We are the war on terror, and the war on terror is us

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

THE FIRST signs of America’s transformation after 9/11 were obvious: mass deportations, foreign invasions, legalizing torture, indefinite detention, and the suspension of the laws of war for terror suspects. Some of the grosser violations of democratic norms we only learned about later, like the web of government surveillance. Optimists offered comforting analogies to past periods of threat and overreaction, in which after a few years and mistakes, balance was restored.

But more than 15 years later — nearly a generation — we have not changed back. Shocking policies abroad, like torture at Abu Ghraib and extrajudicial detention at Guantanamo Bay, today are reflected in policies at home, like for-profit prisons, roundups of immigrant children, and SWAT teams that rove through communities with Humvees and body armor. The global war on terror created an obsession with threats and fear — an obsession that has become so routine and institutionalized that it is the new normal.

The perpetual war footing has led to a militarization of policy problems under the Trump administration. The share of recently active-duty military officers in senior policy positions exceeds the era after World War II, historians say. Border police chase people down outside homeless shelters and clinics, deport legitimate visitors, and swagger around airplane jetways demanding identification. And another burst of defense spending is just around the corner.

All of this is a sign that the United States has fallen into a trap familiar to many former colonial powers: They brought home their foreign wars at great cost to their democracies. Colonial Great Britain normalized inhumane treatment of civilians abroad in service of empire, and then meted out the same Dickensian abuse to the poor at home. In its futile effort to hold onto its colony in Algeria, France rallied anti-Islamic sentiment and pioneered indiscriminate counterinsurgency; as a result, to this day in France, religious freedom and suspects’ legal rights still suffer. Liberals in Israel argue that the practices necessary to perpetuate the occupation of Palestinian territory have fatally eroded the rule of law.

Indeed, the longer a conflict endures, the more deeply all parties to it are corrupted; citizens asked to misbehave on behalf of their country find they can’t stop when they return home or go off duty.

For more than a decade and a half, America has embraced a vast military campaign that relied on major shifts in US values and policies. A covert assassination program targets terror suspects with no judicial process. Many bedrock civil liberties have been traded away. Some initial excesses, like the use of torture, were curbed. But the norm is still inhumane forms of detention, and abuse that meets the definition of torture. Meanwhile, the United States has maintained what is for all intents and purposes an extrajudicial gulag in Guantanamo Bay since 2001.

Collectively, all these data points have struck with the force of a meteor against America’s culture of due process and institutional checks and balances.

As this new mindset took root, even some of its architects took notice — and were alarmed. Midway through Obama’s presidency, a White House adviser confided concerns about the executive branch’s “kill list” and accelerating use of drone strikes. “One day historians are going to excoriate us for the kill list, and they’re going to ask why no one questioned what we’re doing,” this adviser said.

We’re still waiting for that day. In the meantime, we must understand the full extent of the damage. America became its war on terror, abandoned its principles to visit horrific violence abroad, and then brought into domestic politics an ease with lawlessness, caprice, imperial-style occupation. A global war, by definition, must also be waged at home.

A sizable contingent today believes that the military solution is the only and best one for many problems, from terrorism to corruption to managing diplomatic relations. And while knee-jerk militarism is poisonous for a republic, we would do well to remember the failures of civilian politics that make even generals of dubious repute like David Petraeus seem like potential saviors.

“We’re pell-mell down a road that we don’t even we realize we’re on anymore because we’ve got so used to the military option,” said Gordon Adams, a professor emeritus at American University and co-editor of the book “Mission Creep: The Militarization of US Foreign Policy?”

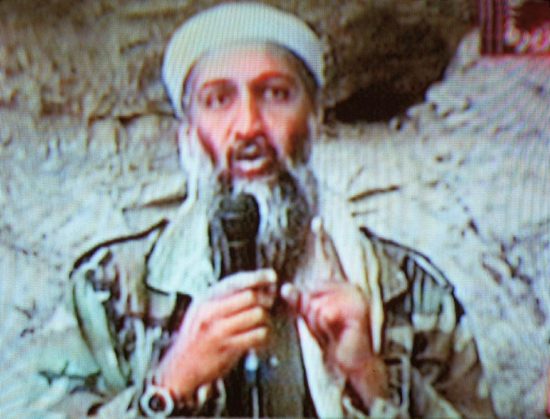

It’s not that military officers are bad or necessarily wrong — it’s that they offer just one perspective on policy problems, and they’ve been trained to consider one tool: force. That’s well and good when military officers are in a room with other experts with other perspectives, debating how best to deal with Osama bin Laden. It makes less sense when military officers, active-duty and retired, are the only people in the room debating US policy toward Russia, China, the Middle East, or issues even further from their lane, like airport security and international trade. It becomes absurd when doctrines that failed so spectacularly in Iraq and Afghanistan somehow worm their way into local police departments in the United States.

Immediately after the attacks of 9/11, America’s political class decided its only goal was stopping future terror strikes. Legislators forsook legislative oversight. Courts were reluctant to limit metastasizing executive power. Rights were stripped by laws like the USA Patriot Act, which watered down protections against overzealous law enforcement hard won over a century. It’s not hard today to draw a line from the bullying jingoism of 2001, when opposing the Patriot Act reeked of disloyalty or treason, to the election of President Trump, and his reckless “America First” positions that jeopardize global security in 2017.

A bipartisan consensus views remote strikes against suspected terrorists as an efficient refinement on the early, labor-intensive, versions of counterterrorism. Although the rest of the world still musters outrage when civilians are killed, the issue has all but vanished domestically. There is simply no domestic political cost for accidentally bombing a hospital in Afghanistan, or killing 10 children in Yemen, or the deaths of dozens of civilians in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere. Think about the shock that the My Lai massacre caused to American politics less than half a century ago. Now consider the cultural shift whereby the public accepts and ignores routine massacres — usually committed with air power, and sometimes with a plausible claim that accidents were honest mistakes or not directly America’s fault or the victims were sympathetic to American enemies, if not actually guilty of anything.

This is a sea change. In the 1970s, when the Church Commission revealed that the CIA, sometimes with presidential support, had assassinated foreign leaders, it was a scandal. The uproar curbed the powers of the CIA for decades.

Compare that to the last 16 years; black ops are fetishized and widely supported. There are no checks and balances. The president can — and has — decided to assassinate terror suspects, including American citizens. Hardly anyone raises a peep except for the ACLU and a handful of other minor constituencies with a hard-line commitment to civil liberties. That’s how strange, and troubled, is our adoption of a heedless counterterror gospel. Obama seemed to order assassinations with such care and deliberation that criticism only came from the fringe; Trump critics will find it difficult now to object to a kill list on grounds not of principle but of personnel.

Afghan war veteran Brendan O’Byrne articulated this disturbing transformation in an essay this month in the Cape Cod Times. He likened the endless quest to kill terrorists to cycles of violent abuse inside families. As a troubled youth, he recalled, he attacked his father, who then shot O’Byrne in self-defense. “America is like my father, creating the very thing it has to kill before it kills them,” O’Byrne writes. “Where is our responsibility for creating the terrorists we are now fighting?”

America has confused self-defense with an impulse to kill “every possible threat,” O’Byrne continues: “We run the risk of becoming the very thing we claim to be fighting against — terrorism.”

Our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have stretched on so long they’ve become the fixed backdrop to a country at war against terror in more places than the average American can track. The Pentagon now operates in roughly 100 countries worldwide. To be American is to be at war.

“I’m teaching college students this semester — they can barely remember a time when these wars were not underway,” said Jon Finer, a former war correspondent in Iraq who later became chief of staff to then-secretary of state John Kerry. “Combat has become a normal, regular feature of American life.” Over a decade Finer switched careers, from journalist to senior national security official, only to find the American military still engaged in counterinsurgency with jihadis in the same provincial deserts of northern Iraq.

The war against terrorism aspired to reduce to zero the number of attacks on American territory — no matter how many attacks that would require America to conduct, and provoke, abroad.

A society that embraces war without end eventually stops recognizing that its initial adrenaline response is abnormal. Fear becomes the baseline. The mirage of zero-risk and the cult of war we embraced to find it have systematically warped our politics and society.

The extremes that led to Trump’s election — xenophobia, race-baiting, fear, disregard for rights — were nurtured by the many Americans mobilized to execute US foreign policy in the post-9/11 war zones. Military personnel, diplomats, aid workers, ideologues, apolitical contractors: Hundreds of thousands of Americans were steeped in war and brought that culture home. If you’ve learned one, brutal way to search cars at a checkpoint in Iraq, it’s hard to shift to the gentler methods when you’re working a few years later as an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent or police officer in middle America.

Trump’s America is our America, and it’s been taking shape for many long years. We won’t restore the balance and get the best of America back until we decide to end our war on terror and focus anew on the American rights that undergird our security even more than prisons and SWAT teams.

Interesting . . . isn’t it amazing that it was the liberal Democrat Woodrow Wilson entering the US in WWI, the liberal Democrat Roosevelt pushing for US entry into WWII, the liberal Democrat Truman responding to Korea, the liberal Democrat Johnson giving us guns, not butter. the liberal Democrat Obama dithering with Syria. The shock of My Lai was to me, an infantry combat veteran of Vietnam, that only a lowly lieutenant was convicted of a crime when higher ranks had to be aware of every contact with “enemy.” On air assaults to cordon a suspected enemy village I can tell you I was not thinking about judicial process. It’s nice, comforting, but willfully naïve to think if US ends its war on terrorism, terrorism will no longer impact the US.

The War of Terror did not begin after 9/11. It was America’s War of Terror that GHW Bush launched (once he and Reagan had ensured The Soviet Union could no longer hamper our mischief abroad) against Iraq that showed the US for what it was,a self-righteous bully that for the sake of US corporations risks US assets and taxpayer-provided military to enable its “People”, in the form of corporations, to commit any international crime they can profit from, such as Halliburton’s use of horizontal drilling to revitalize the falling output of Kuwait’s Burgan oil fields, with oil siphoned from underground cross-border incursions in to Iraq’s fields. For hiding and abetting this crime the US public is still paying today, yet few know that then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney knew exactly what was going on and gave Halliburton cover, for which, as VP, he was still receiving checks when those planes slammed into the Twin towers.