americans when he described battling a Muslim fighter and said, “I knew that my God was bigger than his. I knew that my God was a real God, and his was an idol.” If Roy is correct, such rhetoric is simply beside the point; as our century wears on, extreme religious belief will more and more be just a fringe phenomenon, unworthy of the attention of governments.

The Ramadan Moon, Lost in Haze

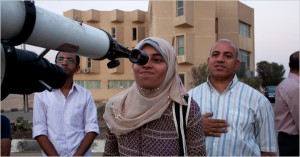

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

“It looks like trouble,” he said.

His deputy, Ahmed Fathy, concurred with a sigh, “I’m afraid we’re not going to see anything tonight.”

The two Egyptian physicists on Tuesday night had a delicate mission: They were charged with providing the scientific imprimatur to the start of the holiest time for Muslims worldwide, the lunar month of Ramadan. Egypt plays a major role in this ritual because it is the seat of Al Azhar, the world’s most prominent Sunni Muslim institution.

According to the Koran, Ramadan, a month of fasting and prayer, begins on the first night that the crescent moon is visible to the naked eye. For centuries, clerics and laymen jostled to spot the Ramadan moon first and often differed. An area with cloudy skies or a different longitude and latitude might declare Ramadan a day or even two later than the rest of the Islamic world.

Modern astronomy long ago took the mystery out of the lunar calendar, whose year lasts some 11 to 12 days less than the Gregorian year used by most non-Islamic countries.

Mr. Mahmoud, the president of Egypt’s National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, publishes a hefty book of tables that lists the precise time and location that the Ramadan moon will appear in various cities throughout the Islamic world.

But science, it seems, can go only so far.

“We know it’s there, but Shariah requires us to see it with our eyes,” Mr. Mahmoud explained. The grand mufti, Egypt’s highest religious authority, awaits a report from Mr. Mahmoud’s team and from a secondary group of spotters organized by the Egyptian National Survey Authority.

Ayatollah Fadlallah’s Legacy

Lebanon’s Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah died on Sunday, snuffing out one of the most important voices for reform and restraint inside the milieu of Shia Islamism. As I wrote in Fadlallah’s obituary in The New York Times, the cleric had made his name as an advocate for the Shia awakening in the 1960s and 1970s, and then as a justifier of suicide bombings by Islamists.

Lebanon’s Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah died on Sunday, snuffing out one of the most important voices for reform and restraint inside the milieu of Shia Islamism. As I wrote in Fadlallah’s obituary in The New York Times, the cleric had made his name as an advocate for the Shia awakening in the 1960s and 1970s, and then as a justifier of suicide bombings by Islamists.

But he also won droves of supporters all across the Islamic world, including the non-Arab nations, because of his work on family law. He found that women should have an easier time winning divorces under Islamic law, and that they have the right to defend themselves from domestic violence. He directed vast sums of money to hospitals and charity groups, even setting up for-profit businesses like hotels and gas stations in under-served Shia areas and then funneling the proceeds to his social services network. Most of the Shia women I know, even those who sympathize with Hezbollah, considered Fadlallah their religious reference.

In January 2009, I interviewed him at his official headquarters around the corner from the mosque where he preached. He railed against the infighting in the Islamic world between Shia and Sunni Muslims, and between Muslims and Christians. Eventually, he said, America and Iran would arrive at a rapprochement, and so too would Israel and its neighbors (this last statement surprised me the most).

To a Westerner, it might be hard to distinguish among the different marjas, or “sources of emulation,” that devout Shia Muslims follow. They all believe that religious jurists have the right to issue fatwas on everything from marital relations to geopolitics. Beyond this common point, however, leaders like Fadlallah – and to a lesser extent, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani in Najaf – have provided a very different model than some of their counterparts in Qom, who advocate the Iranian model of wilayat al faqih, or direct rule by the jurisprudent (that is, the ayatollahs govern directly.)

Fadlallah believed the authority of the clerics depended on their authority among the people (and not solely from their divine link to God). He also believed that Islamic resistance had to retain its “humanism,” and therefore he condemned acts and movements that considered terrorist – like the Sept. 11 attacks, and the ongoing efforts of Al Qaeda. “We are not at war with the American nation,” he told me.

There aren’t many religious leaders whose views carry such weight and yet are willing to criticize their own followers and the movements that they inspire. Now there’s one fewer.

Islam’s Beginnings

The first followers of Christ didn’t consider themselves ’’Christians’’; they were Jews who believed that a fellow Jew named Jesus Christ was the long-awaited messiah. It took centuries for Christianity to evolve and solidify as a distinct faith with its own doctrine and institutions.

The first followers of Christ didn’t consider themselves ’’Christians’’; they were Jews who believed that a fellow Jew named Jesus Christ was the long-awaited messiah. It took centuries for Christianity to evolve and solidify as a distinct faith with its own doctrine and institutions.

In ’’Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam,’’ University of Chicago historian Fred M. Donner wants to provide a similar back story for Islam — a religion which, in the popular imagination, sprang wholly formed from the seventh-century sands of Arabia. Mohammed preached at the juncture of the Roman and Sassanian empires, winning support from Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and various deist polytheists. According to Donner, Mohammed built a movement of devout spiritualists from many faiths who shared a few core beliefs: God was one, the end of the world was near, and the truly religious had to live exemplary lives rather than merely pay lip service to God’s laws. It was only a century after Mohammed founded his ’’community of believers” and launched the great Islamic conquest that his followers started to define their beliefs as a distinct religious faith.

Devout Muslims — who model their lives directly on the mores of the Prophet and his companions — will be surprised to read that Mohammed welcomed Christians and Jews into his monotheistic movement. In fact, Donner suggests, the entire narrative of Islamic conquest misinterprets the ecumenical nature of the early believers. Mohammed, it appears, didn’t require his followers to renounce their religion; early Islam, in this read, was more a revival of existing faiths than a conversion.