Q & A with Micah Zenko

Micah Zenko’s “Ten What’s” for CFR’s Politics, Power, and Preventive Action blog.

1. What is the most interesting project you are currently working on?

Interesting to whom?

As an antidote to the mostly dismal political development in the Arab world these days, I have been trying to document some of the cultural responses to the ongoing turmoil in the region. I have been seeking out urban planners, architects, writers, filmmakers, and other people who are maintaining a creative life in the face of what can feel like a dead-end moment, politically speaking. In some cases I am writing profiles of people and their ventures, like a decaying abandoned mansion in Beirut that has been turned into a collective with an urban renewal mission. In other cases, I am exploring broader concern about the life and death of cities. The underlying question driving this effort is an inquiry into the capacity of public intellectuals to create tangible change.

2. What got you started in your career?

I always knew I wanted to be a writer. I just wasn’t sure what kind. When I was kid, I spent summers in Greece hearing stories from my grandparents about the war—for them, that meant World War II and the Greek Civil War that followed it and ended in 1949. I hatched a notion that I wanted to be a war correspondent without any real idea of what that meant, and somehow ended up following that calling. By the time I graduated from university and was working as a reporter, there were sadly plenty of wars underway. The utopian optimism that accompanied the fall of the Berlin Wall evaporated in Somalia, Rwanda, and the wars of Yugoslavian succession.

3. What person, book, or article has been most influential to your thinking?

It is so hard to pinpoint one single source, but if I have to limit it to just one, I would say it was The Plague by Albert Camus. I first read it as a teenager and I have read it again every five or so years since then. The characters fighting the plague while cut off from the rest of the world in Oran provide an ideal for how to try to keep a sense of purpose, and a moral compass, in trying circumstances. The heroes of the plague are not ideological. They are pragmatists, trying to be useful and to make sense of whatever comes their way, including human venality and the horror of the plague.

4. What kind of advice would you give to young people in your field?

Seek out mentors and editors who will invest time and energy in your work. Take seriously your craft and development as a thinker and writer, and keep your grand ambitions in mind as you try to excel at whatever entry level job you find. There is lots of fear and angst today in the field of journalism, and many young journalists complain that it is nearly impossible to make a secure career in the field (come to think of it, many older veteran journalists voice the same complaint). That is a very real concern: smart, hard-working journalists, with talent and a streak of luck, might find elusive success for themselves— interested editors, fascinating stories, engaged readers—and yet also find themselves unable to pay their rent and student loans. The equation, I fear, drives some of the talent away from journalism and into fields that are equally demanding and underpaid but at least allow the possibility of some stability: fields like human rights research and advocacy, humanitarian aid, NGO or government work, UN consulting, and the like.

There is an enduring thirst for international reporting, though, and I have seen a lot of talented and persistent journalists make impressive starts against long odds over the last five or ten years, living on a shoestring in places like Cairo or Beirut, and drawing attention with their excellent work. The flip side, of course, is that many freelancers are pushed by the bad economics of the business and the lack of commitment, in some cases, by their publications to take dangerous risks without any real institutional support. I encourage all journalists at all stages of their career to resist this pressure and demand that publications pay a living wage for the journalism they make and provide responsible support to those who work in war zones.

5. What was the last book you finished reading?

An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine.

6. What is the most overlooked threat to U.S. national interests?

None of the major threats the United States faces today amount to major strategic threats to core U.S. national interests; they pose complex problems that must be addressed creatively through sustained, costly engagement. Top among them are the security threats posed by a belligerent Russia and the failing or rigid states in the Middle East. But the biggest danger to U.S. interests these days is posed by the United States’ own overreaction, fueled by its own runaway security state, which dwarfs anything President Eisenhower had in mind when hewarned against the military-industrial complex. Today, an enormous portion of the U.S. economy is tied up in surveillance, control, and threat inflation. This vast roiling sea—people performing security theater at airports, agencies collecting data we can’t analyze—makes it all the harder to detect and prioritize actual threats.

7. What do you believe is the most inflated threat to U.S. national interests?

Jihadist violence and terrorism. Groups like the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) pose a real and tangible threat, but takfiri jihadist terrorism has been the single most overhyped phenomenon of our age. Murderous nihilists from Osama bin Laden, to Abu Musab al Zarqawi, to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi have swelled to importance far out of proportion to their very real, but strategically limited, ability to wreak mayhem. They are thugs, and in some instances have amassed power that demands a carefully planned, sustained, and powerful response. Don’t get me wrong; I’m not trying to say that they are not important or do not demand a serious U.S. policy and security response. But perhaps, because of the fears they endanger, these jihadists have proved capable of manipulating the United States and provoking reactions that suit their own ends. It is like the U.S. government stops thinking when it comes to takfiri jihadis. A Syrian dictator drops nerve gas on his own people and the United States announces, and then backs away from, a bombing campaign. But then a masked sadist taunts the president and murders an innocent citizen on video, and the United States is immediately ready to begin another war in the Arab world?

8. What is the most significant emerging global challenge?

Questions like this alway leave me floundering. Probably the biggest challenge is finding ways to spread sustainable prosperity into the quarters where it has been denied. In quasi-failing states like Egypt, that means the basics: housing, health care, literary, subsistence, jobs. In Europe, it means enabling the chronically unemployed to generate livelihoods and wealth. An unconscionable amount of wealth and waste has been generated over the last generation, and it has been far too inequitably spread around the world and within the wealthy societies at the top. This failure can propel instability anywhere: in an increasingly unequal United States, a struggling, polarized Euro-zone, and across the global south.

9. What would you research given two years and unlimited resources?

Identity formation in conflict. I have always been fascinated by the power of individual actors and ideological movements to drive change, for good as well as for ill. Often this power arises from a real or perceived sense of shared grievance that leads to the construction of a tangible community and, often, of a coherent ideology. At root, an ideological commitment and a personal identity serve as the cornerstone of any powerful community, and yet, these ideologies and identities are fluid and malleable. I would like to describe in as great detail as possible the factors that create and shift these identities. I have watched this process up close in Iraq and Lebanon, and I have read about it extensively in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. But there are countless examples from history.

10. Why should we read Once Upon a Revolution if we already know how Egypt’s uprising turned out?

It’s not a thriller! But, in a way, it is a mystery; the Tahrir Square revolution really was not supposed to happen, and even its most faithful partisans were shocked by how far they got. I followed a core group of revolutionary activists for four years; they were exceptional because they were the visionaries who, from the start, understood their quest was political and were not afraid to act as leaders even in an uprising that fetishized the idea of having no leaders. “Revolution” sounds grand and sweeping, but like any historical event, it occurred down in the weeds, in the details.

Individuals like Basem, the secular nationalist architect, and Moaz, the Muslim Brotherhood pharmacist, began with a mindset that would be familiar to most of us, and then made a series of improbably, often very imaginative and courageous, choices. Multiplied by thousands, that is what sparked the Tahrir Square revolution, and what will continue to cause upheaval in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world until abusive dictatorships are replaced with accountable governments that respect citizens. This book ends with the revolutionaries defeated by a new version of the old regime, but they are still fighting and, more importantly, the same grievances that sparked Tahrir are burning even more intensely today. Dictatorship might well prevail in the end, but we are not there yet. This is a human story, and it helps us understand why the last four years are only the opening chapter in what will be a generational struggle in Egypt.

Book launch roundup

I’m tying up loose ends from the first stage of the book tour and preparing to launch a variety of new projects. Here I’ve collected appearances about Egypt and the book from the recent spell.

Here & Now talked with me about the killings in Egypt over the uprising anniversary weekend. You can listen here.

The World asked about why Egypt has turned so firmly in an authoritarian direction, and wanted to know what Basem and Moaz are doing today. You can listen here.

Now Sisi is applying the same tools to the same problems that led to the Tahrir Square uprising.

“All those core grievances are still present,” Cambanis says, and “nothing, unfortunately, about Sisi’s methods suggest that he’s going to be able to resolve them.”

WGBH’s Greater Boston asked why so many Egyptians cheered Sisi’s rise to power. You can watch here.

During a long chat on “Uprising with Sonali” we talked about the arc of the last four years and how change can come to a complex state like Egypt. You can listen here.

Finally, Foreign Policy ran a long excerpt from the book’s closing chapter, about the week of the coup in July 2013.

After midnight, Morsi finally came on television. He rasped and ranted and shouted about his legitimacy. He didn’t relent an inch. It was the speech of a man who planned to go down fighting. It was a speech that comforted the men and women in Rabaa al-Adawiya Square who expected martyrdom. Moaz watched at a Brotherhood hospital with one of Morsi’s advisers.

“It’s all over,” the adviser said. “There might have been a way out, but not after this speech.”

“You know how a chicken keeps running around after you cut off its head?” Moaz remarked. “Morsi is like that.”

Politics & Prose

http://www.c-span.org/video/?323981-1/book-discussion-upon-revolution

You can also listen to the audio podcast of the talk from the Politics & Prose site, although I can’t find the link yet..

Egypt panel at Center for American Progress

A great session in Washington that featured retired General Jim Matthis, then the panel discussing the CAP report on Egypt (Brian Katulis, Mokhtar Awad, Amy Hawthorne, Michael Hanna), and then a discussion of my book with Steven Cook and Hardin Lang. The link below should lead to a YouTube video of the panel if the embedded file doesn’t work.

Book Launch: Leonard Lopate show

On Tuesday, Once Upon a Revolution went on sale. We kicked off with a great conversation on WNYC with guest host Aasif Mandvi. You can listen here.

Four years after Tahrir, what would make another uprising?

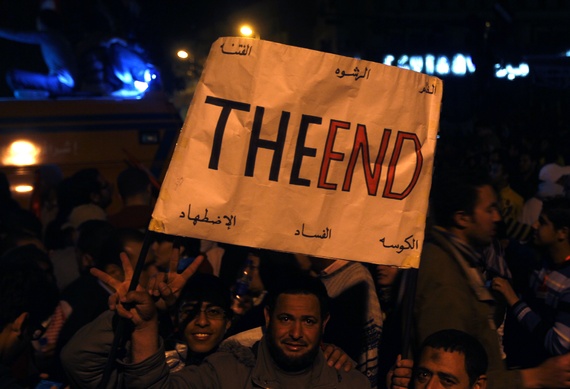

An anti-Mubarak protester in Tahrir Square, in November 2014 (Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters)

[Published in The Atlantic. Arabic translation available at Sasa Post.]

CAIRO—Four years after the revolution he helped lead, Basem Kamel has noticeably scaled back his ambitions. The regime he and his friends thought they overthrew after storming Tahrir Square has returned. In the face of relentless pressure and violence from the authorities, most of the revolutionary movements have been sidelined or snuffed out.

Egypt’s new strongman, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has injected new zeal and energy into the military establishment. He has established his rule using unprecedented amounts of force, including mass arrests and death sentences, and the elimination of freedoms that existed even under previous dictatorships. But he has also won considerable popularity, leading Egypt’s revolutionaries to seek new routes to change.

“Maybe in 12 years we will be back in the game,” Kamel told me during the January Coptic Christmas holidays, wearing a sweatsuit as he shuttled his kids to after-school sports. After some thought, the 45-year-old architect, who lives in southern Cairo, added a caveat: “Unless Sisi changes the rules.”

There’s been a dramatic downsizing of expectations since Sisi came to power in a military coup in July 2013 (he retired from the military and was elected president without any meaningful challenger in May 2014). But if the mood is grim among the activists who so recently turned Egypt’s power structure on its head, historical trends suggest that the victorious military establishment has plenty to worry about as well.

Sisi is younger, sharper, and more vigorous than Hosni Mubarak, but he’s applying the same tools to the same problems. A small, insular group of men makes all important decisions, from drafting the country’s new parliamentary-election law to managing the economy to deciding how to prosecute political prisoners. Foreign aid is a key pillar of support for the government. The main difference is in the faces around the top. Whereas Mubarak’s cabal included some rich civilians, Sisi relies almost exclusively on military men.

The problems are daunting no matter who leads Egypt. Unemployment is endemic. The nation can’t grow enough crops to feed itself, is running low on foreign currency, and runs up hefty bills importing energy and grain that it sells at heavily subsidized prices. There is no longer a free media in Egypt, and a regressive new law makes it almost impossible for independent NGOs to do their work. Political parties that don’t pay fealty to Sisi’s order are hounded and persecuted. One result of this repression is that there is no scrutiny of government policy, no new sources of ideas, and not even symbolic accountability for corruption, incompetence, and bad government decisions.

Egypt’s new ruler has made some shrewd moves. He has tweaked the food-subsidy system to reduce waste and corruption in bakeries, introducing a card system with points that allows consumers to spend their allowance on a variety of goods rather than lining up for bread that they end up throwing away. He paid a Christmas visit to the Coptic Cathedral in Cairo, the first time any Egyptian leader has done so since Gamal Abdel Nasser, reassuring some Christians after decades of increased marginalization of and violence against the beleaguered minority.

But unless he miraculously resolves the country’s underlying economic plight—a product of the previous six decades of authoritarian rule, most of it dominated by the military—Egypt will snap again sooner or later.

“Six months ago there was huge popular happiness with Sisi’s performance. Now already it is less,” said Ahmed Imam, a spokesman for Strong Egypt, one of the few active political opposition parties left in the country. “I believe in another six months you will find rage, and the rage will become public.”

* * *

The simplest way to understand the January 25, 2011 uprising against Mubarak’s military rule is as a rejection of a government that was both abusive and incompetent. Since the military coup that ended the monarchy and brought Nasser to power in 1952, Egyptian authoritarians have fared well enough when they provided tangible quality-of-life improvements, or when they leavened the disappointment of growing poverty with an increased margin of freedom. But by the end of his three decades in power, Mubarak provided neither: His corrupt government gutted services and the treasury, while his unaccountable military and police establishment freely meted out torture, arbitrary detention, and unfair trials.

According to his supporters and advisors, Sisi is gambling that he’ll pull off the kind of economic feats that characterized the apex periods of Egypt’s three major leaders in the modern era: Mubarak, Anwar Sadat, and Nasser.

So far, however, Sisi has needed to deploy draconian measures to keep control even at his moment of peak popularity. He has outlawed demonstrations. He has imprisoned tens of thousands, many for the simple offense of protesting. Old state security agents have returned to their old ways, humiliating dissidents by leaking their private phone calls to the media. Crackdowns target homosexuals, atheists, and blasphemers. Judges have sentenced to death hundreds of Muslim Brothers—until recently, members of an elected civilian ruling party—in shotgun trials that lasted a day or two and have made a mockery of Egypt’s once-respected judiciary. An activist from the secular April 6 Youth Movement recently had three years tacked on to his sentence because he dared ask about a Facebook page where the judge in his case had openly identified with Sisi’s regime and denigrated the revolutionaries, casting aside any pretense of judicial impartiality.

Such hardline tactics could reflect a military confidently in charge; many activists who subscribe to this view have chosen exile or a hiatus from public life. But the tactics also could reflect desperation: The old regime has won a reprieve, but it has to work much harder than before to keep a tenuous grip on power. In that case, the overwhelming chorus of support for Sisi could be just the prelude to another period of bitter disappointment and revolt.

Critical human-rights monitors continue to track government abuses, some from within Egypt despite the constant risk of arrest. A few youth and political movements continue to operate as well. The Revolutionary Socialists, the Youth Movement for Freedom and Justice, and April 6 all continue to organize, albeit on a modest scale; gone are the mass protests of 2011-2013. The Constitution Party, which includes some leading secular liberals, has been outspoken in its criticism of military rule. So has the Strong Egypt party, led by a former presidential contender and ex-Muslim Brother named Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, who has the distinction of having equally opposed abuses by Islamist and secular military regimes since Mubarak.

“Either the regime is reformed and resumes a democratic course, or its bad performance will provoke a revolution that will explode in its face,” Aboul Fotouh said in a recent interview in his home in a Cairo suburb. His party might run parliamentary candidates in the elections scheduled for March and April, but state security agents have made it impossible for the party to operate normally, canceling all 27 conference-room reservations it has made in the last three months—a favorite tactic resuscitated from Mubarak’s time.

* * *

Most of the leaders of the original uprising are in prison or exile. Some have been silenced, and some like, Kamel, seem willing to accept military repression as the necessary price for getting rid of the Muslim Brotherhood, which they considered the bigger threat. “Even knowing what I know today, I would say the Brotherhood is worse,” Kamel said.

Today, private and state media channels have become no-go zones for dissenting voices. Independent presenters like Yosri Fouda and comedian Bassem Youssef have gone off the air, and other one-time revolutionaries like Ibrahim Eissa have become shrill advocates for the regime.

In the four years that I’ve been reporting closely on Egypt’s transition from revolution to restoration, I’ve seen young activists go from stunned to euphoric to traumatized and sometimes defeated. I’ve seen stalwarts of the old regime go from arrogant and complacent to frightened and unsure to bullying and triumphalist. And yet, so far, the core grievances that drew frustrated Egyptians to Tahrir Square in the first place remain unaddressed. Police operate with complete impunity and disrespect for citizens, routinely using torture. Courts are whimsical, uneven, at times absurdly unjust and capricious. The military controls a state within a state, removed from any oversight or scrutiny, with authority over a vast portion of the national economy and Egypt’s public land. Poverty and unemployment continue to rise, while crises in housing, education, and health care have grown even worse than the most dire predictions of development experts. Corruption has largely gone unpunished, and Sisi has begun to roll back an initial wave of prosecutions against Mubarak, his sons, and his oligarchs.

Kamel has abandoned his revolutionary rhetoric of 2011 for a more modest platform of reform, working within the system. He was one of just four revolutionary youth who made it into the short-lived revolutionary parliament of 2012, and he helped found the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, one of the most promising new political parties after the fall of Mubarak.

He expects to run for parliament again with his party, but the odds are longer and the stakes lower. The parliament will have hardly any power under Sisi’s setup. Most of the seats are slated for “independents,” which in practice means well-funded establishment candidates run by the former ruling party network. The Muslim Brotherhood, the nation’s largest opposition group, is now illegal. Existing political parties can only compete for 20 percent of the seats, and most of them, like Kamel’s have dramatically tamed their criticisms.

“I think Sisi is in control of everything,” Kamel said. “Of course I am not with Sisi, but I am not against the state.”

That’s why he’s devoting his efforts to a training program for Social Democratic cadres, a sort of political science-and-organizing academy for activists and operatives that will take years to bear fruit. “It’s long-term work,” he said.

Still, something fundamental changed in January 2011, and no amount of state brutality can reverse it. Many people who before 2011 cowered or kept their ideas to themselves now feel unafraid.

“We want accountability, not miracles,” said Khaled Dawoud, spokesman for the Constitution Party. “We’re not asking for gay rights and legalized marijuana. We’re asking to stop torture in prisons.” Dawoud is a secular liberal activist who kept his integrity even during the period after Sisi’s coup when many of his peers cast their lot with the generals against the Islamists. He has been harassed by every faction, facing death threats and even a murder attempt by supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood.

In three years’ time, Egyptians took to the streets and saw three heads of state in a row flee from power: Mubarak, his successor Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, and President Mohammed Morsi. The legacies of the revolution are hotly contested, but one is indisputable: Large numbers of Egyptians believe they’re entitled to political rights and power. That remains a potent idea even if revolutionary forces and their aspiration for a more just and equitable order seem beaten for now.

In the worst of times under Mubarak, and before him Sadat and Nasser, mass arrests, executions, and the banning of political life kept the country quiet. But as Egypt heads toward the fourth anniversary of the January 25th uprisings, things are anything but quiet, despite the best efforts of Sisi’s state. Dissidents are smuggling letters out of jail. Muslim Brothers protest weekly for the restoration of civilian rule. Secular activists are working on detailed plans so that next time around, they’ll be able to present an alternative to the status-quo power. No one believes that this means another revolution is imminent, but the percolating dissatisfaction, and the ongoing work of political resistance, suggest that it won’t wait 30 years either.

“That’s our homework: to prepare a substitute,” said Mohamed Nabil, a leader in the April 6 movement who still speaks openly even though his group is now banned. “At the end Sisi is lying, and the Egyptian people will react. You never know when.”

Stay Thirsty asks about Egypt

A conversation with Stay Thirsty magazine.

STAY THIRSTY: In your new book, Once Upon A Revolution, you say that at the beginning of the 2011 Tahrir Revolution the revolutionaries spoke in bold strokes. What was it about their ideas that caught fire with the Egyptian people?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: They spoke out loud about their thirst for justice, breaking taboos that had been enforced, often with great violence, for generations. This revolution channeled an enormous current of anger and frustration, and it also tapped into a very primal simple hope for a better life. At its most elemental, Tahrir Square paired up two very powerful, if vague, sentiments: “You can’t crush me any more” and “Freedom!”

Egyptians had been told for generations that they were incapable of thinking for themselves. Only the regime was qualified to make political decisions. The police state enforced quietude through ubiquitous surveillance, and frequent torture, detention, and harassment. Rule was capricious and volatile, and it kept people off-balance. The people who filled Tahrir – to the shock of the ruling class and the secret police and their legions of thugs – said “Enough! We’re not scared of you anymore.” It was a real moment of calling out the naked emperor. Once people stopped being afraid, the only way to stop them was to kill them. Many Egyptians found this revelation tremendously empowering.

STAY THIRSTY: As the era of dictatorship under Hosni Mubarak came to an abrupt end, was there a genuine belief that a transition to democracy was really possible in Egypt?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: A window opened at the beginning of 2011 during which genuine democracy seemed possible. The transition really was contested. President Hosni Mubarak stepped down under pressure from the military. A popular revolt shook the ruling order, but in actual fact it was a military coup that unseated Mubarak. Still, while the military never lost power entirely, for the first year after Mubarak they were running scared. Again and again they capitulated to mass demonstrations. They were afraid of the secular young revolutionaries, they were afraid of the Muslim Brotherhood. The generals feared for a while that the ruling order would crumble entirely. But even at the beginning, the revolutionaries at the center of Tahrir Square knew they faced very long odds in their quest to end military domination of politics, hold the regime’s torturers and killers accountable, and dismantle the oppressive security state.

STAY THIRSTY: Leaderless revolts as we witnessed at Tahrir Square often collapse under their own weight. Will the ideals of the Tahrir Revolution nevertheless survive? Are they a true and lasting reflection of the will of the Egyptian people?

Tahrir Square (2011)

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: The ideals of the Tahrir Revolution are so attractive and unimpeachable that even Egypt’s new dictatorial ruler has adopted them, at least rhetorically. What’s not to like about “bread, freedom, social justice?” The more earth-shaking principals of Tahrir have survived as well, albeit under fire and among a beleaguered but brave vanguard: Think for yourself, dare to defy authority, believe in the near-impossible task of liberalizing an autocratic centralized state like Egypt’s. Arab autocrats believe they have the responsibilities of the ruler and ruled, and they see their subjects as fractious, infantilized, helpless without the strong hand of their father-leaders. Many of the opposition Islamists, including the Muslim Brotherhood, share this same fundamental outlook. The Tahrir Revolution swept that patronizing set of ideas away, in the belief that Egyptians were citizens, with the power and the right to shape a state of their own choosing. These are subversive ideas, and they took root with enough vigor that protesters demanded the fall of three regimes in the three years from 2011 to 2013. That experience cannot be wiped away. The glimpse of a frightened, deposed tyrant scuttling from his palace, scared of his own subjects, lingers in the minds of Egyptians even today, at a time when the old regime and its cronies are on top again. Never again can an Egyptian dictator take his reign for granted, and never again will Egyptians believe that they are powerless sheep, good only to walk silently within the wall of fear.

STAY THIRSTY: With a poor education system, persistent deep poverty and few resources, do knowledgeable people believe that the 2011 Tahrir Revolution will eventually turn into a sustainable government? Or, with the ouster of the Muslim Brotherhood and the rise of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power, are the revolutionaries pre-programmed to trust the Egyptian military and drift back into a Mubarak-like governmental structure?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: Hopes and expectations are much more muted than they were in 2011, when many revolutionaries really believed that root reforms were possible, and could quickly improve life for most of the country’s poor. Most of Mubarak’s governing structure has remained intact throughout the transitional period, or as some would call it, the revolution and the counterrevolution. The old regime is back in power, with a new and more ruthless leader and a security establishment that feels super-empowered to take revenge on the revolutionaries who challenged it. The revolutionaries themselves, for the most part, haven’t repudiated their dreams of a different kind of government – although some [like the liberal character in my book, Basem Kamel] have ruled out radical change and embraced a more incremental reform project. But a great deal of the public appears to have given up on bold ideas. Huge crowds joined Tahrir. Then later, huge crowds turned out for the Muslim Brotherhood, which dominated parliamentary elections and won the presidency in 2012. In the most recent chapter, the hugest crowds yet welcomed a coup led by Sisi, an army general, and then Sisi’s elevation to the civilian presidency. So public opinion has been fickle. It’s now clear to everybody who’s interested in change that improving Egypt’s government is an enormous undertaking. The institutions of state are powerful but inept and corrupt. Many of the most important ones, including the courts, the police, the army, have grown into autonomous fiefdoms that aren’t even entirely controlled by the strongman at the top. All this makes painfully elusive the idea of a government “of the people” that actually tries to help the poor and solve Egypt’s disastrous underlying problems: failed health care, education, housing and job market.

Tahrir Square (2011) (credit: Jonathan Rashad)

STAY THIRSTY: Now that the murder charges against Hosni Mubarak for killing 239 of the Tahrir protestors have been dropped by the Egyptian courts, will he re-emerge as the country’s strongman even though he is 86?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: Mubarak’s torch has passed to a younger, more vigorous retired general. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is Egypt’s strongman now, and he’s consolidating power with a more stifling and violent crackdown than anything Mubarak attempted during his 29 years in power. But the new military regime seems to be treating Mubarak as a sort of despot emeritus. They could have chosen to keep him in prison, or keep him quiet. But they’re letting him talk to the press, giving a sort of gloating impression. As if they’re so confident in the reincarnation of the old regime that they’re not worried about going too far and pushing people to revolt again.

STAY THIRSTY: How were your views of Egypt changed by writing Once Upon A Revolution? Are you hopeful for the people that led your story?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: The Egyptian revolutionaries defied my expectations not just of Egypt but of human nature. I had grown quite cynical about the possibility of humans anywhere to undergo great change, and I certainly doubted that an apathetic public could suddenly get politicized and try to seize control of its destiny. I felt this way about humans in general, and Egypt seemed like a place whose public had been completely drummed into submission – not that people liked it, but they seemed to have given up a sense of possibility. What happened was really mind-blowing to me. A small group of people stood up against every kind of pressure to submit: not just police torture and regime harassment, but their own families telling them to stay home and shut up. They didn’t stay home, and then hundreds, maybe millions of people broke out of their habitual silence and acquiescence to protest or speak out or otherwise engage in politics. That’s a level of transformation that most people never experience in their adult lifetimes. Here, a huge number of people did it, at great risk. I will never again assume that just because something like the survival of a dictatorship is likely means it is guaranteed. I still have great hope for the individuals who made this daring creative leap. And I can’t give up completely on the chances for their grand project for Egypt. So long as these revolutionaries are still agitating and cogitating, be it in prison, in exile, or underground, their dreams might yet come to fruition. Not likely, perhaps, but not doomed.

STAY THIRSTY: When we look at the Arab Spring and its aftermath, when we look at the rise of ISIS and the role it is playing in Syria and Iraq and when we look at the role that Iran and Saudi Arabia are playing in the Arab Middle East, do you believe the DNA of the people in that region hardwires them for dictatorship or democracy?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: A kind of determinism or essentialism informs a lot of prejudiced thinking about ethnic or racial destiny, and I’d like to see us move away from that kind of thinking in our effort to understand why different countries end up with different kinds of governments. No group of people anywhere on earth is genetically programmed or otherwise predestined for the system of government under which it lives. Especially people living under autocratic systems, who have almost no mechanisms through which to voice their consent or shape the way they governed. I don’t mean to say that individuals have no responsibility. Often, in violent regimes, it’s a life-and-death struggle simply to avoid being complicit in regime crimes. That said, there are deep structural problems in governance across the Arab world, and there are many malignant forces to content with including takfiri jihad, rabid nationalism, and intolerance of minorities. It is very hard to force system change, especially against entrenched interest groups, like the Egyptians military, that are wealthy powerful, and violent. I think it will be a long struggle for Egypt to achieve some version of democracy. Same for war-ravaged polities like Syria and Iraq. Tunisia seems to have a good chance of developing a decent system. And perhaps unexpectedly, Iran has potential because despite its oppressive theocracy it has developed mature institutions and educated citizens, who could form the bedrock of a future democracy.

STAY THIRSTY: Is the world safer under the dictator you know or under a work-in-progress fledgling democracy? Is there any chance that the Middle East will move to a more orderly political environment or are we at the beginning of a very messy and disorderly period that will sacrifice vast numbers of lives and huge amounts of treasure without a clear outcome? Will the tyrants or the extremists eventually be the victors or will the tribal leaders seize control of their particular territories and dismantle the nation-states of the region?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: Change is unsettling, not just to the powerful but to the regular people living with uncertainty and often suffering real privation above and beyond the pain and poverty to which they were already subjected. I’m a fervent believer that repressive unaccountable regimes built on fear are unsustainable over the long run. Many players, including the governments of the US and Saudi Arabia, seem to be putting their money on a bet for stability in the form of reconstituted authoritarian dictatorships. These bets are doomed to fail not simply because these regimes are unjust and morally unpalatable; it’s because they fail on the simple metric of providing anything for their people. A dictator who keeps the people fed and clothed might stand a chance; but not a dictator who humiliates the population while consistently lowering its standard of living. There might be another waiting period in places like Egypt, where Sisi could buy some years, even a decade, before the next uprising. One way or another, across the region we’re going to see a long and turbulent transition toward new, more accountable and inclusive political systems. They might not necessarily be democracies; they might even be outright dictatorships but ones that are more stable because they’re built on a wider coalition. There’s a slim chance that some of the artificial borders drawn after World War I will change as a result of wars like the one waged by ISIS, but I think it’s unlikely. Even these gummy borders have taken on a sort of logic and momentum of their own, and I think the more likely outcome is a renegotiation of national pacts within existing borders.

Protesting in Tahrir Square (2011)

STAY THIRSTY: You live in Beirut and have written about its many great advantages in spite of its lack of government and police force. Is Beirut a model for how we can expect successful cities in the Arab world to function in the future?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: It might be a model but it’s not an inspiring one – more of a muddled least worst of a bunch of bad possibilities. I’ve heard the same refrain a lot: “We’re not going to be another Lebanon!” I heard it in Iraq immediately after the US invasion in 2003, and I heard it from Syrians after their civil war quickened in 2011. Now Iraq has adopted some of the worst aspects of Lebanon’s power-sharing model, which is essentially a form of institutionalized gridlock that guarantees nothing important can ever be accomplished by the government but which minimizes the chance of another sectarian civil war. Some Syrian revolutionaries who dreamed of a democracy now say they’d be happy to turn out like Lebanon. I don’t think this system would be anybody’s first choice, but it’s certainly better than civil war or a violent, centralized dictatorship. But try educating your children or treating a serious disease here, and you see the pitfalls of living in a nation without a state.

STAY THIRSTY: If you were given the opportunity to reshape the Middle East, what would it look like in twenty-five years?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: I could tell you about things I’d like to see happen, but I cannot begin to answer that question not least because no single entity, not even a modern superpower or the Ottoman Caliphate, had that much power to shape events. I’d like to see the US be less reactive and less supportive of repressive corrupt regimes out a misplaced interest in stability. I’d like to see a curtailing of the mostly malign regional influence of Iran, which supports a lot of militias, and Saudi Arabia, whose money underlies the growing reach of religious extremism. I’d like to see the rise of a credible, authentic, locally supported culture of rights, due process, rule of law, citizenship, and pluralism, and an end to cults of personality and police states. It’s not that different than the kind of freedom, equality, economic opportunity and just institutions that I’d like to see flourish everywhere.

STAY THIRSTY: What can we expect next from you?

THANASSIS CAMBANIS: I don’t have any immediate plans for another book, but I didn’t plan on writing this one until January 25, 2011, when I realized I had no other choice. I’ll be keeping an eye on Egypt no matter what, but for the next few years I plan to focus on Lebanon and Syria. There’s a lot of fascinating dynamics playing out in the Syrian civil war, and like the Arab revolts overall, they’re part of a very long term process of political reinvention. New ideas are slowly coming to maturity: ideas about citizenship, governance, rights (along with a slough of not-so-appealing ideas about majoritarian rule and religious triumphalism). So are new power centers and networks. All these revolutionaries and activists are going to be at the core of the next generation’s elite. I’m excited to see what difference that makes. I’m also trying to take a respite from a decade’s focus on political struggles and war, with a line of reporting about culture and urban life in Beirut. Lots of the same questions, but played out in struggles that don’t usually involve killing.

Publisher’s Weekly review

Another review out in Publisher’s Weekly of Once Upon a Revolution.

ONCE UPON A REVOLUTION

As the heady days of revolution in Tahrir Square recede further into the past, liberal democracy in Egypt seems increasingly like a pipe dream. Beirut-based journalist Cambanis (A Privilege to Die) follows two leaders of the uprising from the beginnings of their political involvement to the military coup that overthrew Mohamed Morsi. Basem, an unassuming architect, becomes one of the few liberal members of parliament, while Moaz, a Muslim Brother, grows increasingly disenchanted with political Islam. Cambanis eloquently describes post-Mubarak Egypt and the “chaos coursing below the surface, but open conflict still just over the horizon,” as well as the “inability of secular and liberal forces to unify and organize,” which left the political field open to the military apparatus and the secretive Islamists. Crushed by arbitrary military edicts and ascendant puritanism, Egypt’s nascent civil society stalled and sputtered while its freewheeling press degenerated into “a brew of lies, delusion, paranoia, and justification.” The people Cambanis shadows never lose hope, exactly, but he makes clear that they feel as if they are spitting into the wind, struggling to enunciate what the revolution accomplished. Agent: Wendy Strothman, Strothman Agency. (Feb.)

Booklist reviews “Once Upon a Revolution”

Middle East reporter Cambanis, who writes the “Internationalist” column for the Boston Globe and regularly contributes to the New York Times, offers a gripping portrayal of the forces that led to the eruption in Tahrir Square in Egypt on January 25, 2011. His reporting and analysis also move out from that event, considering a revolution that has not yet ended. He compares this revolution to the French Revolution, a long time coming and a long time continuing. Cambanis’ in-depth examination started, he says, with his on-the-ground reporting during the uprising, finding people in the square who were willing to continue to talk with him. The richness of his reporting informs his book, but it is the narrative nonfiction frame that humanizes the account and makes it more accessible. He focuses on two unlikely revolutionaries: Basem Kamel, a middle-class architect who came late to politics at 40, and Moaz Abdelkarim, a pharmacist and career activist. By tracing Kamel’s and Abdelkarim’s varying backgrounds, Cambanis manages both to give readers two insiders’ views of Egypt in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and to trace the origins of Tahrir Square and its ripples. Cambanis is master of the compelling detail: for example, in relating that Kamel was born in 1937, he notes that this was the year King Farouk I was crowned, a king who ate oysters by the hundred in his palace while his people endured WWII bombings. Wonderfully readable and insightful.

— Connie Fletcher

[Original here.]