How a handshake in Helsinki helped end the Cold War

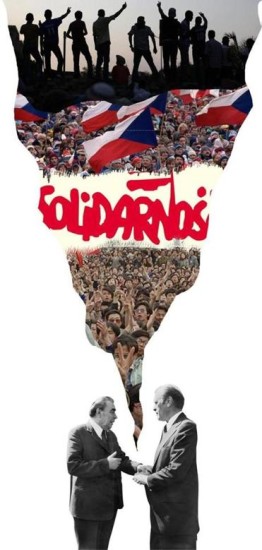

AP AND GETTY IMAGES PHOTOS; GLOBE STAFF PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and President Gerald Ford met in Helsinki at the All European Conference on Security and Cooperation in July 1975.

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

EIGHT HUNDRED YEARS AGO this summer, King John and a group of feudal barons gathered at Runnymede on the banks of the Thames River. There he agreed to the Magna Carta, which for the first time limited the absolute power of the monarch and established a contract between ruler and ruled. The mother of modern treaties and law, the Magna Carta began a global conversation about the responsibility of the powerful toward people under their control.

A scant four decades ago, also this summer, another gathering in the Finnish capital of Helsinki produced a second series of accords. While far less well known, the signing of the Helsinki Accords was a critical juncture in the long struggle of the individual against state authority. Building on some of the same ideas that undergirded the Magna Carta, the Helsinki Accords codified a broad set of individual liberties, human rights, and state responsibilities, which remain strikingly relevant today, whether the subject is China’s Internet policy, the Islamic State’s latest outrage, or the American “war on terror.” The language of human rights has become the lingua franca for criticizing misbehavior by states or quasi-governments.

Today, most governments have signed on to the United Nations’ definition of universal human rights, only disagreeing about whether their own transgressions run afoul of them. Rights groups are ubiquitous, criticizing the treatment of American prisoners, Chinese sweatshop workers, Iranian dissidents, and other groups whose rights are abridged.

Yet for the widespread agreement that human rights represent shared, universal values, it’s still hard to predict when a campaign based on moral accusation can change the actions of a state. Indeed, the question is no longer whether human rights can make a difference, it’s whether they will in any particular case.

It wasn’t always so. Until recently, human rights were hardly part of the realpolitik discourse and were certainly not considered an effective cudgel against powerful regimes. That changed 40 years ago, when powers from both sides of the Iron Curtain signed the Helsinki Final Act and unwittingly ushered in the era of the human rights group.

Solidarity in Poland, Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, and the Moscow Helsinki Group played key roles in the fall of the Soviet Union. They galvanized public dissatisfaction at home, embarrassed their governments abroad, and catalyzed the Soviet bloc’s loss of legitimacy. Many historians now believe that the 1975 Helsinki Accords and the human rights movement they engendered played a pivotal role in ending the Cold War, far exceeding the humble expectations of the diplomats who brokered the agreement.

“The most important legacy of the Helsinki Final Act today is that citizens have the right to monitor and report on the human rights records in their own country,” said Sarah Snyder, a historian at American University who has written a book called “Human Rights Activism and the End of the Cold War.” Prior to 1975, groups like Amnesty International tried to create international pressure with letter-writing campaigns, usually from outside the country where an injustice was occurring. Snyder believes that Helsinki created a new paradigm of human rights and a global slate of organizations that pursued them, with lasting impact — all the more impressive, Snyder said, because Helsinki wasn’t a legally binding treaty. “The only way it was binding was morally,” she said.

Academics have given a name to the idea that human rights advocacy can change facts on the ground: “The Helsinki Effect,” also the title of a 2001 book by political scientist Daniel Thomas, which popularized the argument that human rights trumped geopolitics and economics in resolving the Cold War.

How did a nonbinding, lumbering bureaucratic agreement reached four decades ago spawn the modern human rights movement? And what’s left of the legacy of Helsinki?

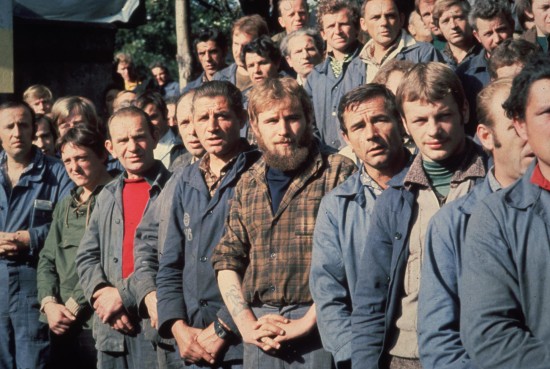

KEYSTONE/GETTY IMAGES

Members of the Polish trade union, Solidarity, on strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in August 1980.

AT THE HEIGHT of the Cold War, the Soviet bloc was a closed and inaccessible society. Many people who lived behind the Iron Curtain weren’t allowed to leave, and outsiders were permitted only tightly controlled, limited glimpses at life inside. The specter of cataclysmic conflict hung over East and West, with both sides brandishing thermonuclear and conventional arsenals that were unthinkably vast and destructive.

Throughout the Cold War, there were points of tension followed by periods of accommodation. The Helsinki Accords marked one of the latter. Relations across Europe had become so strained and so dangerous that Moscow, Washington, and all the capitals in between agreed there had to be some degree of relaxation. Both sides wanted to avoid a continental war between the superpowers. Both sides sought to end what they saw as belligerent expansion by the other.

They gathered in Helsinki on Aug. 1, 1975, to sign an agreement that turned out to be a seminal breakthrough — although not in the way that either side expected. The agreement signed by 35 states, including the United States and the USSR, focused for the most part on reestablishing respect for borders, national sovereignty, and peaceful resolution for future disputes between states. It also included a clause recognizing universal human rights, including freedoms of thought, conscience, and belief.

President Gerald Ford was castigated by his domestic critics for signing away the farm, because he had acknowledged Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. Meanwhile, the Soviets trumpeted Helsinki as a tremendous victory, enshrining their sphere of influence and providing international legitimacy to their repression of citizens and governments in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and elsewhere. They were so unconcerned about the human rights provisions that they published the Helsinki Final Act in full in the pages of the state newspaper, Pravda.

Western diplomats had modest hopes that the personal freedoms enumerated at Helsinki would ease the way for Eastern Bloc spouses married to Westerners, and for cultural and academic exchanges that promoted international dialogue.

But the importance of Principle Seven became evident almost before the ink was dry. Civic groups sprung up across the Eastern Bloc, determined to exercise their right to monitor their own governments’ compliance with Helsinki. Andrei Sakharov, the famous Soviet dissident, oversaw the founding of the Moscow Helsinki Group at his apartment in 1976. Activist playwright Vaclav Havel helped set up Charter 77 in Prague the following year. A Helsinki watch group opened in Poland in 1979.

The watch groups became very public thorns in the side of Communist governments. Their leaders were well known domestically and had contacts in the West, particularly in the press. They mobilized global attention to the human rights abuses of the Soviet Union and its client dictators.

And when governments subjected the watch groups to withering pressure, the activists asked their supporters outside the Iron Curtain to establish a unified organization that could defend the Helsinki Watch monitors. Human Rights Watch, perhaps the best-known and farthest-reaching global rights advocacy group today, originated with the Helsinki Watch group founded in 1978.

A brilliant, if perhaps unintended, enforcement system was built into Helsinki. All the signatory nations agreed to reconvene regularly, and the 10-point document contained many items of great political and security import to the Soviet Union. If the Soviets wanted to keep the benefits of Helsinki, they’d have to put up with attacks on their human rights record at the follow-up meetings.

“Without this follow-up mechanism, I think there would have been a big celebration after the signing, and we never would have heard of the Helsinki Final Agreement again,” Snyder said.

Instead, a panoply of Eastern Bloc activists and their Western supporters flooded diplomatic confabs at Belgrade, Madrid, and Vienna with details about oppression and abuses. Often, the Helsinki monitors became celebrities themselves, drawing widespread attention when they were persecuted and detained by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies.

The Helsinki-inspired human rights movements put a face on government oppression and placed rights atop the Cold War agenda alongside arms control. To the frustration of Soviet leaders, the world became absorbed by the plight of jailed activists and refuseniks denied exit visas.

By time Mikhail Gorbachev took over the leadership of the Soviet Union in 1985, he couldn’t sidestep human rights concerns when he began to negotiate a full détente.

THE NAMING AND SHAMING techniques pioneered by the Helsinki monitors run deep in the DNA of contemporary human rights groups. “The mechanisms that were so essential to Helsinki remain a key tool of the human rights movement today,” said Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch. “How does the human rights movement get anything done? By shaming, and by enlisting powerful governments to act on behalf of victims of human rights violations.”

For decades after the ratification of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, human rights remained largely an abstract concept in world politics. Most governments agreed with the principle but comfortably ignored human rights in practice.

The crumbling of the Soviet empire gave the human rights movement both experience and legitimacy. The Berlin Wall came down, and Eastern Bloc countries toppled their homegrown dictators. Lech Walesa, head of the Solidarity trade union, was elected president of Poland. Vaclav Havel, a playwright and signatory of Charter 77, won the presidency of Czechoslovakia and worldwide renown as a highly cultured philosopher-king. A generation after the Helsinki monitors came to prominence as victims of tyranny, they had become the face of a new democratic political elite.

The changing values that elevated them have become part of the world’s political orthodoxy; even governments that routinely violate human rights still pay them lip service.

“Even North Korea is pretending to accept human rights,” Roth said. “Governments care about their reputation and don’t want to be seen as violating human rights norms.”

Authoritarian backlash is another legacy of the Helsinki era. Dictators have also studied the rise of the civic monitors, and concluded that groups like Human Rights Watch really could cause them problems. A common result has been to strike hard and quickly against human rights groups, especially when they are run by locals who have moral authority. Vladimir Putin’s rise to power has been accompanied by the silencing and killing of many credible rights monitors. Iran’s ayatollahs deployed maximal force to destroy the “Green Revolution” of 2009. Egypt’s dictatorship rails against any criticism of its human rights record as meddling and foreign interference, and prosecutes domestic rights group with the same zeal that it pursues armed antigovernment insurgents. Despotic regimes have made it common practice to starve rights groups of funding and deny them permits to operate.

Given the success of authoritarian regimes, not everyone is convinced that the Helsinki effect is as pronounced as its champions claim. Among the many commemorations scheduled for the 40th anniversary year, a group of scholars is gathering at the Sorbonne in Paris this December to explore how much the agreement and the human rights movements it created really were responsible for social and political change.

“My feeling is that we really don’t know that much, beyond generalities, that is, in terms of how the ‘Helsinki effect’ effectively operated by way of changing East European societies from within,” one of the organizers, Frédéric Bozo, a historian the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, wrote in an e-mail. He’s also not sure whether anything about the Helsinki era applies to today’s thorny nexus of human rights and political power — another area he said is ripe for further inquiry.

Skeptics of the narrative of human rights triumphalism point out that the US government always paid more attention to transgressions committed by its rivals than by its friends. That pattern continues today in Washington, with pointed human rights criticism of China, Russia, Cuba, and Iran. There’s far less enthusiasm in the West for documenting human rights abuses by allies like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel — or for that matter, addressing the plight of those held without trial at Guantanamo Bay or killed in drone strikes.

In some ways, the world was more binary during the Helsinki era. Two major superpowers dominated the world; if they agreed, most other nations fell into place. Nonstate actors hadn’t assumed their central role in international politics, with their destabilizing penchant for asymmetric warfare.

Even pessimists like Anne-Marie Le Gloannec, a political scientist at Sciences Po in Paris, admit that Helsinki produced an enduring change. Le Gloannec believes the world is headed for dark times, with resentment driving an anti-Western wave led by tyrannical demagogues like Russia’s Putin. The war in Ukraine could spread farther into Europe, she believes, and human rights norms won’t do anything to calm tensions.

Despite her grim forecast, Le Gloannec belives that civic and human rights are here to stay — thanks to Helsinki. “We have a new paradigm,” she said. “People have the right to defend their rights, to fight for their rights.” However fragile, it’s a paradigm that for the first time placed individuals, rather than nation states, at the center of international relations.

Bahrain’s unfolding crackdown

Since the middle of Ramadan, when I wrote about Bahrain’s sweep of Shia activists, the government has announced charges against 23 alleged coup plotters, saying they were planning to overthrow the government with funding from abroad, mainly Iran.

Since the middle of Ramadan, when I wrote about Bahrain’s sweep of Shia activists, the government has announced charges against 23 alleged coup plotters, saying they were planning to overthrow the government with funding from abroad, mainly Iran.

Bahraini human rights activists continue to protest the government’s detention of hundreds of Shia politicians and activists; on Sept. 11 they began a “sit-in,” pictured here, demanding an end to torture and the release of all those detainees not charged with a crime.

King Khalifa gave an angry speech, saying the years of tolerance and pardons were over, while the government belatedly started making a case to public opinion beyond the Gulf, addressing the allegations of torture and illegal detention while also articulating claims that the Shia political opposition figures it arrested pose an actual threat to the state.

Bahrain’s Ambassador to the U.S., Houda Ezra Ebrahim Nonoo, wrote in her letter to the Times:

Against the backdrop of continuing incidences of violence and public disorder, arrests were made because significant evidence was discovered of a network planning and instigating attacks on public property and inciting violence. … Our commitment to further reform within an open, tolerant Middle East society remains undiminished.

Solid evidence could help that case, but so far the Bahrain case highlights some really interesting regional questions.

- Can the ruling families in the heterogenous Gulf countries find a way to extend minority rights while maintaining stability?

- Are the Shia minorities in Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia seriously interested in taking power, like the Shia in Iraq, or will they be satisfied with a more fair political system?

- Is Iran actively stirring up the Shia in the Gulf countries as a threat to ruling families, or are we seeing nothing more than flow of alms money from religious Shia through their references – usually based in Iran and Iraq – back to the faithful in the Gulf?

- How much rule of law is possible in states were absolute authority is concentrated in the hands of a single, hereditary ruling family?

- What is the Khalifa family trying to accomplish long-term? And what prompted the timing of this wave of arrests: Real information about a prospective coup? Concerns that Shia parties would win a majority in the October parliamentary elections? Real worry that simmering unrest would hurt Bahrain’s ability to win and retain foreign companies?

The Bahraini press has begun to publish some of the government’s answers to these questions. There have been some newspaper columns in the Gulf that express the ruling families’ fear of Iran-backed Shia uprisings, an anxiety that has percolated throughout the peninsula in various forms for centuries.

Steven Sotloff wrote an excellent piece on The Middle East Channel about Bahrain’s Shia crackdown, in which he details a lot of the background in what he describes as conflict not between Shia and Sunni but between the Shia majority and the ruling Khalifa family. Sotloff gives us a lot of useful detail about the government’s housing policy, which favors newly naturalized Sunni immigrants recruited for the security forces over long-time Shia citizens, and other Shia grievances about employment and political rights. His measured tone helps referee a lot of the heated claims about Iranian funding, dual loyalty and sedition.