Is Anyone Ready to Actually Lead Egypt?

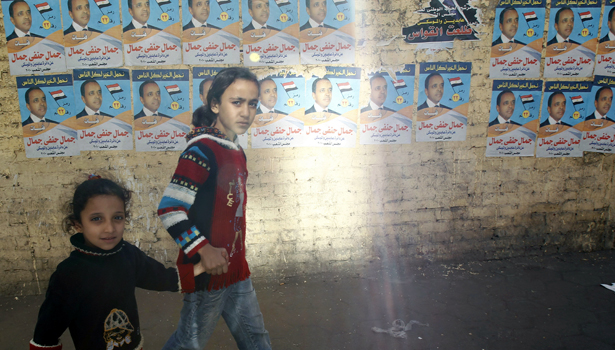

Girls walk past Muslim Brotherhood campaign posters in Cairo. (Reuters)

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

The Muslim Brotherhood is inflexible and exclusive, the military power-hungry and self-interested, liberals are in disarray, and a country that badly needs cooperation is once again plagued by division.

CAIRO, Egypt — The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi appears to have won Egypt’s first contested presidential election in history, a mind-boggling reversal for the underground Islamist organization whose leaders are more familiar with the inside of prisons than parliament. Whether or not Morsi is certified as the winner on Thursday — and there is every possibility that loose-cannon judges will award the race to Mubarak’s man, retired General Ahmed Shafiq — the struggle has clearly moved into a new phase that pits political forces against a military determined to remain above the government.

The ultimate battle, between revolution and revanchism, will remain the same whether Morsi or Shafiq is the next president. It’s going to be a mismatched struggle, one that will require unity of purpose, organization, and the sort of political muscle-flexing that has escaped civilian politicians for the entire 18-month transition process. If they can’t marshal a strong front on behalf of a unified agenda, they are likely to fail to wrestle the most important powers out of the military’s stranglehold.

After a year and a half in direct control, Egypt’s ruling council of generals (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF) appears to have grown fond of its power. As the presidential vote was being counted, SCAF issued a new temporary constitution that gives it almost unlimited powers, far greater than those of the president. It can effectively veto the process of drafting the new permanent constitution, and it retains the power to declare war.

“We want a little more trust in us,” a SCAF general said in a surreal press conference on Monday. “Stop all the criticisms that we are a state within a state. Please. Stop.”

In fact, all the military’s moves, right up to the last-minute dissolution of parliament and the 11th-hour publication of its extended, near-supreme powers, give Egyptians every reason to distrust it. Sadly, the alternatives are not much more reassuring.

Shafiq, the old regime’s choice, mobilized the former ruling party with an unapologetic, fear-driven campaign, drumming up terror of an Islamic reign while promising a full restoration to Mubarak’s machine. If he ends up in the presidential palace, he could place the secular revolutionaries and the Muslim Brotherhood in harmony for the first time since the early days of Tahrir Square.

Morsi, meanwhile, is known as an organization enforcer, not as a gifted politician or negotiator — which are the skills most in need as Egypt embarks on its high-risk struggle to push aside a military dictatorship determined to remain the power behind the throne.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate has few assets in his corner. He represents the single best-organized opposition group but doesn’t control it. Revolutionary and liberal forces are in disarray. Mistrust, even hatred, of the Muslim Brotherhood has flared among groups that should be the Brotherhood’s natural allies against the SCAF. And the Brotherhood itself has wavered between cutting deals with the military and confronting it when the military changes the terms. Many secular liberals say they relish the idea of the dictatorial military and the authoritarian Islamists fighting each other to exhaustion.

All this division promises a chaotic and difficult transition for Egypt after 18 months of direct military rule. If officials honor the apparent results (an open question, since the elections authority is run by SCAF cronies), Morsi will head an emasculated, civilian power center in the government that will have little more than moral suasion and the bully pulpit with which to face down the SCAF.

While the military’s legal coup overshadows the election results, it doesn’t render them meaningless. The presidency carries enormous authority; managed successfully, it’s the one institution that could begin to counter and undo the military’s evisceration of law and political life.

The example of parliament is instructive. Some observers said from the beginning that a parliament under SCAF would have no real power. But that didn’t turn out to be the problem with the Islamist-controlled parliament. It had symbolic power, and it could pass laws even if the SCAF then vetoed them. What made the parliament a failure was its actual record. It didn’t pass any inspiring or imaginative laws, it repeatedly squashed pluralism within its ranks, and it regularly did SCAF’s bidding. That’s what discredited the Brotherhood and its Salafi allies and led to their dramatic, nearly 20 percent drop in popularity between the parliamentary elections and the first round of presidential balloting five months later.

It would be greatly satisfying if the corrupt, arrogant, and authoritarian machine of the old ruling party were turned back, despite what appears to have been hints of an old-fashioned vote-buying campaign and a slick fear-mongering media push, backed by state newspapers and television. On election day, landowners in Sharqiya province told me the Shafiq campaign was offering 50 Egyptian pounds, or about $8.60, per vote.

But it would be greatly unsatisfying for that victory to come in the form of a stiff and reactionary Muslim Brotherhood leader who appears constitutionally averse to coalition-building and whose political instincts seem narrowly partisan, at a time when Egypt’s political class is locked in death-match with the nation’s military dictators.

Egypt’s second transition could last, based on the current political calendar, anywhere from six months to four years. A new constitution will have to be written and approved, likely with heavy meddling from the military and with profound differences of philosophy separating the Islamist and secular political forces charged with drafting it. A new parliament will have to be elected. And then, possibly, the military (or secular liberals) could force another presidential election to give the transitional government a more permanent footing.

Meanwhile, during this turbulent period, Egypt will have to contend with the forces unleashed during the recent, bruising electoral fights.

Shafiq’s campaign brought into the open the sizable constituency of old regime supporters (maybe a fifth of the electorate, based on how they did in recent votes) and Christians terrified that their second-class status will be grossly eroded under Islamist rule.

Liberals will have to explain and atone for their stands on the election. Many of them said they would prefer the “clarity” of a Shafiq victory to a triumphalist Islamic regime under Morsi, and cheered when parliament was dissolved — appearing hypocritical, expedient, and excessively tolerant of military caprice.

The Brotherhood still hasn’t made a genuine-seeming effort to placate and include other revolutionaries, spurning entreaties to form a more inclusive coalition. It attempted, twice, to force through a constitution-writing assembly under its absolute control. Yet, once more, the Brotherhood has a chance to save itself. So far, at each such juncture it has chosen to pursue narrow organizational goals rather than a national agenda. It would be great for Egypt if the Brotherhood now learned from its mistakes, but precedent doesn’t suggest optimism.

Partisans of both presidential candidates told me they expected a big pay-off when their man won: cheaper fertilizer, free seeds, a flood of affordable housing, jobs for all their kids, better schools. None of these things is to be expected in the near future under any regime in Egypt. Disappointment is sure to proliferate as everyone realizes how difficult Egypt’s long slog will be.

There’s much hand wringing among Egyptians about the last-minute power grab by the military through the sweeping constitutional declaration it published on Sunday. In a land of made-up law and real power, why the obsession with power-mad generals, co-opted judges, and the arbitrary declarations they publish? SCAF’s decisions only matter because of its raw power, tied to the gunmen it has deployed on the streets and its willingness to use them against unarmed civilians. This inequity will only change with a shift in actual power, not because of a clever and just redrafting of laws. An elected president, or a defenestrated parliament for that matter, could issue its own, better constitution and declare it the law of the land, and enter a starting contest with SCAF. Authority belongs to whomever claims it and can make it stick.

Egypt’s Bumpy Road

WBUR’s Here & Now discussed the precarious mechanics of the transition in Egypt with me today. As the latest turns demonstrate, this is a process with no rules, or as I call them, “fake rules.” Shafiq is out! Shafiq is back. What next? There’s a very real, and destabilizing, possibility that some court declares the entire process invalid since it’s based on the dubious legal authority of the SCAF, and the constitutional declaration that materialized from whole cloth after the March referendum, which blessed a text that largely vanished. Listen to the conversation here.

Who Is Derailing Egypt’s Transition to Democracy?

Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood presidential candidate Khairat al-Shater, who was disqualified from his campaign. Reuters

[Originally published in The Atlantic.]

Many Egyptian liberals rejoiced at Tuesday’s news that three of the most polarizing — and popular — presidential candidates, including those representing the Muslim Brotherhood and the ultra-conservative Salafists, would not be allowed to compete. The final ruling from the Supreme Presidential Elections Commission followed a lower court decision a week earlier that disbanded the lopsided and widely detested constitutional convention, which had been forced through by the Muslim Brotherhood and its Salafi allies.

On the surface, the decisions about the presidential race and the constitutional convention both thwart some serious electoral shenanigans by the Muslim Brotherhood and others, but this is hardly progress for liberalism in Egypt. Unfortunately for Egypt’s prospects, both rulings came from opaque administrative bodies with questionable authority and motives. In the case of the presidential commission, there is no avenue for appeal. And in the potentially more important matter of the constitution, a decidedly political question was buried in a layer of obfuscating legalese.

No one in Egypt can explain the rules governing the two most important hinge points in Egypt’s pivot away from authoritarianism: the selection of the president and the drafting of the constitution.

Sadly, it augurs well for the ruling military junta and the increasingly bold coterie of reactionary forces in Egypt — and poorly for all the emerging political factions, from the secular revolutionaries to the most conservative Islamists.

It’s not just that liberal, short-term gains came through illiberal means. It’s that the pair of game-changing decisions call into question what forces, if any, have control over political life in Egypt.

Events are moving so fast that even seasoned Egyptian activists are still spinning. Presidential candidates put themselves forward on April 6. The frontrunners were all controversial: Hazem Salah Abou Ismail, a charismatic Salafi preacher who has criticized military rule but also embraced extreme, at times conspiratorial, political views and wants to implement Islamic law; Khairat Shater, the most powerful man in the Muslim Brotherhood, who broke his own promise that his group would not have a candidate; and Omar Suleiman, the Hosni Mubarak regime’s spy chief, who reversed himself at the last minute and entered the race with the active support of the reconstituted intelligence services.

The presidential election commission invalided ten candidates, including these three front-runners, on technicalities. Sheikh Hazem fell afoul of a rule that he originally supported, thinking it would hurt secular liberals; he was disqualified because his mother — like millions of Egyptians — had taken a second, in this case American, passport. Shater was banned because he served prison time under Mubarak’s rule; he had been convicted of fraud by a military court, almost certainly a fabricated case that was part of the ancien regime witch hunt against the Brotherhood. Suleiman, whose candidacy had caused the most alarm among liberals and Islamists alike, was kicked off the ballot because some of the petition signatures he collected were deemed fraudulent.

The first ruling technically was consistent with regulations, which themselves are a disturbing sign of the nationalist chauvinism ripening in Egypt. The second two sound like trumped-up technicalities, even if their immediate impact is to calm Egypt by removing divisive candidates from the race. Suleiman’s exit is undeniably good for Egypt, but there was a more legitimate process underway in parliament to exclude his candidacy on the merits, because of his prior role as Mubarak’s henchman and vice president. Alleging forged signatures was a signature old regime trick to discredit opponents such as Ayman Nour after he challenged Mubarak for the presidency in 2005.

In Shater’s case, the military regime had issued a pardon for the trumped-up old conviction. One vestige of the old regime, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, gave Shater the green light; another carryover, the elections bureaucracy, vetoed it.

Meanwhile, the constitution-writing farce ground to a halt last week, on April 10, when it was invalidated by the Supreme Administrative Court, a lower court subject to appeal. The Brotherhood and the Salafis had packed the Constituent Assembly with a veto-proof majority of its own members. According to its founding rules (which were dictatorially issued by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces last year), the constitutional committee was supposed to broadly represent Egyptian society. Instead, it was an Islamist monolith, alienating virtually every other imaginable constituency, from the establishment clerics of Al Azhar and the Coptic Church to women, workers, peasants, liberals, and nationalists. Egypt’s many constitutional and legal scholars were notably absent.

A boycott had already weakened the Assembly, which lost legitimacy with all but the staunchest supporters of the Brotherhood and the Salafi Noor Party. But it was dissolved on a technicality. According to the court, the Islamists in parliament aren’t allowed to appoint themselves to write the constitution. The court said the Brotherhood had broken the rules — which is odd, given that the Brotherhood had followed the constitutional process to the letter even while abnegating its spirit.

The ruling leaves the Brotherhood free to appoint another, equally imbalanced and illegitimate assembly, so long as its members are Islamists not already sitting in parliament. The fundamental problem remains — the Brotherhood is able, and appears willing, to behave in the same authoritarian manner as Mubarak’s regime.

What’s really going on here? Who decided to disqualify three presidential front-runners? Who shut down the constitutional process that had been convened, however poorly, by the freely and fairly elected parliament? On what grounds?

In both instances, a group of essentially anonymous and unaccountable bureaucrats radically transformed the political landscape, citing reasons at best opaque and at worst nonsensical, deploying jargon and legalese to set the parameters of Egypt’s future state.

We have no idea, really, who these officials are, whose interests they serve, whether they are acting in good faith, as independent decision-makers, or at someone else’s behest. It’s a replay of the way major decisions were made in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, with a charade of faceless government cogs announcing policies rooted in a complex hierarchy of laws while the all-powerful president claimed complete and impartial detachment.

This is what Issandr El Amrani at the Arabist calls “lawfare” in the Egyptian context, and it extends a nefarious precedent, cultivated during decades of dictatorship. From 1954 to 2011, civilians ruled Egypt under a nominally liberal constitution; in practice, those civilian presidents were retired generals who exercised absolute authority through the military and police, all the while ignoring the constitution on the pretext of a decades-long “state of emergency.”

Today it’s a different, more complicated story; there’s evidence that more players than the ruling military junta have a role in these behind-the-scenes decisions. The next two months are crucial. Presidential elections are to begin May 23 and conclude June 17. Field Marshal and acting president Mohamed Hussein Tantawi suggested this week that a constitution must be written in a hurry, before a new chief executive takes over at the end of June. Procedurally, that’s a near-impossibility. A year and a half of posturing and maneuvering will play out in this final stage, when the old and new power players in Egypt will fight for control of the next phase.

The way this election and constitution-writing process is playing out will at best cast a pall over the transition and, at worst, presage a return to outright authoritarian military rule.

The Lost Dream of Egyptian Pluralism

[Originally published in The Boston Globe, subscribers only.]

CAIRO — It might have seemed naïve to an outsider, but one of the great hopes among the revolutionaries who humiliated Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak more than a year ago was that the country’s strongman regime would finally yield to a democratic variety of voices. Both Islamic revolutionaries and secular liberals spoke up for modern ideas of pluralism, tolerance, and minority rights. Tahrir Square was supposed to turn the page on a half-century or more of one-party rule, and open the door to something new not just for Egypt, but for the Arab world: a genuine diversity of opinion about how a nation should govern itself.![]()

“We disagree about many things, but that is the point,” one of the protest organizers, Moaz Abdelkareem, said in February 2011, the week that Mubarak quit. “We come from many backgrounds. We can work together to dismantle the old regime and make a new Egypt.”

A year later, it is still far from clear what that new Egypt will look like. The country awaits a new constitution, and although a competitively elected parliament sat in January for the first time in contemporary Egyptian history, it is still subordinate to a secretive military regime. Like all transitions, the struggle against Egyptian authoritarianism has been messy and complex. But for those who hoped that Egypt would emerge as a beacon of tolerant, or at least diverse, politics in the Arab world, there has been one big disappointment: It’s safe to say that one early casualty of the struggle has been that spirit of pluralism.

“I do not trust the military. I do not trust the Muslim Brothers,” Abdelkareem says in an interview a year later. In the past year, he helped establish the Egyptian Current, a small liberal party that wants to bring direct democracy to Egyptian government. Despite his inclusive principles, he’s urged the dismissal from public life of major political constituencies with whom he disagrees: former regime supporters, many Islamists, old-line liberals, and supporters of the military. He shrugs: “It’s necessary, if we’re going to change.”

He’s not the only one who has left the ideal of pluralism behind. A survey of the major players in Egyptian politics yields a list of people and groups who have worked harder to shut down their opponents than to engage them. The Muslim Brotherhood — the Islamist party that is the oldest opposition group in Egypt, and the one with by far the most popular support — has run roughshod over its rivals, hoarding almost every significant procedural power in the legislature and cutting a series of exclusive deals with the ruling generals. Secular liberals, for their part, have suggested that an outright coup by secular officers would be better than a plural democracy that ended up empowering bearded fundamentalists who disagree with them.

When pressed, most will still say they want Egypt to be the birthplace of a new kind of Arab political culture — one in which differences are respected, minorities have rights, and dissent is protected. However, their behavior suggests that Egypt might have trouble escaping the more repressive patterns of its past.

***

IN A COUNTRY that had long barred any meaningful politics at all, Tahrir’s leaderless revolution begat a brief but golden moment of political pluralism. Activists across the spectrum agreed to disagree — this, it was widely believed, was the very practice that would lead Egypt from dictatorship to democracy. During the first month of maneuvering after Mubarak resigned in February 2011, Muslim Brotherhood leaders vowed to restrain their quest for political power; socialists and liberals emphasized due process and fair elections. The revolution took special pride in its unity, inclusiveness, and plethora of leaders: It included representatives of every part of society, and aspired to exclude nobody.

“Our first priority is to start rebuilding Egypt, cooperating with all groups of people: Muslims and Christians, men and women, all the political parties,” the Muslim Brotherhood’s most powerful leader, Khairat Al-Shater, told me in an interview last March, a year ago. “The first thing is to start political life in the right, democratic way.”

Within a month, however, that commitment had begun to fray. Jostling factions were quick to question the motives and patriotism of their rivals, as might be expected from political movements trying to position themselves in an unfolding power struggle. More surprising, and more dangerous, has been the tendency of important groups to seek the silencing or outright disenfranchisement of competitors.

The military sponsored a constitutional referendum in March 2011 that supposedly laid out a path to transfer power to an elected, civilian government, but which depended on provisions poorly understood by Egyptian voters. The Islamists sided with the military, helping the referendum win 77 percent of the votes, and leaving secular liberal parties feeling tricked and overpowered. The real winner turned out to be the ruling generals, who took the win as an endorsement of their primacy over all political factions. The military promptly began rewriting the rules of the transition process.

With the army now the country’s uncontested power, some leading liberal political parties entered negotiations with the generals over the summer to secure one of their primary goals — a secular state — in a most illiberal manner: a deal with the army that would preempt any future constitution written by a democratically selected assembly.

The Muslim Brotherhood responded by branding the liberals traitors and scrapping its conciliatory rhetoric. The Islamists, with huge popular support, abandoned their initial promise of political restraint and instead moved to contest all seats and seek a dominant position in the post-Mubarak order. The Brotherhood now holds 46 percent of the seats in parliament, and with the ultra-Islamist Salafists holding another 24 percent, the Brotherhood effectively controls enough of the body to shut down debate. Within the Brotherhood, Khairat Al-Shater has led a ruthless purge of members who sought internal transparency and democracy — and is now considered a front-runner to be Egypt’s next prime minister.

The army generals in charge, meanwhile, have been using state media to demonize secular democracy activists and street protesters as paid foreign agents, bent on destroying Egyptian society in the service of Israel, the United States, and other bogeymen.

Since the parliament opened deliberations in January, the rupture has been on full and sordid display. The military has sought legal censure against a liberal member of parliament, Zyad Elelaimy, because he criticized army rule. State prosecutors have gone after liberals and Islamists who have voiced controversial political positions. Islamists and military supporters have also filed lawsuits against liberal politicians and human rights activists, while the military-appointed government has mounted a legal and public relations campaign against civil society groups.

***

THE CENTRAL QUESTION for Egypt’s future is whether these increasingly intolerant tactics mean that the country’s next leaders will govern just as repressively as its last. Scholars of political transition caution that for states shedding authoritarian regimes, it can take years or decades to assess the outcome. Still, there are some hallmarks of successful transitions that Egypt appears to lack. States do better if they have an existing tradition of political dissent or pluralism to fall back on, or strong state institutions independent of the political leadership. Egypt has neither.

“Transitions are always messy, and the Egyptian one is particularly messy,” said Habib Nassar, a lawyer who directs the Middle East and North Africa program at the International Center for Transitional Justice in New York. “To be honest, I’m not sure I see any prospects of improvement for the short term. You are transitioning from dictatorship to majority rule in a country that never experienced real democracy before.”

Outside the parliament’s early sessions in January, liberal demonstrators chanted that the Muslim Brotherhood members were illegitimate “traitors.” In response, paramilitary-style Brotherhood supporters formed a human cordon that kept protesters from getting close enough to the parliament building to even be heard by their representatives.

At a rally for the revolution’s one-year anniversary in Tahrir Square, Muslim Brotherhood leaders preached and made speeches from a high stage to celebrate their triumph. It was unclear whether they were referring to the revolution, or to their party’s dominance at the polls. It was too much for the secular activists. “This is a revolution, not a party,” some chanted. “Leave, traitors, the square is ours not yours,” sang others.

Hundreds of burly brothers linked arms, while a leader with a microphone seemed to taunt the crowd. “You can’t make us leave,” he said. “We are the real revolution.” In response, outraged members of the secular audience tore apart the Brotherhood’s sound system and pelted the stage with water bottles, corn cobs, rocks, even shards of glass.

The Arab world is watching closely to see what happens in the next several months, when Egypt will write a new constitution and elect a president in a truly competitive ballot, and the military will cede power, at least formally. Even in the worst-case scenario, it’s worth remembering that Egypt’s next government will be radically more representative than Mubarak’s Pharaonic police state.

Sadly, though, political discourse over the last year has devolved into something that looks more like a brawl than a negotiation. If it continues, the constitution drafting process could end up more ugly than inspiring. The shape of the new order will emerge from a struggle among the Islamists, the secular liberals, and the military — all of whom, it now appears, remain hostage to the culture of the regime they worked so hard to overthrow.