What Aleppo Is

Boys make their way through the rubble of damaged buildings in the rebel held area of al-Kalaseh neighborhood of Aleppo, Syria, September 29, 2016. Reuters/Abdalrhman Ismail

[Published in The Atlantic.]

BEIRUT—For at least a year before the summer of 2016, civilians and fighters in rebel-held East Aleppo prepared for a siege they believed was both avoidable and inevitable. Correctly, it turns out, they calculated that the opposition’s bankrollers and arms suppliers—the United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other “friends of Syria”—cared little for the well-being of civilians in rebel-held areas. Through the spring, contacts inside Aleppo prepared for the siege, expending minimal effort on appeals to the international community, which they assumed would be futile.

For all the world-weary resignation of the opposition fighters and other residents of rebel Aleppo, they have a well-earned pride in what they’ve done. They’ve maintained their hold on half of the jewel of Syria, and under withering assault, have cobbled together an alternative to Bashar al-Assad’s rule. “From the beginning of the revolution, we held Aleppo as the role model of the liberated city, that holds free elections, has an elected city council, and elected local committees that truly represent the people,” Osama Taljo, a member of the rebel city council in East Aleppo, explained over the phone after the siege began in earnest. “We insisted to make out of Aleppo an exemplar of the free Syria that we aspire to.”

Unfortunately, Aleppo has become an exemplar of something else: Western indifference to human suffering and, perhaps more surprisingly, fecklessness in the face of a swelling strategic threat that transcends one catastrophic war.

The last few weeks have piled humiliation upon misfortune for Aleppo, one of the world’s great cities, and already a longtime hostage of Syria’s never-ending conflict. Aided by the Russian military and foreign sectarian mercenaries, Syrian forces encircled East Aleppo over the summer. Rebels briefly broke the siege, but Assad’s forces fully isolated them just as Russia and the United States put the finishing touches on a dead-on-arrival ceasefire agreement that, contrary to its stated purpose, ushered in one of the war’s most violent phases yet. Instead of a cessation of hostilities, Syria witnessed an acceleration of the war against civilians, with East Aleppo as the showcase of the worst war-criminal tactics Assad has refined through more than five years of war.

Sieges violate international law, as well as specific United Nations resolutions, that, on paper, guarantee access to humanitarian aid to all Syrians but which in practice the government has disregarded. Aleppo—the biggest prize yet for Assad—has also been subjected to his most destructive assault. Throughout East Aleppo, Syrian or Russian aircraft have ruthlessly bombed civilians, singling out all healthcare facilities and first-responder bases. Bombs have ravaged well-known hospitals supported by international aid groups, along with the facilities of the White Helmets, the civil defense volunteers famous for digging casualties from rubble.

As if to test the proposition that the international community has just as little concern for its own reputation as it does for the lives of Syrian civilians—nearly half of whom have been displaced from their homes nationwide—Russia apparently chose, on September 19, the seventh day of the ceasefire, to bomb the first aid convoy en route to rebel-held Aleppo. That decision will be remembered as a fateful one.

Russia and Syria were following a timeworn blueprint: Use force to kill and starve civilians, then lie brazenly to avoid responsibility. In this case, the evidence is too clear and the trespass too toxic to let pass. So far, we’ve seen a sharp turn in rhetoric from the UN and Washington. Sooner or later, whether in the twilight of the Obama administration or in the dawn of his successor’s, we will see a much harder “reset” in Western relations with Russia.

For years, voices from Syria have raised the alarm. After years of dithering, even some members of the international community had the decency to follow suit, like Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. “The country is already a gigantic, devastated graveyard,” al Hussein said this summer, warning Syria’s belligerents that sieges and intentional starvation campaigns amount to war crimes. “Even if they have become so brutalized [that] they do not care about the innocent women, children, and men whose lives are in their hands, they should bear in mind that one day there will be a reckoning for all these crimes.”

Belatedly, Western leaders are joining the chorus. UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon, who avoided taking a stand during years of violence against humanitarian organizations by the Assad regime, now publicly accuses Syria and Russia of war crimes. On September 30, the one-year anniversary of Russia’s direct entry into the war, Gareth Bayley, Britain’s Special Representative to Syria, issued a broadside. “From Russia’s first airstrikes in Syria, it has hit civilian areas and increasingly used indiscriminate weapons, including cluster and incendiary munitions. Its campaign has dramatically increased violence and prolonged the suffering of hundreds of thousands of civilians,” he said, blaming Russia for at least 2,700 civilian deaths. “Russia has proved to be either unwilling or unable to influence Assad and must bear its responsibility for the Assad regime’s atrocities.

America’s top diplomats, too, rail against Russia futilely. In a recently leaked recording of a meeting between a ham-handed but apparently sincere U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and members of the Syrian opposition, Kerry admitted that he lost the internal debate in the administration for greater intervention, more protection of civilians, and a stiffer stand against Russia’s triumphalist expansionism. But like a good soldier, he has continued to flog a bad policy, pushing perhaps much too hard on the small constituency of opposition Syrians who remain committed to a pluralistic, unified, democratic Syria.

Perhaps Russia has been searching for the West’s actual red lines all along, exploring how far it could go in Syria without provoking any push back from the United States and its allies. Maybe it finally found them after it bombed the UN aid convoy in September. Only time will tell if the recent pitched rhetoric translates into action.

One of the few consistent goals of U.S. policy in Syria over the last year was to shift the burden of responsibility for the crisis, or even guilt, to Russia. Throughout long negotiations, Washington has bent over backwards to act in good faith, trusting against all evidence that Russia was willing to act in concert to push Syria toward a political settlement. America’s leaders today appear shocked that Russia was acting as a spoiler, a fact clear to most observers long ago.

With the latest agreement in ashes—literally—and an ebullient Russia convinced it will encounter no blowback for its war crimes, America has a political chit in its hands. For now, Russia thinks it can achieve its strategic goals by relentlessly destabilizing the international order and lying as gleefully and willfully as the Assad regime. The United States helped underwrite that international order when the UN came into being in 1945, laying down moral markers on atrocities like genocide and war crimes, and crafting a web of interlocking institutions that increased global security and prosperity. As its primary enforcer, the United States also has been its primary beneficiary.

Now that Russia, determined to reestablish its status after the humiliating collapse of the Soviet Union, has pushed the United States into a humiliating corner and weakened that international order, it is raising the stakes. Either the United States will push back, or the disequilibrium will spread even further. In either case, many thousands more Syrians will perish. As Bassam Hajji Mustafa, a spokesman for the Nour al-Din al-Zinki Movement, one of the more effective, if violent, rebel militias influential around Aleppo, put it, “People have adapted to death, so scaring them with this siege is not going to work.” Those who remain in Aleppo echo this refrain again and again: The last holdouts have stayed out of conviction. It’s hard to imagine anything but death driving them out. “If Aleppo falls and the world stays silent, then that will be the end of the revolution,” Hajji Mustafa said.

In the end, Aleppo is not a story about the West; it is a cornerstone of Syria and an engine of wealth and culture for the entire Levant. Aleppo is the story of the willful destruction of a pivotal Arab state, a center of gravity in a tumultuous region in sore need of anchors. It’s a story of entirely avoidable human misery: the murder of babies, the destruction of homes, the dismantling of a powerful industrial and craft economy.

The institutions of global governance are under strain and international comity is frayed; as yet, however, none of the steps toward dissolution are irreversible. Such shifts take place over decades, not months. But the crisis in Syria presents the most acute test yet, and demands of the United States an active, robust, and strategic response that reinforces its commitment to the architecture of global governance—a system threatened by spoiler powers like Russia and ideological attacks from nativists, the right-wing fringe, and other domestic extremists in the West.

Ignoring its responsibilities in Syria—and opening the door for Russia to pound away at the foundations of the international order—hurts not only Syrians but the entire world. Perhaps, finally, Assad and his backers have gone far enough to provoke an American defense of that indispensable order that America helped construct.

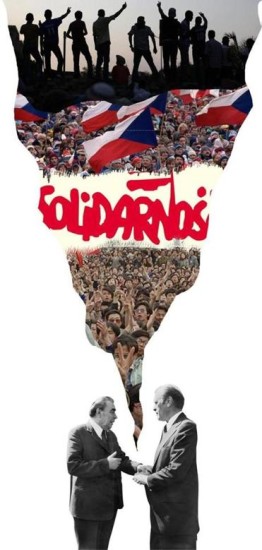

How a handshake in Helsinki helped end the Cold War

AP AND GETTY IMAGES PHOTOS; GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and President Gerald Ford met in Helsinki at the All European Conference on Security and Cooperation in July 1975.

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

EIGHT HUNDRED YEARS AGO this summer, King John and a group of feudal barons gathered at Runnymede on the banks of the Thames River. There he agreed to the Magna Carta, which for the first time limited the absolute power of the monarch and established a contract between ruler and ruled. The mother of modern treaties and law, the Magna Carta began a global conversation about the responsibility of the powerful toward people under their control.

A scant four decades ago, also this summer, another gathering in the Finnish capital of Helsinki produced a second series of accords. While far less well known, the signing of the Helsinki Accords was a critical juncture in the long struggle of the individual against state authority. Building on some of the same ideas that undergirded the Magna Carta, the Helsinki Accords codified a broad set of individual liberties, human rights, and state responsibilities, which remain strikingly relevant today, whether the subject is China’s Internet policy, the Islamic State’s latest outrage, or the American “war on terror.” The language of human rights has become the lingua franca for criticizing misbehavior by states or quasi-governments.

Today, most governments have signed on to the United Nations’ definition of universal human rights, only disagreeing about whether their own transgressions run afoul of them. Rights groups are ubiquitous, criticizing the treatment of American prisoners, Chinese sweatshop workers, Iranian dissidents, and other groups whose rights are abridged.

Yet for the widespread agreement that human rights represent shared, universal values, it’s still hard to predict when a campaign based on moral accusation can change the actions of a state. Indeed, the question is no longer whether human rights can make a difference, it’s whether they will in any particular case.

It wasn’t always so. Until recently, human rights were hardly part of the realpolitik discourse and were certainly not considered an effective cudgel against powerful regimes. That changed 40 years ago, when powers from both sides of the Iron Curtain signed the Helsinki Final Act and unwittingly ushered in the era of the human rights group.

Solidarity in Poland, Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, and the Moscow Helsinki Group played key roles in the fall of the Soviet Union. They galvanized public dissatisfaction at home, embarrassed their governments abroad, and catalyzed the Soviet bloc’s loss of legitimacy. Many historians now believe that the 1975 Helsinki Accords and the human rights movement they engendered played a pivotal role in ending the Cold War, far exceeding the humble expectations of the diplomats who brokered the agreement.

“The most important legacy of the Helsinki Final Act today is that citizens have the right to monitor and report on the human rights records in their own country,” said Sarah Snyder, a historian at American University who has written a book called “Human Rights Activism and the End of the Cold War.” Prior to 1975, groups like Amnesty International tried to create international pressure with letter-writing campaigns, usually from outside the country where an injustice was occurring. Snyder believes that Helsinki created a new paradigm of human rights and a global slate of organizations that pursued them, with lasting impact — all the more impressive, Snyder said, because Helsinki wasn’t a legally binding treaty. “The only way it was binding was morally,” she said.

Academics have given a name to the idea that human rights advocacy can change facts on the ground: “The Helsinki Effect,” also the title of a 2001 book by political scientist Daniel Thomas, which popularized the argument that human rights trumped geopolitics and economics in resolving the Cold War.

How did a nonbinding, lumbering bureaucratic agreement reached four decades ago spawn the modern human rights movement? And what’s left of the legacy of Helsinki?

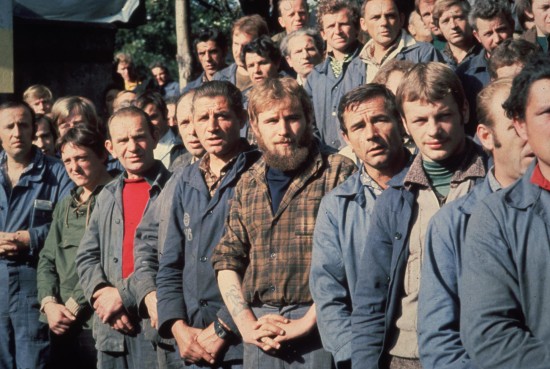

KEYSTONE/GETTY IMAGES

Members of the Polish trade union, Solidarity, on strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in August 1980.

AT THE HEIGHT of the Cold War, the Soviet bloc was a closed and inaccessible society. Many people who lived behind the Iron Curtain weren’t allowed to leave, and outsiders were permitted only tightly controlled, limited glimpses at life inside. The specter of cataclysmic conflict hung over East and West, with both sides brandishing thermonuclear and conventional arsenals that were unthinkably vast and destructive.

Throughout the Cold War, there were points of tension followed by periods of accommodation. The Helsinki Accords marked one of the latter. Relations across Europe had become so strained and so dangerous that Moscow, Washington, and all the capitals in between agreed there had to be some degree of relaxation. Both sides wanted to avoid a continental war between the superpowers. Both sides sought to end what they saw as belligerent expansion by the other.

They gathered in Helsinki on Aug. 1, 1975, to sign an agreement that turned out to be a seminal breakthrough — although not in the way that either side expected. The agreement signed by 35 states, including the United States and the USSR, focused for the most part on reestablishing respect for borders, national sovereignty, and peaceful resolution for future disputes between states. It also included a clause recognizing universal human rights, including freedoms of thought, conscience, and belief.

President Gerald Ford was castigated by his domestic critics for signing away the farm, because he had acknowledged Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, the Soviets trumpeted Helsinki as a tremendous victory, enshrining their sphere of influence and providing international legitimacy to their repression of citizens and governments in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and elsewhere. They were so unconcerned about the human rights provisions that they published the Helsinki Final Act in full in the pages of the state newspaper, Pravda.

Western diplomats had modest hopes that the personal freedoms enumerated at Helsinki would ease the way for Eastern Bloc spouses married to Westerners, and for cultural and academic exchanges that promoted international dialogue.

But the importance of Principle Seven became evident almost before the ink was dry. Civic groups sprung up across the Eastern Bloc, determined to exercise their right to monitor their own governments’ compliance with Helsinki. Andrei Sakharov, the famous Soviet dissident, oversaw the founding of the Moscow Helsinki Group at his apartment in 1976. Activist playwright Vaclav Havel helped set up Charter 77 in Prague the following year. A Helsinki watch group opened in Poland in 1979.

The watch groups became very public thorns in the side of Communist governments. Their leaders were well known domestically and had contacts in the West, particularly in the press. They mobilized global attention to the human rights abuses of the Soviet Union and its client dictators.

And when governments subjected the watch groups to withering pressure, the activists asked their supporters outside the Iron Curtain to establish a unified organization that could defend the Helsinki Watch monitors. Human Rights Watch, perhaps the best-known and farthest-reaching global rights advocacy group today, originated with the Helsinki Watch group founded in 1978.

A brilliant, if perhaps unintended, enforcement system was built into Helsinki. All the signatory nations agreed to reconvene regularly, and the 10-point document contained many items of great political and security import to the Soviet Union. If the Soviets wanted to keep the benefits of Helsinki, they’d have to put up with attacks on their human rights record at the follow-up meetings.

“Without this follow-up mechanism, I think there would have been a big celebration after the signing, and we never would have heard of the Helsinki Final Agreement again,” Snyder said.

Instead, a panoply of Eastern Bloc activists and their Western supporters flooded diplomatic confabs at Belgrade, Madrid, and Vienna with details about oppression and abuses. Often, the Helsinki monitors became celebrities themselves, drawing widespread attention when they were persecuted and detained by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies.

The Helsinki-inspired human rights movements put a face on government oppression and placed rights atop the Cold War agenda alongside arms control. To the frustration of Soviet leaders, the world became absorbed by the plight of jailed activists and refuseniks denied exit visas.

By time Mikhail Gorbachev took over the leadership of the Soviet Union in 1985, he couldn’t sidestep human rights concerns when he began to negotiate a full détente.

THE NAMING AND SHAMING techniques pioneered by the Helsinki monitors run deep in the DNA of contemporary human rights groups. “The mechanisms that were so essential to Helsinki remain a key tool of the human rights movement today,” said Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch. “How does the human rights movement get anything done? By shaming, and by enlisting powerful governments to act on behalf of victims of human rights violations.”

For decades after the ratification of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, human rights remained largely an abstract concept in world politics. Most governments agreed with the principle but comfortably ignored human rights in practice.

The crumbling of the Soviet empire gave the human rights movement both experience and legitimacy. The Berlin Wall came down, and Eastern Bloc countries toppled their homegrown dictators. Lech Walesa, head of the Solidarity trade union, was elected president of Poland. Vaclav Havel, a playwright and signatory of Charter 77, won the presidency of Czechoslovakia and worldwide renown as a highly cultured philosopher-king. A generation after the Helsinki monitors came to prominence as victims of tyranny, they had become the face of a new democratic political elite.

The changing values that elevated them have become part of the world’s political orthodoxy; even governments that routinely violate human rights still pay them lip service.

“Even North Korea is pretending to accept human rights,” Roth said. “Governments care about their reputation and don’t want to be seen as violating human rights norms.”

Authoritarian backlash is another legacy of the Helsinki era. Dictators have also studied the rise of the civic monitors, and concluded that groups like Human Rights Watch really could cause them problems. A common result has been to strike hard and quickly against human rights groups, especially when they are run by locals who have moral authority. Vladimir Putin’s rise to power has been accompanied by the silencing and killing of many credible rights monitors. Iran’s ayatollahs deployed maximal force to destroy the “Green Revolution” of 2009. Egypt’s dictatorship rails against any criticism of its human rights record as meddling and foreign interference, and prosecutes domestic rights group with the same zeal that it pursues armed antigovernment insurgents. Despotic regimes have made it common practice to starve rights groups of funding and deny them permits to operate.

Given the success of authoritarian regimes, not everyone is convinced that the Helsinki effect is as pronounced as its champions claim. Among the many commemorations scheduled for the 40th anniversary year, a group of scholars is gathering at the Sorbonne in Paris this December to explore how much the agreement and the human rights movements it created really were responsible for social and political change.

“My feeling is that we really don’t know that much, beyond generalities, that is, in terms of how the ‘Helsinki effect’ effectively operated by way of changing East European societies from within,” one of the organizers, Frédéric Bozo, a historian the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, wrote in an e-mail. He’s also not sure whether anything about the Helsinki era applies to today’s thorny nexus of human rights and political power — another area he said is ripe for further inquiry.

Skeptics of the narrative of human rights triumphalism point out that the US government always paid more attention to transgressions committed by its rivals than by its friends. That pattern continues today in Washington, with pointed human rights criticism of China, Russia, Cuba, and Iran. There’s far less enthusiasm in the West for documenting human rights abuses by allies like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel — or for that matter, addressing the plight of those held without trial at Guantanamo Bay or killed in drone strikes.

In some ways, the world was more binary during the Helsinki era. Two major superpowers dominated the world; if they agreed, most other nations fell into place. Nonstate actors hadn’t assumed their central role in international politics, with their destabilizing penchant for asymmetric warfare.

Even pessimists like Anne-Marie Le Gloannec, a political scientist at Sciences Po in Paris, admit that Helsinki produced an enduring change. Le Gloannec believes the world is headed for dark times, with resentment driving an anti-Western wave led by tyrannical demagogues like Russia’s Putin. The war in Ukraine could spread farther into Europe, she believes, and human rights norms won’t do anything to calm tensions.

Despite her grim forecast, Le Gloannec belives that civic and human rights are here to stay — thanks to Helsinki. “We have a new paradigm,” she said. “People have the right to defend their rights, to fight for their rights.” However fragile, it’s a paradigm that for the first time placed individuals, rather than nation states, at the center of international relations.

What line did Putin cross in Crimea?

[The Internationalist column published in the The Boston Globe Ideas.]

WHAT HAPPENED IN UKRAINE over the past month left even veteran policy-watchers shaking their heads. One day, citizens were serving tea to the heroic demonstrators in Kiev’s Euromaidan, united against an authoritarian president. Almost the next, anonymous special forces fighters in balaclavas were swarming Crimea, answering to no known leader or government, while Europe and the United States grasped in vain for ways to influence events.

Within days, the population of Crimea had voted in a hastily organized referendum to join Russia, and Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, had signed the annexation treaty formally absorbing the strategic peninsula into his nation.

As the dust settles, Western leaders have had to come to terms not only with a new division of Ukraine, but its unsettling implications for how the world works. Part of the shock is in Putin’s tactics, which blended an old-fashioned invasion with some degree of democratic process within the region, and added a dollop of modern insurgent strategies for good measure.

Vladimir Putin at the Plesetsk cosmodrome launch site in northern Russia./PRESIDENTIAL PRESS SERVICE VIA REUTERS

But when policy specialists look at the results, they see a starker turning point. Putin’s annexation of the Crimea is a break in the order that America and its allies have come to rely on since the end of the Cold War—namely, one in which major powers only intervene militarily when they have an international consensus on their side, or failing that, when they’re not crossing a rival power’s red lines. It is a balance that has kept the world free of confrontations between its most powerful militaries, and which has, in particular, given the United States, as the most powerful superpower of all, an unusually wide range of motion in the world. As it crumbles, it has left policymakers scrambling to figure out both how to respond, and just how far an emboldened Russia might go.

***

“WE LIVE IN A DIFFERENT WORLD than we did less than a month ago,” NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen said in March. Ukraine could witness more fighting, he warned; the conflict could also spread to other countries on Russia’s borders.

Up until the Crimea crisis began, the world we lived in looked more predictable. The fall of the Berlin Wall a quarter century ago ushered in an era of international comity and institution building not seen since the birth of the United Nations in 1945. International trade agreements proliferated at a dizzying speed. NATO quickly expanded into the heart of the former Soviet bloc, and lawyers designed an International Criminal Court to punish war crimes and constrain state interests.

Only small-to-middling powers like Iran, Israel, and North Korea ignored the conventions of the age of integration and humanitarianism—and their actions only had regional impact, never posing a global strategic threat. The largest powers—the United States, Russia, and China—abided by what amounted to an international gentleman’s agreement not to use their military for direct territorial gains or to meddle in a rival’s immediate sphere of influence. European powers, through NATO, adopted a defensive crouch. The United States, as the world’s dominant military and economic power, maintained the most freedom to act unilaterally, as long as it steered clear of confrontation with Russia or China. It carefully sought international support for its military interventions, even building a “Coalition of the Willing” for its 2003 invasion of Iraq, which was not approved by the United Nations. The Iraq war grated at other world powers that couldn’t embark on military adventures of their own; but despite the irritation the United States provoked, American policymakers and strategists felt confident that the United States was obeying the unspoken rules.

If the world community has seemed bewildered by how to respond to Putin’s moves in Crimea over the last month, it’s because Russia has so abruptly interrupted this narrative. Using Russia’s incontestable military might, with the backing of Ukrainians in a subset of that country, he took over a chunk of territory featuring the valuable warm-water port of Sevastopol. The boldness of this move left behind the sanctions and other delicate moves that have become established as persuasive tactics. Suddenly, it seemed, there was no way to halt Russia without outright war.

Some analysts say that Putin appears to have identified a loophole in the post-Cold War world. The sole superpower, the United States, likes to put problems in neat, separate categories that can be dealt with by the military, by police action or by international institutions. When a problem blurs those boundaries—pirates on the high seas, drug cartels with submarines and military-grade weapons—Western governments don’t know what to do. Today, international norms and institutions aren’t configured to react quickly to a legitimate great power willing to use force to get what it wants.

“We have these paradigms in the West about what’s considered policing, and what’s considered warfare, and Putin is riding right up the middle of that,” said Janine Davidson, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former US Air Force officer who believes that Putin’s actions will force the United States to update its approach to modern warfare. “What he’s doing is very clever.”

For obvious reasons, a central concern is how Putin might make use of his Crimean playbook next. He could, for example, try to engineer an ethnic provocation, or a supposedly spontaneous uprising, in any of the near-Russian republics that threatens to ally too closely with the West. Mark Kramer, director of Harvard University’s Project on Cold War Studies, said that Putin has “enunciated his own doctrine of preemptive intervention on behalf of Russian communities in neighboring countries.”

There have been intimations of this approach before. In 2008, Russian infantry pushed into two enclaves in neighboring Georgia, citing claims—which later proved false—that thousands of ethnic Russians were being massacred. Russia quickly routed the Georgian military and took over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Today the disputed enclaves hover in a sort of twilight zone; they’ve declared independence but were recognized only by Moscow and a few of its allies. Ever since then, Georgian politicians have warned that Russia might do the same thing again: The country could seize a land corridor to Armenia, or try to absorb Moldova, the rest of Ukraine, or even the Baltic States, the only former Soviet Republics to join both NATO and the European Union.

Others see Putin’s reach as limited at best to places where meaningful military resistance is absent and state control weak. Even in Ukraine, Russia experts say, Putin seemed content to wield influence through friendly leaders until protests ran the Ukrainian president out of town and left a power vacuum that alarmed Moscow. Graham, the former Bush administration official, said it would be a long shot for Putin to move his military into other republics: There are few places with Crimea’s combination of an ethnic Russian enclave, an absence of state authority, and little risk of Western intervention.

The larger worry, of course, is who else might want to follow Russia’s example. China is the clearest concern, and from time to time has shown signs of trying to throw its weight around its region, especially in disputed areas of the South China Sea. But so far it has been Chinese fishing boats and coast guard vessels harassing foreign fishermen, with the Chinese navy carefully staying away in order not to trigger a military response. For the moment, at least, Putin seems willing to upend this delicately balanced world order on his own.

***

THE INTERNATIONAL community’s flat-footed response in Crimea raises clear questions: What should the United States and its allies do if this kind of land grab happens again—and is there a way to prevent such moves in the first place?

“This is a new period that calls for a new strategy,” said Michael A. McFaul, who stepped down as US ambassador to Russia a few weeks before the Crimea crisis. “Putin has made it clear that he doesn’t care what the West thinks.”

So far the international response has entailed soft power pressure that is designed to have an effect over the long term. The United States and some European governments have instated limited economic sanctions targeting some of Putin’s close advisers, and Russia has been kicked out of the G-8. There’s talk of reinvigorating NATO to discourage Putin from further adventurism. So far, though, NATO has turned out to be a blunt instrument: great for unifying its members to respond to a direct attack, but clumsy at projecting power beyond its boundaries. As Putin reorients away from the West and toward a Greater Russia, it remains to be seen whether soft-power deterrents matter to him at all.

Beyond these immediate measures, American experts are surprisingly short on specific suggestions about what more to do, perhaps because it’s been so long since they’ve had to contemplate a major rival engaging in such aggressive behavior. At the hawkish end, people like Davidson worry that Putin could repeat his expansion unless he sees a clear threat of military intervention to stop him. She thinks the United States and NATO ought to place advisers and hardware in the former Soviet republics, creating arrangements that signal Western military commitment. It’s a delicate dance, she said; the West has to be careful not to provoke further aggression while creating enough uncertainty to deter Putin.

Other observers in the field have made more modest economic proposals. Some have urged major investment in the economies of contested countries like Ukraine and Moldova, at the scale of the post-World War II Marshall Plan, and a long-term plan to wean Western Europe off Russian natural gas supplies, through which Moscow has gained enormous leverage, especially over Germany.

Davidson, however, believes that a deeper rethink is necessary, so that the United States won’t get tied up in knots or outflanked every time a powerful nation like Russia uses the stealthy¸ unpredictable tactics of non-state actors to pursue its goals. “We need to look at our definitions of military and law enforcement,” she said. “What’s a crime? What’s an aggressive act that requires a military response?”

McFaul, the former ambassador, said we’re in for a new age of confrontation because of Putin’s choices, and both the United States and Russia will find it more difficult to achieve their goals. In retrospect, he said, we’ll realize that the first decades after the Cold War offered a unique kind of safety, a de facto moratorium on Great Power hardball. That lull now seems to be over.

“It’s a tragic moment,” McFaul said.