Four years after Tahrir, what would make another uprising?

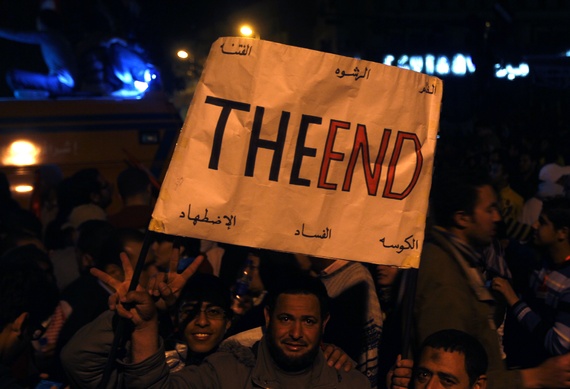

An anti-Mubarak protester in Tahrir Square, in November 2014 (Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters)

[Published in The Atlantic. Arabic translation available at Sasa Post.]

CAIRO—Four years after the revolution he helped lead, Basem Kamel has noticeably scaled back his ambitions. The regime he and his friends thought they overthrew after storming Tahrir Square has returned. In the face of relentless pressure and violence from the authorities, most of the revolutionary movements have been sidelined or snuffed out.

Egypt’s new strongman, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has injected new zeal and energy into the military establishment. He has established his rule using unprecedented amounts of force, including mass arrests and death sentences, and the elimination of freedoms that existed even under previous dictatorships. But he has also won considerable popularity, leading Egypt’s revolutionaries to seek new routes to change.

“Maybe in 12 years we will be back in the game,” Kamel told me during the January Coptic Christmas holidays, wearing a sweatsuit as he shuttled his kids to after-school sports. After some thought, the 45-year-old architect, who lives in southern Cairo, added a caveat: “Unless Sisi changes the rules.”

There’s been a dramatic downsizing of expectations since Sisi came to power in a military coup in July 2013 (he retired from the military and was elected president without any meaningful challenger in May 2014). But if the mood is grim among the activists who so recently turned Egypt’s power structure on its head, historical trends suggest that the victorious military establishment has plenty to worry about as well.

Sisi is younger, sharper, and more vigorous than Hosni Mubarak, but he’s applying the same tools to the same problems. A small, insular group of men makes all important decisions, from drafting the country’s new parliamentary-election law to managing the economy to deciding how to prosecute political prisoners. Foreign aid is a key pillar of support for the government. The main difference is in the faces around the top. Whereas Mubarak’s cabal included some rich civilians, Sisi relies almost exclusively on military men.

The problems are daunting no matter who leads Egypt. Unemployment is endemic. The nation can’t grow enough crops to feed itself, is running low on foreign currency, and runs up hefty bills importing energy and grain that it sells at heavily subsidized prices. There is no longer a free media in Egypt, and a regressive new law makes it almost impossible for independent NGOs to do their work. Political parties that don’t pay fealty to Sisi’s order are hounded and persecuted. One result of this repression is that there is no scrutiny of government policy, no new sources of ideas, and not even symbolic accountability for corruption, incompetence, and bad government decisions.

Egypt’s new ruler has made some shrewd moves. He has tweaked the food-subsidy system to reduce waste and corruption in bakeries, introducing a card system with points that allows consumers to spend their allowance on a variety of goods rather than lining up for bread that they end up throwing away. He paid a Christmas visit to the Coptic Cathedral in Cairo, the first time any Egyptian leader has done so since Gamal Abdel Nasser, reassuring some Christians after decades of increased marginalization of and violence against the beleaguered minority.

But unless he miraculously resolves the country’s underlying economic plight—a product of the previous six decades of authoritarian rule, most of it dominated by the military—Egypt will snap again sooner or later.

“Six months ago there was huge popular happiness with Sisi’s performance. Now already it is less,” said Ahmed Imam, a spokesman for Strong Egypt, one of the few active political opposition parties left in the country. “I believe in another six months you will find rage, and the rage will become public.”

* * *

The simplest way to understand the January 25, 2011 uprising against Mubarak’s military rule is as a rejection of a government that was both abusive and incompetent. Since the military coup that ended the monarchy and brought Nasser to power in 1952, Egyptian authoritarians have fared well enough when they provided tangible quality-of-life improvements, or when they leavened the disappointment of growing poverty with an increased margin of freedom. But by the end of his three decades in power, Mubarak provided neither: His corrupt government gutted services and the treasury, while his unaccountable military and police establishment freely meted out torture, arbitrary detention, and unfair trials.

According to his supporters and advisors, Sisi is gambling that he’ll pull off the kind of economic feats that characterized the apex periods of Egypt’s three major leaders in the modern era: Mubarak, Anwar Sadat, and Nasser.

So far, however, Sisi has needed to deploy draconian measures to keep control even at his moment of peak popularity. He has outlawed demonstrations. He has imprisoned tens of thousands, many for the simple offense of protesting. Old state security agents have returned to their old ways, humiliating dissidents by leaking their private phone calls to the media. Crackdowns target homosexuals, atheists, and blasphemers. Judges have sentenced to death hundreds of Muslim Brothers—until recently, members of an elected civilian ruling party—in shotgun trials that lasted a day or two and have made a mockery of Egypt’s once-respected judiciary. An activist from the secular April 6 Youth Movement recently had three years tacked on to his sentence because he dared ask about a Facebook page where the judge in his case had openly identified with Sisi’s regime and denigrated the revolutionaries, casting aside any pretense of judicial impartiality.

Such hardline tactics could reflect a military confidently in charge; many activists who subscribe to this view have chosen exile or a hiatus from public life. But the tactics also could reflect desperation: The old regime has won a reprieve, but it has to work much harder than before to keep a tenuous grip on power. In that case, the overwhelming chorus of support for Sisi could be just the prelude to another period of bitter disappointment and revolt.

Critical human-rights monitors continue to track government abuses, some from within Egypt despite the constant risk of arrest. A few youth and political movements continue to operate as well. The Revolutionary Socialists, the Youth Movement for Freedom and Justice, and April 6 all continue to organize, albeit on a modest scale; gone are the mass protests of 2011-2013. The Constitution Party, which includes some leading secular liberals, has been outspoken in its criticism of military rule. So has the Strong Egypt party, led by a former presidential contender and ex-Muslim Brother named Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, who has the distinction of having equally opposed abuses by Islamist and secular military regimes since Mubarak.

“Either the regime is reformed and resumes a democratic course, or its bad performance will provoke a revolution that will explode in its face,” Aboul Fotouh said in a recent interview in his home in a Cairo suburb. His party might run parliamentary candidates in the elections scheduled for March and April, but state security agents have made it impossible for the party to operate normally, canceling all 27 conference-room reservations it has made in the last three months—a favorite tactic resuscitated from Mubarak’s time.

* * *

Most of the leaders of the original uprising are in prison or exile. Some have been silenced, and some like, Kamel, seem willing to accept military repression as the necessary price for getting rid of the Muslim Brotherhood, which they considered the bigger threat. “Even knowing what I know today, I would say the Brotherhood is worse,” Kamel said.

Today, private and state media channels have become no-go zones for dissenting voices. Independent presenters like Yosri Fouda and comedian Bassem Youssef have gone off the air, and other one-time revolutionaries like Ibrahim Eissa have become shrill advocates for the regime.

In the four years that I’ve been reporting closely on Egypt’s transition from revolution to restoration, I’ve seen young activists go from stunned to euphoric to traumatized and sometimes defeated. I’ve seen stalwarts of the old regime go from arrogant and complacent to frightened and unsure to bullying and triumphalist. And yet, so far, the core grievances that drew frustrated Egyptians to Tahrir Square in the first place remain unaddressed. Police operate with complete impunity and disrespect for citizens, routinely using torture. Courts are whimsical, uneven, at times absurdly unjust and capricious. The military controls a state within a state, removed from any oversight or scrutiny, with authority over a vast portion of the national economy and Egypt’s public land. Poverty and unemployment continue to rise, while crises in housing, education, and health care have grown even worse than the most dire predictions of development experts. Corruption has largely gone unpunished, and Sisi has begun to roll back an initial wave of prosecutions against Mubarak, his sons, and his oligarchs.

Kamel has abandoned his revolutionary rhetoric of 2011 for a more modest platform of reform, working within the system. He was one of just four revolutionary youth who made it into the short-lived revolutionary parliament of 2012, and he helped found the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, one of the most promising new political parties after the fall of Mubarak.

He expects to run for parliament again with his party, but the odds are longer and the stakes lower. The parliament will have hardly any power under Sisi’s setup. Most of the seats are slated for “independents,” which in practice means well-funded establishment candidates run by the former ruling party network. The Muslim Brotherhood, the nation’s largest opposition group, is now illegal. Existing political parties can only compete for 20 percent of the seats, and most of them, like Kamel’s have dramatically tamed their criticisms.

“I think Sisi is in control of everything,” Kamel said. “Of course I am not with Sisi, but I am not against the state.”

That’s why he’s devoting his efforts to a training program for Social Democratic cadres, a sort of political science-and-organizing academy for activists and operatives that will take years to bear fruit. “It’s long-term work,” he said.

Still, something fundamental changed in January 2011, and no amount of state brutality can reverse it. Many people who before 2011 cowered or kept their ideas to themselves now feel unafraid.

“We want accountability, not miracles,” said Khaled Dawoud, spokesman for the Constitution Party. “We’re not asking for gay rights and legalized marijuana. We’re asking to stop torture in prisons.” Dawoud is a secular liberal activist who kept his integrity even during the period after Sisi’s coup when many of his peers cast their lot with the generals against the Islamists. He has been harassed by every faction, facing death threats and even a murder attempt by supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood.

In three years’ time, Egyptians took to the streets and saw three heads of state in a row flee from power: Mubarak, his successor Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, and President Mohammed Morsi. The legacies of the revolution are hotly contested, but one is indisputable: Large numbers of Egyptians believe they’re entitled to political rights and power. That remains a potent idea even if revolutionary forces and their aspiration for a more just and equitable order seem beaten for now.

In the worst of times under Mubarak, and before him Sadat and Nasser, mass arrests, executions, and the banning of political life kept the country quiet. But as Egypt heads toward the fourth anniversary of the January 25th uprisings, things are anything but quiet, despite the best efforts of Sisi’s state. Dissidents are smuggling letters out of jail. Muslim Brothers protest weekly for the restoration of civilian rule. Secular activists are working on detailed plans so that next time around, they’ll be able to present an alternative to the status-quo power. No one believes that this means another revolution is imminent, but the percolating dissatisfaction, and the ongoing work of political resistance, suggest that it won’t wait 30 years either.

“That’s our homework: to prepare a substitute,” said Mohamed Nabil, a leader in the April 6 movement who still speaks openly even though his group is now banned. “At the end Sisi is lying, and the Egyptian people will react. You never know when.”

Inside the Three-Way Race for Egypt’s Presidency

Leading Egyptian presidential candidates Amr Moussa, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, and Mohamed Morsi. / Reuters, AP

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

CAIRO — Egypt’s first real presidential contest ever, for which the candidates met last night for the Arab world’s first-ever real presidential debate, has all the makings of a genuinely interesting fight. The front-runners nicely capture a wide stretch of the spectrum, while leaving out the extremes. Voter interest appears high, and the military rulers seem unlikely to allow major fraud based on their record with parliamentary elections.

But enthusiasm about the debate should not obscure the unsatisfying circumstances of the presidential election, which itself does not guarantee a full transition to civilian rule or democracy.

The president’s powers still have not been delineated, and the significance of the race and its victor could be heavily tarnished by future decisions about the assembly that will write the next constitution, among other unresolved questions about whether Egypt will have a presidential, parliamentary, or hybrid system.

Islamists have proven themselves to be the dominant political bloc, garnering more than two-thirds of the vote in parliamentary elections earlier this year. The winner of the presidential race, even if he is secular, will owe his victory to Islamist voters, and will have to govern in tandem with a parliament that has a veto-proof Islamist majority. Islamist politics are malleable and by no means monolithic, but they will drive the political agenda after decades of total exclusion.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, has heavily manipulated the process, deepening its unaccountable and authoritarian mechanisms of control. Crony-packed courts and the presidential election commission have made a series of arbitrary decisions. Egypt’s next government will have to negotiate artfully to wrest the most important powers out of the hands of generals.

The campaign has galvanized Egyptians. This week, the candidates crisscrossed the countryside in bus caravans, and thousands turned out in even the minutest villages.

“He has a special charisma,” gushed an English teacher named Ahmed Abdel Lahib, during a pit stop by the Amr Moussa campaign in a Nile Delta hamlet called Mit Fares. “Egypt needs a man like him,” he said of the former Arab League secretary-general.

Hundreds of men thronged the candidate, shouting, “Purify the country!” and “We want to kiss you!” In his tailored suit, and carrying the patrician demeanor he honed over decades as Egypt’s foreign minister and then Arab League chief, Musa clambered onto a makeshift stage for his short stump speech (fix agriculture, the economy, and health care, long live Egypt!). Men pushed over chairs and slammed one another into the walls of the narrow alley to get closer to Moussa and touch his sleeve.

The oaths of loyalty felt a tad staged and excessive, but similar displays characterized all the major candidate rallies, and could reflect the old authoritarian rallies, or a desire for a galvanizing leader like Gamal Abdel Nasser, the nationalist colonel who took power in a 1952 coup, or simply the enthusiasm of voters who for the first time in their lives will likely get to choose their president.

Moussa has presented himself as a secular elder statesman who can stand against what he portrays as a power-hungry Islamist tide, personified by the other two front-runners: the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi and the ex-Muslim Brother Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. It is Aboul Fotouh who most worries Moussa’s strategists: he is giving the former minister a run for first place, marketing himself as potential bridge candidate, a “liberal Islamist” who can appeal to Islamists as well as the secular nationalists and revolutionaries who are wary of Moussa’s connections to the old regime.

Thousands of fans in the market town of Senbelawain waited hours on a recent night for Aboul Fotouh, who seems perpetually delayed by traffic (he was late for the historic presidential debate for the same reason). When he arrived, the retired doctor was greeted like a rock star with swoons and chants. Bearded Salafis and women in full-face-covering niqabs jostled with clean-shaven students.

Aboul Fotouh is a more gripping orator than Moussa, with a gruff, gravelly voice that he controls well, shifting cadence to maintain his audience’s attention. “If this country succeeds, the whole Islamic world succeeds,” Aboul Fotouh shouted, provoking cries of exultation. He talked extensively about sharia, in a way apparently calculated to burnish his Islamist credentials while reassuring his left flank that he opposes such literal interpretations as severing the hands of thieves. Aboul Fotouh’s stump speech played to his Islamist base rather than to his revolutionary and secular sympathizers.

A Muslim Brotherhood member in the audience named Yousef Eid Hamid, 38, said he was campaigning for Aboul Fotouh in defiance of his organization’s strict orders to vote for Morsi. “We are not machines,” he said. “You cannot love a candidate, and then just change.”

Backroom deals with the military will likely be decisive in determining how the winner can govern, but retail politics seem to be taking root for now. During Thursday night’s debate, the two front-runners, Moussa and Aboul Fotouh, dug at each other’s records. Aboul Fotouh portrayed Moussa as a corrupt, weak stooge for Mubarak who will continue the old regime’s authoritarian ways. Moussa attacked Aboul Fotouh as a fire-and-brimstone Islamist who founded a radical group in the 1970s and now disingenuously presents himself as a moderate.

Egyptians crammed cafes to watch. During a half-time walkthrough (the debate lasted more than four hours, from 9:30 p.m. to 2 a.m.) at the Boursa pedestrian arcade behind the Cairo stock exchange, I met several people who had voted for the Muslim Brotherhood for parliament but were leaning toward the anti-Islamist Moussa for president.

“I will give the Muslim Brotherhood domestic policy, but I want to keep them far away from security and foreign policy,” said Abdelrahim Abdullah Abdelrahim, 44, an import-export businessman built like a bouncer. “These Islamists want to march on Al Quds” — Jerusalem — “and wage war. It’s not the time for this.”

He went on to mock the Salafi legislator who tried to sound the call to prayer in parliament, and his Noor Party colleague who tried to claim his nose job bandage was really the scar from a politically motivated assault. “People are more tired than before,” Abdelrahim said as he lost another round of dominoes to a friend.

At the presidential rallies in the Delta, I met numerous voters who were shopping or just checking out the opposition. Leftist revolutionaries, committed to minor candidates guaranteed not to reach the second round, listened to stump speeches to consider whom they’d be willing to hold their noses and vote for in a runoff. Confirmed skeptics came, in case they might change their minds.

Arguments broke out. At the end of one Moussa pit stop in Dikirnis, an older man dismissed the candidate as a “felool,” or remnant of the old regime. Another man pushed him hard in the abdomen: “He is not a felool! Amr Moussa is a great man!” The critic scuttled off to his nephew’s pastry shop, where he continued his invective against Moussa. The nephew, 37-year-old Ahmed Burma, smiled benevolently. “My uncle jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon,” he said. “But I’m supporting Amr Moussa. I run a business with 90 employees. Let’s give this guy a chance to work.”

Still, the polls and predictions are little more than guesswork. Most of the voters live without internet or phones and are beyond the reach of the campaigns’ opinion researchers. Egypt has had only one real election in its modern history: the parliamentary ballot that concluded this January. Twenty-seven million people voted, more than two-thirds of them for Islamist parties.

Even with the Islamist vote split between Aboul Fotouh and the Brotherhood’s Morsi, it’s all but assured that one of them will face Moussa in the runoff June 16 and 17. Morsi might fare better than many analysts seem to think, as the Brotherhood deploys its formidable get-out-the-vote operation, which no other campaign can currently match.

The Islamists in parliament haven’t acquitted themselves well, wasting time on fringe religious debates while the economy sinks, deferring to the army on crucial issues such as military trials for civilians, and alienating almost every major constituency in the country other than their own by trying to impose a constitutional convention packed with Salafist and Brotherhood members.

If turnout is as high as it was for parliament (and it might be higher, since the president has always been the commanding figure in Egypt’s modern political system), Moussa would need to convince more than 6 million people, a full third of those who voted Islamist for parliament, to switch allegiance and vote for him. His advisers believe that’s possible.

They also seem to think that Moussa’s year-long bus tour of rural areas will pay dividends, and that their basic selling point resonates with common voters: a pair of safe, experienced hands for a transition.

Nonetheless, Moussa’s strategy smacks of secular liberal wishful thinking, a common affliction among Egypt’s veteran political class in a year and a half of dynamic change. It might just work out for him, but an equally likely scenario would have the voters that propelled Islamists to parliament eager to give someone with their values more of a chance for success than has been allowed by three months of parliamentary machinations under the shadow of the military.