We are the war on terror, and the war on terror is us

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

THE FIRST signs of America’s transformation after 9/11 were obvious: mass deportations, foreign invasions, legalizing torture, indefinite detention, and the suspension of the laws of war for terror suspects. Some of the grosser violations of democratic norms we only learned about later, like the web of government surveillance. Optimists offered comforting analogies to past periods of threat and overreaction, in which after a few years and mistakes, balance was restored.

But more than 15 years later — nearly a generation — we have not changed back. Shocking policies abroad, like torture at Abu Ghraib and extrajudicial detention at Guantanamo Bay, today are reflected in policies at home, like for-profit prisons, roundups of immigrant children, and SWAT teams that rove through communities with Humvees and body armor. The global war on terror created an obsession with threats and fear — an obsession that has become so routine and institutionalized that it is the new normal.

The perpetual war footing has led to a militarization of policy problems under the Trump administration. The share of recently active-duty military officers in senior policy positions exceeds the era after World War II, historians say. Border police chase people down outside homeless shelters and clinics, deport legitimate visitors, and swagger around airplane jetways demanding identification. And another burst of defense spending is just around the corner.

All of this is a sign that the United States has fallen into a trap familiar to many former colonial powers: They brought home their foreign wars at great cost to their democracies. Colonial Great Britain normalized inhumane treatment of civilians abroad in service of empire, and then meted out the same Dickensian abuse to the poor at home. In its futile effort to hold onto its colony in Algeria, France rallied anti-Islamic sentiment and pioneered indiscriminate counterinsurgency; as a result, to this day in France, religious freedom and suspects’ legal rights still suffer. Liberals in Israel argue that the practices necessary to perpetuate the occupation of Palestinian territory have fatally eroded the rule of law.

Indeed, the longer a conflict endures, the more deeply all parties to it are corrupted; citizens asked to misbehave on behalf of their country find they can’t stop when they return home or go off duty.

For more than a decade and a half, America has embraced a vast military campaign that relied on major shifts in US values and policies. A covert assassination program targets terror suspects with no judicial process. Many bedrock civil liberties have been traded away. Some initial excesses, like the use of torture, were curbed. But the norm is still inhumane forms of detention, and abuse that meets the definition of torture. Meanwhile, the United States has maintained what is for all intents and purposes an extrajudicial gulag in Guantanamo Bay since 2001.

Collectively, all these data points have struck with the force of a meteor against America’s culture of due process and institutional checks and balances.

As this new mindset took root, even some of its architects took notice — and were alarmed. Midway through Obama’s presidency, a White House adviser confided concerns about the executive branch’s “kill list” and accelerating use of drone strikes. “One day historians are going to excoriate us for the kill list, and they’re going to ask why no one questioned what we’re doing,” this adviser said.

We’re still waiting for that day. In the meantime, we must understand the full extent of the damage. America became its war on terror, abandoned its principles to visit horrific violence abroad, and then brought into domestic politics an ease with lawlessness, caprice, imperial-style occupation. A global war, by definition, must also be waged at home.

A sizable contingent today believes that the military solution is the only and best one for many problems, from terrorism to corruption to managing diplomatic relations. And while knee-jerk militarism is poisonous for a republic, we would do well to remember the failures of civilian politics that make even generals of dubious repute like David Petraeus seem like potential saviors.

“We’re pell-mell down a road that we don’t even we realize we’re on anymore because we’ve got so used to the military option,” said Gordon Adams, a professor emeritus at American University and co-editor of the book “Mission Creep: The Militarization of US Foreign Policy?”

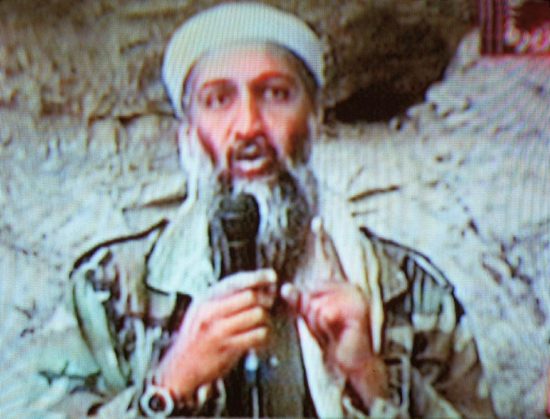

It’s not that military officers are bad or necessarily wrong — it’s that they offer just one perspective on policy problems, and they’ve been trained to consider one tool: force. That’s well and good when military officers are in a room with other experts with other perspectives, debating how best to deal with Osama bin Laden. It makes less sense when military officers, active-duty and retired, are the only people in the room debating US policy toward Russia, China, the Middle East, or issues even further from their lane, like airport security and international trade. It becomes absurd when doctrines that failed so spectacularly in Iraq and Afghanistan somehow worm their way into local police departments in the United States.

Immediately after the attacks of 9/11, America’s political class decided its only goal was stopping future terror strikes. Legislators forsook legislative oversight. Courts were reluctant to limit metastasizing executive power. Rights were stripped by laws like the USA Patriot Act, which watered down protections against overzealous law enforcement hard won over a century. It’s not hard today to draw a line from the bullying jingoism of 2001, when opposing the Patriot Act reeked of disloyalty or treason, to the election of President Trump, and his reckless “America First” positions that jeopardize global security in 2017.

A bipartisan consensus views remote strikes against suspected terrorists as an efficient refinement on the early, labor-intensive, versions of counterterrorism. Although the rest of the world still musters outrage when civilians are killed, the issue has all but vanished domestically. There is simply no domestic political cost for accidentally bombing a hospital in Afghanistan, or killing 10 children in Yemen, or the deaths of dozens of civilians in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere. Think about the shock that the My Lai massacre caused to American politics less than half a century ago. Now consider the cultural shift whereby the public accepts and ignores routine massacres — usually committed with air power, and sometimes with a plausible claim that accidents were honest mistakes or not directly America’s fault or the victims were sympathetic to American enemies, if not actually guilty of anything.

This is a sea change. In the 1970s, when the Church Commission revealed that the CIA, sometimes with presidential support, had assassinated foreign leaders, it was a scandal. The uproar curbed the powers of the CIA for decades.

Compare that to the last 16 years; black ops are fetishized and widely supported. There are no checks and balances. The president can — and has — decided to assassinate terror suspects, including American citizens. Hardly anyone raises a peep except for the ACLU and a handful of other minor constituencies with a hard-line commitment to civil liberties. That’s how strange, and troubled, is our adoption of a heedless counterterror gospel. Obama seemed to order assassinations with such care and deliberation that criticism only came from the fringe; Trump critics will find it difficult now to object to a kill list on grounds not of principle but of personnel.

Afghan war veteran Brendan O’Byrne articulated this disturbing transformation in an essay this month in the Cape Cod Times. He likened the endless quest to kill terrorists to cycles of violent abuse inside families. As a troubled youth, he recalled, he attacked his father, who then shot O’Byrne in self-defense. “America is like my father, creating the very thing it has to kill before it kills them,” O’Byrne writes. “Where is our responsibility for creating the terrorists we are now fighting?”

America has confused self-defense with an impulse to kill “every possible threat,” O’Byrne continues: “We run the risk of becoming the very thing we claim to be fighting against — terrorism.”

Our wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have stretched on so long they’ve become the fixed backdrop to a country at war against terror in more places than the average American can track. The Pentagon now operates in roughly 100 countries worldwide. To be American is to be at war.

“I’m teaching college students this semester — they can barely remember a time when these wars were not underway,” said Jon Finer, a former war correspondent in Iraq who later became chief of staff to then-secretary of state John Kerry. “Combat has become a normal, regular feature of American life.” Over a decade Finer switched careers, from journalist to senior national security official, only to find the American military still engaged in counterinsurgency with jihadis in the same provincial deserts of northern Iraq.

The war against terrorism aspired to reduce to zero the number of attacks on American territory — no matter how many attacks that would require America to conduct, and provoke, abroad.

A society that embraces war without end eventually stops recognizing that its initial adrenaline response is abnormal. Fear becomes the baseline. The mirage of zero-risk and the cult of war we embraced to find it have systematically warped our politics and society.

The extremes that led to Trump’s election — xenophobia, race-baiting, fear, disregard for rights — were nurtured by the many Americans mobilized to execute US foreign policy in the post-9/11 war zones. Military personnel, diplomats, aid workers, ideologues, apolitical contractors: Hundreds of thousands of Americans were steeped in war and brought that culture home. If you’ve learned one, brutal way to search cars at a checkpoint in Iraq, it’s hard to shift to the gentler methods when you’re working a few years later as an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent or police officer in middle America.

Trump’s America is our America, and it’s been taking shape for many long years. We won’t restore the balance and get the best of America back until we decide to end our war on terror and focus anew on the American rights that undergird our security even more than prisons and SWAT teams.

Trump’s Dangerous Attack on American Values

[Published at The Century Foundation.]

Why do so many people want to live in America? Why have so many, like my parents, emigrated to the United States, and why do so many prefer it over all other destinations? It’s not just because of America’s prosperous and diverse economy, or its promise of economic mobility and equality. It’s because America’s political, cultural, and religious freedoms have meant that people’s fates are less foreordained by last name, tribe, ethnicity, or religion than they are elsewhere. While imperfect, the American system has proven remarkably open to revision and improvement, trending over its history toward more openness and equality, and less discrimination and oppression. Individuals can choose their own course, and their own identity.

America’s story as an immigrant nation is neither all rosy nor simple. Racial and ethnic tensions have simmered along with every chapter of immigration, and for all the periods of openness, there have always been tragic moments when the gates were closed, including to many Jews during the Holocaust. And in many cases, America benefited economically and culturally from the arrival of refugees or immigrants created by America’s own foreign policy misadventures. My own parents came to the United States to study; one reason they stayed was because their home, Greece, was in the violent grasp of a military dictatorship that had been put in place with U.S. support. However, America also offered some Greeks like my parents a way out, and a new home. Such stories have been part of the American fabric since the beginning.

President Donald Trump’s executive order to close America’s borders to people from seven countries arbitrarily chosen as the most dangerous sources of terrorstrikes a body blow against a fundamental American conceit: that this country is a melting pot, and that we never discriminate on the basis of religion.

The anti-immigration measure unleashed over the weekend also attacked the fundamental notion of citizenship, by initially barring even permanent residents whose green card signifies they are in the last stage of the legal path toward citizenship (Trump was forced to walk back this element of the order). And it directly singled out Muslims as targets; whatever the verbal acrobatics Trump has engaged in since, his order and statements were clear; he wants to ban all Muslim immigration from these seven countries (and perhaps more later), while making special provisions to admit Christians from those same places.

Don’t Be Fooled: It’s a Muslim Ban

Of course, this is a Muslim ban, not a counter-terrorism measure. (Rudy Giuliani, a Trump adviser, confirmed as much talking to reporters.) It’s easy enough to see, if you’re open to fact-based policymaking, that a blanket ban on foreigners or members of some ethnic groups will do nothing to protect the United States from terrorist attacks, which in most cases have been perpetrated by attackers who were citizens, entered the country legally, or were members of groups not on the hot-button fear list of the day.

In standing against this shameful executive action, we certainly can and should make a case based on self interest. An immigration ban hurts America just as surely as it hurts many families and individuals. It hurts our economy, our workforce, our research and development prospects, our universities, and our vibrant tech sector. It will make our economy less competitive, our institutions weaker, and our companies less profitable. More broadly, it hurts us many times over as stewards and beneficiaries of an international order built on norms that if unevenly enforced were once quintessentially American in principle: equality, rights for all, opportunity, and colorblindness.

But most fundamentally, this outrage from the Trump White House harms us by damaging the foundation of American rule of law and equality, which are the very reasons this country has had such success and has grown into a worldwide beacon. Despite America’s checkered record, it remains a cherished home to that majority of its population descended from immigrants, and a choice destination for those seeking a freer life. There might be better places to live, but none, including the European nations with great social safety nets, offer an open society with equivalent individual rights and freedoms.

What we’ve witnessed over the last days has defied the already low expectations that Trump set in his first bellicose week in office. Unaccountable law enforcement officials denied lawyers and even members of Congress access to immigrants detained at airports. Unapologetic White House officials gloatedthat terrorists will be thwarted by an indiscriminate, punitive measure whose short-term harm is sure to be matched by its long-term ineffectiveness. While White House officials clarified parts of the order on TV and the president fanned the flames on Twitter, foreign governments began to take countermeasures and executive branch agencies appeared to trample on the separation of powers by ignoring court orders and legislative requests. Families separated by the order, and travelers whose visas and green cards were suddenly useless, scrambled to figure out when and if they could cross America’s threshold.

Under the current scheme it is likely that Trump will try to open America’s gates only, or primarily, to non-Muslims. I hope that such an effort will fall afoul of the letter of the American Constitution just as surely as it defiles its spirit. But as a longtime observer of the American political process and a student of some of its dark history, I fear that it will take uncomfortably long to reestablish a just order. Courts move slowly and deliberately. Even if they get it right on the first try, it might take years before a Supreme Court ruling strikes down a de facto Muslim ban. And maybe Donald Trump will find legalistic detours around justice, implementing his isolationist, racist, and xenophobic plan with just enough attention to detail that it squeaks through the judicial process. As George W. Bush’s torture policy showed, much can be accomplished that is against our laws and our values.

We are a stronger nation with our immigrants, those who assimilate as well as those who struggle. We are stronger for our establishment clause which separates not just church but synagogue, mosque and all other religious belief from our state. The day we make religion part of the litmus test for American belonging is the day we turn our backs on the most American idea of all: that America can always, in theory, be home to anyone who wants it badly enough. America today is neither a Christian nor chauvinist nation; it is a nation built on a communal belief, and its success is a testament to change, inclusion and secularism, to the power of a collective national ideal that accommodates all takers.

America Doesn’t Live in a Vacuum

Trump’s excesses are possible because of the abusive bloating of executive authority and security state powers. Rights-stripping, unfortunately, is also as American as apple pie, and many of George W. Bush’s escalations of federal power, fear-mongering, and immigrant abuse after 9/11 were built on erosions of rights contained in two signal pieces of legislation by Bill Clinton that were supposed to reform immigration and the legal process in death penalty and terrorism cases. As a journalist covering federal court in Boston after 9/11, I was aghast at the cavalier lack of concern among many law-abiding Americans for the legal rights of foreigners, terror suspects, and drug criminals. I was also surprised to learn how deep and bipartisan support ran for any action couched as anti-terrorism, even if its primary target was immigrants and nonviolent criminals, as demonstrated by Clinton’s “Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act” of 1996.

Obama walked back some of the worst crimes of the Bush era, ending torture, closing black sites, and rolling back some surveillance measures, but he enjoyed the perks of unfettered executive power. Guantanamo remained open, drone strikes accelerated, and America didn’t join Canada and Europe in shouldering the burden of today’s historic refugee crisis.

Now Trump has taken the tools assembled by his predecessors and is applying them to toxic ends.

What about other countries? Will they function as extras in a one-man play called “America First”? Doubtful. They will retaliate, and America will care; even Trump, probably, will care. Soon enough the world will react, and Trump and his sycophants will notice they don’t live in a vacuum. Unfortunately, like the valiant domestic protests, it will take quite a while for the response to curtain the abuse of power. But the response will be devastating. Iraq is imposing a reciprocal ban on Americans, which while mostly symbolic could undo that oh-so-important war against ISIS, whose frontline today runs through Mosul, where American and Iraqi troops are together pushing back a real terrorist threat.

And American allies, on whom America depends for so many economic and political benefits, might take umbrage at having their citizenship suddenly downgraded. Citizens of Canada, France, or the United Kingdom are suddenly demoted in the eyes of the United States to having lesser rights because of their origins—might not, in a reasonable world, the governments of Canada, France and the U.K. retaliate to make the point that all their citizens should be treated equally?

How we act in the world matters just as surely as how we act within our own borders. A parent who abuses strangers and cheats in the workplace can’t expect the same behavior to result in an ethical and peaceful home. Trump’s anti-immigrant policies won’t make us safer from terrorist attacks, nor will they solve any other American woes, real or imagined. But we shouldn’t only make the case against isolationism and chauvinism solely on efficacy. Because even if such policies worked, we should still oppose on principle all moves to close our borders, disavow American ideals, and discriminate against religious groups. We have no interest in prevailing as an authoritarian state.

Our Better Angels

Donald Trump and his team will have to moderate their contempt for political life and dissent. Even autocrats in weaker states find they have to manage and sometimes cave to public opinion. Even outright tyrants can’t ignore street protests or the discontent of vast swathes of the public. So too, Trump, even in his first climbdown on Sunday when he relented on green card holders, will learn that public support matters in political life, all the more so in a democracy, which America today most resolutely still is.

Since 9/11, Americans have struggled to find the right balance between our security and trespass against our freedoms, all too often accepting compromises on core values in a devil’s bargain to fight terrorism. In the end, our security comes from both our readiness and our values, our laws and our fundamentally democratic melting pot ideal.

For most of my life, I have tried to explain what makes America special to skeptical relatives, friends, and interlocutors from all over the world. Donald Trump’s immigration ban makes that job all the harder. But there is an answer, and it comes from the legions of Americans who instantaneously rose to fight the unjust measure. The Bill of Rights, the traditions of American citizenship, our institutions, and constitutional rule of law together pose formidable obstacles to a would-be tyrant. American history tells us that justice can prevail, even if it takes a long time. Let’s hope that we’ve learned our lessons from the last century, and that Donald Trump’s attempt to rewrite the American compact as a nativist, racist, and isolationist screed shatters before its first draft is finished.