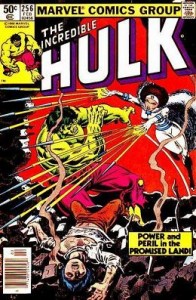

Hulk in the the Holy Land

My friend Brian Katulis has written perhaps the most penetrating short meditation on Israel-Palestine published in quite some time — a historical look at the long conflict through the eyes of the pre-Oslo Incredible Hulk.

My friend Brian Katulis has written perhaps the most penetrating short meditation on Israel-Palestine published in quite some time — a historical look at the long conflict through the eyes of the pre-Oslo Incredible Hulk.

In “Power and Peril in the Promised Land,” Bruce Banner stows away on a ship and wakes up in Israel, where he befriends a young Arab boy who is killed by Arab terrorists. This angers Bruce, who turns into the Incredible Hulk and takes the boy’s body next door to Jordan, all the while chased by the Israeli super heroine Sabra.

One can imagine Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, George Mitchell or even President Obama sympathizing with the Hulk’s frustration found on the last page: “Boy died because boy’s people and yours both want to own land! Boy died because you wouldn’t share.”

Priceless. And timeless.

Justice deferred, or deterred?

In Lebanon, crises unfold in unbearably slow motion until a sudden, usually deadly, climax. Everyone tunes out except for the participants and the hardened, usually professional, Lebanon-watchers; it’s all tedious process until somebody gets hurt.

In Lebanon, crises unfold in unbearably slow motion until a sudden, usually deadly, climax. Everyone tunes out except for the participants and the hardened, usually professional, Lebanon-watchers; it’s all tedious process until somebody gets hurt.

That’s what happened on Tuesday when Hezbollah forced a government collapse. It sounds dramatic, and it’s a critical point in the slow boiling showdown that’s simmered for years over the International Special Tribunal on the Lebanon assassinations. Hezbollah toppling the government is just an incremental step, although a major one, in the process by which Hezbollah will try to fatally cripple the Tribunal and render Hariri incapable of governing.

Saad Hariri inherited the premiership five years after his father was murdered. In a measure of the molasses pace of Lebanese politics, it took Hariri five months to negotiate a coalition cabinet; that government barely lasted 14 months.

There are only a few viable ways for this to turn out.

1. Hariri could fully repudiate the Tribunal, withdraw Lebanese support for it, and let it die on the vine. Even if Hezbollah members are indicted, nothing will come of it. This outcome, I think, is unlikely, only because it leaves Hariri with nothing – no actual power, and no legitimacy.

2. Hariri could insist on supporting the Tribunal. Hezbollah would be forced to escalate, and might eventually use violence as it did in May 2008, when it briefly conquered West Beirut. In this case, the Tribunal would be scuttled as well, but Hariri would preserve integrity and therefore political legitimacy. In an op-ed in today’s New York Times, I argue that Hariri is most likely to pursue this course.

3. Lebanon could limp on under a caretaker government for a year or two (like it did for long stretches in 2007 and 2008), unable to cooperate with the Tribunal, scuttle it, or make any controversial decisions. This is also a very likely scenario, as David Kenner writes at Foreign Policy.

4. Hezbollah could manage to form a government with a pro-Resistance prime minister, a scenario that would probably quickly spark a war with Israel, as Juan Cole points out today.

5. Hezbollah could decide to throw some bones to the Tribunal, under pressure from Syria and/or Iran. This outcome is the least likely; there doesn’t seem to be any pressure coming from Hezbollah’s patrons to moderate in the showdown over the assassinations, in all likelihood because neither state would benefit from a full accounting of the string of murders in Lebanon that began with the Hariri killing. The entire Axis of Resistance benefits from a confrontation that strengthens Hezbollah, weakens a government allied to Saudi Arabia and the United States, and which blames Israel for all the killings in Lebanon in a scenario that stretches credulity for all audiences except the partisans of Hezbollah.

The only scenario we’re unlikely to see is one is the “full justice option”: the International Tribunal releases compelling evidence about the assassinations of Rafik Hariri and all the other anti-Syrian figures murdered since 2005; the most important suspects are arrested and put on trial; and the powerful entities with stakes in Lebanon honor the judicial process and accept its outcome. That scenario is only a dream.

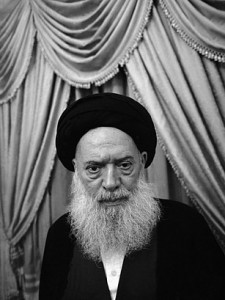

Fadlallah remembered

Just surfaced on the web, this remembrance that I wrote for Time magazine’s annual farewells issue:

Ayatullah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah survived an apparent CIA assassination attempt — a 1985 car bombing in Beirut that killed 80 people — and wore the attempt on his life as a badge of honor. The fiery cleric, whose most famous fatwa blessed suicide bombers in the war against Israel, was an intellectual pioneer of militant Islam: a brilliant jurist and tireless organizer, reviled by Washington as the spiritual leader of Hizballah.

But by the time of his death (of natural causes), Fadlallah had broken with Hizballah and the toxic legacy of his early edicts. He criticized Iran’s clerical rule, supported women’s rights and insisted on dialogue with the West. When I interviewed him, he was a soft-spoken and gracious host who enjoyed debating policy and philosophy. His passing marks a step backward for reform in the combustible world of Islamist militancy.

No Big Deal

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

The great international problems of our time beggar the imagination: global warming, pandemics, war crimes, nuclear proliferation, just to name a few. Their complexity confounds the most agile of technocrats, and the stakes involved are high, affecting billions of people living under every sort of government.

For half a century, the conventional approach to these problems has been to build massive international treaties. Intricate worldwide problems demand an integrated approach — a grand bargain, so to speak, that addresses all the winners and losers in a single, encompassing agreement.

This is the animating assumption behind the world’s approach to global warming, for example. To persuade growing nations like China to limit their consumption of fossil fuels, the thinking goes, the world needs a comprehensive framework ensuring that more developed nations make equivalent sacrifices. The climate is simply too large a problem to address piecemeal, or by tinkering with minor symptoms.

But what if this approach results in less progress? What if more modest agreements — on climate change, loose nukes, and other sweeping problems — would yield better results than a long, noble quest for a grand bargain?

From the Archives

I was cleaning out my office ahead of the New Year, and I found the press badge that the US military issued me in Kuwait in 2003. Just a few weeks before the invasion of Iraq, the military press office (known during that phase of the war as the CFLCC PAO) accredited more than a thousand journalists. Lots were embedding for the invasion, but plenty more of us were operating on our own. We still needed badges to deal with the ubiquitous military.

The spokesman’s office organized sessions to plan how to bring unembedded journalists to the site of the WMD he expected to be discovered. In other ways, too, the flacks were planning ahead for a long slog in Iraq: my accreditation lasted more than a year, through May 2004.

The terminology, though, still makes me laugh — the unwitting sense of humor of the acronym-happy bureaucrats who brought us hits like the quickly discarded “Operation Iraqi Liberation.” America was suffering global recriminations for eschewing allies and multilateral institutions in its march to war. With no apparent trace of irony the military’s public affairs department borrowed the term being flung at the US government by angry critics, and applied it to the reporters who had chosen not to embed: we were “unilateral journalists.” To this day it’s my favorite title I’ve ever earned.

WBUR’s Here & Now

Robin Young brought me into the studio on Tuesday to talk about my column in The Boston Globe about “engagement hawks,” the pragmatists who argue that America needs a more coherent strategy to deal with terrorist-designated groups and other enemies.

Talk to Terrorists

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

Ronald Reagan framed the debate over whether to talk to terrorists in terms that still dominate the debate today. “America will never make concessions to terrorists. To do so would only invite more terrorism,” Reagan said in 1985. “Once we head down that path there would be no end to it, no end to the suffering of innocent people, no end to the bloody ransom all civilized nations must pay.”

America, officially at least, doesn’t negotiate with terrorists: a blanket ban driven by moral outrage and enshrined in United States policy. Most government officials are prohibited from meeting with members of groups on the State Department’s foreign terrorist organization list. Intelligence operatives are discouraged from direct contact with terrorists, even for the purpose of gathering information.

President Clinton was roundly attacked when diplomats met with the Taliban in the 1990s. President George W. Bush was accused of appeasement when his administration approached Sunni insurgents in Iraq. Enraged detractors invoked Munich and ridiculed presidential candidate Barack Obama when he said he would meet Iran and other American adversaries “without preconditions.” The only proper time to talk to terrorists is after they’ve been destroyed, this thinking goes; any retreat from the maximalist position will cost America dearly.

Now, however, an increasingly assertive group of “engagement hawks” — a group of professional diplomats, military officers, and academics — is arguing that a mindless, macho refusal to engage might be causing as much harm as terrorism itself. Brushing off dialogue with killers might look tough, they say, but it is dangerously naive, and betrays an alarming ignorance of how, historically, intractable conflicts have actually been resolved. And today, after a decade of war against stateless terrorists that has claimed thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of foreign lives, and cost trillions of dollars, it’s all the more important that we choose the most effective methods over the ones that play on easy emotions.

Long Form Best of 2010

I’m quite honored to find my memoir of the Iraq invasion in At Length on the top 20 list for this year at longform.org. They’ve chosen quite a line-up of pieces, including a bunch I have not yet read but have just put in my Instapaper.

I’m quite honored to find my memoir of the Iraq invasion in At Length on the top 20 list for this year at longform.org. They’ve chosen quite a line-up of pieces, including a bunch I have not yet read but have just put in my Instapaper.

Larry Kaplow on Iraq

One of my favorite voices on Iraq is Larry Kaplow, the veteran reporter who to my knowledge spent more time in Baghdad than any other Western reporter. He has weighed in today with the kind of droll summation that is his trademark.

“It’s not over yet,” on Foreign Policy, describes the biggest fault lines splitting Iraq and threatening disaster as potently in the Mesopotamian war’s eighth year as it they did in its first. That’s right; Iraq’s quieter, but it’s still at war, as Larry reminds us in his “let’s cut the BS” fashion.

Larry is a tireless reporter and a good friend (we lived a few doors apart in the Hamra hotel for the couple of years I spent in Baghdad). At the height of the sectarian killing in Iraq, Larry liked to remind people that calling the conflict a civil war misleadingly implied that sectarian militias were fighting one another, when in fact, most of the violence entailed militias from one sect killing civilians from another.

Larry was well ensconced in Baghdad months before the American invasion began in March 2003, and he stayed, more or less without interruption, until the fall of 2009. He returned this summer and helped produce one of the most humane (and perversely enjoyable) accounts of what’s happened in Iraq for This American Life. The hour-long show is well worth streaming online or downloading to your iDevice.

On both Foreign Policy and This American Life, Larry is reminding us of the horrifying and still-uncalculated human toll of the Iraq war – and that despite the recent spells of quiet, he’s warning us that there’s still reason to fear.

If War Comes, Indeed

More than a month after skimming it, I have had the time to carefully read Jeffrey White’s paper on what a new war between Hezbollah and Israel might look like. “If War Comes: Israel vs. Hizballah and Its Allies,” a Washington Institute for Near East Policy publication, contains reams of useful information about the military tactics that parties to another Lebanon war might employ. However, White builds his argument on some misunderstandings and highly debatable assumptions about actors other than Israel. His analysis ignores much of the history of Israel’s last 30 years of war. And it fails to imagine any of the creative measures Hezbollah and its allies might take in another conflict.

More than a month after skimming it, I have had the time to carefully read Jeffrey White’s paper on what a new war between Hezbollah and Israel might look like. “If War Comes: Israel vs. Hizballah and Its Allies,” a Washington Institute for Near East Policy publication, contains reams of useful information about the military tactics that parties to another Lebanon war might employ. However, White builds his argument on some misunderstandings and highly debatable assumptions about actors other than Israel. His analysis ignores much of the history of Israel’s last 30 years of war. And it fails to imagine any of the creative measures Hezbollah and its allies might take in another conflict.

White’s main arguments are:

- Israel and Hezbollah both want a rematch from the inconclusive 2006 war.

- The next time around the stakes will be higher: both sides will fight for a decisive result.

- Hezbollah’s relationships with Syria and Iran make it more likely that a conflict will escalate into a regional conflagration.

- At its conclusion, White argues, a devastating Israel-Hezbollah war could create major new political crises, leave Israel occupying some of Lebanon and possibly all of Gaza, and destroy extensive civilian infrastructure – but he says it might also “break” Hezbollah military, weaken the Syrian regime, limit Iran’s influence, and weaken Hamas.

It’s definitely worth reading, and Andrew Exum posted his own very perceptive response to the paper on his blog. I want to amplify some similar questions and criticisms.

Fundamentally, White doesn’t account for the political reality of Lebanon today: Hezbollah has won the support of 1 million or more Lebanese, and achieved a statistical tie in the last elections. As a result, Hezbollah controls one-third of the government ministries, enjoys warm collegial relations with the president, the Lebanese Army, and much of the state’s institutions, and holds not only veto power but provides counsel to the weak government helmed by Saad Hariri.

Furthermore, Hezbollah has effectively silenced those forces in Lebanon that question Hezbollah’s right to manage its own militia, independent from the government’s army. Any attack by Israel on Lebanon – especially one that involveds widespread bombing of civilian infrastructure in particular in areas populated by Lebanese who oppose Hezbollah – will only renew Hezbollah’s legitimacy and expand its dominance over Lebanese politics.

There is simply no outcome of a war that, as White imagines, could leave Hezbollah “broken as a military factor in Lebanon and weakened politically.” (To “break” Hezbollah would require Iran and Syria to end their partnerships with it.) Hezbollah’s military prowess depends on a few thousand fighters and relatively low-tech armaments that Iran and Syria can resupply at little cost. Hezbollah’s staying power stems from the web of influence it has built with its militia, its politicians, its network of social and educational institutions, and its increasingly potent ideology of Islamic Resistance.

There is simply no outcome of a war that, as White imagines, could leave Hezbollah “broken as a military factor in Lebanon and weakened politically.” (To “break” Hezbollah would require Iran and Syria to end their partnerships with it.) Hezbollah’s military prowess depends on a few thousand fighters and relatively low-tech armaments that Iran and Syria can resupply at little cost. Hezbollah’s staying power stems from the web of influence it has built with its militia, its politicians, its network of social and educational institutions, and its increasingly potent ideology of Islamic Resistance.

In passing, White invokes other assumptions that at best raise enormous questions and problems:

- He suggests that after another war Israel will occupy part of Lebanon and perhaps all of Gaza. Israel’s troubling experience doing so in the past led it to unilaterally withdraw from Lebanon in 2000 and Gaza in 2006. What does White think has changed to make occupation of these areas more sustainable or effective for Israel?

- In 2006, Israel thought that holding all of Lebanon accountable for the behavior of Hezbollah would weaken Hezbollah and strengthen its opponents. The opposite happened, and Hezbollah emerged stronger than ever before. Why would the same course of action by Israel this time produce different political results?

- The case for an expanded war depends on a calculus that Hamas, Syria and Iran might be drawn into a war, directly, if they believe Hezbollah is losing. An alternate interpretation suggests that none of those actors would have an incentive to directly involve themselves in an Israel-Lebanon war, especially if they believe that Hezbollah wins politically no matter what the outcome on the battlefield. (In my estimation, a Hezbollah that resists and survives to fight again wins politically even if its military forces are decimated.) The behavior of the “Axis of Resistance” parties in Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009), the 2006 Lebanon war, and previous crises, suggests they see no need for overt involvement in a time of hot war in order to cash in on the political benefits of being allies afterward.

- What of Israel’s cost in diplomatic support and strained relations if it engages in the kind of speedy and widespread campaign White describes? “War on this scale may come as a chock to some of Israel’s supporters, and to countries and organizations under the spell of ‘proportionality,’” he writes. Indeed, such a war could cost Israel vital support domestically, and in the United States, not to mention bringing it approbation and possible legal action supported by parties “under the spell of ‘proportionality,’” like the United Nations and the United States, whose military hews to that principle in its own laws of war.

- Iran and Syria gain from Hezbollah’s willingness to fight Israel, and its presumed survival of such a conflict. They have little to gain from a frontal military confrontation with Israel, and would likely be content to sit on the sidelines, frustrating any attempt to expand a war and fulfill the almost Polyanna-ish hopes to “reorder” regional politics, critically weaken all of Israel’s enemies in a single war, and “shatter” Hezbollah’s “myth of resistance and military power.”

There are lots of other questions worth asking, including whether analysts should take Israel’s war in Gaza as a fair preview of a conflict with a major opponent like Hezbollah.

Andrew Exum very graciously questioned White’s assumptions in his response to the paper at WINEP in September, and pointed out that the entire exercise seems to concentrate on the minutia of military tactics at the expense of examining the overall political and strategic context.

The analysis betrays a common Achilles Heel I’ve encountered while reporting on the Middle East – a real lack of familiarity with the governments, militant movements, and public sentiments in Arab states and in Iran. Many Hezbollah supporters I interview read Haaretz on line, study Hebrew, and read books like Ariel Sharon’s autobiography. They might not understand Israel and Israeli society, but they try, and their attempts at self-education have translated into adaptive tactics and strategy. Meanwhile, supporters of Israel all too often forget to question their own assumptions, make critical assessments of Israel’s enemies, or update those assessments as those enemies evolve. As a result, they can fall into analytical traps, misapprehending the motives of their opponents, their levels of public support, and the likely political consequences of applying military force to them.

If I understand White correctly, he’s arguing that next time Israel goes to war on its northern border, Israel should apply lethal, overwhelming, widespread military force to Lebanon, and it should be prepared to simultaneously do so to Gaza, Syria, and Iran. Such a venture, White argues, would probably leave Israel in a stronger position.

Reality, and the experience of Israel’s last wars, suggests the opposite. Widespread conflict would probably not leave Israel more secure, and would at the same time unleash manifold waves of unintended consequences. As the United States learned from its venture in Iraq, upending the card table doesn’t necessarily lead to better hands in the next game.

Jeffrey White hasn’t provided any compelling reasons why Israel would emerge in dramatically better condition than it is in today after a massive war against Lebanon, Syria, Gaza and Iran, and he certainly hasn’t provided any evidence (historical, comparative, analytical) that war in 2011 would play out differently than it did for Israel in 2009, 2006, 2000, 1996, 1993, and 1982.

He has, however, given us a glimpse of the kind of pie-in-the-sky assumptions needed to convince an American audience that a high-risk, expeditionary, regional war might yield great, unspecified consequences – without accounting for the chilling risks such a war carries for millions of Arabs, Israelis, and for U.S. interests in the Middle East.

Broadway Debut

Last week I had my Broadway premier at the Cort Theatre. I expect it might also be my last appearance on a stage there. Josh Yaffa, an editor at Foreign Affairs, invited me for a “talkback” after the play Time Stands Still. The story chronicles two journalists, a photographer and a writer, who return to New York scarred from covering the conflict in Iraq. The play deals with two interlocking matters — the demise of a relationship and the personal toll of a journalist’s work in the crucible of a war zone.

Two hours of emotional theater about how one couple navigated their relationship and their coverage of the Iraq war sparked a confessional half-hour conversation. Anne Barnard and I moved to Iraq together in 2004, a year into covering the story, and made our first home there. We closed down The Boston Globe Baghdad Bureau in 2006, nearly a year after we married. Our story thankfully doesn’t parallel that of the protagonists of Time Stands Still, but the pressures that warped and ravaged their psyches and relationship felt very familiar.

Josh asked a lot of smart questions of me and the three cast members who joined us on stage, Laura Linney, Brian D’Arcy James and Eric Bogosian. In response to an audience question about embedded journalism, Josh talked about his trip this summer to Chechnya, “embedded” with Human Rights Watch, and he observed that most conflict zone reporting depends on somebody’s help. The real measure of the work depends on how well the journalist contextualizes her work and on who’s hosting the embed.

I’m still unsure of one issue we discussed: can an individual find a healthy balance between war reporting and family life? I can’t generalize about others, but for me almost all work-life balance is cyclical rather than integrated — meaning I alternate periods of frenetic work (or long assignments away from home) with periods of immersion in my family and home. That whiplash is all the more extreme when the work period is in a war zone; and I haven’t covered combat since my son was born in 2008.

The other issue worth mentioning is the question of a reporter’s responsibility. In the play, Laura Linney’s character, the driven photographer, struggles with guilt because she intrudes on the private grief of others. A supporting character also questions the photographer’s role as a bystander, chastising her for passively documenting when she could be actively involved in helping others. Guilt and ambivalence are certainly natural reactions to war, which can dole out suffering indiscriminately, especially if one is a foreign journalist whose presence is voluntary. However, I don’t know of any case in the last decade’s wars where journalists could have helped innocent victims of conflict and instead chose to stand by out of a sense of professional ethics. I’ve seen war photographers in Bint Jbail set down their cameras to carry civilians to ambulances. I’ve seen Western journalists, as well as their Middle Eastern colleagues, give money and major logistical help to sources, passers-by and colleagues. So the binary sense that a journalist has to choose between documentary distance or empathic involvement seems somewhat false.

As for the sense of shame at intruding in the personal grief of others: it’s a very human and very instinctive reaction to chronicling the pain of others. As storytellers with a public platform, though, we’re well aware that we’re not doing our work solely for the subjects of or victims in our tales; at times, we’re not doing it for them at all. The act of bearing witness can be motivated by solidarity, but it is not a collective social act. Sometimes, in war journalism, we’re telling stories for our audiences. If the reason for doing so is sufficiently compelling, then the discomfort or even cruelty of gathering the story is worth it.

Dick Gregory, in his autobiography, recalls the scene at murdered civil rights activist Medgar Evers’ funeral:

The press was there that day, and I remember the way everybody gasped a little when a photographer from Life magazine almost stood on Medgar’s coffin to get a picture of Mrs. Evers. I gasped, too, but when I saw that picture, that beautiful picture of a single tear running down Mrs. Evers’ face, I knew that photographer could have stood inside that coffin and it would have been all right. (p. 190)

A different type of war, but the same questions.

You can listen to the discussion at the Time Stands Still talkback here; scroll down to the third talkback on October 26.

Hezbollah’s Boy Scouts

Where can you learn how to brush your teeth well, tie a knot, articulately recite a Hassan Nasrallah speech, and if you’re lucky, how to join the war against Israel? The answer is the Mahdi Scouts, Hezbollah’s contribution to the international scouting movement. Drawing liberally on Western scout movements as well as the Iranian revolution, Hezbollah has put together a dynamic movement that effectively instills its ideology and tactics in the very young. The Mahdi Scouts showcase Hezbollah’s dual approach — building community through religion and at the same time, mobilizing their devotees through an appeal to fight a unifying enemy.

This extract from A Privilege to Die published today in Foreign Policy describes the day I spent with a Mahdi Scout troop in Khiam.

Mohammed Dawi, the sweaty and plump scout leader, met us at the entrance to Khiam town. He was a redhead with freckles, and looked more Irish than Lebanese. The younger scouts were waiting in the basement of a high school a mile or so from the prison. The troop leader led them in a chant of welcome. Most of them wore blue shirts with epaulets, white scarves, and oversized badges featuring a photograph of a scowling Ayatollah Khomeini. Two boys who looked about ten wore full military fatigues.

It seemed the day’s activities had been planned with my visit in mind. The children marched downstairs single file and broke up by age group. The “buds,” six or seven years old, assembled for a puppet show, emceed by a man in a worn panda suit who sang lines from Nasrallah’s speeches. The “sprouts,” eight to ten years old, sat around tables at the rear of the room drawing pictures, their ideas inspired by a chubby and soft-spoken young woman named Malak Sweid. She was a graphic design student and zealous party apparatchik.

In “guided drawing,” the kids drew pictures of Israelis weeping in defeat, denoted by Stars of David on their helmets, or of Israelis stepping on Lebanese. Other children, with evident direction by Malak, depicted crosses and crescents, symbolizing the Lebanese Christians and Muslims, chained by vicious Stars of David. Other pictures spoke less to the conflict with the Jews than to Islamic values. One child’s picture showed women in low-cut gowns holding martini glasses and cigarettes in old-fashioned holders. “Smoking Harms Your Health” was the title.

The Enemy Becomes You

I’d wondered for a long time about Hezbollah’s tree-planting program. Once when I spent the day with a Mahdi Scout troop the boys planted a bank of cypress trees as a windbreak by a Khiam playground, but I hadn’t encountered a lot of arboreal work.

I’d wondered for a long time about Hezbollah’s tree-planting program. Once when I spent the day with a Mahdi Scout troop the boys planted a bank of cypress trees as a windbreak by a Khiam playground, but I hadn’t encountered a lot of arboreal work.

In fact Hezbollah plants trees big time; Hassan Nasrallah appeared in public on Saturday for the first time in years to plant what the party claimed was its millionth sapling in the Dahieh, Beirut’s southern suburb. When it comes to symbolism (and institution-building), Hezbollah has openly borrowed from Israel and the early Zionist movement. Tree-planting and reforestation have been tremendously effective in Israel, both from a practical standpoint and as a way of cultivating popular attachment for the land. No simple is more apt (or as compelling, perhaps) as a little sapling taking root, firming up, and growing into a tree. It seemed like a no-brainer that Hezbollah would incorporate tree-planting into its tactical canon.

I first noticed the story reported by Alistair Lyon of Reuters, then quickly found links to the report on Hezbollah’s Al-Manar website, which broadcast the planting near Nasrallah’s house.

Jihad al Binaa, or the Holy Struggle for Reconstruction, spearheaded the urban tree-planting campaign over the last few months, Nasrallah said on Al-Manar:

“We wanted to plant this tree in this particular place, near our residence in Haret Heriek, which was destroyed during the 2006 war, to address every citizen and say: If every Lebanese plants a tree next to his house and pledged to take care and preserve it, imagine how our country would look like.”

Indeed. Lebanon could use more trees, and the congested confines of the unplanned, overcrowded Dahieh in particular could use anything to improve quality of life.

The Next War

How eager is Hezbollah for another conflict with Israel? On my last trip to Lebanon in September, I found both Hezbollah’s officials and the party’s rank and file feeling ready — bristling for a rematch, confident if not precisely eager. Hezbollah officials said they had doubled their fighting ranks (one said the number had tripled) since 2006. Supporters living in the border regions, like Aita al Shaab, said they had finally fully recovered from the last war and felt ready to fight again.

How eager is Hezbollah for another conflict with Israel? On my last trip to Lebanon in September, I found both Hezbollah’s officials and the party’s rank and file feeling ready — bristling for a rematch, confident if not precisely eager. Hezbollah officials said they had doubled their fighting ranks (one said the number had tripled) since 2006. Supporters living in the border regions, like Aita al Shaab, said they had finally fully recovered from the last war and felt ready to fight again.

Hezbollah supporters who time and again have lost their homes and livelihoods seem to embrace continued confrontation. What’s more, based on what they told me, they believe they’ll emerge at least as strong — politically and strategically — from another war as they did in 2006, even though nearly all of the people I interviewed thought the next conflict would be apocalyptic in its ferocity.

Lebanon has become even more polarized than it was in the years immediately after the 2006 war. Then the split worsened between those who support Hezbollah’s approach to Islamic Resistance and those who espouse a less confrontational course (and hold a majority in the government). There used to be a substantial pool of Lebanese in the middle; they wanted non-sectarian, non-confrontational politics for their country but who also sympathized with Hezbollah’s resistance project. By now, though, it seems that the soft middle has largely vanished. Most of the people I talked to were quite emphatic, either in their absolute loyalty to Hezbollah or in their absolute conviction that Hezbollah was ruining Lebanon.

I wrote about Hezbollah’s view of the coming conflict in today’s Times.

AITA AL SHAAB, Lebanon — It was from this shrub-ringed border town that Hezbollah instigated its war withIsrael in 2006, and supporters of the militant Shiite movement sound almost disappointed that they have not fought since.

“I was expecting the war this summer,” said Faris Jamil, a municipal official and small-business owner. “It’s late.” He has yet to finish rebuilding his three-story house, destroyed by an Israeli bomb that year.

In 2006, Hezbollah guerrillas crossed the border a few hundred yards from the town center, ambushed an Israeli patrol and retreated through Aita al Shaab with the bodies of two Israeli soldiers.

Hezbollah officials and supporters said they were now sending a pointed message to Israel through their efforts to rebuild, repopulate and rearm the south.

“We are not sleeping,” said Ali Fayyad, a Hezbollah official and member of Parliament. “We are working.” He receives visitors every weekend in a family home in Taibe, the site of a deadly tank battle in 2006.

Four years later, Hezbollah appears to be, if not bristling for a fight with Israel, then coolly prepared for one. It seems to be calculating either that an aggressive military posture might deter another war, as its own officials and Lebanese analysts say, or that a conflict, should it come, would on balance fortify its domestic political standing.

Pointless peace process?

Writing today in The Daily Beast, I ask why Washington appears to invest so much hope in the latest direct talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. People I talked to in the Middle East as these talks were getting underway were almost universally resigned in advance to failure on this round.

Writing today in The Daily Beast, I ask why Washington appears to invest so much hope in the latest direct talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. People I talked to in the Middle East as these talks were getting underway were almost universally resigned in advance to failure on this round.

Two suggestions diplomats and observers in the region made: bring actors like Hamas and the Israeli opposition into the talks, and change the structural incentives for Israel and Palestinian parties, which currently reward the status quo.

Not a single person I interviewed in the Middle East during the last two months expected anything to come of the current talks—certainly not anything good—although, for the record, no one predicted either that a failed peace process would unleash a new intifada or wholesale change in Israeli priorities.

Instead, the Arab diplomats, analysts, and activists who support Hamas and Hezbollah with whom I spoke seemed in accord that for the time being, neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians saw anything to gain from dialogue, except for earning chits with Washington.

The main benefit of a peace process, in this view, is that Washington wants one, and so long as it doesn’t cost anything, Washington’s allies in Ramallah and Jerusalem are happy to oblige.

Tribunal bedeviling Hezbollah

In the kind of notoriety that really excites a geek like me, my favorite blogger on Lebanon has interviewed me about A Privilege to Die. Qifa Nabki talked to me about what it is, exactly, that I’m writing and arguing about Hezbollah, and delves into some of his favorite topics – like Hezbollah’s influence on the wider Arab world and the social-ideological recipe that distinguishes Hezbollah from other mass-mobilization Islamist movements.

In the kind of notoriety that really excites a geek like me, my favorite blogger on Lebanon has interviewed me about A Privilege to Die. Qifa Nabki talked to me about what it is, exactly, that I’m writing and arguing about Hezbollah, and delves into some of his favorite topics – like Hezbollah’s influence on the wider Arab world and the social-ideological recipe that distinguishes Hezbollah from other mass-mobilization Islamist movements.

He asks how Hezbollah might respond if the International Special Tribunal investigating the 2005 murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri were to indict some Hezbollah members.

During my reporting trip to Lebanon in September I was surprised by Hezbollah’s uncompromising position on this issue. Party officials whom I interviewed echoed their leader Hassan Nasrallah’s absolutist stance: Hezbollah wouldn’t turn over any members, Hezbollah wouldn’t even recognize the Tribunal’s authority, and Hezbollah would ask the rest of the Lebanese government to adopt Hezbollah’s position.

If Hezbollah sticks to its guns on this issue, so to speak, it could quickly escalate into internal violence. During the crisis from 2006 to 2008, Hezbollah could argue that it was willing to negotiate so long as the other political parties in Lebanon were willing to give Hezbollah the one-third of power it was due demographically and by its share of seats in parliament. In the event of a Tribunal indictment of Hezbollah operatives, however, Hezbollah will find itself in a complicated position. If the indictment presents compelling evidence, Hezbollah will find its pure image substantially tarnished. And if Hezbollah is willing to withdraw from the government and go to war against it, rather than surrender any indicted members, it will risk alienating a broad segment of the Lebanese public that until now has supported Hezbollah’s Islamic resistance project, or at least, not stood in its way.

Sharing the Nile

Especially in the Middle East, there are always people uttering dark apocalyptic warnings about the coming water wars. Competition over scarce oil is nothing, the thinking goes, compared to what people and their governments will do when water starts running out.

Especially in the Middle East, there are always people uttering dark apocalyptic warnings about the coming water wars. Competition over scarce oil is nothing, the thinking goes, compared to what people and their governments will do when water starts running out.

Scarcity, of course, is nothing new, and “water wars” have already been happening for some time. They’re not cataclysmic (and usually not entirely binary) like wars over a specific piece of land, which either you control, or you don’t. Israel and Lebanon have fought over a contested border with at least one eye on the watersheds and rivers on both sides. Iraq, Syria and Turkey have had problems over the Tigris and Euphrates, the present result being that the two great rivers are muddy trickles by the time they reach southern Iraq. I imagine there are countless other examples.

Egypt is now contending with the end of its own era of water abundance. A colonial-era treaty gave Egypt and Sudan 80 percent of Nile’s water. The upstream African countries are now sufficiently stable — and eager for economic development — that they have challenged this arrangement. Negotiations collapsed and now Egypt has until next May to rejoin talks, or face a new regime designed by the upstream nations in the Nile watershed.

This isn’t the kind of conflict that I would expect to spark a traditional war, but it’s uncharted, and fascinating territory. You can read more in my story from this Sunday’s New York Times.

One place to begin to understand why this parched country has nearly ruptured relations with its upstream neighbors on the Nile is ankle-deep in mud in the cotton and maize fields of Mohammed Abdallah Sharkawi. The price he pays for the precious resource flooding his farm? Nothing.

“Thanks be to God,” Mr. Sharkawi said of the Nile River water. He raised his hands to the sky, then gestured toward a state functionary visiting his farm. “Everything is from God, and from the ministry.”

But perhaps not for much longer. Upstream countries, looking to right what they say are historic wrongs, have joined in an attempt to break Egypt and Sudan’s near-monopoly on the water, threatening a crisis that Egyptian experts said could, at its most extreme, lead to war.

“Not only is Egypt the gift of the Nile, this is a country that is almost completely dependent on Nile water resources,” said a spokesman for the Egyptian Foreign Ministry, Hossam Zaki. “We have a growing population and growing needs. There is no way we can accept this kind of threat.”

Egypt’s military II

Michael Hanna elaborates his views on the Egyptian military’s role in a presidential transition at Democracy Arsenal. He brings up some of the crucial Mubarak era history (which I didn’t have room for in my NYT piece on the subject), in particular President Mubarak’s 1989 firing of the popular defense minister, Field Marshal Abu Ghazaleh.

Michael Hanna elaborates his views on the Egyptian military’s role in a presidential transition at Democracy Arsenal. He brings up some of the crucial Mubarak era history (which I didn’t have room for in my NYT piece on the subject), in particular President Mubarak’s 1989 firing of the popular defense minister, Field Marshal Abu Ghazaleh.

Michael writes:

It is hard to pinpoint the parameters of the military’s power within Egyptian society at this juncture. Yes, it is the most respected and coherent organization in the country, but Egypt does not fight wars anymore and the military is not involved in the day-to-day of politics. And, it has not been overtly involved in a presidential succession since 1952. While Anwar al-Sadat and Hosni Mubarak were both military men, they were hand-picked as vice-presidents by the president. There was no real process for the military to be involved beyond the sort of informal vetting that might have taken place internally prior to the their appointments. And it is also worth remembering that both al-Sadat and Mubarak were seen as weak figures with no broad popular legitimacy at the time they assumed the presidency, and, yet, the military regime did not attempt to block the ascension of either man to the post.

From an institutionalist perspective, the central question about Egypt remains what pathways exist beyond the mechanisms of power controlled personally by Hosni Mubarak. In the case of the military, it appears that its power must be substantially weaker than it was in 1970 or 1980, but how much weaker, and what control it has, are open and vital questions.

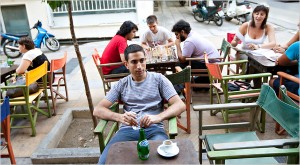

Another Greek Exodus?

While I was traveling I missed this fine story by Niki Kistantonis about the newest generation of Greeks flooding abroad because of the lack of opportunity. For much of its modern history, one of Greece’s most successful exports has been its young. It’s a common story in underdeveloped nations — the initiative-takers, the smart and resourceful self-select for emigration, and take their work ethics and brains abroad. In the early twentieth century and again in the 1950s and 1960s hundreds of thousands of Greeks fled to the diaspora.

While I was traveling I missed this fine story by Niki Kistantonis about the newest generation of Greeks flooding abroad because of the lack of opportunity. For much of its modern history, one of Greece’s most successful exports has been its young. It’s a common story in underdeveloped nations — the initiative-takers, the smart and resourceful self-select for emigration, and take their work ethics and brains abroad. In the early twentieth century and again in the 1950s and 1960s hundreds of thousands of Greeks fled to the diaspora.

Those who remain, especially the ambitious and the well educated, find themselves choked from opportunity. She quotes a recent poll:

According to a survey published last month, seven out of 10 Greek college graduates want to work abroad. Four in 10 are actively seeking jobs abroad or are pursuing further education to gain a foothold in the foreign job market. The survey, conducted by the polling firm Kapa Research for To Vima, a center-left newspaper, questioned 5,442 Greeks ages 22 to 35.

The economic crisis in Greece has taken a huge toll on the country, and heightened generational anxiety. At the same time, economic opportunities are dampened everywhere right now, not just in Greece.

I just spent 10 days in Lebanon, long famed as the most debt-ridden nation in the world. It was striking during this visit to regularly have people ask me whether Greece has surpassed Lebanon in debt. Even one Greek banker I met had to stop and calculate in his head before concluding that Greece was barely ahead of Lebanon in debt-to-GDP ratio.

Greece and Lebanon have painful similarities: impressive human capital, speedy journeys from developing to developed economies, endemic graft, ossified political structures, and diasporas whose economic achievements dwarf those of the metropolis.

Iran on Israel’s border

For as long as I’ve been covering this region, there have been some Israeli officials who describe Hezbollah as a crack division of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and conclude that Iran has literally surrounded Israel.

In the war of rhetoric and symbols, Iran appears only too happy to oblige.

This weekend I visited “Iran Park” in Maroun Al Ras, the Lebanese border village where one of the first and nastiest engagements of the 2006 war was fought. Israeli ground troops got bogged down for days on the ridge at Maroun, and Hezbollah fighters consider it one of their finer engagements of the war.

The Iranian government has funded and designed a lush park near the site of the battle, on the mountainside directly overlooking Israel. In the parking, visitors can stand at an observation point beside an Iranian flag fluttering in the wind, and look directly down at the Israeli hamlets of Avivim and Yir’on.

The Iranian government has funded and designed a lush park near the site of the battle, on the mountainside directly overlooking Israel. In the parking, visitors can stand at an observation point beside an Iranian flag fluttering in the wind, and look directly down at the Israeli hamlets of Avivim and Yir’on.

Through an arcade of ponsiana trees and an arch, past a commemorative plaque crediting President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad with gifting the park to the Lebanese, visitors find terraced playgrounds and picnic spots refreshed with the mountain breeze.

There’s soft-serve ice-cream trucks, grills, and replica of the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem – naturally, topped with an Iranian flag as well. Presumably, Israelis down in the valley can look up and see the Iranian flags and the replica Jerusalem mosque.

Along the path, detailed placards provided educational information about Iran – its population, its provinces, the neighborhoods of Tehran, and so on.

On Sunday mourning the park was already nearly full by 10 a.m. with families that had come to enjoy the cooler temperatures of Jabal Amal.

Three families from the humid coast had assembled under one of the palm-frond roof picnic stations, setting in for a long day grilling and eating.

“Coffee?” said Jihan Muselmani, 35.

“We come here for the clean air,” said Najua Khanafer, 52. “We thank all those who work for our land. Sayed Hassan, Iran, Qatar.”

“This will be the first place the Israelis destroy during the next war,” said Jihan.

“Even if they destroy it, we will build it up again,” said Rabab Haidar, 28.

“If you won’t have coffee, you must at least try these apples,” Jihan insisted, clutching a plastic tub of tiny green fruit. “They come from our own tree.”