Four years after Tahrir, what would make another uprising?

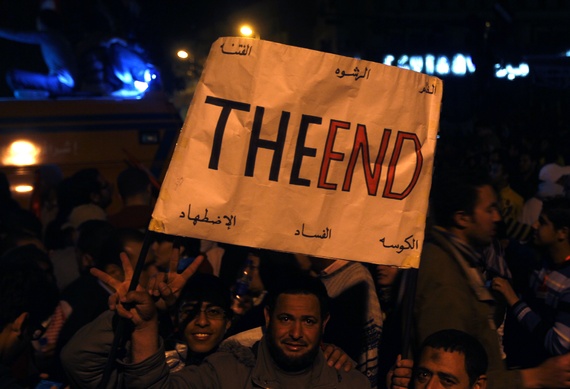

An anti-Mubarak protester in Tahrir Square, in November 2014 (Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters)

[Published in The Atlantic. Arabic translation available at Sasa Post.]

CAIRO—Four years after the revolution he helped lead, Basem Kamel has noticeably scaled back his ambitions. The regime he and his friends thought they overthrew after storming Tahrir Square has returned. In the face of relentless pressure and violence from the authorities, most of the revolutionary movements have been sidelined or snuffed out.

Egypt’s new strongman, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has injected new zeal and energy into the military establishment. He has established his rule using unprecedented amounts of force, including mass arrests and death sentences, and the elimination of freedoms that existed even under previous dictatorships. But he has also won considerable popularity, leading Egypt’s revolutionaries to seek new routes to change.

“Maybe in 12 years we will be back in the game,” Kamel told me during the January Coptic Christmas holidays, wearing a sweatsuit as he shuttled his kids to after-school sports. After some thought, the 45-year-old architect, who lives in southern Cairo, added a caveat: “Unless Sisi changes the rules.”

There’s been a dramatic downsizing of expectations since Sisi came to power in a military coup in July 2013 (he retired from the military and was elected president without any meaningful challenger in May 2014). But if the mood is grim among the activists who so recently turned Egypt’s power structure on its head, historical trends suggest that the victorious military establishment has plenty to worry about as well.

Sisi is younger, sharper, and more vigorous than Hosni Mubarak, but he’s applying the same tools to the same problems. A small, insular group of men makes all important decisions, from drafting the country’s new parliamentary-election law to managing the economy to deciding how to prosecute political prisoners. Foreign aid is a key pillar of support for the government. The main difference is in the faces around the top. Whereas Mubarak’s cabal included some rich civilians, Sisi relies almost exclusively on military men.

The problems are daunting no matter who leads Egypt. Unemployment is endemic. The nation can’t grow enough crops to feed itself, is running low on foreign currency, and runs up hefty bills importing energy and grain that it sells at heavily subsidized prices. There is no longer a free media in Egypt, and a regressive new law makes it almost impossible for independent NGOs to do their work. Political parties that don’t pay fealty to Sisi’s order are hounded and persecuted. One result of this repression is that there is no scrutiny of government policy, no new sources of ideas, and not even symbolic accountability for corruption, incompetence, and bad government decisions.

Egypt’s new ruler has made some shrewd moves. He has tweaked the food-subsidy system to reduce waste and corruption in bakeries, introducing a card system with points that allows consumers to spend their allowance on a variety of goods rather than lining up for bread that they end up throwing away. He paid a Christmas visit to the Coptic Cathedral in Cairo, the first time any Egyptian leader has done so since Gamal Abdel Nasser, reassuring some Christians after decades of increased marginalization of and violence against the beleaguered minority.

But unless he miraculously resolves the country’s underlying economic plight—a product of the previous six decades of authoritarian rule, most of it dominated by the military—Egypt will snap again sooner or later.

“Six months ago there was huge popular happiness with Sisi’s performance. Now already it is less,” said Ahmed Imam, a spokesman for Strong Egypt, one of the few active political opposition parties left in the country. “I believe in another six months you will find rage, and the rage will become public.”

* * *

The simplest way to understand the January 25, 2011 uprising against Mubarak’s military rule is as a rejection of a government that was both abusive and incompetent. Since the military coup that ended the monarchy and brought Nasser to power in 1952, Egyptian authoritarians have fared well enough when they provided tangible quality-of-life improvements, or when they leavened the disappointment of growing poverty with an increased margin of freedom. But by the end of his three decades in power, Mubarak provided neither: His corrupt government gutted services and the treasury, while his unaccountable military and police establishment freely meted out torture, arbitrary detention, and unfair trials.

According to his supporters and advisors, Sisi is gambling that he’ll pull off the kind of economic feats that characterized the apex periods of Egypt’s three major leaders in the modern era: Mubarak, Anwar Sadat, and Nasser.

So far, however, Sisi has needed to deploy draconian measures to keep control even at his moment of peak popularity. He has outlawed demonstrations. He has imprisoned tens of thousands, many for the simple offense of protesting. Old state security agents have returned to their old ways, humiliating dissidents by leaking their private phone calls to the media. Crackdowns target homosexuals, atheists, and blasphemers. Judges have sentenced to death hundreds of Muslim Brothers—until recently, members of an elected civilian ruling party—in shotgun trials that lasted a day or two and have made a mockery of Egypt’s once-respected judiciary. An activist from the secular April 6 Youth Movement recently had three years tacked on to his sentence because he dared ask about a Facebook page where the judge in his case had openly identified with Sisi’s regime and denigrated the revolutionaries, casting aside any pretense of judicial impartiality.

Such hardline tactics could reflect a military confidently in charge; many activists who subscribe to this view have chosen exile or a hiatus from public life. But the tactics also could reflect desperation: The old regime has won a reprieve, but it has to work much harder than before to keep a tenuous grip on power. In that case, the overwhelming chorus of support for Sisi could be just the prelude to another period of bitter disappointment and revolt.

Critical human-rights monitors continue to track government abuses, some from within Egypt despite the constant risk of arrest. A few youth and political movements continue to operate as well. The Revolutionary Socialists, the Youth Movement for Freedom and Justice, and April 6 all continue to organize, albeit on a modest scale; gone are the mass protests of 2011-2013. The Constitution Party, which includes some leading secular liberals, has been outspoken in its criticism of military rule. So has the Strong Egypt party, led by a former presidential contender and ex-Muslim Brother named Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, who has the distinction of having equally opposed abuses by Islamist and secular military regimes since Mubarak.

“Either the regime is reformed and resumes a democratic course, or its bad performance will provoke a revolution that will explode in its face,” Aboul Fotouh said in a recent interview in his home in a Cairo suburb. His party might run parliamentary candidates in the elections scheduled for March and April, but state security agents have made it impossible for the party to operate normally, canceling all 27 conference-room reservations it has made in the last three months—a favorite tactic resuscitated from Mubarak’s time.

* * *

Most of the leaders of the original uprising are in prison or exile. Some have been silenced, and some like, Kamel, seem willing to accept military repression as the necessary price for getting rid of the Muslim Brotherhood, which they considered the bigger threat. “Even knowing what I know today, I would say the Brotherhood is worse,” Kamel said.

Today, private and state media channels have become no-go zones for dissenting voices. Independent presenters like Yosri Fouda and comedian Bassem Youssef have gone off the air, and other one-time revolutionaries like Ibrahim Eissa have become shrill advocates for the regime.

In the four years that I’ve been reporting closely on Egypt’s transition from revolution to restoration, I’ve seen young activists go from stunned to euphoric to traumatized and sometimes defeated. I’ve seen stalwarts of the old regime go from arrogant and complacent to frightened and unsure to bullying and triumphalist. And yet, so far, the core grievances that drew frustrated Egyptians to Tahrir Square in the first place remain unaddressed. Police operate with complete impunity and disrespect for citizens, routinely using torture. Courts are whimsical, uneven, at times absurdly unjust and capricious. The military controls a state within a state, removed from any oversight or scrutiny, with authority over a vast portion of the national economy and Egypt’s public land. Poverty and unemployment continue to rise, while crises in housing, education, and health care have grown even worse than the most dire predictions of development experts. Corruption has largely gone unpunished, and Sisi has begun to roll back an initial wave of prosecutions against Mubarak, his sons, and his oligarchs.

Kamel has abandoned his revolutionary rhetoric of 2011 for a more modest platform of reform, working within the system. He was one of just four revolutionary youth who made it into the short-lived revolutionary parliament of 2012, and he helped found the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, one of the most promising new political parties after the fall of Mubarak.

He expects to run for parliament again with his party, but the odds are longer and the stakes lower. The parliament will have hardly any power under Sisi’s setup. Most of the seats are slated for “independents,” which in practice means well-funded establishment candidates run by the former ruling party network. The Muslim Brotherhood, the nation’s largest opposition group, is now illegal. Existing political parties can only compete for 20 percent of the seats, and most of them, like Kamel’s have dramatically tamed their criticisms.

“I think Sisi is in control of everything,” Kamel said. “Of course I am not with Sisi, but I am not against the state.”

That’s why he’s devoting his efforts to a training program for Social Democratic cadres, a sort of political science-and-organizing academy for activists and operatives that will take years to bear fruit. “It’s long-term work,” he said.

Still, something fundamental changed in January 2011, and no amount of state brutality can reverse it. Many people who before 2011 cowered or kept their ideas to themselves now feel unafraid.

“We want accountability, not miracles,” said Khaled Dawoud, spokesman for the Constitution Party. “We’re not asking for gay rights and legalized marijuana. We’re asking to stop torture in prisons.” Dawoud is a secular liberal activist who kept his integrity even during the period after Sisi’s coup when many of his peers cast their lot with the generals against the Islamists. He has been harassed by every faction, facing death threats and even a murder attempt by supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood.

In three years’ time, Egyptians took to the streets and saw three heads of state in a row flee from power: Mubarak, his successor Field Marshal Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, and President Mohammed Morsi. The legacies of the revolution are hotly contested, but one is indisputable: Large numbers of Egyptians believe they’re entitled to political rights and power. That remains a potent idea even if revolutionary forces and their aspiration for a more just and equitable order seem beaten for now.

In the worst of times under Mubarak, and before him Sadat and Nasser, mass arrests, executions, and the banning of political life kept the country quiet. But as Egypt heads toward the fourth anniversary of the January 25th uprisings, things are anything but quiet, despite the best efforts of Sisi’s state. Dissidents are smuggling letters out of jail. Muslim Brothers protest weekly for the restoration of civilian rule. Secular activists are working on detailed plans so that next time around, they’ll be able to present an alternative to the status-quo power. No one believes that this means another revolution is imminent, but the percolating dissatisfaction, and the ongoing work of political resistance, suggest that it won’t wait 30 years either.

“That’s our homework: to prepare a substitute,” said Mohamed Nabil, a leader in the April 6 movement who still speaks openly even though his group is now banned. “At the end Sisi is lying, and the Egyptian people will react. You never know when.”

Egypt’s Fractured Political Class Outgunned by Military

Protesters sing the national anthem as they rally against the dissolving of parliament, at the parliament building in Cairo June 19, 2012. (photo by REUTERS/Asmaa Waguih)

[Read the full story at Al-Monitor.]

From the Mediterranean coast to the desert plateau, Egypt is awash with rumors that have whipped the populace into a state of acute anxiety. Word has spread that a renewed state of emergency is imminent or that the Muslim Brothers plan to deploy a militia to the streets, that families should stock up on fuel or food because of “dark days ahead,” that a curfew will be imposed, that Hosni Mubarak’s death will delay a new president taking office or that last weekend’s election will have to be run again because of massive fraud.

The state of panic points to two sad trends: The military is consolidating power with increasing directness and public support, while the entire civilian political sphere has fractured to a degree that beggars the prospect of effective cooperation. Forget about unity in the face of a crusty military junta flush with victory. The moment for revolutionary system-change might well have passed for now. Instead, we can expect a period of retrenchment, nasty political infighting and polarization, all of which will benefit the authoritarians in charge.

No matter who is designated the winner this weekend (or in the eventuality that authorities indefinitely postpone a ruling on the disputed presidential race), the real victor will be the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF.

Meanwhile, the Muslim Brotherhood, whose candidate decisively won the presidential race by its own count, has promised not to resort to force if the unaccountable electoral authority awards the election to the ex-regime’s candidate, who has promised a “surprise.”

Either way, the next president will take office in the shadow of the ruling SCAF, which has boldly written itself into a position of dominance with a series of arbitrary court decisions and a temporary constitution that extends the military’s control almost indefinitely.

Primary responsibility for all of this mess rests with the military, which introduced a process designed to enervate the public through confusion, uncertainty and a long, constantly shifting timetable. Since Mubarak stepped down, the military has been in complete control. Lest people forget, it is the military that massacred peaceful protesters at Maspero in October 2011, and the military that is responsible for a state media that has peddled noxious sectarian propaganda against the Brotherhood and a xenophobic smear campaign to undermine the revolutionary youth.

No matter the sins of the Muslim Brotherhood and the liberals since they were sworn in as members of parliament in January, it’s important to remember that only the military had the power to drive a political transition, perk up the flailing economy or provide respectable security on the streets. SCAF has failed on all counts.

Nonetheless, the Muslim Brotherhood behaved with reprehensible brittleness and triumphalism. In parliament, it coddled up to the military dictators, refraining from passing legislation to challenge SCAF powers and engaged in majoritarian overreach with its determination to ram through a constitutional convention dominated by Islamists, rather than one built on principles of consensus and universal representation.

And many liberals have chosen to see these freely elected Islamists as a greater threat than the military dictatorship that kills and beats demonstrators, imprisons activists, tries civilians before military courts and insists by fiat or rigged judicial ruling on undoing every single political development that curtails military power.

As Egyptians awaited the decision of the capricious Presidential Election Commission, already delayed to much alarm from Thursday to the weekend, I watched a liberal grandee hector a pair of young revolutionaries. Mohamed Ghonim is a widely respected urologist and polyglot who founded a renowned clinic in the provincial Nile Delta city of Mansoura. Late in the evening at the Books & Beans café bookstore, seated between a baby grand piano and the window, Ghonim wagged his finger at the young men roughly a quarter his age who have spent the last year toppling a dictator, protesting in the streets, and campaigning for the pro-revolution presidential candidates who together took a majority of the vote in the first round but were too fractured to make into the runoff.

“These guys have to learn history and focus on one issue, the constitution, without messing around,” Ghonim said. Ahmed Shafiq, a retired air force general who served as Mubarak’s final prime minister, has promised a restoration of a “state of law” if elected, and is tightly aligned with the worst elements of the old regime’s abuse of power.

Yet Ghonim — like many liberals — appeared unconcerned about a Shafiq victory, stolen or legitimate. He cited Marxist-Leninist theory: The nastier the regime, the greater the clarity and therefore the better for the “second wave of the revolution.” This sort of blithe insouciance about another round of dictatorial revanchism runs deep among liberals, and will serve to further divide and discredit them among both revolutionaries and Islamists.

The SCAF might be comfortable with a Muslim Brotherhood presidency. Their powers are well assured, and they’ll benefit from an Islamist scapegoat in the president’s chair whom they can blame for the coming failures of governance. But the old ruling party apparatus and the police have much more to fear. Under Muslim Brotherhood rule, stalwarts of the National Democratic Party could see their assets confiscated and their local patronage and control machines dismantled. Abusive and once-all-powerful police officials might face prison and certainly can expect to see themselves marginalized or fired from the Ministry of the Interior. For them, this election is an existential contest. Shafiq would save them; Mursi might smite them. Among their ranks they count many of the richest business owners in Egypt, along with the top judges on the Supreme Constitutional Court, who incidentally (and without possibility of appeal!) control the electoral process.

One final matter merits further thought. The entire political class has obsessed about the constitution. What position will it give Islam? Will it stipulate a presidential, parliamentary or hybrid system? The primacy accorded the constitution is puzzling. Of course, the institutions and principles stipulated in the state’s constitution are important, but they are far less determinative than power. Hosni Mubarak eviscerated the rule of law in Egypt despite a decent-enough constitution and theoretical legal framework. The state’s power and intent trump rules. Over the past year and a half, the SCAF has used constitutional declarations, supra-constitutional declarations, the state of emergency and electoral procedures to tie the country in knots. In Egypt today, the law is a joke, issued by generals whose legitimacy is conjured by an unsubstantiated claim of authority, along with the guns that back it up. The courts make a mockery of the law, giving credence to obscene, fabricated complaints against activists filed by ex-regime hacks, dismissing candidates and elected officials on technicalities, exonerating police who kill civilians and contemplating a case to dissolve the Muslim Brotherhood on another technicality.

In fact, the only groups that appear serious about respecting rules and laws are those who have been emasculated by their misuse: the Muslim Brotherhood and the liberal opposition.

The political class appears determined to bring a bunch of lawyers to a gunfight with the SCAF.

Sadly, the moment of revolution has receded and the prospect of serious reform, while still possible, seems at a minimum years away. The malignant malfeasance of Egypt’s security state will continue unabated until it is forced to concede power. Only once the military’s power is stripped and it is sidelined from a transition should elected representatives concentrate their efforts on a new legal blueprint for the state.

Citizens can begin this process by refusing the legitimacy of any decision that comes from the SCAF. The dissolved parliament could meet in Tahrir Square under open air and issue its own constitution and laws. The fairly elected president could convene his cabinet in a café. Revolutionaries could hold sit-ins in government buildings, or better still, on the sidewalks in poor neighborhoods where they could explain their agenda to the wider public.

All this, however, would require a unity of purpose that has escaped a political class in thrall to the narcissism of minor differences, riven by class and sectarian prejudice, and led by craven politicians fatally tempted by the tiny slivers of power tossed to them by the SCAF. Until this mindset changes, we can expect the military to reign smugly over a rebellious but fragmented Egypt.

Inside Egypt’s Military Mind

CAIRO, Egypt — Retired Egyptian Army General Hosam Sowilam knows how to control a conversation. With a jocular smile and a booming voice, he’ll hold and repeat a phrase — “Chaos! Chaos! Chaos!” — until he’s drowned out the question he doesn’t care to answer, dispelling even the shadow of doubt as he regains the floor.

“What happened on January 25?” Sowilam bellowed by way of introducing his history of the uprising in Tahrir Square. “Many of our youths went to Serbia and the United States of America, where they received training in how to overthrow the regime. They received training from Freedom House, and funding from the Jewish millionaire Soros.”

He goes on to weave a detailed story of a foreign plot against Egypt, in which unscrupulous agents from America, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, backed by a web of corporate interests, took advantage of Egyptians legitimately dissatisfied about Hosni Mubarak’s plan to transfer power to his son.

“Look!” he says, pointing in a bond dossier at a page of logos from companies like Edelman and CBS. “All these corporations were behind the Arab spring. This is very dangerous.” There are headlines about Soros from websites like truthistreason.net and AnarchitexT.org (“I don’t know any thing about them,” Sowilam says. “I found them on the internet.”) Other data comes from better-known sources like The Washington Post and Wikileaks. He has carefully translated key points into Arabic to share with Egyptian reporters.

Although Sowilam holds no official role in the army that governs Egypt today, he considers that army his life, and relishes any chance to speak for its values and mindset, if not its official policies. He remains close to senior officers, and had a second career after the military at a defense think tank and now as an unofficial spokesman for the military. (I first met him a year ago while reporting a story about the military’s view on then-President Mubarak’s succession plans; Sowilam adamantly criticized the notion of hereditary power, but also warned that the military never would permit Islamists to rule Egypt.)

Bald and squat, with a body shaped like a calzone, Sowilam has the typical build of an artilleryman. An early career surrounded by the thud of big guns marred his hearing, which is why he often shouts in casual conversation. Born in 1937, Sowilam came of age and attended the military academy in the 1950s, in the halcyon era of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Free Officers revolt. He took his commission when the army was at the zenith of its power, boldly refashioning Egypt’s political and economic order. He fought in the humiliating defeat of 1967, which he directly attributed to the Free Officers’ “disastrous experiment” with running the country. He later served abroad, including a stint as military attaché in India.