Trying to make a renaissance at AUB

[Published in The Boston Globe Ideas.]

BEIRUT

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY of Beirut used to tally its influence by the number of its alumni among the region’s monarchs, presidents, and prime ministers. Today, AUB’s boosters have stopped counting heads of state but remain as obsessed as ever with reclaiming the luster of an institution that remains the best-reputed and most independent university in the Arab world.

That’s no mean feat in an era when authoritarian rulers in most Arab states are using the tools of surveillance, torture, and state harassment to curtail freedom of inquiry.

Yet today, in the heart of this region’s historical turbulence, AUB has begun an ambitious effort to make — or remake — itself as a great Arab university. For the first time in its 150-year history, AUB inaugurated a Lebanese president this January, a biologist and medical doctor named Fadlo R. Khuri. He has begun quietly but steadily breaking taboos in a systematic effort to emerge from four decades of hibernation and reconstruction, hoping to restore AUB’s ambitions and connect unapologetically to Lebanon and the Arab world.

“We can’t sit there and say we’re going to wait for the country and the Arab world to get its act together,” Khuri said in an interview in his corner office at College Hall, a stone building with a New England clock tower built in 1871. “We are committed to being excellent without the asterisk — not excellent ‘for Lebanon’ or excellent ‘for the Arab world.’ ”

Khuri’s bold talk about shedding mediocrity, fighting corruption, and competing directly with top universities around the world marks a vivid departure for AUB, which until recently was still a deeply scarred institution. In 1984, gunmen murdered AUB president Malcom Kerr — an American famous for his magisterial study of Arab politics — inside College Hall as he was entering his office. In 1991, the last year of the civil war, a bomb blew the building and iconic clock tower to smithereens. Reconstruction began immediately, and College Hall reopened in 1999.

It took 14 years from Kerr’s assassination for AUB’s president to risk living in Beirut at all — during the interim, the university was run remotely from an office in New York. Today, the campus gleams like any well-funded small liberal arts college with a gifted landscaper.

But in many important ways, AUB has not yet begun to recover from the hiatus violently imposed by the civil war. Tenure was scrapped during the war years and only now, in Khuri’s first year, has AUB decided to reinstate it — a necessary precursor for the university to compete with top-tier research institutions. AUB’s leadership is so afraid of sectarian politics and student activism that it bans the mention of political party names on campus and so heavily regulates debate at a Hyde Park-style speaker’s corner that students stopped showing up even at the peak of the Arab uprisings.

And in a country beset with multiple crises and a crippling political divide, its preeminent university seems often strangely genteel and detached, with only glancing mention at public events of pressing realities like the next-door war in Syria, the 1.5 million refugees in Lebanon, and the often violent struggle between Lebanese sectarian warlords underwritten by expansionist regional powers.

The stakes are high in a region where scholarship is severely restricted; for example, researchers are almost entirely unable to work in Egypt today because of restrictions on academics and the routine detention of scholars. Last month, an Italian graduate student was allegedly murdered by Egyptian security officials. The greater the limits, the more independent scholarship is sorely needed. Institutions of state are in shambles, and political discourse, even five years after a wave of mostly failed popular uprisings, remains in a state of suspended animation.

Lebanon is better off than many of its neighbors in the Arab world, and that’s saying something when the most basic essentials of life and government barely function: For nearly two years, Lebanon has been unable to elect a president, and for nearly one, it hasn’t been able to dispose of the nation’s garbage.

Khuri’s predecessor was more likely to chide faculty members for failing to go through proper channels when reporting litter on campus than for failing to take a public stand on the issues of the day. Reams of leaked documents published in the Lebanese press detail allegations of kickbacks, nepotism, and corruption in the university’s procurement and finances — especially significant considering that AUB is the largest employer in the entire country of Lebanon after the government.

In a refreshing change of tone, Khuri has dispensed with the notion that civility, or even pure scholarship, is more important than relevance. He wants his deans to define the criteria for tenure and promotion to value service to Lebanon.

“Yes, we want to have international impact. But we were put here to have an impact locally and regionally,” Khuri said. “I would rather have my engineer who designs a retractable school for Syrian refugee kids spend a lot of time and get that right than necessarily publish 20 articles and get cited.”

AMHERST COLLEGE GRADUATE Daniel Bliss founded the Syrian Protestant College in 1866, with high hopes to spread Christianity in the Levant. Instruction was in Arabic, and Bliss planned to quickly turn it over to local leadership. Within decades, however, Bliss had clashed with a faculty member who wanted to teach Darwin’s theory of evolution and shut down a student protest movement. English replaced Arabic, and “native instructors” were relegated to secondary status. Eventually, the institution gave up on its failed missionary aims and in 1920 adopted it modern name, the American University of Beirut.

It became a cornerstone of an era of ferment in Arab political life. Liberals, nationalists, revolutionaries, communists, and others were agitating throughout the Levant and the Arab region. In the half century that followed — through World War II and decolonization, the establishment of Israel and the displacement of Palestinians, and a long cycle of regional wars — it was an epicenter of political activism and research in and about the Arab world.

Until the Lebanese civil war broke out in 1975, AUB hosted some of the most influential and prolific figures of Arab political and intellectual life. Arab nationalists, Lebanese chauvinists, leftists, Palestinian revolutionaries, and countless others sharpened their arguments in AUB’s lecture halls and the nearby cafés on Bliss Street.

But the civil war undid the university. After Kerr’s murder, the university hunkered down, improvising in order to continue teaching students throughout the ebbs and flows of violence. AUB survived by insulating itself from its surroundings. Once a petri dish of politics, AUB tried to transform into a sterile politics-free zone. When Lebanon’s fratricidal war ended in 1991, AUB rebuilt a gleaming campus that now enrolls 9,000 students and employs 800 full-time faculty members. But the university never fully recovered its luster or reputation. Top scholars were deterred by the absence of tenure, and many would-be faculty avoid Lebanon, considering it unstable or dangerous.

“It’s always been a real crossroads,” said Betty S. Anderson, a historian at Boston University whose 2011 history of AUB remains the definitive study of the school.

But it is still a draw because none of its new competitor universities can match Beirut’s intellectual climate. “You still have academic freedom at AUB,” Anderson said. “There are red lines you can’t cross, but there is still an openness and freedom to maneuver here.”

The failure of lavishly state-funded universities in the Gulf suggests that money can’t buy excellence in research or education, and AUB, diminished as it is, remains the Arab world’s top university.

AUB is making an effort now to reverse decades of decline and reestablish a distinctly, and distinctly Arab, renaissance. Its challenges mirror those that face researchers across the Arab world: political pressure to avoid sensitive topics, corruption, and instability.

Research is dramatically underfunded in the Arab world ($10 per capita is expended for scientific research in the Arab world compared to $33 in Malaysia and $575 in Ireland) and subject to extreme political pressure, according to an ongoing multiyear study of research in the region by an AUB sociologist, Sari Hanafi, and Rigas Arvanitis, a sociologist at the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement in France.

This spring at an AUB symposium, they released their new book, “Knowledge Production in the Arab World: The Impossible Promise,” about the dismal state of Arab research. Across the region, the sociologists found, Arab researchers suffer a double bind, discredited by religious authorities as well as by authoritarian states.

Lebanon had fared slightly better, Hanafi said, but only because of international funding. “When we talk about producing knowledge, we always should ask what is its purpose,” Hanafi said in an interview. “AUB’s international success comes at the expense of local relevance.”

Much of the research done in the Arab world is set by the agenda of foreign donors, Hanafi said, or is locally driven but of poor quality or published on platforms only read in one country.

“There will be no important research in the Arab countries without freedom to think, speak, and write,” Hanafi and Rigas wrote in their book. “Important research will be done elsewhere, and far from the actual needs and desires of the Arab population.”

KHURI IS CANDID about AUB’s fallen stature, and about the need to think beyond the university’s American identity to its Arab and Lebanese role and responsibilities. But striking a balance will be tricky. Until the civil war era, the US State Department was a major funder and considered AUB an arm of Cold War foreign policy. AUB steadfastly refused to cast itself as a Lebanese institution in part as a hangover from its imperial roots but also out of a desire to protect itself from the sectarianism, political violence, and graft that pervade Lebanon.

Born in Boston, Khuri finished high school in Beirut and then returned to the United States, where he studied at Yale and Columbia universities and finished his medical training at Boston City Hospital and Tufts. Khuri salts his conversation with references to the Red Sox and Celtics; as a teenager in Lebanon he listened to Sox games on Armed Forces radio. He carefully describes himself as card-carrying member of the ACLU with family roots in Beirut and AUB — someone who can navigate Lebanon’s local political culture without getting sucked into sectarian politics.

“I think it’s high time after 150 years that one of us was qualified enough to lead this institution,” Khuri said. “I get AUB, and I get Lebanon, and I get the US.”

Some of AUB’s problems are familiar: Students complain about unsustainably high tuition and the difficulty finding jobs. Faculty complain of low pay and tone-deaf administrators.

Others are of an entirely different nature. Faculty search committees lose compelling applicants who drop out when a bomb goes off in Beirut. Lebanese government officials approve work permits for some of the foreign faculty but illegally delay or withhold permission for faculty from Syria, the Palestinian territory, and some African countries. AUB developed its own electricity and water infrastructure during the war, but, like the rest of Lebanon, it struggles from chronic shortages and resource mismanagement.

Despite the official ban on politics, student clubs with tame names run for council elections as Trojan horses for Lebanon’s sectarian factions. The student newspaper publishes a handy guide explaining that the Cultural Club for the South fronts for the Shia organization Hezbollah, the Youth Club for the Sunni Future Movement, and so on.

Speaker’s Corner, a prominent feature of campus life until 1974, was brought back in 2010 but quickly faded away. Administrators, terrified that open debate about politics could quickly escalate into sectarian strife, carefully vetted topics and heavily coached student speakers. Like many public events on campus about polarizing contemporary topics, the result was so anodyne that students lost interest even at the peak of the Arab revolts that swept the region in 2011. Speaker’s Corner is once again on hiatus, and students said that faculty members tell them it’s better this way, since the young don’t yet have the “maturity” to discuss sensitive political matters.

Suspicion borders on paranoia as members of the AUB community track the relative number of supporters of each of Lebanon’s main political factions. Some whisper darkly that Hezbollah has taken over the faculty; others point to recent hires to argue that the rival Future movement now dominates AUB. Any perception that the university has sunk into the clutches of one faction or another could hurt the institution’s standing and expose it to pressure, threats, or even violence.

In order to eliminate the perception of sectarian bias, university admissions stripped out personal artifacts like essays or portfolios; Khuri wants to reverse that.

As Lebanon’s national crisis has reached a breaking point over the failure to dispose of garbage since July 2015, political activism among AUB faculty has quickened. So far, perhaps as part of his commitment to the Arab nahda, or renaissance, Khuri has let it flourish.

Dozens of enraged professors banded together in the fall to propose technocratic fixes to the Lebanese garbage crisis and have become a major force in an accountability movement that paints all Lebanon’s politicians as party to a colossal failure. The faculty proposals have emerged as the main alternatives to government policy.

An AUB economist named Jad Chaaban has spearheaded a group that’s running a slate of candidates for the Beirut city council elections this spring. If it does well, the group could emerge as a new, antisectarian political party in the next national parliamentary elections — a return with a bang of AUB’s legacy as a political player in its own right.

With several of Lebanon’s entrenched politicians on AUB’s board, Chaaban said that Khuri will need thick skin to resist encroachment on faculty autonomy. “They say they welcome dissenting voices,” Chaaban said. “So far they have left us alone.”

It’s not nostalgia, it’s common sense

[Published in Medium.]

The first time I told a group of graduate students that laptops and cell phones were forbidden in my classroom, the outcry was instantaneous. Why was I acting like such an old fogey? It was a seminar about war writing, in a wired classroom in the Internet age. To further confuse things, I am a technophile and was not that much older than my students at the time. I didn’t look like an enemy from the other side of the digital divide — so why the cruelty and ignorance?

By the end of the war-writing course, no one was complaining about the phone and laptop ban. Technology, like everything, has its place, and a good educator (or a good anything) is always open to the right tools at the right time. When we conducted Skype interviews with faraway subjects in Gaza or Iraq, we used a laptop and projector. Out of the classroom, much of the research and collaborative work occurred online, and when needed, students were welcome in the classroom to use their devices for presentations or to look up something relevant.

In this particular classroom, I was trying to teach a specific kind of thinking and writing, which benefitted from a technology-sterile environment. We were collaborating to understand the architecture of powerful stories, the process of gathering narrative strands and information in the fog of war, and what each individual needs to do to transcend assumptions and approach their own voice as a writer. These were intellectually intense and intimate group discussions. The learning that took place required trust and a sense of community that in this case was in part abetted by the act of putting aside our devices for the duration of our meetings.

I’m open to the possibility that in some classroom environments, screens might add something. In a large lecture class with hundreds of students, a shared Twitter handle might foster participation and connection. I’m not sure. But I figure my challenge as a teacher (or a conversationalist for that matter) is to be interesting. If I fail, if I am boring, nothing will change that: not a common hashtag, not PowerPoint slides crisscrossed by an animated Tintin, not a simultaneous online dialogue.

Fans of technology in the classroom, like Michael Oman-Reagan, often cite efficiency; note-taking is quicker, and so is access to online databases and other enriching resources. That’s true, but it’s not always an advantage to be able to jump down a rabbit hole, even a fascinating one; back in the “old” days classes didn’t instantly consult the encyclopedia sitting on a shelf in the back of the room.

Saving time doesn’t necessarily mean better learning or information processing. Many of us long knew anecdotally what science has increasingly made clear: humans aren’t capable of multi-tasking — instead, they just shift rapidly and sequentially between different tasks, degrading their focus on all of them. Even when I’m teaching, I momentarily lose focus if I see an alert for an important new email or a particularly juicy news item.

When I’m teaching, the goal is to communicate. I need the attention of my students with as few distractions as possible. Once I have their attention, it’s up to me to hold and engage it.

In small seminar courses, I found the quality of interaction increased consistently the less screen time we had. It’s not that different from the rest of my life. When I’m writing or researching on my computer, I hate to be interrupted. And conversely, while I love staying in touch with friends and sources around the world through instant messaging platforms, when they ping me while I’m walking somewhere I find myself either bumping into things or missing key parts of the exchange. Satisfaction in my marriage grows when my spouse and I maintain a border between our digital and flesh-and-blood “communications platforms.” When I’m forced to use my laptop during an interview, I find the quality of the conversation always suffers, because of the lost eye contact and imperceptible shift of the center of gravity to the glowing screen.

There are some decent arguments to be made for technology, and some of them point to rare occasions or exceptions when the classroom door ought to be opened to technology. But all too often one encounters fatuous whining. You need Evernote to write your thesis? That’s great, you’re welcome to it. But you don’t need to input our in-class conversation directly onto your laptop. Similarly, it’s hard to take seriously someone who compares the need for laptops in a lecture class to eyeglasses, or banning laptops to the medieval practice of tying up left-handed people because they carry the mark of the devil.

At Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, I spent three hours a week with my seminar students. They had plenty of time outside of class to create stickies to remember tasks, organize book-length projects on Scrivener, or to partake in any of the plethora of everyday technological wonders on which all of us rely. No one says don’t use these things. But why the drama when someone requires you to wait an hour before you do?

A smart, adaptable and resourceful person in today’s world ought to know how to draw on the vast resources of the wired world, amplifying their intellectual power through digital tools and online resources. She also ought to know how to thrive when those tools are out of reach. Anyone who argues that it’s always better to incorporate digital tools into a classroom setting (or any other human interaction, for that matter), is as much a fool and absolutist as the technophobe fogey who never wants to see a laptop or phone.

Technology fetishists sometimes get confused when someone asks them to put away their phone or shut their laptop. They mistake their comfort with technology with a right — specifically, a misguided, nonexistent right to use their technology whenever they want and however they want.

Here’s where the techno-evangelists really lose perspective. They seem to think that their online access, and their gadget comfort zone, is a God-given entitlement of which they must not be deprived for an instant. And while it’s not so with every teacher or in every classroom, that’s another learning experience that I was delighted to give my students: the opportunity to be bored without recourse to the dopamine-squirt of seven-second feeds.

There’s a whole world of ways to tune out, and while I’m glad today that some of them involve the information and interactions on my phone screen, I’m glad that just as many involve staring out a window, or at a point just beside a speaker’s head, or simply and honestly falling asleep. I don’t begrudge students who pass out or let their minds drift, although their class participation grade would suffer; and I certainly didn’t mind if my students, who were after all adults, popped out of the classroom to take a phone call or deal with an important email.

My responsibility as a teacher was to stimulate and engage my students. If I failed to do that, they were welcome not to take my class, or to turn their thoughts elsewhere. Nothing about the digital age, however, says I have compete hand-to-hand with a screen connected to the Internet. There are plenty of things I can do on my computer or phone that, in the moment, would beat out the real world. My screen life might even be more engaging than a class full of students I’m supposed to be teaching, or a lout I’m interviewing, or a street riot I’m trying to navigate. Time and again, though, I make the choice to disconnect from my devices for a spell and engage with something else — even when that something disappoints, tires, or simply makes demands of my mind.

Any teacher who asks their students to do the same thing for an hour or a school day isn’t a luddite shunning the marvels of a technologically-enabled classroom. They’re a human being, and they’re doing those students a favor.Those who panic shrilly at the prospect of an entire class period without their devices might find that learning and living without a computer for an hour or two at a time can be quite a thrill. And when it’s not, being bored without a screen has its benefits too.

A new brain trust for the Middle East

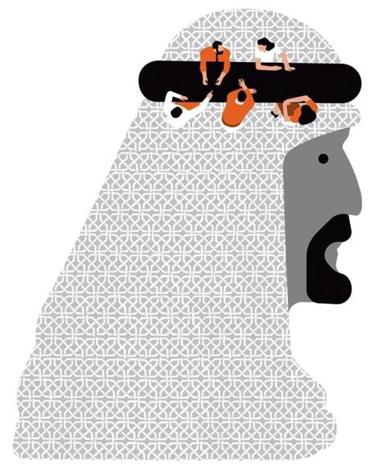

PABLO AMARGO FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE

[Originally published in The Boston Globe Ideas section.]

BEIRUT—In any American university, what the six researchers in this room are doing would be totally unremarkable: launching a new project to use the tools of social science to solve urgent problems in their home countries.

But for the young Arab Council for the Social Sciences, this work is anything but routine. The group’s fall meeting, initially planned for Cairo, was canceled at the last minute when Egyptian state security agents demanded a list of participants and research questions. The group relocated its meeting to Beirut, meaning some researchers couldn’t come because of visa problems. Still others feared traveling to Lebanon during a week when the United States was considering air strikes against neighboring Syria. Ultimately, the team met in an out-of-the-way hotel, with one participant joining via Skype.

Their first, impromptu agenda item: whether any Arab country could host their future meetings without any political or security risk.

The council’s struggle reflects, in microcosm, a much bigger problem facing the Middle East. With old regimes overthrown or tottering, for the first time in generations a spirit of optimism about change has swept through the region. The Arab uprisings cracked open the door to new ideas for how a modern Arab nation should govern itself—how it could rebalance authority and freedom, religious tradition and civil rights. But a key source of those new ideas is almost completely shut off. With few exceptions, universities and think tanks have been yoked under tight state control for decades. Military and intelligence officials closely monitor research, fearing subversion from political scientists, historians, anthropologists, and other scholars whose work might challenge official narratives and government power.

Just one year after its launch, the ACSS is hoping to fill that vacuum, giving backing and support to scholars who want to do independent, even critical thinking on the problems their societies face. It’s a daunting order in a region where for generations talented scholars have routinely fled abroad, mostly to Europe and North America.

“There’s been almost a criminalization of research here,” says Seteney Shami, the Jordanian-born, American-trained anthropologist tapped to get the new council running. “We want to change the way people think about the region.”

It took nearly five years of planning, but the new council is now finishing its first year of operation. It has awarded roughly $500,000 to 50 researchers. Its goal is ambitious: to build an enduring network that will connect individual researchers who until now have mostly labored alone, under censorship, or overseas. The council aims to give those thinkers institutional punch—not just funding for projects that aren’t popular with local regimes or Western universities, but muscle to fight authorities who still maneuver to block even the most innocuous-sounding research missions. Today issues of ethnic, sectarian, and sexual identity are still taboo for governments—and they’re precisely the focus for most of the researchers who met in Beirut.

Shami and the other founders envision the council as only a first step, helping push for new openness in universities and in publishing. Ultimately, they believe, it stands to change not only how Arab countries are perceived abroad, but the way those countries are governed. Given the incredible turbulence in the Arab world today, it’s easy to see why a new flowering of social science is needed—and also why it’s a risky proposition for whoever hopes to set it in motion.

***

WHEN WE THINK about where ideas come from, we often picture lone thinkers toiling indefatigably until they achieve their “eureka” moments. But in fact, the ideas that change the way we organize or understand our daily world grow most readily from ecosystems that can train such scholars, test their claims, and ultimately spread and promote their new thinking. The modern West takes this system for granted; universities are perhaps the most important nodes in a network that also includes foundations, think tanks, and relatively hands-off government funding agencies.

Even societies like China, with its tradition of centralized state control, support a vigorous web of universities and institutes that produce and test ideas. In China, the government might drive the research agenda—rural educational outcomes, say, or international trade negotiations—but researchers are expected to produce rigorous results that stand up to outside scrutiny.

Not so in the Arab world. Despite a historic scholarly tradition, and a vigorous cohort of contemporary thinkers, the intellectual institutions in Arab countries are today almost universally subordinated to state control. As the dictators of the 1950s matured and grew stronger, they feared—correctly—that universities would nurture political dissent and that students were susceptible to free-thinking. (Even today, groups like the Muslim Brotherhood induct most of their leaders into politics through university student unions.) So they dispatched intelligence officers to control what professors taught, researched, and published, and to curtail student activism of a political flavor.

To the extent that think tanks, institutes, and journals were allowed to exist at all, they became either government mouthpieces or patronage sinecures. Plenty of individual scholars have continued to work in an independent vein, and many do research or publish work outside the influence of the ruling regime. For the most part, though, they do so abroad; those who speak openly in their home countries have often encountered gross repression, like the Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim, an establishment thinker who was imprisoned in 2000 for taking foreign grant money. His prosecution—despite his close ties to the ruling dictator’s family— served as a reminder to other scholars not to stray too far from the state’s goals.

The obstacles to researchers who hope to confront the region’s problems run even deeper than that: in most Arab nations, even basic data on public issues like water consumption, childhood education, and women’s health are treated as state secrets. So are government budgets, and anything to do with the military, the police, and industry. Egypt still tightly guards access to land registries running as far back as the Ottoman Era; Lebanon famously hasn’t conducted a census since 1932, and refuses to release any government data about the population size or its religious composition. International agencies like the World Bank are allowed to conduct surveys and research as part of development aid projects, but only on the condition that they keep the data confidential.

As a result, great Arab capitals like Damascus, Beirut, Baghdad, and Cairo, once among the world’s great centers of learning, have suffered a systematic impoverishment of intellectual life, especially in the realms in which it is now most needed.

***

IN MANY WAYS Seteney Shami’s career illuminates those challenges precisely. She left her native Jordan first for the American University of Beirut and then to earn an anthropology PhD from the University of California at Berkeley. Even as a young scholar, she knew she might face problems at home simply for writing about matters of identity among her own ethnic group, the minority Circassians, so she had her dissertation removed from public circulation. In the 1990s, she returned to the Middle East and built a well-regarded graduate program in anthropology at Jordan’s Yarmouk University—one of few rigorous graduate-level social sciences departments in the region. The experiment was short-lived, collapsing after only a few years when government patronage hires swamped the university faculty. Several scholars, including Shami, left.

She spent the next decade at US-funded foundations, working in Cairo for the Population Council and later in New York for the Social Science Research Council. She found that the scholars with whom she collaborated—and to whom she sometimes gave grants—relished the networks they built and the ideas that flowed when they had a chance to work with colleagues from different Arab countries, as well as in Europe and the United States. But there was a hitch: When the grant money ended, so did the network. In the West, such a change wouldn’t matter so much; the scholars would always have their home institutions to fall back on. Not so for a scholar in Jordan or Egypt, whose home institution might be far from supportive of his or her work.

“There is no institutional incentive to produce research in most Arab universities,” says Sari Hanafi, a sociologist at the American University of Beirut who is on the board of the new council. Hanafi conducted his own study of academic elites in the region, and discovered that most regional research was confined to safe descriptive projects—“production that will not question religious authority or the political system.” Essentially, it’s scholarship that doesn’t produce any new knowledge, or offer the possibility of change.

So a group of scholars including Shami and Hanafi began to conceive of something that would rectify the problem. Their vision isn’t a “think tank” in the Washington sense, but really almost a substitute for what universities do, creating a new and permanent forum to research, talk about, and solve serious social problems, outside government influence.

They secured funding from the Swedish government and later from Canada, the Carnegie Corporation, and the Ford Foundation. Among Arab countries, only Lebanon had laws that allowed a foreign international organization to operate free from government interference; even here, it took two full years for ACSS to clear all the red tape. In a way, the group’s timing was fortuitous: By the time the organization came online in 2011, with a few dozen scholars participating, the Arab uprisings were in full swing.

The first projects illustrate the flair ACSS is bringing to the sometimes stuffy world of social science. One study focuses on inequality, mobility, and development, and has brought together economists and other “hard” social scientists to explore issues like the impact of refugees from Syria’s civil war. A second, called “New Paradigms Factory,” unabashedly seeks to midwife the region’s next big ideas, asking scholars to challenge its dominant notions of sovereignty, national identity, and government power. The third major project, “Producing the Public in Arab Societies,” probes minority identity, community organizing, and alternative media sources—sensitive issues that governments steer away from, but that will be key to any new ordering of Arab civic life.

***

SOME AMONG the inaugural crop of researchers worry that despite its forward-looking visions, the window for an experiment like the Arab Council for the Social Sciences might already be closing. Two years ago, when Shami recruited her first team of scholars and grant recipients, a wave of optimism was washing over the Arab world. “It was a time to be brave, to test the boundaries of free expression,” she said.

Now, many of the same old restrictions have returned: Egyptian secret police, who had backed off after dictator Hosni Mubarak’s fall, resumed their open scrutiny of intellectuals after the military coup in July. Qatar, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates, fearing revolts from their own citizens, have also tightened their approach to academic inquiry, shutting down local research institutes and banning critical academics from attending conferences and teaching at international universities. Several of the scholars who met in Beirut as part of the “Producing the Public” working group declined to speak on the record even in general terms about the ACSS, fearing that any publicity at all might interfere with their work.

The first ACSS projects will take several years to yield results, and Shami says the long-term impact will depend, in part, on whether Arab governments continue to actively persecute intellectuals they perceive as critics. Meanwhile, Shami says, the group intends to go where it is most acutely needed—funding the edgiest and most relevant scholarship, and pushing for more open access to archives and data. To make up for the lack of regional peer-reviewed journals, it might begin publishing research itself. With the grandiose-sounding goal of transforming the entire discourse about the Arab world, Shami is aware that ACSS might fail; but she’s not interested, she said, “in biding our time and holding annual conferences.” If it proves necessary, she said, ACSS might create its own university.

Already, though, ACSS has had some visible impact. Omar Dahi, an economist at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, won a grant from the new council to study the way Syrian refugees are supporting themselves and how they are transforming the nations to which they’ve fled. He’s spending the semester in Beirut, and he expects to produce a series of articles that will bring rigor to a heated and topical policy debate. The council, he says, allows Arab scholars “to answer their own questions, and not only the questions being asked in North American and Western European academia.”

“It’s not easy, and ACSS alone is not going to be able to do it,” Dahi said. “But you have to start somewhere.”