Aleppo’s fall is our shame, too

Syrian residents, fleeing violence elsewhere in Aleppo, arrive in the city’s Fardos neighborhood Tuesday. STRINGER/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Published in The Boston Globe.]

As the last rebel neighborhoods in Aleppo fell this week, Samantha Power, America’s ambassador to the United Nations, excoriated Russia, Syria, and Iran for authoring what will prove to be the signal atrocity of our time.

“Are you truly incapable of shame?” Power asked. “Is there no act of barbarism against civilians, no execution of a child that gets under your skin?”

Hundreds of thousands chose to stay in what they proudly called “Free Aleppo,” eschewing safe routes when they still existed and vowing to preserve their alternative to Syrian President Bashar Assad even if it meant death.

This week, that horrific choice materialized. Assad’s regime destroyed rebel Aleppo step by step, using Russian airpower; legions of militiamen from Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen and Lebanon; and the barrel bomb, another of the war’s sad innovations. Syrian rebels in Aleppo had warned for a year and a half that a siege was inevitable unless their backers, including the United States, provided them at least with air support and a steady supply of bullets and cash.

Western officials decried the unfolding tragedy in Aleppo, but their actions guaranteed this week’s genocidal denouement. The United States withheld basic support to vetted rebels. Turkey diverted its proxies to deal with the Kurdish problem on the border. And the West continued to negotiate after Russia engaged in blatant subterfuge and spectacular war crimes, emboldening the scorched earth campaign in Aleppo.

Ambassador Power is right to ask about shame. Ultimately, a great share of it will belong to her government and the other fair-weather “friends of Syria” who supported the country’s revolution only half-heartedly — enough to prolong it while also sealing its failure.

For a quarter-century, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the international order trended toward more accountability and cooperation. Sure, international law is most often honored in the breach, and institutions like the International Criminal Court have no enforcement arm. But for a time, the international community was a meaningful forum with a conscience, and it created new doctrines like the “responsibility to protect,” which held that any state that wantonly murders its citizens forsakes its sovereignty. New norms took root: War crimes still occurred but invited wider and wider condemnation, military interventions required legal justification, and humanitarian concerns achieved the status of core national interests.

Altruism and self-interest were crucially intertwined in doctrines that aimed to make the world a less cruel but also a more stable place. We opposed torture and war crimes elsewhere because they’re dead wrong, but also because we don’t want out own citizens subjected to them.

Today, an opposite calculus is in effect. We don’t stand against the leveling of Aleppo because we reserve the right not to be judged for similar crimes. It will be difficult for America to invoke human rights as a cornerstone of foreign policy.

On a human level, Aleppo’s fall is nearly unbearable. Citizens, volunteer doctors, children, and others are hunted from neighborhood to neighborhood in the city’s shrinking Assad-free patch. Shells and bombs fall indiscriminately. Those who flee risk massacre by pro-government militias. If they make it to safety, they face torture or even death in Assad’s gulag. We can hear their pride and desperation in videos, tweets, and phone calls, often broadcast live as the battle for Aleppo climaxes.

Many of us knew the end was coming, but when it finally did this week, it was a sucker punch to the gut. Even if we expected it, we hoped Aleppo would not finish this way.

While this personalized violence is horrifying, it is hardly unique to Aleppo. Yet this apex of expedient, Machiavellian criminality caps off a long period when norms have eroded and international law has been undermined by its most important sponsors. Everyone has a stake in the erasure of Aleppo — not just the trigger-pulling governments in Damascus, Tehran, and Moscow.

Aleppo has thrived for millennia and one day will recover as a city. The prognosis is not as good for the ideas we have cherished since World War II and which we hoped would prevent any repeats.

Syria’s war will continue for some time — probably years. But barring a major and unexpected global shift, its outcome is no longer in doubt. Assad’s government will stay in power, slowly re-extending its reach over the entire territory of Syria and cobbling together some new version of the terror-and-torture apparatus through which it coerced the compliance of its population until 2011.

We watched the block-by-block incineration of a free city. Its rubble will build the foundation of our century’s pessimistic new world order.

What Aleppo Is

Boys make their way through the rubble of damaged buildings in the rebel held area of al-Kalaseh neighborhood of Aleppo, Syria, September 29, 2016. Reuters/Abdalrhman Ismail

[Published in The Atlantic.]

BEIRUT—For at least a year before the summer of 2016, civilians and fighters in rebel-held East Aleppo prepared for a siege they believed was both avoidable and inevitable. Correctly, it turns out, they calculated that the opposition’s bankrollers and arms suppliers—the United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other “friends of Syria”—cared little for the well-being of civilians in rebel-held areas. Through the spring, contacts inside Aleppo prepared for the siege, expending minimal effort on appeals to the international community, which they assumed would be futile.

For all the world-weary resignation of the opposition fighters and other residents of rebel Aleppo, they have a well-earned pride in what they’ve done. They’ve maintained their hold on half of the jewel of Syria, and under withering assault, have cobbled together an alternative to Bashar al-Assad’s rule. “From the beginning of the revolution, we held Aleppo as the role model of the liberated city, that holds free elections, has an elected city council, and elected local committees that truly represent the people,” Osama Taljo, a member of the rebel city council in East Aleppo, explained over the phone after the siege began in earnest. “We insisted to make out of Aleppo an exemplar of the free Syria that we aspire to.”

Unfortunately, Aleppo has become an exemplar of something else: Western indifference to human suffering and, perhaps more surprisingly, fecklessness in the face of a swelling strategic threat that transcends one catastrophic war.

The last few weeks have piled humiliation upon misfortune for Aleppo, one of the world’s great cities, and already a longtime hostage of Syria’s never-ending conflict. Aided by the Russian military and foreign sectarian mercenaries, Syrian forces encircled East Aleppo over the summer. Rebels briefly broke the siege, but Assad’s forces fully isolated them just as Russia and the United States put the finishing touches on a dead-on-arrival ceasefire agreement that, contrary to its stated purpose, ushered in one of the war’s most violent phases yet. Instead of a cessation of hostilities, Syria witnessed an acceleration of the war against civilians, with East Aleppo as the showcase of the worst war-criminal tactics Assad has refined through more than five years of war.

Sieges violate international law, as well as specific United Nations resolutions, that, on paper, guarantee access to humanitarian aid to all Syrians but which in practice the government has disregarded. Aleppo—the biggest prize yet for Assad—has also been subjected to his most destructive assault. Throughout East Aleppo, Syrian or Russian aircraft have ruthlessly bombed civilians, singling out all healthcare facilities and first-responder bases. Bombs have ravaged well-known hospitals supported by international aid groups, along with the facilities of the White Helmets, the civil defense volunteers famous for digging casualties from rubble.

As if to test the proposition that the international community has just as little concern for its own reputation as it does for the lives of Syrian civilians—nearly half of whom have been displaced from their homes nationwide—Russia apparently chose, on September 19, the seventh day of the ceasefire, to bomb the first aid convoy en route to rebel-held Aleppo. That decision will be remembered as a fateful one.

Russia and Syria were following a timeworn blueprint: Use force to kill and starve civilians, then lie brazenly to avoid responsibility. In this case, the evidence is too clear and the trespass too toxic to let pass. So far, we’ve seen a sharp turn in rhetoric from the UN and Washington. Sooner or later, whether in the twilight of the Obama administration or in the dawn of his successor’s, we will see a much harder “reset” in Western relations with Russia.

For years, voices from Syria have raised the alarm. After years of dithering, even some members of the international community had the decency to follow suit, like Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. “The country is already a gigantic, devastated graveyard,” al Hussein said this summer, warning Syria’s belligerents that sieges and intentional starvation campaigns amount to war crimes. “Even if they have become so brutalized [that] they do not care about the innocent women, children, and men whose lives are in their hands, they should bear in mind that one day there will be a reckoning for all these crimes.”

Belatedly, Western leaders are joining the chorus. UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon, who avoided taking a stand during years of violence against humanitarian organizations by the Assad regime, now publicly accuses Syria and Russia of war crimes. On September 30, the one-year anniversary of Russia’s direct entry into the war, Gareth Bayley, Britain’s Special Representative to Syria, issued a broadside. “From Russia’s first airstrikes in Syria, it has hit civilian areas and increasingly used indiscriminate weapons, including cluster and incendiary munitions. Its campaign has dramatically increased violence and prolonged the suffering of hundreds of thousands of civilians,” he said, blaming Russia for at least 2,700 civilian deaths. “Russia has proved to be either unwilling or unable to influence Assad and must bear its responsibility for the Assad regime’s atrocities.

America’s top diplomats, too, rail against Russia futilely. In a recently leaked recording of a meeting between a ham-handed but apparently sincere U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and members of the Syrian opposition, Kerry admitted that he lost the internal debate in the administration for greater intervention, more protection of civilians, and a stiffer stand against Russia’s triumphalist expansionism. But like a good soldier, he has continued to flog a bad policy, pushing perhaps much too hard on the small constituency of opposition Syrians who remain committed to a pluralistic, unified, democratic Syria.

Perhaps Russia has been searching for the West’s actual red lines all along, exploring how far it could go in Syria without provoking any push back from the United States and its allies. Maybe it finally found them after it bombed the UN aid convoy in September. Only time will tell if the recent pitched rhetoric translates into action.

One of the few consistent goals of U.S. policy in Syria over the last year was to shift the burden of responsibility for the crisis, or even guilt, to Russia. Throughout long negotiations, Washington has bent over backwards to act in good faith, trusting against all evidence that Russia was willing to act in concert to push Syria toward a political settlement. America’s leaders today appear shocked that Russia was acting as a spoiler, a fact clear to most observers long ago.

With the latest agreement in ashes—literally—and an ebullient Russia convinced it will encounter no blowback for its war crimes, America has a political chit in its hands. For now, Russia thinks it can achieve its strategic goals by relentlessly destabilizing the international order and lying as gleefully and willfully as the Assad regime. The United States helped underwrite that international order when the UN came into being in 1945, laying down moral markers on atrocities like genocide and war crimes, and crafting a web of interlocking institutions that increased global security and prosperity. As its primary enforcer, the United States also has been its primary beneficiary.

Now that Russia, determined to reestablish its status after the humiliating collapse of the Soviet Union, has pushed the United States into a humiliating corner and weakened that international order, it is raising the stakes. Either the United States will push back, or the disequilibrium will spread even further. In either case, many thousands more Syrians will perish. As Bassam Hajji Mustafa, a spokesman for the Nour al-Din al-Zinki Movement, one of the more effective, if violent, rebel militias influential around Aleppo, put it, “People have adapted to death, so scaring them with this siege is not going to work.” Those who remain in Aleppo echo this refrain again and again: The last holdouts have stayed out of conviction. It’s hard to imagine anything but death driving them out. “If Aleppo falls and the world stays silent, then that will be the end of the revolution,” Hajji Mustafa said.

In the end, Aleppo is not a story about the West; it is a cornerstone of Syria and an engine of wealth and culture for the entire Levant. Aleppo is the story of the willful destruction of a pivotal Arab state, a center of gravity in a tumultuous region in sore need of anchors. It’s a story of entirely avoidable human misery: the murder of babies, the destruction of homes, the dismantling of a powerful industrial and craft economy.

The institutions of global governance are under strain and international comity is frayed; as yet, however, none of the steps toward dissolution are irreversible. Such shifts take place over decades, not months. But the crisis in Syria presents the most acute test yet, and demands of the United States an active, robust, and strategic response that reinforces its commitment to the architecture of global governance—a system threatened by spoiler powers like Russia and ideological attacks from nativists, the right-wing fringe, and other domestic extremists in the West.

Ignoring its responsibilities in Syria—and opening the door for Russia to pound away at the foundations of the international order—hurts not only Syrians but the entire world. Perhaps, finally, Assad and his backers have gone far enough to provoke an American defense of that indispensable order that America helped construct.

Around Aleppo it’s not peace — just a break

[Originally published at TCF.org.]

REYHANLI, Turkey—Peace in Syria might appear less remote today than it has in recent years, but rebel commanders on the ground—like Colonel Hassan Rajoub, commander of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) Division 16—aren’t betting on it.

Col. Rajoub is taking advantage of the current lull to do what he thinks is wisest: stockpile weapons and plead with American and other foreign officers to provide enough support to resist a triple threat facing the FSA.

“We are at a very dangerous crossroads,” Rajoub said in an interview in Rehanli, the Turkish border town that serves as rear area for most of the rebel groups that openly take military support from the “Friends of Syria,” an alliance that includes the United States, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia.

Since a February 27 cessation of hostilities, Russia has suspended its major air offensive, although it could quickly resume if it chose. Talks are underway in Geneva between the Syrian government and an opposition delegation backed a number of rebel groups, but not all. Increasingly, it appears that the United States and Russia share a desire for a political transition that allows a more effective military campaign against ISIS.

According to rebels in the Turkish border zone, weapons have flowed steadily into Syria since the ceasefire began. Even those who hope for a political settlement aren’t betting on one any time soon. Instead they’re stockpiling for the next round, which they expect will be as desperate as the last. Although U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov say they want a transition by the summer, none of the rebel commanders in northern Syria expect a political settlement before 2017.

Up close, however, to commanders like Rajoub interviewed in mid-March during an extension of the ceasefire, the patchwork of diplomatic developments looks less like momentum toward a settlement and more like a timeout.

Aleppo’s state of play underscores just how difficult it would be to work out the details of a lasting settlement. It has proven impossible, even with massive Russian support, for the Syrian government to fully encircle the rebels in Western Aleppo. It isn’t known whether Russia made a tactical decision not to allow a full government takeover of Aleppo, in order to prevent government overreach, or whether it wasn’t able to. Moreover, despite indications that the Syrian civil war might be tilting toward a punishing stalemate, the factions around Aleppo—once the economic and industrial hub of Syria—have plenty of fight still left in them. During the ceasefire, skirmishes have continued over city’s strategic choke points. Militias have shifted their forces in anticipation of major battles they expect as soon as the ceasefire breaks down. And commanders with access to foreign arms, like Rajoub and his FSA colleagues, are shopping across the border in Turkey.

“We ask the Friends of Syria and they give us,” Rajoub said with a smile. “They have just now given us new supplies of everything. But we want some special weapons to give us a little bit of leverage.”

In the past, FSA commanders ritualistically complain that the United States won’t let them have high-tech missiles (man-portable air-defense systems, or MANPADS) that would enable them to shoot down government bombers and helicopters. But during interviews this with nearly a dozen FSA commanders, none of them lingered on the issue of MANPADS.

Instead, several FSA commanders said the United States had been forthcoming during the ceasefire period, replenishing arms stocks and leaving open the possibility that some anti-aircraft missiles might be released into northern Syria.

“We expect a surprise,” said one satisfied commander.

Another commander, who runs the operations room in Aleppo that coordinates among all the factions, nationalist and Islamist, fighting in the city, said that the February bombardment had driven many insurgent militias into retreat, but they had re-infiltrated most of their important positions since the ceasefire.

“We still are counting on the supporting nations, and we emphasize the United States because it is the ‘indispensable nation,’” said the commander, who goes by the sobriquet Abu Ahmed al Amaliat (which loosely translated means “Ahmed’s father, the operations guy”).

A complex web of combatants with very divergent agendas is competing for Aleppo. The FSA battalions, nationalist in orientation and allied with the Friends of Syria, wants Bashar al Assad gone but strongly favors a unified post-war Syria that preserves the institutions of state.

Hard line jihadists, including the Al Qaeda affiliate Nusra Front and ISIS, are not party to the ceasefire and are trying to establish their extreme version of Islamist governance in areas under their control. They can be distinguished from all other rebel groups because of their practice of takfiri jihad, through which they declare other groups apostate and then believe they are justified under religious law in using any tactic against them, no matter how nihilistic.

Kurdish forces have fought effectively against ISIS, and have at times collaborated with the United States, Russia, and the Syrian government, but they hope for an autonomous Kurdish region—a position anathema to all the other factions, which oppose federalism and support a unitary state.

The government wants to reconquer the entire city, and has employed its own forces, and has drawn as well on support from Iran and Russia, along with militia fighters from Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan.

There are also wild cards, such as the powerful Islamist rebel faction Ahrar el Sham, which has nationalist and jihadi constituents but hasn’t yet decided whether to break decisively in favor of an alliance with the FSA or with Nusra.

The government side of Aleppo is still home to an estimated 1.5 million people. The population on the rebel side has dwindled to about 300,000 living under horrific conditions: near constant bombardment, and shortages of everything. Rebel Aleppo can only be reached by one route, the Castello road, which is sandwiched between government forces on one side and jihadists on the other. Rebel-held Aleppo has lived in fear of a total siege for more than a year. Aleppo residents have watched the regime employ a siege-and-surrender tactic against places such as Eastern Ghouta and Madaya, where starvation has become common.

Opposition administrators are stockpiling food, fuel, and medicine, and working feverishly to unify their political and military leadership, but opposition leaders say that the decisive development won’t occur in Geneva but on the battlefields of Syria.

Rajoub said he planned to request fifty tons of explosives that night at meeting with with foreign officers at the Military Operations Center, or MOC. He said that fifteen nations have officers stationed in the MOC; they ask detailed questions about planned operations and demand thorough accounting for the weapons distributed. Rajoub had prepared satellite photographs of his area of operations with overlays showing his positions, enemy positions, and planned operations, which he displayed on his smartphone. His division is fighting around Aleppo, and if the government of Bashar al-Assad managed to reunite the divided city, it would mark a decisive turning point.

“The U.S. military commanders are always with us,” Rajoub said. “We ask. They are very cooperative. They understand our needs.”

He said he still fantasizes about MANPADS, but figured that the FSA could turn back its opponents without them.

In the midst of a continuing meltdown, it striking that plenty of actors, as angry as they are about a perception of American indifference, still welcome American help: activists, humanitarians, and military commanders arrayed against Bashar al Assad’s cynical dictatorship—which we ought to remember, played the most pivotal role in abetting ISIS and continues to devote resources to smashing nationalists while leaving ISIS, for the most part, untouched.

A close look at the Battle for Aleppo suggests it is far from won, and that progress on the ground, or stalemate, is ultimately what will determine the stance of the delegations in Geneva. Russia and the United States are trying to shape a military balance on the ground that will encourage their local allies and proxies to accede to a Moscow-Washington deal. But contested battlegrounds with so many factions are notoriously hard to shape, especially when many of the militias are fighting for their own neighborhoods and villages, or for what they view as a matter of ethnic or sectarian survival.

The budding superpower diplomacy, and even the tentative talks at Geneva, give cause for hope. But the military machinations around Aleppo should temper any unbridled optimism. In a destructive round-robin, where so many sides have lost so much, it’s a surprise how many still think they can win outright.

A plan to rebuild Syria no matter who wins war

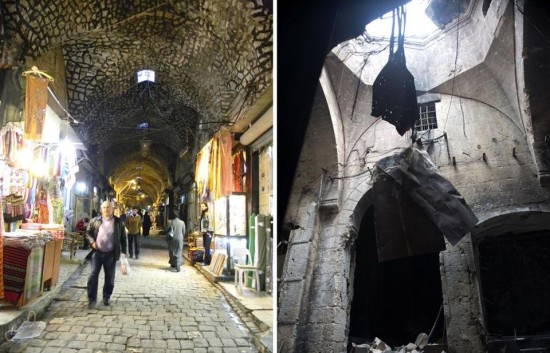

The souk in Aleppo, before and after its destruction in 2012. LEFT: WIKICOMMONS; RIGHT: MIGUEL MEDINA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

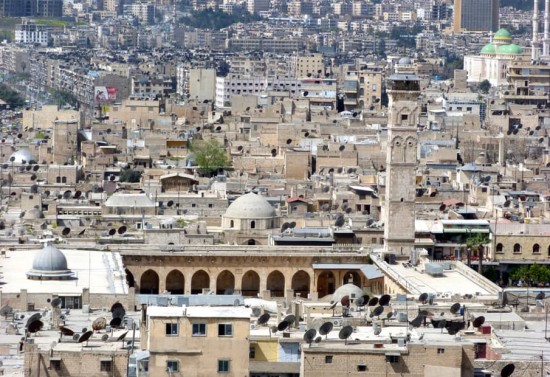

BEIRUT—The first year of Syria’s uprising, 2011, largely spared Aleppo, the country’s economic engine, largest city, and home of its most prized heritage sites. Fighting engulfed Aleppo in 2012 and has never let up since, making the city a symbol of the civil war’s grinding destruction. Rebels captured the eastern side of the city while the government held the west. The regime dropped conventional munitions and then barrel bombs on the rebels, who fought back with rockets and mortars. In 2012, the historical Ottoman covered souk was destroyed. In 2013, shelling destroyed the storied minaret of the 11th-century Ummayid Mosque. Apartment blocks were reduced to rubble. More than 3 million residents fled, out of a prewar population of 5 million. Today, residents say the city is virtually uninhabitable; most who remain have nowhere else to go.

In terms of sheer devastation, Syria today is worse off than Germany at the end of World War II. Bashar Assad’s regime and the original nationalist opposition are locked in combat with each other and also with a third axis, the powerful jihadist current led by the Islamic State. And yet, even as the fighting continues, a movement is brewing among planners, activists and bureaucrats—some still in Aleppo, others in Damascus, Turkey, and Lebanon—to prepare, right now, for the reconstruction effort that will come whenever peace finally arrives.

In downtown Beirut, a day’s drive from the worst of the war zone, a team of Syrians is undertaking an experiment without precedent. In a glass tower belonging to the United Nations’ Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, a project called the National Agenda for the Future of Syria has brought together teams of engineers, architects, water experts, conservationists, and development experts to grapple with seemingly impossible technical problems. How many years will it take to remove the unexploded bombs and rubble and then restore basic water, sewerage, and power? How many tons of cement and liters of water will be needed to replace destroyed infrastructure? How many cranes? Where could the 3 million displaced Aleppans be temporarily housed during the years or decades it might take to restore their city? And beneath all these technical questions they face a deeper one, as old as urban warfare itself: How do you bring a destroyed city back to life?

Critics dismiss the ongoing planning effort as a premature boondoggle, keeping technocrats busy creating blueprints that will have to be revised when fighting finally ebbs. But Thierry Grandin, a consultant for the World Monuments Fund who has worked and lived in Aleppo since the 1980s and is currently involved in reconstruction planning, disagrees. “It is good to do the planning now, because on day one we will be ready,” Grandin says. “It might come in a year, it might come in 20, but eventually there will be a day one. Our job is to prepare.”

The team planning the country’s future is a diverse one. Some are employed by the government of Syria, others by the rebels’ rival provisional government. Still others work for the UN, private construction companies, or nongovernmental organizations involved in conservation, like the World Monuments Fund. The Future of Syria project aims to serve as a clearinghouse, and to create a master menu of postwar planning options. As the group’s members outline a path toward renewal, they’re considering everything from corruption and constitutional reform to power grids, antiquities, and health care systems.

The task they have before them beggars comprehension. Across Syria, more than one-third of the population is displaced. Aleppo is in tatters, its center completely destroyed. The population exodus has claimed most of the city’s craftsmen, medical personnel, academics, and industrialists.

A modern country has been unmade during four years of conflict, and nowhere is the toll more apparent than in once-alluring Aleppo. But after horrifying conflict, countless places have found a way to return to functionality. What’s new in Syria is the attempt to come up with a neutral plan while the conflict is still in train. And Aleppo, the country’s historic urban jewel, will be the central test.

TO FIND A SIMILAR example of planning during wartime before the outcome was known, you have to go back to World War II. Allied forces spent years preparing for the physical, economic, and political reconstruction of Germany and Japan even before they could be sure who would win. Today, Americans tend mostly to recall the symbolic reconstruction after the war: the Nuremberg trials and the Marshall Plan, a colossal foreign aid program.

But undergirding those triumphs was the vast logistical operation of erecting new cities. It took decades to clear the moonscapes of rubble and to rebuild, in famous targets like Dresden and Hiroshima but in countless other places as well, from Coventry to Nanking. Some places never recovered their vitality.

Since then, a litany of divided and devastated cities has been left by other conflicts. Even those that eventually regained a sense of normalcy, like Beirut, Sarajevo, or Grozny, generally survived rather than thrived. Only a few countries—East Timor, Angola, Rwanda—offer what Syrian planners call “glimmers of hope,” as places that suffered terrible man-made disasters and then bounced back.

Of course, Syrian planners cannot help but pay attention to the model closest to home: Beirut, a city almost synonymous with civil war and flawed reconstruction. The planners and technocrats in the UN ESCWA tower overlook a gleamingly restored but vacant downtown from behind a veritable moat of blast barriers and sealed roads. Shell-pocked abandoned buildings stand as evidence of the tangled ownership disputes that have held back reconstruction a full quarter-century after the Lebanese civil war.

“We don’t want to end up like Beirut,” one of the Syrian planners says, referring to the physical problems but also to a postwar process in which militia leaders turned to corrupt reconstruction ventures as a new source of funds and power. He spoke anonymously; the Future of Syria team, which is led by a former Syrian deputy prime minister named Abdallah Al Dardari, doesn’t give on-the-record briefings. Since their top priority is to maintain buy-in from Syrians on all sides, they try to avoid naming names so as not to dissuade people they hope will use their plans when the war ends.

Syria’s national recovery will depend in large part on whether its industrial powerhouse Aleppo can bounce back. Until 2011, Aleppo had been celebrated for millenniums for its beauty and commerce. The citadel overlooking the center is a world heritage site. The old city and its covered market were vibrant, functioning exemplars of Islamic and Ottoman architecture, surrounded by the wide leafy avenues of the modern city. Aleppan traders plied their wares in Turkey, Iraq, the Levant, and all the way south to the Arabian peninsula. The city’s workshops, famed above all for their fine textiles, export millions of dollars’ worth of goods every week even now, and the economy has expanded to include modern industry as well.

Today, however, the city’s water and power supply are under the control of the Islamic State. Entire neighborhoods have collapsed under regime bombing and shelling: government buildings, hospitals, landmark hotels, schools, prisons. Aleppo is split between a regime side with vestiges of basic services, and a mostly depopulated rebel-controlled zone, into which the Islamic State and the Al Qaeda-affiliated Nusra Front have made inroads over the last year. A river of rubble marks the no-man’s land separating the two sides. The only way to cross is to leave the city, follow a wide arc, and reenter from the far side.

For now, said an architect who works for the rebel government in Aleppo under the pseudonym Tamer el Halaby, today’s business is simply survival, like digging 20 makeshift wells that fulfill minimal water needs. (He prefers not to have his real name published for fear that the government might target relatives on the other side of Aleppo.) Parts of the old city won’t be inhabitable for years, he told me by Skype, because the ground has literally shifted as a result of bombing and shelling.

“It will take a long time and cost a lot of money for this city to work again,” he said.

CLOSE TO A THOUSAND Syrians have consulted on the Future of Syria project, which comprises at least two ambitious initiatives rolled into one. The first and more obvious is creating realistic options to fix the country after the war—in some cases literal plans for building infrastructure systems and positioning construction equipment, in other cases guidelines for shaping governance.

At the Future of Syria, hospital administrators, civil engineers, and traffic coordinators each work on their given fields. They’re familiar with global “best practices,” but also with how things work in Syria, so they’re not going to propose pie-in-the-sky ideas. These planners also understand that who wins the construction contracts will depend on who wins the war. If some version of the current regime remains in charge, it will probably direct massive contracts toward patrons in Russia, China, or Iran. The opposition, by contrast, would lean toward firms from the West, Turkey, and the Gulf.

“Who will have the influence in Syria after the conflict? That will dictate who is involved in redevelopment. It all depends on who ends up being in political control,” says Richard J. Cook, a longtime UN official who supervised postconflict construction in Palestinian refugee camps and now works for one of the Middle East’s largest construction conglomerates, Dar Al-Handasah Consultants (Shair and Partners). Along with other companies, Dar Al-Handasah has offered its lessons learned from Lebanon’s reconstruction process to Syrian planners, and plans to compete to work in postwar Syria.

That leads to the second, more subtle, innovation of the Future of Syria project. For its plans to matter, they need to be politically viable no matter who is governing. So the planners have worked hard to persuade experts from all factions to contribute to the 57 different sectoral studies, hoping to come up with feasible rebuilding options that would be considered by a future Syrian authority of any stripe. Today, nearly 200 experts work full time for the project.

At the current level of destruction, the project planners estimate the reconstruction will cost at least $100 billion. Regardless of how it’s financed—loans, foreign aid, bonds—that’s a financial bonanza for whoever controls the reconstruction process. Some would-be peacemakers have suggested that reconstruction plans could even be used as enticements. If opposition militants and regime constituents think they’ll make more money rebuilding than fighting, they might have a Machiavellian incentive to make peace.

Underlying the details—mapping destroyed blocks, surveying the condition of the citadel, studying sewers—are bigger philosophical questions. How can a destroyed city be rebuilt, when the combination of people, economy, and buildings can never be reconstituted? Can you use reconstruction to undo the human damage of sectarianism and conflict? Recently a panel of architects and heritage experts from Sweden, Bosnia, Syria, and Lebanon convened in Beirut to discuss lessons for Syria’s reconstruction—one of the many distinct initiatives parallel to the Future of Syria project.

“You should never rebuild the way it was,” said Arna Mackic, an architect from Mostar. That Bosnian city was divided during the 1990s civil war into Muslim and Catholic sides, destroying the city center and the famous Stari Most bridge over the Neretva River. “The war changes us. You should show that in rebuilding.”

In the case of Mostar, the UN agency UNESCO reconstructed the bridge and built a restored central zone where Muslims and Catholics were supposed to create a harmonious new postwar culture. Instead, Mackik says, the sectarian communities keep to their own enclaves. Bereft of any common symbols, the city took a poll to figure out what kind of statue to erect in the city center. All the local figures were too polarizing. In the end they settled on a gold-colored statue of the martial arts star Bruce Lee.

“It belongs to no one,” Mackic says. “What does Bruce Lee mean to me?”

Despite such pitfalls, one area of potential for the planning process—and eventually for the reconstruction of Aleppo—is that it could offer the city’s people a form of participatory democracy that has so far eluded the Syrian regime and sadly, the opposition as well. People consulted about the shape of their reconstituted neighborhoods or roads will have been offered a slice of citizenship alien to most top-down Syrian leadership.

“You are being democratic without the consequences of all the hullabaloo of formal democratization,” says one of the Syrian planners who has contributed to the Future of Syria project and spoke on condition of anonymity.

What is certain is that putting Syria back together again is likely to be as least as expensive as imploding it. A great deal of money has been invested in Syria’s destruction— by the regime, the local parties to the conflict, and many foreign powers. A great deal of money will be made in the aftermath, in a reconstruction project that stands to dwarf anything seen since after World War II.

How that recovery is designed will help determine whether Syria returns to business as usual, sowing the seeds for a reprise of the same conflict—or whether reconstruction allows the kind of lasting change that the resolution of war itself might not.