Iran vs. Saudi: Two repressive blocs face off

Photo Credit: Mohammed Huwais / Stringer

[Published in Foreign Policy.]

By Thanassis Cambanis

BEIRUT — The war in Yemen and the breakthrough nuclear agreement between Iran and the United States have sent the already frenzied Middle East analysis machine into meltdown mode. These developments come fast on the heels of almost too many changes to keep track of: the Iraqi government’s capture of the city of Tikrit, rebel gains in northern and southern Syria, and mass-casualty terrorist attacks in Tunis and Sanaa.

This drumbeat of headlines, however, should not distract us from the larger meaning of events in the Middle East. We are witnessing a struggle for regional dominance between two loose and shifting coalitions — one roughly grouped around Saudi Arabia and one around Iran. Despite the sectarian hue of the coalitions, Sunni-Shiite enmity is not the best explanation for today’s regional war. This is a naked struggle for power: Neither of these coalitions has fixed membership or a monolithic ideology, and neither has any commitment whatsoever to the bedrock issues that would promote good governance in the region.

This is, in some ways, an updated version of the vast and bloody struggle for hegemony that shook the Arab world in the 1950s and 1960s. In that era, a coalition of reactionary monarchs, led by Saudi Arabia, did battle with a coalition of Arab nationalist military dictators, led by Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser. Just like in that past era, every single major player today is opposed to genuine reform and popular sovereignty.

Today’s ascendant regimes are all reactionary survivors — and sworn enemies — of the Arab Spring. The Iranians mercilessly crushed the Green Revolution in 2009, and have invested heavily in authoritarian partners in Iraq and Syria, paramilitary group such as Hezbollah, and non-democratic movements in Bahrain and Yemen. Iran’s leaders are theocrats, but they are savvy and pragmatic geopolitical worker bees: They have backed Sunni Islamists and Christians, while even some of their close Shiite partners — like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, an Alawite, and the Zaidi Houthis in Yemen — belong to heterodox sects and don’t share their views on religious rule.

On the other side of the struggle are the Arab monarchs from the Gulf, run by the same families that brought us the Yemeni war of the 1960s. They have extended their writ through generous payoffs and occasional violence, like the Saudi-led invasion of Bahrain in 2011, which saved the minority Sunni royal family from being overrun by the island kingdom’s disenfranchised Shiite majority.

This Saudi-led alliance is Sunni-flavored, but it would be incorrect to see it as monolithically sectarian.

This Saudi-led alliance is Sunni-flavored, but it would be incorrect to see it as monolithically sectarian. Not long ago, in fact, Saudi Arabia underwrote the same Zaydis it is now bombing in Yemen. The current coalition relies for populist credibility on Egypt, whose governing class is dominated by secular, anti-Islamist military officers. It enjoys dalliances in various conflict theaters like Syria and the Palestinian territories with Muslim Brothers and jihadis. It has drawn extensively on help from the United States — and on occasion from its supposedly sworn enemy, Israel.

Perhaps the best glimpse of the Saudi-led alliance’s goals came when Kuwaiti emir Sabah al-Sabah addressed the Arab League at the end of March, in the meeting that inaugurated the war in Yemen.

“A four-year phase of chaos and instability, which some called the Arab Spring, shook our region’s security and eroded our stability,” the emir thundered. The uprisings, he said, encouraged “delusional thinking” about reshaping the region — perhaps a reference to Iran’s ambitions of regional influence, perhaps a reference to the ambitions of Arab reformers to limit the influence of the repressive states propped up by the Gulf monarchies. To the emir, the only outcome of uprisings was “a sharp setback in growth and noticeable delay in our progress and development.”

This is the crux of the regional fight underway: the old order, or a new one that would transform the balance of power — while changing little else about the way the Middle East is governed. The Saudi bloc wants to turn back the clock to the status quo ante that existed before the uprisings. The Iranian bloc wants to permanently alter the region’s balance of power. Both factions are run by opaque, secretive, repressive, and violent leaders. Neither side is interested in popular accountability, better governance, or the rights of citizens.

For all the doubts about Saudi Arabia’s capacity to craft and execute complex policy, the kingdom has cobbled together a formidable coalition. It quickly signed up most of its clients and partners for the air campaign, including Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Sudan, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates. The United States supported the war, despite its reservations. Of the kingdom’s close allies, only Pakistan has so far resisted pressure to join the fight.

In just the last year, we’ve seen at least two major volte-face. Riyadh helped engineer a regime change in Egypt, ushering President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power. After experimenting with quasi-democracy and a Muslim Brotherhood presidency that defied the powerful Gulf monarchies, Cairo is now governed by a military dictator who walks firmly in lockstep with Riyadh — even promising to dispatch ground troops to a war in Yemen of which he would have probably preferred to steer clear. Qatar, the unbelievably rich emirate that has long cultivated an independent foreign policy, also found itself strong-armed by Saudi Arabia and finally caved. Its emir abdicated in favor of his son, a 34-year-old political novice, and today Doha is reading from Saudi Arabia’s song sheet.

Both examples show that this is not a monolithic bloc bound by uniform ideas of authoritarian rule or Sunni supremacy. Instead, it is a messy realpolitik coalition hammered together by shared interests — and at times by bribes and blackmail. Its members don’t agree on everything: Saudi Arabia hates Russia, in part because Moscow backs Iran and Syria. Egypt loves Saudi Arabia because Riyadh keeps its economy afloat — but it also loves Russia, because it can play off military aid from Vladimir Putin against that from the United States. In public, Sisi praises the Gulf leaders — but in leaked private recordings, he dismisses them as oil bumpkins who can be bilked of their money by more dynamic Arab nations. Qatar no longer openly defies Saudi Arabia, but it still supports Muslim Brothers and jihadis in Syria to the extent it can, and in opposition to Saudi preferences.

Since Saudi Arabia’s gloves came off in Yemen,

Sunnis across the region have expressed a kind of fatalistic relief: At last someone is doing something to confront Iranian influence.

Sunnis across the region have expressed a kind of fatalistic relief: At last someone is doing something to confront Iranian influence. But Tehran has extended its influence carefully, hedging its bets by supporting multiple groups in every conflict zone and always maintaining a degree of remove — if their investments fail, it will have not lost a war in which it was a declared combatant. This blueprint has served Iran well during 30-plus years of intervention in Lebanon and Iraq, and four years of orchestrating major combat in Syria. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has entered the Yemen war directly, and therefore has no cover. It will own the civilian casualties, and inevitably — when the war has no clear and easy outcome — it will own a failure.

History is not on Riyadh’s side in this campaign. Regional wars tend not to go well for invaders; just think of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait or the last Yemen war in the 1960s. The U.S. invasion of Iraq should also offer a cautionary lesson: Many people at the time, including some Iraqis, felt that some major action was better than the status quo, that toppling Saddam Hussein would at the least get a hairy situation unstuck. They were soon disabused of that notion, as Iraq spiraled into chaos.

America should take particular care in this conflict. It has built deep alliances with Saudi Arabia, and it has been far too hesitant to reinvent its dysfunctional relationship with Egypt in the post-Mubarak era. It should act as a brake on Saudi Arabia’s outsized expectations in Yemen, and it should exact a price for any support it gives the war there. Any campaign in Yemen should strengthen, rather than undermine, counterterrorism efforts there, and the United States should share its military know-how in exchange for Saudi cooperation on the Iran deal.

Sure, it’s bizarre to see the U.S. military working with Iran to battle the Islamic State in Iraq, while working against Tehran in Yemen. It’s also refreshing. This isn’t a homily; it’s foreign policy. It’s encouraging to see the United States operating around the edges of a complex, multiparty conflict and finding ways to advance American interests. Its next challenge will be finding new ways to simultaneously pressure rivals like Iran and recalcitrant allies like Saudi Arabia.

But to a large extent, the United States is a sideshow: The main event is the regional struggle for influence between the Iran and Saudi blocs. One need only look at the two major events this spring — the Iran nuclear deal and the capture of Tikrit with the help of Tehran’s military advisors — to get a sense of who’s winning. America’s preferred side has bumbled impulsively from crisis to crisis, buying or strong-arming support and launching military adventures that are likely to produce inconclusive results. Iran’s side, meanwhile, has crafted tight state-to-state relations with Syria and its onetime enemy Iraq, and has deepened its influence in Afghanistan, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Yemen. Despite the theocratic dogma of Iran’s Shiite ayatollahs, the regime in Tehran has managed to position itself as the regional champion of pluralism and minorities, against a Saudi grouping whose philosophy has drifted dangerously close to the nihilism of al Qaeda and the Islamic State.

Unless Saudi Arabia and its allies can learn a new, more durable style of power projection, their costly feints will only buy short-term gains. The kingdom might manage to bomb the Houthis back to their corner of Yemen, and its Syrian clients may seize some more towns and cities from Assad, but the long-term trend points in Iran’s favor.

Regional realignment with Hezbollah, Assad & Iran?

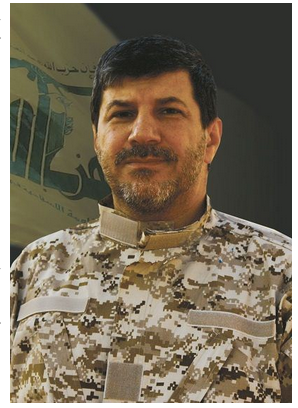

Hassan Laqqis, assassination scene. Source: Al Manar

There’s been lots of talk about the regional consequences of the Iran nuclear deal, and of a realignment as the West realizes that it might prefer Assad in power to a jihadi-dominated rebel government or some version of the current punishing settlement. Ryan Crocker told The New York Times that the US should resume cooperating with Damascus against Salafi jihadis, and various analysts and diplomats have been speculating that Iran, Assad, Hezbollah, and the US share plenty of common interests. Saudi Arabia and Israel stand to lose if the US begins to behave like a mature superpower, collaborating where it sees fit rather than holding itself hostage to the agenda of small allies behave as peers rather than clients.

The latest trigger was yesterday’s assassination of a Hezbollah official in Beirut. (Hassan Lakkis, according to Hezbollah’s Al-Manar Television, played an important role in the fight against Israel; Reuters reports that Lakkis was fighting recently in Syria.) That killing once again raised the question of Hezbollah’s broader direction. Has it provoked a maelstrom of jihadi attacks, retaliation for Hezbollah’s role in the Syrian civil war? Or is the conflict in Syria playing out in the interests of Hezbollah, Assad and Iran?

I think there’s some evidence that three years after a non-violent popular revolt against Assad’s nasty dictatorship, Assad has finally managed the shape the conflict he wanted. He wiped out the non-violent resistance, the intellectuals and the pluralists, and continues to mass his firepower against the FSA rather than the jihadists. As a result, the conflict pits an authoritarian but non-sectarian dictatorship against a Sunni rebellion dominated by takfiri jihadists. Hezbollah entered the war supposedly to fight the sectarian jihadis over there before they made it over here, a la George W Bush. It sounded facile then, but now it sounds true; each time there’s a bomb of assassination in Lebanon, it adds credence to Hezbollah’s claim that it’s on the side of a Middle Eastern order that tolerates multiple faiths and power-sharing, while on the other side Saudi and other Gulf money is supporting extremists who want to recreate the 7th Century Caliphate. Self-serving, but perhaps, true.

We’ve seen hints of change:

- An increase tempo of back-and-forth attacks in Lebanon.

- Stronger desire by Lebanese national institutions to contain the crisis.

- Reports that the US has shared intelligence with Lebanon in order to protect Hezbollah from attacks.

- A real push – in Track 2 and perhaps Track 1 diplomacy – to make the January talks in Geneva really amount to a negotiation for a settlement in Syria.

- The Iranian nuclear deal, which could calm anxieties about the regional Iran-Saudi cold/hot war, and allow for some tit-for-tat that could reduce global interest in the Syrian theater.

What should we look for as signals of a coming, substantive change?

- Rhetoric from Hassan Nasrallah that opens the door to a frigid détente with the US on some issues.

- Continuing restraint by Hezbollah in its response to attacks and assassinations.

- Agreements or accords that result from the vigorous outreach by Iran’s foreign minister to the leaders of the Arab countries in the Gulf.

- Offers, even totally rhetorical ones, from Assad to cooperate with the US against the jihadi groups in Syria.

The interim Iranian nuclear agreement could easily collapse (Marc Lynch writes here about the enormous potential but also the need to remember that it could all come to naught), but it’s a major opening. Iran has always been a more natural geopolitical ally for the US than the tiny oil-rich monarchies of the Arabian peninsula. It’s hard to imagine a full realignment without an internal shift in the governance of Iran, but perhaps, that could occur with a political shift short of regime change. The most likely outcome is incremental, with Iran and the US finding more avenues of cooperation but stopping short of an open embrace. But even the prospect of a cooling in the US relationship with absolute monarchs of the Gulf and the hawkish establishment of Israel, in favor of a more pragmatic policy that leaves room to cooperate with all the region’s heavyweights, has prompted a panic in Riyadh and Israel. That anxiety suggests it’s a very real prospect, and one that in the long-term would serve to cool down the region.