Revolutionary Times

Photos: Youmna El-Khattam/Collage: by Nermine El-Sherif

[Published in the Carnegie Reporter. Preview available on Carnegie Corporation website.]

Research on the edge

Even in the early days of Syria’s uprising, it was nearly impossible to do independent research. From early on in the rule of President Bashar al-Assad, which began in 2000, very little leeway was allowed for any work that might challenge the regime. Academics, journalists, political activists, even humanitarian workers were subject to harsh measures of control. The situation worsened after peaceful protests erupted across the country in 2011. Nonviolent activists were imprisoned, exiled, or killed, and armed insurgents took their place. From the start, the conflict restricted movement around the country. Even worse, authorities on the government side and later among rebels wanted to manipulate any research or reporting from their tenuous zones of control. Analysts began to call Syria a “black box,” an unruly place off-limits to credible researchers.

Into this confusion stepped two Syrian-born academics: Omar Dahi, an economist at Hampshire College, and Yasser Munif, a sociologist at Emerson College. They practiced traditional disciplines at reputable research institutions, but they wanted to conduct unconventional research. How were Syrians adapting to the transformation of their society and the disintegration of an old order? Dahi and Munif wanted to bring systematic rigor to studying the experiences of the thousands, eventually millions, of Syrians who were building new modes of self-governance, beyond Assad’s control, or who were adapting to new lives and identities in the maelstrom of exile. They believed they could conduct meaningful social science in the “black box.”

“Most of the research about Syria revolved around geopolitical conflict and strategies, interested in a top-down perspective,” Munif said. “I was interested in the other way around. I wanted to understand participatory democracy, the different ways people were conducting politics after the collapse of the state.”

Like other radical developments that accompanied the Arab uprisings and government backlash, Syria’s crisis demanded sustained scholarly attention. And research in a rapidly evolving war zone, in turn, required support from a flexible and imaginative institution. Dahi and Munif found their backer in the Arab Council for the Social Sciences, a quietly transformative venture that’s been midwifing a network of Arab scholars to more confidently practice a new brand of social science that rises directly from the concerns of a region in turmoil.

Dahi and Munif applied in the fall of 2012 for the first batch of funding offered by the grantmaking organization, known by its acronym, the ACSS. Dahi wanted to study the survival strategies of refugees. By the time his grant had been approved and he began research, the number of refugees had swollen from a few hundred thousand to nearly two million. He partnered with researchers and activists in the region who were devoting much of their time to the urgent needs of resettling refugees and defending their rights. Munif wanted to study the way local people took charge of their own lives and governed themselves. He chose a provincial city called Manbij, in northeastern Syria. By the time he began his field research, government troops had been driven from the city, leaving it in the hands of local civil society groups and rebels.

By 2014, Munif had to interrupt his own work prematurely when Islamic State rebels conquered Manbij. “Without the ACSS, I wouldn’t have been able to do this type of work. They funded the entire project from A to Z,” Munif said. “ACSS is willing to experiment with new types of research, new methodology. With the Arab revolts they are funding some interesting projects that would not get funding from traditional sources.”

Arab social science

It’s worth pausing for a minute to look at the research that came out of Munif and Dahi’s loose collaboration, because it conveys a sense of what a different kind of social science looks like—in the terms of ACSS, a “new paradigm” that addresses questions of concern to people who live in the Middle East and North Africa.

In his work among Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan, Dahi identified ways that humanitarian aid manipulated the politics of the refugees, in some cases fostering deeper sectarian division, and in others strengthening a more inclusive kind of citizenship. At the same time, Dahi helped to build an online portal that will serve as a data resource for other scholars. He found many willing collaborators within the active community of regional researchers, advocates, and activists. Munif has already published extensively on the local governance and decision-making structures he discovered in Manbij, and he’s currently working on a book that counters “the dominant narrative about Syria,” which in his view “reduces the Syrian uprising to violence, chaos, and nihilism.”

This project is but one of dozens supported by the ACSS since it set up shop in 2010 with a tiny staff but grand ambitions to foment change in intellectual life in the Arab world. Formally, the Arab Council incorporated in October 2010 but only hired staff and began operations from its Beirut headquarters in August 2012. The experiment is still young, but after two major conferences to present research, two business meetings of its general assembly, and the third cycle of grants underway, ACSS is moving from its organizational infancy into adolescence.

Still, some might see its mission as exceedingly quixotic: to foster a standing network of engaged activist intellectuals who set a critical agenda and use the best tools of social science to address burning contemporary questions. And all this ambition comes against the backdrop of a region governed by despots for whom academic freedom is in the best cases a low priority, and in the worst, anathema. “We’re enabling conversations that hadn’t taken place,” said Seteney Shami, the founding director of the ACSS. “It’s too soon to say how we’ve affected social science production, but we have created new spaces. I think we have made a difference.”

The method is as straightforward as the idea is bold. Solicit proposals, especially from researchers who aren’t already part of well-funded and established networks, or who are working on different questions than the mainstream Western academy, which still dominates the research landscape. Invite researchers (ACSS-funded or not) from the region to join the ACSS as voting members who ultimately control its policies and agenda. See what happens.

Since doling out its first grants in 2013, the ACSS has awarded $1.162 million to 108 people. Its annual budget has grown from $800,000 in 2012 to close to $3 million in 2015. The first round of research has been completed, and voting members of the Council’s general assembly this year elected a new board of trustees. (There are 58 voting members out of a total of 137 in the general assembly, according to Shami.) It’s been a dizzying journey for a small organization that supports a type of research criminalized throughout much of the region.

The founders and original funders were determined to promote regional scholarship. Carnegie Corporation in particular has aimed much of its funding in the region toward local scholars, with the intention of stimulating and enabling local knowledge production. The Arab Council complements a number of other efforts in the region to strengthen research and social science. New universities, think tanks, and research centers are emerging in the Arabian Peninsula. Arab and Western academics have formed partnerships, sometimes individually and sometimes at the level of academic departments or entire universities. The magnitude of the ACSS’s impact will only become clear in the context of a wide web of related ventures—all of them taking shape at a time of enormous change and pressure.

All across the Middle East and North Africa, academic researchers face daunting obstacles. There are bright spots, like the active intellectual communities in the universities in Morocco and Algeria. But some of the oldest intellectual centers, like Egypt, struggle under aggressive security and police forces as well as university leaders whose top concern is to ferret out political dissent. War has disrupted intellectual life in places like Syria and Iraq. Government money has poured into the education sector in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, but the lack of academic freedom has dulled its luster.

“The Council was conceived at a time when repression was high but the red lines were clear,” Shami said, referring to the years before the uprisings, when the ACSS was in its planning phase. The current logistical challenges underscore the difficulty of the changing conditions for researchers in the Arab region. An organization dedicated to free inquiry, the ACSS chose to incorporate in Lebanon, where it could operate without governmental restrictions and draw on a vibrant local academic community. Even that location is an imperfect choice.

Members from Egypt, for example, now face new restrictions when they want to visit Lebanon. So far it’s not impossible for Arab scholars to travel around the region, but it’s getting harder. Lebanon’s excessive red tape has thrown up numerous hurdles. For example, the ACSS is currently seeking special permission from the government of Lebanon to allow its international members to vote online on internal policy questions. Equally important, according to Shami, is that work permits for non-Lebanese people are becoming more difficult to obtain, which makes it challenging for the ACSS to hire staff from different parts of the region.

Many resources other regions take for granted don’t exist in the Arab region, where governments restrict access to even the most mundane archives. Data about everything from the economy to food production to the population is treated as a state secret. Permits are difficult to secure. Until the ACSS compiled one, there wasn’t even a comprehensive list of the existing universities in the region. It was these challenges that the founders of the ACSS had in mind, but by the time the organization incorporated in borrowed space in Beirut, the ground had begun to shift. Tunisia’s popular uprising in December 2010 began years of political upheaval across the region. The horizons of possibility briefly opened up, until the old repressive regimes returned in full force almost everywhere except Tunisia.

“We started off at a moment of heightened expectations about the role social sciences could play in the public sphere,” Shami said. “Now we’re in a situation that is far worse in every possible way. These are all big shocks for a young institution. But so far, so good. People are saying it’s impossible to work, but the evidence is that they’re still producing.”

Everything all at once

The ACSS put a lot of balls into the air from the start. Its founders wanted to create a standing network for scholars from the region and who work in the region. Their goal was to empower new voices, connect them with established academics, and nurture the relationships over a long term. That way, even scholars at out-of-the-way institutions, or smaller countries traditionally ignored by the global academic elite, might get a hearing. The Council also wanted to integrate Balkanized research communities, bringing together scholars who often published and collaborated exclusively in Arabic, English, or French.

Other long-term goals factor into the project’s design. Some of the grant categories, like the working groups and research grants, explicitly aim to change the discourse in academic social science. Others, like the “new paradigms factory,” intend to bring activists and public intellectuals into conversation with academics. The ACSS is a membership organization; each grantee can choose to become a permanent member with voting privileges—a sort of institutional democracy and accountability in action that the Council hopes will filter into other institutions in the region.

Finally, this summer (2015) the Council will publish its first in-house work, the Arab Social Science Report, a comprehensive survey of the existing institutions teaching and doing research in the social sciences in the region. The ACSS has established theArab Social Science Monitor as a permanent observatory of research and training in the region and hopes to produce a new report on a different theme every two years, in keeping with its role as a custodian as well as mentor of the Arab social science community.

The inaugural survey demanded an unexpected amount of sleuthing, said Mohammed A. Bamyeh, the University of Pittsburgh sociologist who was the lead author on the report and helped oversee the team that produced it. In some cases it was impossible to obtain basic data such as the number of faculty at a university or their salaries. “If you call them, they will never tell you,” Bamyeh said. “For some reason, it’s a secret.”

In the end, however, a year’s worth of legwork produced a surprisingly thorough snapshot of social science in the region. Researchers identified many more academics and other researchers than they expected, and a wider range of periodicals and institutions. Freedom of research turned out to be a better predictor of quality than funding did, Bamyeh said. The quality varied widely, but Bamyeh said social science in the region is “mushrooming.” We may not have appreciated this growth because we don’t have an Arab social science community,” he said. “We have a lot of individuals doing individual research but they are not connected to each other.”

Sari Hanafi, a sociologist at the American University of Beirut, has studied knowledge production in the Arab world and is intimately familiar with the paucity of quality peer-reviewed journals, professional associations, and the unseen scaffolding that supports top-notch research. He was one of the founding members of the ACSS and currently sits on its board, but he is pointed about the bitter challenges impeding research in the region.

“Social science in the Arab world is in crisis,” Hanafi said. “Social sciences are totally delegitimized in the Arab world.” Repressive states wanted only intellectuals they could control, he maintains, so they starved institutions that could produce the large-scale research teams required for any serious, sustained research. The problem has been compounded, Hanafi said, by ideologues and clerics who want to fulfill the role that social science should rightfully play: providing data, assessing policy options, and generating dissent and criticism.

Quality research anywhere in the world depends on money, intellectual resources, and the support of society and the state, according to Hanafi. “In the Arab world, this pact is still very fragile,” he said. “You don’t have a strong trust in the virtue of science.” He hopes that the ACSS can play a part in a wider revival, in which social scientists reclaim their influence and beat back the encroachment from clerics and authoritarian states. “The mission and vocation of social science in this region is to connect itself to society and to decision makers,” Hanafi said. He believes the Arab world needs stronger institutions of its own, including independent universities, governments sincerely committed to funding independent research, and professional associations for researchers. Efforts like the Arab Council can help pave the way.

Participants at the ACSS conferences are encouraged to present and publish in Arabic. The Council also emphasizes the value of its members as a collective network. Pascale Ghazaleh, a historian at the American University of Cairo, said it was “mindblowing” to meet scholars she’d never heard from around the region at the the ACSS annual meeting in Beirut in March 2015. She said she was moved to hear her colleagues discussing their work in their own language. “It was the first time that I’d been surrounded by people who were unselfconsciously using social science terminology in Arabic,” Ghazaleh said. “It’s something to be proud of.”

The language is part of an intentional long-term strategy to anchor the Council and its social science agenda in the region. Although many of its founders have at least one foot in a Western institution, Shami said that “we see ourselves as fully homegrown and firmly based in the region but interacting with the diaspora as well.” The majority of the trustees, for instance, are based in Arab countries.

“It is an ongoing conversation as to who decides the main questions of research for social sciences,” Bamyeh said. “Can there be something like an indigenous social science that has its own methods? It is essential for social sciences in the Arab world to develop a strong sense of their own identity.” As an example he cites an Egyptian sociologist in the 1960s who discovered at the post office a bag of unaddressed letters, most of them containing prayers and pleas for help from the poor written to a popular folk saint. A clerk was about to throw them away. The sociologist took them home and produced a seminal study of Egyptian attitudes and mentality.

That’s the sort of approach that Bamyeh said he hoped to see employed after the Arab revolts. Instead, he was disappointed to find many American sociologists trying to apply existing Western models to the cases of Egypt and Tunisia. “It was an opportunity to acquire new knowledge,” Bamyeh said. “We need an independent Arab social science that feels its own right to ask questions, questions not asked by the European and American academy. It’s not nationalistic, although it might sound that way. It’s really a question of a scientific approach that comes out of a local embeddedness.”

Activist research

The architects of the ACSS have embraced that quest, encouraging research that springs from local problems, and supporting work from outsiders and nonacademics. In Beirut, the ACSS supported an atypical multidisciplinary research team that explored the misuse of public space and the confiscation of people’s homes. As a result of that research project, Abir Saksouk, an architect and urban planner without an institutional home of her own, launched an ongoing public campaign to save the last major tract of undeveloped coastline in Beirut.

Today she is spearheading one of the most dynamic and visible grassroots social initiatives in Lebanon: the Civil Campaign to Protect the Dalieh of Raouche. The Dalieh is the name of the grassy spit of rock that flanks Beirut’s iconic pigeon rocks. Cliff divers used to perform death-defying Acapulco-style style leaps from the Dalieh’s cliffs until last year, when developers suddenly fenced off the last publicly accessible green open space in Beirut. The campaign that Saksouk helped initiate wants to stop the Dalieh from being transformed into a high-end entertainment and residential complex.

“ACSS was a huge push forward,” Saksouk said. It wasn’t the money, she said, so much as the people with whom it connected her. She was mentored by academics, given a platform to publish in Arabic, and introduced to other people thinking about ways to engage with their city. “My activism on the ground informed what I wanted to focus on in my research, and the paper I wrote for the ACSS informed my activism,” Saksouk said.

The Civil Campaign has started a contest, soliciting alternative, public-minded proposals for the Dalieh peninsula. The point, Saksouk said, is to energize a social movement and change the way Beirutis think about their city’s public space. Her research collaborator, Nadine Bekdache, studied the history of evictions, and together the pair explored the concepts of public space and private property. These are theoretical concepts with explosive implications, especially in a place like Beirut where a few powerful families dominate the government as well as the economy.

“A lot of people are sympathetic but don’t think they can change anything,” Saksouk said. “We’re accumulating experiences and knowledge. All this will lead to change.”

Egypt: In the shadows of a police state

In contrast, the clock has turned backward on the prospects for reform and innovation in Egypt, long considered a center of gravity for Arab intellectual life. Egypt has some of the region’s oldest and biggest universities, and historically has generated some of the most important thinking and research in the Arab world. But Egypt’s academy has suffered a long, slow decline as successive dictatorships suppressed academic life, fearing it would breed political dissent.

In the two-year period of openness that began after Hosni Mubarak was toppled in 2011, university faculty members won the right to elect their own deans and expel secret police from their position of dominance inside research institutions. Creative research projects proliferated. The ACSS was just one of many players during what turned out to be a short renaissance. A May 2015 U.S. State Department report on Egypt’s political situation found “a series of executive initiatives, new laws, and judicial actions severely restrict freedom of expression and the press, freedom of association, freedom of peaceful assembly, and due process.”

At least one well-known the ACSS grant winner, the public intellectual and blogging pioneer Alaa Abdel Fattah, languishes in jail; he was detained before he could complete the paperwork to start his research. Officials even took away his access to pen, paper, and books after his prison letters won a wide following.

Universities have seen a severe decline in academic freedom and some researchers have stopped working or have fled. Outspoken academics like Khaled Fahmy, a historian who has been a critic of military rule and also a spokesman for freer archival access, are waiting out the current turmoil abroad. Political scientist Emad Shahin (who left Egypt and now teaches at Georgetown University) was sentenced to death along with more than a hundred others in May 2015 in a show trial. Some Egypt-based researchers have left since 2013, many grantees remain. The ACSS continues to receive applications from Egypt, and has become all the more vital to that country’s scholars.

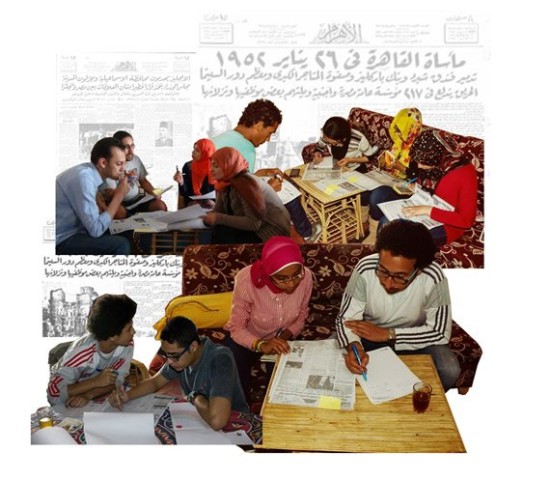

Cairo native and historian Alia Mossallam used her research grant to hold an open workshop about writing revolutionary history. As protests roiled the capital, Mossallam quietly organized a workshop that drew 20 people, some from the academic world, some activists, and some professionals and workers who were intrigued by her proposal to study the historiography of “people who are written out of histories of social movements and revolutions.”

Tucked away on an island in the Nile in Upper Egypt, Mossallam’s workshop brought professional historians together with amateur participants. They studied the history of Egyptian folk music and architecture, they looked at archives and newspaper clippings, and then the students used their new skills to produce historical research of their own. Mossallam carefully avoided politics in her open call for workshop participants, but any inquiry into the history of revolution and social movements at Egypt’s present juncture is by nature risky.

Contemporary politics might be a third rail, but in her workshop the Egyptian participants could talk openly about past events like the uprising and burning of Cairo in 1952, or the displacement of Nubians to build the Aswan High Dam. At a time when political speech has been banned, history offers a safer way to talk about revolution. “These workshops are a search for a new language to describe the past as well as the present,” Mossallam said. “Watch out for how you’re being narrated. A lot of the things the participants wrote engaged with that fear, the struggle to maintain a critical consciousness of a revolution while it’s happening.”

Her project wouldn’t have been possible without the Arab Council’s forbearance. The Council encouraged her to find creative ways to engage as wide an audience as possible and gave her extra time to recalibrate her project as conditions in Egypt changed. No other Arab body gives comparable support to Arab scholars, Mossallam said. “They ask, are we asking questions that really matter?” she said. “Are we trying to reach a wider public?”

Can it last?

Sustainability remains an open question. Although the ACSS is registered as a foreign, regional association under Lebanese law and considers itself a regional entity, the organization currently depends on four funders from outside the Arab world for its budget: Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Ford Foundation, the International Development Research Centre of Canada, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. If at some point in the future those funders turn their attention elsewhere, the ACSS, for all its promise, could quickly reach a dead end. According to Shami, “It’s as sustainable as any other NGO that depends on grants.”

While it’s politically tricky for an Arab institution to take Western money, funds from various regional sources can come with strings attached. Ideally, Shami said, the ACSS would like to find acceptable funding sources from within the region.

The Arab Council’s accelerated launch has attracted wide interest, creating new challenges as the organization matures. “We’ve built up a lot of expectations. People think we have unlimited resources,” Shami said. “We might be coming up against hard times. We might be starting to disappoint people.” Just as important as money is the political structure of the region. Lebanon, Tunisia, and Morocco remain the only relatively free operating environments for intellectual work in the region, and that freedom is always under threat from militant movements, authoritarian parties, and regional wars.

Deana Arsenian, Carnegie’s vice president for international programs, attended the March 2015 meeting and was impressed by the enthusiasm of the several hundred participants, whose optimism for research far exceeded their expectations for their region’s political future. “The act of creating a network across multiple countries is in and of itself a major feat, given the realities of the region,” Arsenian said. “While it’s a work in progress and many aspects of the association have to be worked out, the interest among the members in making it succeed seems very strong.”

ACSS came at a moment of great change and opening in the Middle East, and was rooted in a region that needs to be heard from. From the beginning the ACSS has intentionally included all those who reside in the Arab region regardless of ethnic or linguistic origins, as well as those in the diaspora. As it moves past the startup phase, the Arab Council’s scholars will have to decide whether their aim is to increase the visibility in the wider world of scholars of the region, or whether it’s to create a parallel universe. It will also have to grapple with its definition: what is an “Arab” council? Shami herself is of Circassian origin, and there are plenty of other non-Arab ethnicities and language groups in the region: Kurds, Berbers, and so on. Many of the early success stories in the ACSS are geographical hybrids, trained by or based at Western institutions, which she points out reflects the global hierarchies of knowledge production.

The Council might also have to refine the scope of work it supports. So far, in the interest of transparency and interdisciplinary research, the ACSS has been very flexible and open to all communities of scholars, knowing that as a result the work of its grantees will be uneven. Another question is whether, once the novelty wears off, the ACSS conference will become a genuine source of scholarly prestige for social scientists. Its second annual conference, in March of this year, attracted four applicants for every presentation slot. Almost nobody who was invited to present dropped out.

Arab Council has already identified a greater breadth of existing scholarship in the region than its founders expected. Over time, it will gauge the quality and rigor of that work. “It’s too early to see the dividends or the fruits, because these fruits depend on how social science is professionalized or institutionalized,” Hanafi said.

Dahi, the economist from Hampshire College who researched Syrian refugees, has stayed involved with the ACSS, helping to organize its second conference this year. Regional research has grown harder, he said, because of the “climate of fear” in places like Egypt and the impossibility of doing any research at all today in most of Syria, Iraq, and Libya. “The carpet is shifting under our feet in ways that academics don’t like,” Dahi said. “Academics like a stable subject to study.”

He believes the Council will face a major test over the next years as it shifts from dispersing grants to pursuing its own research agenda, like other research councils around the world. “The key challenge will be this next step, because you need to create this tradition of quality production of knowledge,” Dahi said. “I’m optimistic. Supply creates its own demand. I don’t believe that in economics, but I do believe it in knowledge production.”

A new brain trust for the Middle East

PABLO AMARGO FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT—In any American university, what the six researchers in this room are doing would be totally unremarkable: launching a new project to use the tools of social science to solve urgent problems in their home countries.

But for the young Arab Council for the Social Sciences, this work is anything but routine. The group’s fall meeting, initially planned for Cairo, was canceled at the last minute when Egyptian state security agents demanded a list of participants and research questions. The group relocated its meeting to Beirut, meaning some researchers couldn’t come because of visa problems. Still others feared traveling to Lebanon during a week when the United States was considering air strikes against neighboring Syria. Ultimately, the team met in an out-of-the-way hotel, with one participant joining via Skype.

Their first, impromptu agenda item: whether any Arab country could host their future meetings without any political or security risk.

The council’s struggle reflects, in microcosm, a much bigger problem facing the Middle East. With old regimes overthrown or tottering, for the first time in generations a spirit of optimism about change has swept through the region. The Arab uprisings cracked open the door to new ideas for how a modern Arab nation should govern itself—how it could rebalance authority and freedom, religious tradition and civil rights. But a key source of those new ideas is almost completely shut off. With few exceptions, universities and think tanks have been yoked under tight state control for decades. Military and intelligence officials closely monitor research, fearing subversion from political scientists, historians, anthropologists, and other scholars whose work might challenge official narratives and government power.

Just one year after its launch, the ACSS is hoping to fill that vacuum, giving backing and support to scholars who want to do independent, even critical thinking on the problems their societies face. It’s a daunting order in a region where for generations talented scholars have routinely fled abroad, mostly to Europe and North America.

“There’s been almost a criminalization of research here,” says Seteney Shami, the Jordanian-born, American-trained anthropologist tapped to get the new council running. “We want to change the way people think about the region.”

It took nearly five years of planning, but the new council is now finishing its first year of operation. It has awarded roughly $500,000 to 50 researchers. Its goal is ambitious: to build an enduring network that will connect individual researchers who until now have mostly labored alone, under censorship, or overseas. The council aims to give those thinkers institutional punch—not just funding for projects that aren’t popular with local regimes or Western universities, but muscle to fight authorities who still maneuver to block even the most innocuous-sounding research missions. Today issues of ethnic, sectarian, and sexual identity are still taboo for governments—and they’re precisely the focus for most of the researchers who met in Beirut.

Shami and the other founders envision the council as only a first step, helping push for new openness in universities and in publishing. Ultimately, they believe, it stands to change not only how Arab countries are perceived abroad, but the way those countries are governed. Given the incredible turbulence in the Arab world today, it’s easy to see why a new flowering of social science is needed—and also why it’s a risky proposition for whoever hopes to set it in motion.

***

WHEN WE THINK about where ideas come from, we often picture lone thinkers toiling indefatigably until they achieve their “eureka” moments. But in fact, the ideas that change the way we organize or understand our daily world grow most readily from ecosystems that can train such scholars, test their claims, and ultimately spread and promote their new thinking. The modern West takes this system for granted; universities are perhaps the most important nodes in a network that also includes foundations, think tanks, and relatively hands-off government funding agencies.

Even societies like China, with its tradition of centralized state control, support a vigorous web of universities and institutes that produce and test ideas. In China, the government might drive the research agenda—rural educational outcomes, say, or international trade negotiations—but researchers are expected to produce rigorous results that stand up to outside scrutiny.

Not so in the Arab world. Despite a historic scholarly tradition, and a vigorous cohort of contemporary thinkers, the intellectual institutions in Arab countries are today almost universally subordinated to state control. As the dictators of the 1950s matured and grew stronger, they feared—correctly—that universities would nurture political dissent and that students were susceptible to free-thinking. (Even today, groups like the Muslim Brotherhood induct most of their leaders into politics through university student unions.) So they dispatched intelligence officers to control what professors taught, researched, and published, and to curtail student activism of a political flavor.

To the extent that think tanks, institutes, and journals were allowed to exist at all, they became either government mouthpieces or patronage sinecures. Plenty of individual scholars have continued to work in an independent vein, and many do research or publish work outside the influence of the ruling regime. For the most part, though, they do so abroad; those who speak openly in their home countries have often encountered gross repression, like the Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim, an establishment thinker who was imprisoned in 2000 for taking foreign grant money. His prosecution—despite his close ties to the ruling dictator’s family— served as a reminder to other scholars not to stray too far from the state’s goals.

The obstacles to researchers who hope to confront the region’s problems run even deeper than that: in most Arab nations, even basic data on public issues like water consumption, childhood education, and women’s health are treated as state secrets. So are government budgets, and anything to do with the military, the police, and industry. Egypt still tightly guards access to land registries running as far back as the Ottoman Era; Lebanon famously hasn’t conducted a census since 1932, and refuses to release any government data about the population size or its religious composition. International agencies like the World Bank are allowed to conduct surveys and research as part of development aid projects, but only on the condition that they keep the data confidential.

As a result, great Arab capitals like Damascus, Beirut, Baghdad, and Cairo, once among the world’s great centers of learning, have suffered a systematic impoverishment of intellectual life, especially in the realms in which it is now most needed.

***

IN MANY WAYS Seteney Shami’s career illuminates those challenges precisely. She left her native Jordan first for the American University of Beirut and then to earn an anthropology PhD from the University of California at Berkeley. Even as a young scholar, she knew she might face problems at home simply for writing about matters of identity among her own ethnic group, the minority Circassians, so she had her dissertation removed from public circulation. In the 1990s, she returned to the Middle East and built a well-regarded graduate program in anthropology at Jordan’s Yarmouk University—one of few rigorous graduate-level social sciences departments in the region. The experiment was short-lived, collapsing after only a few years when government patronage hires swamped the university faculty. Several scholars, including Shami, left.

She spent the next decade at US-funded foundations, working in Cairo for the Population Council and later in New York for the Social Science Research Council. She found that the scholars with whom she collaborated—and to whom she sometimes gave grants—relished the networks they built and the ideas that flowed when they had a chance to work with colleagues from different Arab countries, as well as in Europe and the United States. But there was a hitch: When the grant money ended, so did the network. In the West, such a change wouldn’t matter so much; the scholars would always have their home institutions to fall back on. Not so for a scholar in Jordan or Egypt, whose home institution might be far from supportive of his or her work.

“There is no institutional incentive to produce research in most Arab universities,” says Sari Hanafi, a sociologist at the American University of Beirut who is on the board of the new council. Hanafi conducted his own study of academic elites in the region, and discovered that most regional research was confined to safe descriptive projects—“production that will not question religious authority or the political system.” Essentially, it’s scholarship that doesn’t produce any new knowledge, or offer the possibility of change.

So a group of scholars including Shami and Hanafi began to conceive of something that would rectify the problem. Their vision isn’t a “think tank” in the Washington sense, but really almost a substitute for what universities do, creating a new and permanent forum to research, talk about, and solve serious social problems, outside government influence.

They secured funding from the Swedish government and later from Canada, the Carnegie Corporation, and the Ford Foundation. Among Arab countries, only Lebanon had laws that allowed a foreign international organization to operate free from government interference; even here, it took two full years for ACSS to clear all the red tape. In a way, the group’s timing was fortuitous: By the time the organization came online in 2011, with a few dozen scholars participating, the Arab uprisings were in full swing.

The first projects illustrate the flair ACSS is bringing to the sometimes stuffy world of social science. One study focuses on inequality, mobility, and development, and has brought together economists and other “hard” social scientists to explore issues like the impact of refugees from Syria’s civil war. A second, called “New Paradigms Factory,” unabashedly seeks to midwife the region’s next big ideas, asking scholars to challenge its dominant notions of sovereignty, national identity, and government power. The third major project, “Producing the Public in Arab Societies,” probes minority identity, community organizing, and alternative media sources—sensitive issues that governments steer away from, but that will be key to any new ordering of Arab civic life.

***

SOME AMONG the inaugural crop of researchers worry that despite its forward-looking visions, the window for an experiment like the Arab Council for the Social Sciences might already be closing. Two years ago, when Shami recruited her first team of scholars and grant recipients, a wave of optimism was washing over the Arab world. “It was a time to be brave, to test the boundaries of free expression,” she said.

Now, many of the same old restrictions have returned: Egyptian secret police, who had backed off after dictator Hosni Mubarak’s fall, resumed their open scrutiny of intellectuals after the military coup in July. Qatar, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates, fearing revolts from their own citizens, have also tightened their approach to academic inquiry, shutting down local research institutes and banning critical academics from attending conferences and teaching at international universities. Several of the scholars who met in Beirut as part of the “Producing the Public” working group declined to speak on the record even in general terms about the ACSS, fearing that any publicity at all might interfere with their work.

The first ACSS projects will take several years to yield results, and Shami says the long-term impact will depend, in part, on whether Arab governments continue to actively persecute intellectuals they perceive as critics. Meanwhile, Shami says, the group intends to go where it is most acutely needed—funding the edgiest and most relevant scholarship, and pushing for more open access to archives and data. To make up for the lack of regional peer-reviewed journals, it might begin publishing research itself. With the grandiose-sounding goal of transforming the entire discourse about the Arab world, Shami is aware that ACSS might fail; but she’s not interested, she said, “in biding our time and holding annual conferences.” If it proves necessary, she said, ACSS might create its own university.

Already, though, ACSS has had some visible impact. Omar Dahi, an economist at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, won a grant from the new council to study the way Syrian refugees are supporting themselves and how they are transforming the nations to which they’ve fled. He’s spending the semester in Beirut, and he expects to produce a series of articles that will bring rigor to a heated and topical policy debate. The council, he says, allows Arab scholars “to answer their own questions, and not only the questions being asked in North American and Western European academia.”

“It’s not easy, and ACSS alone is not going to be able to do it,” Dahi said. “But you have to start somewhere.”