Muslim Brotherhood goes legal

My latest column in The Atlantic considers the turning point reached this week when the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party gained official recognition.

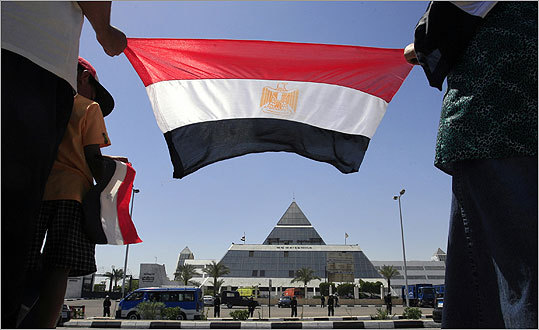

CAIRO, Egypt — This Tueday, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood became a legal political party for the first time since President Gamal Abdel Nasser banned it more than half-a-century ago. The military officers managing Egypt’s transition out of the Age of Mubarak approved the Brotherhood’s new Freedom and Justice Party, the Islamist organization’s chosen vehicle to political power.

After decades in limbo, the Muslim Brotherhood will now have all the benefits of unambiguous legal status — and face all the scrutiny and questioning to which a political behemoth is subjected. The Brotherhood has built its considerable following, and honed its impressive organizational wherewithal, by striving in the shadows against a police state’s full force.

During their decades under the ban, Brothers spread their religious message and delivered what services they could. Now, however, the challenges are vast and political, and the underground methods of a doctrinaire religious group (whose primary mission, always, was spreading a strict message of faith) won’t play the same way on the political stage.

It’s a confusing transition for the Islamist activists trying to reposition their organization from oppressed social group to political strongman.

Egypt on the John Batchelor show

John Batchelor asks me about Egypt’s constitutional debate on his show; clip starts just after the 19:00 mark.

Now What?

In The Boston Globe I write about the competing schools of thought over what Egypt’s next government should look like. This debate will only get more complicated as the year wears on, with different philosophies vying for predominance on the surface, while powerful and silent vested interests struggle for power below.

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”

The Shiny New Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brothers hosted their grand coming-out party on Saturday night. Officially, the occasion marked the opening of their new headquarters, a seven-story monstrosity that looks like an egg-cream ziggurat on a breezy plateau above Islamic Cairo. Unofficially, the event was a declaration that the Brothers have arrived and will be kingmakers during Egypt’s season of political change.

“We’re not banned anymore,” exulted Mohsen Radi, who served a turn in parliament as a representative of a Delta town called Banha. “By the grace of freedom, by the grace of the revolution, we have regained our place.”

As symbols go, the building and its inaugural could not have been more potent. For decades, the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide operated out of a stuffy, dark, low-ceilinged apartment on the isle of Manial, in Cairo’s center. A team of state security men loitered out front. Entering visitors had to clamber over the pile of shoes in the hallway, between the elevator and the door. Senior officials would conduct interviews in the corner of the same room where the rest of the leadership was deliberating.

It was, to say the least, a no-frills operation, highlighting the Brotherhood’s ambiguous status as a legally prohibited but semi-tolerated organization.

Between 2005 and 2009, when the Brothers held 88 parliamentary seats, the organization opened a slightly more spacious parliamentary office nearby. State security forbade them from organizing any large public events, and even their annual Ramadan iftaar was cancelled. During functions there, the power often mysteriously cut out, with a frequency that the Brotherhood accepted as one of the more petty manifestations of state harassment.

Now, however, the Brotherhood is freely exercising its organizational muscle. Since Mubarak was run out of office, the Muslim Brotherhood has opened offices in every province. It is launching its own satellite television network. It has entered coalition talks with other groups, and has founded its own political party, called Freedom and Justice, which has a Christian vice president. At first, in an effort to comfort worried Christians and secularists, the Brotherhood said it would contest only 30 percent of the seats in parliament, and wouldn’t run a presidential candidate. Last week, it raised the ante, now saying it will compete for half the parliamentary districts.

With the opening of the new official headquarters in Moqattam, the transformation is complete. Bright lights illuminate the party logo in English and Arabic – a pair of green crossed swords.

About a hundred movement activists prayed outside before the official opening on Saturday night (the building’s been in use for weeks already). They chanted the Brotherhood motto in unison:

God is great.

The Prophet is our teacher.

The Koran is our constitution.

Jihad is our way.

Martyrdom is our goal.

Then they stormed into the building and emptied trays of fruit juice.

In a sign of the Brotherhood’s political heft, a parade of notables came to pay respects, including presidential front-runner and former Arab League chief Amr Moussa and a coterie of other secular politicians and judges.

In a rear lot behind the headquarters, more than a thousand supporters assembled in a dirt lot covered with carpets for the occasion. A band sang paeans to freedom, brotherhood, and the Brotherhood.

Khairat Shater, a millionaire and number-two official in the Brotherhood credited with being one of its most powerful fixers, grinned just beside the stage.

“Where do you think state security is now?” I asked. At the last Brotherhood function I attended, an iftaar in the parliamentary offices in August, the number of plainclothes intelligence officers hovering around the event equaled that of the Brotherhood officials inside.

“They haven’t gone home,” he said. “They’re around here somewhere.”

If one were keeping score, however, the Brotherhood would look to be ahead.

The Youth of the Revolution

I’ve been in Egypt covering the referendum and the latest twists of the revolution — a juicy and suspenseful saga, although one easily overlooked as the entire world rises up or melts down, gets bombed or washed away. One reason I’ve not been posting my reporting live is the size of my traveling party, which includes Anne and two quite young tourists, pictured above at the Giza pyramids today.

Michael Hanna on Egypt

Michael Hanna at The Century Foundation has a smart oped in The Christian Science Monitor about the steps necessary to translate Egypt’s revolution into lasting reforms. He argues that the rushed timeline imposed by the military might thwart the systemic changes needed to institute a credible constitution and initiate electoral politics.

Michael Hanna at The Century Foundation has a smart oped in The Christian Science Monitor about the steps necessary to translate Egypt’s revolution into lasting reforms. He argues that the rushed timeline imposed by the military might thwart the systemic changes needed to institute a credible constitution and initiate electoral politics.

Progress based solely on a hasty electoral transition would be an illusion – which might undercut efforts at real reform. Instead of accepting a transition process implemented and dictated solely by the armed forces,Egypt’s opposition should remain united in seeking immediate actions that will preclude diversion to military-led governance, while allowing for a more realistic transitional period.

The country’s opposition groups are keen to ensure that the armed force’s custodianship is, in fact, temporary, and not a prelude to consolidation of a revamped, military-led regime. This concern – and broader and well-justified concerns about a counter-revolution – are understandable based on Egypt’s history and recent developments. Yet, these very same concerns could lead to support for a transition process that will actually undermine the core goals of the Egyptian uprising and subvert thorough reform. A six-month timetable for popular elections, as was announced by the Egyptian military, will dictate that reform in the interim period will be shallow and that even free and fair elections will not be an opportunity for true representational politics. Read the rest here.

We had a panel discussion at The Century Foundation last week where we discussed some of the implications of the revolution for Egypt going forward and for the Arab world as a whole. My favorite part of the evening came when the Yemeni ambassador to the U.N. Abdullah Al-Saidi diagnosed the central problem of the region as “leaders who have tried to transform republics into monarchies” — a malady from which he did not exempt his own country (you can watch the q & a here). That’s a fair enough way to summarize the ills of regimes in Yemen, Egypt, Libya, and Syria. It doesn’t address the failure to govern, which is at root what plagues all the Arab states, including those that are avowedly hereditary monarchies (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco). You can watch the event at The Century Foundation here.

Resistance and Revolution

In the weeks since I returned from Egypt, I’ve made a number of previously scheduled talks, originally intended to cover Hezbollah and the most recent developments in Lebanon. I’ve made a stab at addressing the tumultuous change more broadly, as three forces are now competing for popular momentum: revolution (the massive and ongoing regional wave), reaction (the old statist regimes and monarchs), and resistance (the axis of empowerment through armed uprising).

It appears that Salve Regina, the small college in Newport, R.I. that hosted one of those talks, has posted the video online. It is with some trepidation that I post the link.

Some Lessons of the Arab Revolts

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I explore some of the implications of the Arab revolutions for US policy. It will take a long time for American policy makers to grasp the implications of the popular wave sweeping the Arab world, and if history is any guide, the architects of American policy might never actually figure out what happened, why, and how best to respond. One of my favorite analysts and bloggers, Issandr El Amrani at The Arabist, thinks the arguments I make are at best banal, at worst, completely wrong-headed.

Here’s how the column opens:

The popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and beyond have seized the world imagination like no events since the collapse of the Iron Curtain. Regimes are teetering, dictators have fallen, and unexpected coalitions have managed to conjure street-level power seemingly out of thin air. Tunisians took credit for Egypt’s revolution; Egyptian demonstrators in turn claim they inspired people in Wisconsin and Bahrain.

Much remains uncertain, and even the most experienced observers have no idea who will hold power in the aftermath of these uprisings. But already we’ve learned more in a few short months than we gleaned from decades of careful study about the real power base of Moammar Khadafy and Hosni Mubarak, about the balance among armies and tribes, about the relative power of secular and Islamist activists. We’re seeing the true measure of oil money and the Muslim Brotherhood, of popular anger about corruption, and of the real interest in economic liberalization.

But perhaps the most surprising lessons emerging from all the unrest are even bigger ones — insights that extend well beyond the Middle East, and are forcing thinkers and policy makers to reconsider some basic assumptions that have long guided America’s foreign policy. How much impact can America really have on world events? How do our alliances function at crucial moments? Who really has the potential to initiate and control massive change in modern societies? The surprising answers suggested by the Arab revolts might create new options in the minds of American policy makers looking to advance not only US security and economic goals, but also the causes of human rights, transparency, and democratic governance.

The Gamble for Egypt’s Future

The Atlantic has posted my essay about the next gamble for Egypt’s revolutionaries: Can they sustain pressure on the ancien regime?

The euphoria in Cairo already is already giving way to anxiety as Egyptians contemplate the terrifying task of dismantling Hosni Mubarak’s police state and building an accountable Arab democracy in the image of Tahrir Square.

The old order has been decapitated, but still exerts an undeniable gravitational pull over the entire polity. Thousands or possibly millions of policemen, informants, and clients of Mubarak’s state tremble at the prospect of transparency and, perhaps, retribution. If the protesters want to pursue reform, they will have to consider, and maybe even accommodate, those remnants of the old order.

On the morning before Mubarak resigned, I sat poolside with a group of retired generals at the Gezira Club, a members-only holdover of colonial times. A recently retired general from state security tried to interrogate me about the demonstrators; he was still convinced, against all evidence, that it was a Muslim Brotherhood uprising. The police, he was certain, would soon regain control of the nation. “How will the police regain public trust when they are so hated?” I asked. He couldn’t fathom what I was saying. “The majority of people love the police,” he shouted at me. “They will respect the police because they need the police.”

Old Egypt was on display elsewhere as well, in the patronizing and impatient tone in which the prime minister addressed the public in his first press conference after Mubarak’s downfall, in the capricious manner with which soldiers turned away some people at checkpoints while allowing others to pass, in the air of disgust with which some of Egypt’s millionaires, talking to me over cocktails at the Bodega Bar the day after Mubarak’s abrupt disappearance, dismissed the revolution as a failure that would usher in an anti-business government.

The revolutionaries, gambling as they have every step of the way, have gone for broke and demanded complete systemic reform: a new constitution written from scratch and an interim government purged of the Mubarak family and their Cardinal Richelieu, the spymaster and momentary Vice President Omar Suleiman. Perversely, though, the only way toward that goal was another, bigger, gamble: the revolutionaries have asked a military dictatorship to manage the transition in the hope that a committee of unelected generals who have spent a career defending Mubarak’s order will now willingly write themselves out of power.

The prospect may sound crazy, naïve, even delusional – but then again, three weeks ago so did the possibility of millions of Egyptians embracing civil disobedience and successfully castrating the Mubarak regime.

‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’

Egypt’s revolutionaries suspect the ecumenical and utopian nature of their wave will bless the next phase of their struggle. So many of the people I talked to on the streets today – before and after Mubarak skulked to his summer palace – already were busy imagining a future in their own indigenous vernacular. Mubarak’s cruelty drove them into a frenzy of rage, but once released from their state-induced torpor and timidity, they found themselves more interested in screaming about the things they wanted, rather than the things they wanted to get rid of.

Mubarak was a spark but also a footnote.

“He treated us all as if we were stupid,” said Leila Abdelbar, a staffer on parliament’s foreign affairs committee. “He underestimated us. He should have respected us.” She was angry, at a father who didn’t take his own children seriously. She also was angry at herself, for having acted for so long like she believed him.

“We have to thank our children for showing us the way,” she said, looking with adoration at her daughter Heba.

She and her friends are conservative Muslims, some of them wearing the full-face covering niqab. They’re not in the Muslim Brotherhood and they’re not interested in an Islamic state; they spoke with longing about a new constitution, a reconstituted judiciary, and a state that provided basic rights: rule of law, education, health and safety.

No one in the crowd used the American democracy vocabulary. They spoke with organic idioms, conjuring huriya, liberty, based on citizens who took their own rights, rather than received them as a leader’s prerogative. “We will take our rights,” many people repeated; they meant that they would demand a new compact, in which they would articulate their needs and if those needs went unmet, they would remake their state.

The specifics varied, and some people still drifted in vague hope for something better. Some talked of their right not to be arrested at will by unaccountable secret police. Some yearned for better schools and hospital care for the poor.

Protest leaders feted the moment but kept planning. “We’ll work until the last moment,” said Basem Kamel, one of the leaders of the Baradei civil reform campaign. Youth leaders were meeting at 1 a.m. to coordinate a clean withdrawal from the square and set negotiating terms for their discussions with the army (Kamel is 41 and balding, but youth is also a state of mind).

I have no doubt there will be reversals ahead, but Egypt has written a new chapter in modern history with utter disregard for all expectations for the contrary – their own as well as those of outsiders. There’s every reason to hope that the same millions of Egyptians who drove a tyrant to flee without firing a shot and without calling for the destruction of anything, and who discarded all their traditional corroded institutions to invent a unified popular front, might now manage the parlous task of writing a new constitution, convincing the military to abdicate to a truly civilian order, and crafting a polity dedicated to serving its own citizens’ conception of their right to justice, liberty and security.

“We did it,” Ziad Al-Alaimy said after lifting me off the ground in a bear hug. “Tomorrow belongs to us.”

It’s a long road ahead, surely, but as many people said: Egypt has learned the way to Tahrir Square. They won’t soon forget it, and let’s hope, neither will their new leaders.

No End in Sight

On Thursday night in Tahrir Square, the crowds were convinced that Mubarak was about to deliver his resignation speech. Generals had told the crowd that on this day, their demands would be met; the high command had convened without Mubarak; and the head of the ruling party had demanded Mubarak amend the constitution and immediately resign.

Activists had already started discussing transitional governments, and warning the military against getting too comfortable. “We now know the way to Tahrir Square,” said Ahmed Sleem, 25, an activist. “We know how to force the military to stay down.”

Ayman Fareh, a tour guide whose son just turned one Ayman, 35, said he had prayed his son would not live another year under Mubarak, and he felt God had listened. “I was just born today,” he exulted. “There was a wall of terror, and it is broken. It will never be built again. We’ll never go back to this dark age. Tahrir Square is always here.”

The celebration turned out to be premature.

By the time Mubarak had made clear he intended to stay in office until September, angry shouts had broken out and thousands had removed a shoe and held it silently, stone-faced up to the screen where the president’s face was projected.

Ahmed Mohammed, 19, a computer student, shouted over Mubarak’s speech. “He will dig his grave himself,” he said, pumping his fist in anger. “He will get our answer tomorrow.”

Nearby other men chanted “He wants blood!”

Organizers warned darkly that violence was now inevitable. “He set the country on fire,” said Ziad Alaimy, one of the organizers. “No one can control the violence tomorrow. Tomorrow I think a lot of people will be killed.”

The dark mood abated within an hour. After midnight, the crowd at Tahrir was still booming at a time when it normally has thinned out to the most dedicated. Men in headbands led chants and songs. Hawkers at the exits entreated those who left to return on Friday.

People heatedly debated whether protesters would be able to take over the state television headquarters or presidential palace, and considered the merits of other ministries.

“Only God can decide what will happen tomorrow – not America, not Israel and not Hosni Mubarak,” screamed, Abdou Shinawi, 27, a perfume merchant, vowing to sleep in the streets until Mubarak left office. “Martin Luther King changed America with thousands of people. We have millions.”

Late in the night, thousands of people poured past the concrete barriers to demonstrate – and set up camp – in front of the Stalinist state television headquarters, an imposing circular tower on the Nile that looks like a fortress even in normal times. Thousands more were on their way to the presidential palace in Heliopolis.

“I wish that it continues to be peaceful,” said Ahmed Abdrabo, 22, a short story writer, grinning at a member of the presidential guard in full riot gear standing two arms’ lengths away, on the other side of a barbed wire fence. “We don’t want it to be transformed into a violent revolution. Tomorrow will not be a good day for Egypt.”

Karma

The lady who answered the Turkish Airlines number at the airport sounded unexpectedly solicitous. Perhaps because I’d just been decked with an unscrupulous $540 data roaming charge from AT&T (their mistake), I was especially charmed.

“I will not charge you to change your ticket even though I am supposed, because you have to Egypt in such a dangerous time,” she said expansively, after a long friendly chitchat.

“Thank you,” I said, genuinely warmed by the gesture.

Then her tone changed. “Unless you’re a journalist,” she said.

Silence.

“You’re not a journalist, are you?” she pressed.

“What if I were?” I said with a short forced laugh.

She chose to interpret my answer as a no, and issued my new ticket home.

Battle of Wills

The Atlantic has posted my dispatch about last night’s expansion of the Cairo protest to the gates of parliament:

On Tuesday, the revolutionaries in Tahrir Square took over the street in front of Parliament and the building where the presidential cabinet meets. A professors’ march took a few unplanned turns, joined a small group of protesters already in front of parliament, stragglers accrued, the military stood aside and – presto – the revolution had another beachhead.

By 10 p.m., hundreds of reinforcements streamed in from Tahrir Square, just around the corner, bringing blankets and tents. They were there to stay.

A government engineer sat smiling on the curb in front of parliament. Beside him a crowd whistled, cheered and beat a drum while a man shimmied up the iron gates of parliament. The sign he taped there read: “Closed Until the Fall of the Regime.”

“The government said we were just squatting in Tahrir Square having a picnic, so we had to move,” said the engineer, whose name was Tarek. At first he declined to tell me his last name, but then he laughed at the absurdity; he’s already on wanted list, and has been warned that if he goes to work at his government job, he’ll be arrested.

“If this revolution fails, Mubarak will hang me by my neck whether or not you publish my name,” Tarek said.

Organizers of Tahrir Square are playing a numbers game. If more people show up each time they call for a big crowd – as happened on Tuesday, which drew perhaps the greatest amount of people since it all began on January 25 – then the revolution advances. That’s their gamble. Several of them said they believe that success required steady escalation. Tuesday, the parliament. Friday, perhaps the state television headquarters or a ministry. Sunday, the police headquarters. And so on. They are hoping to organize major days of action three times a week, a plan that hinges on drawing more and more people each time. So far, popular response has exceeded their expectations at each turn. That’s no guarantee that the pattern will continue, or that the regime won’t use incalculable brute force or brilliant political maneuvering to shift the power balance.

The ultimate wild card is the Egyptian people. Many outside Tahrir Square complain about the demands of the people inside, which many see as too radical, and say they long for business as usual — especially now that Mubarak has promised to resign before the year’s end.

Talking Egypt on The World

Anchor Lisa Mullins interviewed me on Tuesday about the day’s protests in Tahrir Square. You can listen to our conversation here.

Four Scenarios

Last week Mohamed Rifaah al-Tahtawi resigned as spokesman for Al-Azhar, the seat of the Sunni clerical establishment in Cairo. Mohamed Rifaah is twice over an establishment figure. He spent a career in the foreign service as an ambassador and deputy to the foreign minister; after retirement in December 2009, he moved to the office of the grand sheikh of Al-Azhar.

“This youth movement changed our horizon. I didn’t expect it. I underestimated it,” Mohammed Rifaah told me, explaining his decision to renounce his job and join the revolutionaries. “This is a time to take sides, and I have taken sides.”

He invited me to join him on the curb in an alley off Tahrir Square, behind the makeshift hospital. “Welcome to my office,” he joked. “We are all revolutionaries now.”

He outlined four possible scenarios for the current political standoff:

- Soft transition. Under pressure from the United States and from regime insiders, Mubarak passes power to a more palatable member of the establishment and makes real, but incomplete, reforms to the system. Egypt’s foreign policy would remain unchanged.

- Tahrir Square becomes Hyde Park. The revolutionaries lose their connection to society at large and are allowed to continue their protest, but with marginal impact. The regime wins a war of attrition, and returns “with all its savagery, to take its revenge.”

- Tiananmen Square/Paris Commune. The regimes wipes out the protesters and faces no wider nationwide revolt in response.

- Radicalization. The regime gives no ground and in response the revolutionaries resort to force. The regime falls, along with the system it has built, and is replaced by a popular government after a destructive confrontation.

There are surely other scenarios, but Mohamed Rafaah’s breakdown of the alternatives is instructive. In his view, time does not necessarily favor the regime.

Keeping Score

In a sign of how quickly assessments shift, I’m looking here at my notes from yesterday. Thirty hours ago activists in the square were on the defensive, convinced the state had reconstituted and had them on the run. By noon today they were triumphant, and Tahrir Square was so clogged with people it took an hour to walk across it at times.

Here was the grim scene from Monday, when all seemed lost (to some, for a moment).

The world outside the square intruded only sporadically. Undercover intelligence officers circulated filming people with their cell phones, and streams of newcomers walked over the bridge in the afternoon to see if the activists were as bad as they had heard on state television.

“Are they giving out free cell phones?” asked a young math teacher named Fareed, who refused to give his full name and said it was his first, and probably last, visit to the demonstration.

State television has been broadcasting various untruths about the demonstrators, including claims that they receive money and free fast food. “Where is my Kentucky Fried Chicken?” has become a rallying cry for the people staying in the square.

By late afternoon on Monday the numbers inside the square were as high as the previous day, but core activists worried that for every Egyptian attracted for the first time to Tahrir, ten more were being turned off by state propaganda.

“I spend entire nights arguing with my family and posting on Facebook. They have started to turn against the protests,” said Mona Rabie, 28, a human rights worker. Most of her family members dismiss the protesters as radical, although a few have said they would like to take part but fear government punishment. One of her cousins said she was interested in visiting Tahrir but only if Mona would escort her past the military checkpoints. By late evening though she hadn’t arrived. “She’s hesitating. She’s got cold feet,” Mona said. “I think the only way is if I physically go to her house and drag her here.”

“For a while the tide of fear had turned, but it’s started to come back,” Mona said. “The government has too much muscle. I think the people are going to turn against the protesters. They’ve already started.”

She told her uncle that at least a hundred dead had been taken to one Cairo hospital and she had spoken directly with the doctor in charge of the morgue. He didn’t believe her. “If it were true, they would have told us about it on television,” he told Mona.

Still, though, new reinforcements had joined the hard inner core of protesters, spurred on by footage of the violent clashes Wednesday night between government-orchestrated thugs and the Tahrir protesters.

Abdulrahman Mohammed, 34, came to Tahrir for the first time on Monday. “I saw these people on television, and I realized they were better than me,” he said. It was the first time he had joined a protest. “Democracy has a price, and that price is blood.”

Mukhabarat in the Square

The secret police in Egypt usually aren’t very secret. They wear a certain recognizable cut of shabby pants, button-up shirts meant to hang untucked over the belt, and depending on rank a wide-weave sweater or shiny leather jacket.

In Tahrir Square, they parade with the crowds, ostentatiously filming everyone with their cell phones. Some activists who have been arrested and released since January 25 told me their interrogators reference films of them from Tahrir.

No one in the square seems to pay them any mind.

I found this indifference mystifying. Why weren’t the people in Tahrir trying to purge the place of infiltrators, as they had in early days? One organizer explained that there were simply too many, and that it only mattered if they tried to provoke fights. Otherwise, they caused no harm.

Helmy Hassan, a carpenter with no living family members to care for, offered a more compelling explanation. He spends his nights guarding a spur street leading to the square. “The revolution needs people like me,” he said. “That’s why we’re strong. Someone who needs to support his family can be bribed with money.”

Helmy said the scores of people circulating the square, filming with cell phone cameras, couldn’t intimidate demonstrators. “The video is a double-edged sword,” he said. “In the best case, they show the films to their friends and they see what we’re doing. In the worst case, they give the films to state security, and they see that I am defending my country. Let them. It is an honor.”

Under the tanks

At the northern end of Tahrir Square, by the National Museum, groups of men sleep in shifts beneath the treads of the army tanks that mark the northern perimeter of Revolutionary Egypt. Demonstrators allowed the tanks so the army could protect the antiquities in the museum, and ever since the army has tried to move them further.

It’s a particularly tough – and diverse – group of men crammed in close quarters beneath the treads. I talked at length to a doctor from Cairo, a primary school teacher from rural Upper Egypt, and a microbus driver from Giza. They break class and religious barriers, and they have profoundly absorbed the ethos of a new Egypt.

Saif Eldeen, 29, a primary school English teacher, joined the protest on Thursday morning, traveling from his home in Sohag, Upper Egypt. He lied to his wife, telling her he had to file some government paperwork, and drove to Cairo. She wept when he called her from Tahrir Square. “She said, ‘You want to leave me and your three-month old baby to die?’ I told her, ‘God will provide.’”

Saif spoke with a gleam in his eye – common to many of the most dedicated protesters – and said he no longer had anything to lose, and therefore, no incentive to compromise: “If we lose, I will spend the rest of my life in prison, or I will be killed.”

He sported a pronounced prayer bump and a grimy dress shirt. He brought no change of clothes, and planned to stay until the government fell or wiped out the protesters.

Beside him sat the microbus driver from Giza with his three-year-old daughter in his lap. “I come when I can afford not to work,” said the driver, Gamal Moghawery ElShimi, 36. Like many of the dedicated protesters, he worried that the silent majority of Egyptians consider the protests a nuisance or worse. Most of his relatives found the entire protest distasteful, and discouraged him from attending. “They think I’ll end up in prison and it’s not worth it,” Gamal said. “I try to change their minds, but mostly they are unconvinced.”

He wiped his daughter’s nose with a kerchief. He said he brought her along despite the risk so that she would not grow up to live like her parents. “I want her to see and feel what it’s like to defy authority,” he said.

(In the bottom picture, Saif is seated on the left, and Gamal and his daughter on the right.)

The Deep State

Out after curfew again on Sunday night (this time, though, only 9 p.m.) I was returning home after a long day talking to protestors. Plainclothes men frantically waved down my taxi at a joint army-police-neighborhood checkpoint when they saw my foreign-looking face (they looked like police trying to dress like civilians, in a style instantly recognizable as mukhabarat undercover). “Journalist?” they asked. “Camera?”

While a soldier affably thumbed through my passport, a police intelligence officer strode over and emitted a theatrical sigh. “You are coming from Tahrir Square?” he said. “You should know that not everyone in Egypt supports them. We are 80 million people. 1 million cannot make the decisions for us all.”

The soldier, who looked half the intelligence man’s age, interrupted the soliloquy about Egypt’s put-upon security state.

“You can go,” he said, with a smile that struck me as far more sincere than his colleague’s.

Foreigners

The soldiers had emptied our luggage onto the street and pulled apart the seats of our taxi. The driver was muttering angrily: “You don’t have to destroy my car.” It was four in the morning on Saturday and Cairo was under curfew, but we had decided to risk the checkpoints rather than wait at the airport until dawn.

The soldiers had emptied our luggage onto the street and pulled apart the seats of our taxi. The driver was muttering angrily: “You don’t have to destroy my car.” It was four in the morning on Saturday and Cairo was under curfew, but we had decided to risk the checkpoints rather than wait at the airport until dawn.

The youngest-looking man in the platoon methodically opened every zipper bag and wallet, sniffing my traveling companion’s shampoo and quizzically squeezing the earplugs that came in our Turkish Airlines complimentary traveler’s kit. This turned out to be only the second most invasive search of the night. Triumphantly, he pulled out our books.

Michael had The Girl Who Played With Fire and Eugene Rogan’s The Arabs. Foolishly, I had a brought a copy for friends of my book about Hezbollah, A Privilege to Die.

“What’s this book about?” a military intelligence officer asked me. That’s when he recognized me as the author from the jacket photo. Without a word, he ran to deliver the damning evidence to an even higher officer.

We waited for half an hour, shivering. The soldiers eyed me coldly. None of the usual smiles and chatter I’m accustomed to in Egypt.

A colonel pulled my friend aside.

“You want to know why these soldiers are so jumpy?” he said. “State television has been showing people that look just like your friend there, blaming them for the protests and violence.”

Egyptians have a well-earned reputation for hospitality, which has been a boon to the country’s bread-and-butter tourist trade. Many people seem to enjoy foreigners, normally.

There’s another strand of history that can be summoned though: that of inducing xenophobia in times of crisis. My Greek forebears did it time and again in the turbulent and pogrom-scarred years during which they forged a nationalistic identity after independence in 1821. Egypt has experienced its own periodic bouts of ethnic cleansing since 1919, and a spell of anti-foreigner rioting in the 1950s drove out most of Egypt’s historic Greek community.

This past week’s hysteria about foreigners – engineered by state television and by disingenuous statements from Egyptian leaders laying responsibility for popular unrest on foreign agents – taps into a deep strain of anxiety among Egyptians about their future.

It’s easier to blame foreigners than to confront internal divisions, and today’s rhetoric in Egypt has cast blame far and wide, but, playing on regional political realities, especially on Israelis, Americans, Qataris and Iranians.

In the pre-dawn chill on Saturday, I felt more foreign than I’ve felt at any point in my last eight years reporting in the Arab world. The friendly colonel at the military intelligence checkpoint hadn’t fallen prey to the idea, but his soldiers had.

Our books were returned and we were dispatched into the night.

The most invasive search came an hour later, and just a few hundred meters from our final destination in downtown Cairo. A wild-eyed plainclothes intelligence officer blanched when he saw my Greek passport. “A foreigner? Here? Now?” he screeched. “There is no possible good reason for you to be here.”

He dragged our bags into the storefront commandeered by a sleeping platoon of soldiers. “They have laptops!” he shouted. “Computers! Headphones! Cables!” He flung them every which way across the floor, and woke his bewildered commanding officer, who silently checked our equipment and papers, and cleared us to proceed.

“We must be careful,” he said. “The other day, you know what I found? A Turk with a flash drive. A flash drive! A single flash drive could destroy this entire nation.”

Released from his paranoid late-night fantasy, we finally went home, victims only of a passing, crazy moment. Let’s hope that for Egypt, this state-induced frenzy doesn’t last much longer.