How China Sees the World

My latest column in The Boston Globe:

The specter of a China with rising influence in the world has long provoked anxiety here in America. Like a speeding car that suddenly fills the rearview mirror, China has grown stronger and bolder and has done it quickly: Not only does it hold colossal amounts of American currency and boast a favorable trade deficit, it has increasingly been able to play the heavy with other nations. China is forging commercial relationships with African and Middle Eastern countries that can provide it natural resources, and has the clout to press its prerogatives in more local disputes with its Asian neighbors—including last week’s face-off with Vietnam in the South China Sea.

With China emerging more forcefully onto the world stage, understanding its foreign policy is becoming increasingly important. But what exactly is that policy, and how is it made?

As scholars look deeper into China’s approach to the world around it, what they are finding there is sometimes surprising. Rather than the veiled product of a centralized, disciplined Communist Party machine, Chinese policy is ever more complex and fluid—and shaped by a lively and very polarized internal debate with several competing power centers.

There’s a clear tug of war between hard-liners who favor a nationalist, even chauvinist stance and more globally minded thinkers who want China to tread lightly and integrate more smoothly into international regimes. And the Chinese public might be pushing a China-first mentality more than its leadership. Scholars believe that the boisterous nativism on display in China’s online forums appears to be a major factor pushing Chinese foreign policy in a more hard-line direction.

Today, for all its economic might, China still isn’t considered a global superpower. Its military doesn’t have worldwide reach, and its economy, while prolific, still hasn’t made the transition to producing technology rather than just goods for the world marketplace. Because of its sheer size and the dispatch with which it has moved from Third World economy to industrial powerhouse, however, China’s arrival as a power is considered inevitable.

As it does, understanding its foreign policy becomes only more important. Overall, the contours of its internal policy debates suggest a China that’s more isolated, unsure, and in transition than its often aggressive rhetoric would suggest. The candid discussion underway in China’s own public sphere underscores that China’s positions are still under negotiation. And one thing that emerges is a picture of a powerful state that is refreshingly direct in engaging questions about how to behave in the world as it embarks on what it fully expects will be China’s century.

Now What?

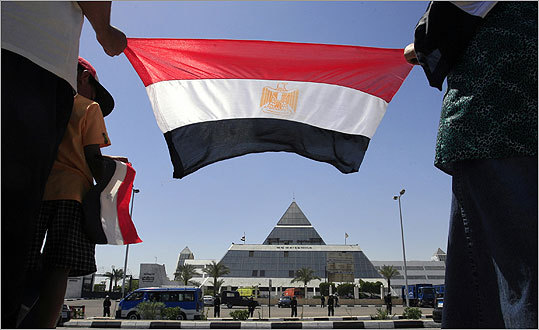

In The Boston Globe I write about the competing schools of thought over what Egypt’s next government should look like. This debate will only get more complicated as the year wears on, with different philosophies vying for predominance on the surface, while powerful and silent vested interests struggle for power below.

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”

Intelligent Design

Can spies do a better job predicting the future and understanding the present? A bunch of social science academics think so, and they’ve outlined a host of ways to fine-tune the American intelligence community’s notoriously jagged record of spotting chthonic trends in geopolitics. My latest column in The Boston Globe describes the movement by behavioralists to bring a little rigor to spying by, well, applying the scientific method.

The American intelligence system is the world’s most sophisticated surveillance network, costing $80 billion a year with 200,000 operatives covering the mapped world, but its work can read like a grand comedy of errors. Notwithstanding all the things America’s spies get right, it’s hard to ignore the unending parade of major, world-changing events that they missed. There was the failure to connect the warnings before 9/11; the false guarantee that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction; the assured stability of Arab autocrats up until this January.

In the last decade, the network has only continued to grow, with a key role in informing decisions of war and peace, and the near impossible task of preventing another terrorist attack on American soil. With so much at stake, you would assume the intelligence community rigorously tests its methods, constantly honing and adjusting how it goes about the inherently imprecise task of predicting the future in a secretive, constantly shifting world.

You’d be wrong.

In a field still deeply shaped by arcane traditions and turf wars, when it comes to assessing what actually works — and which tidbits of information make it into the president’s daily brief — politics and power struggles among the 17 different American intelligence agencies are just as likely as security concerns to rule the day.

What if the intelligence community started to apply the emerging tools of social science to its work? What if it began testing and refining its predictions to determine which of its techniques yield useful information, and which should be discarded? Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper, a retired Air Force general, has begun to invite this kind of thinking from the heart of the leviathan. He has asked outside experts to assess the intelligence community’s methods; at the same time, the government has begun directing some of its prodigious intelligence budget to academic research to explore pie-in-the-sky approaches to forecasting. All this effort is intended to transform America’s massive data-collection effort into much more accurate analysis and predictions.

“We still don’t really know what works and what doesn’t work,” said Baruch Fischhoff, a behavioral scientist at Carnegie Mellon University. “We say, put it to the test. The stakes are so high, how can you afford not to structure yourself for learning?”

End the Addiction to Stability

An obsession with “stability” — and an erroneous, narrow definition of the term — has warped American foreign policy, especially in the Middle East. Washington’s struggle to adjust to the rapid transformation of the region in part reflects a calcified mindset that for decades had to account for little change. Now, with the Arab political landscape barely recognizable, American policymakers are trying to adjust quickly. Imagine, American client regimes toppling one by one, while absolute monarchies in the Gulf are taking part in military interventions to unseat one dictator in Libya while propping up another in Bahrain. Some people will argue that all this turmoil amounts to an even stronger argument for stability; I’d say events suggest the opposite. That’s the subject of my latest Internationalist column in The Boston Globe.

America’s main goals in the Middle East have remained constant at least since the Carter years: We want a region in which oil flows as freely as possible, Israel is protected, and citizens enjoy basic human rights — or at least aren’t so unhappy that they begin to attack our interests.

In working toward these goals, the byword and the cornerstone of the entire venture has been stability. Washington has invested heavily — with money, weapons, and political cover — to guarantee the stability of supposedly friendly regimes in places like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. The idea is simple: A regime, even a distasteful and autocratic one, is more likely to help America, and even to treat its own people with a modicum of decency, if it doesn’t feel threatened. Instability creates insecurity, the thinking goes, and insecurity breeds danger.

But the unrest and dramatic changes of the past months are offering a very different lesson. An overemphasis on stability — and, perhaps, an erroneous definition of what “stability” even is — has begun harming, rather than helping, American interests in several current crisis spots. Our desire to keep a naval base in a stable Bahrain, for example, has allied us with the marginalized and increasingly radical Bahraini royal family, and even led us to acquiesce to a Saudi Arabian invasion of the tiny island to quell protests last month. To keep Syria stable, American policy has largely deferred to the existing Assad regime, supporting one of the nastiest despots in the region even as his troops have fired live ammunition at unarmed protesters. In a moral sense, this “stability first” policy has been putting America on the wrong side of the democratic transitions in one Arab country after another. And in the contest for pure influence, it is the more flexible approaches of other nations that seem to be gaining ground in such a fast-changing environment. If we’re serious about our goals in the Middle East, “stability” is looking less and less like the right way to achieve them.

Foreign policy shifts slowly, and it’s hard to replace such a familiar, if flawed, approach to the world. But recent events have strengthened the ranks of thinkers who argue that there may be more effective and less costly ways to press our interests in the Middle East. We could take an arm’s length approach, allowing that not every turn of the screw in the Middle East amounts to a core national interest for the United States — in effect, abstaining from some of the region’s conflicts so we have more credibility when we do intervene. We could embrace a more dynamic slate of alliances that allows the United States to shift its support as regimes evolve or decay. Finally, we could redefine stability entirely and downgrade it as a priority, so that we recognize its value as simply one of many avenues toward achieving US interests.

Read the rest in The Boston Globe.

Some Lessons of the Arab Revolts

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I explore some of the implications of the Arab revolutions for US policy. It will take a long time for American policy makers to grasp the implications of the popular wave sweeping the Arab world, and if history is any guide, the architects of American policy might never actually figure out what happened, why, and how best to respond. One of my favorite analysts and bloggers, Issandr El Amrani at The Arabist, thinks the arguments I make are at best banal, at worst, completely wrong-headed.

Here’s how the column opens:

The popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and beyond have seized the world imagination like no events since the collapse of the Iron Curtain. Regimes are teetering, dictators have fallen, and unexpected coalitions have managed to conjure street-level power seemingly out of thin air. Tunisians took credit for Egypt’s revolution; Egyptian demonstrators in turn claim they inspired people in Wisconsin and Bahrain.

Much remains uncertain, and even the most experienced observers have no idea who will hold power in the aftermath of these uprisings. But already we’ve learned more in a few short months than we gleaned from decades of careful study about the real power base of Moammar Khadafy and Hosni Mubarak, about the balance among armies and tribes, about the relative power of secular and Islamist activists. We’re seeing the true measure of oil money and the Muslim Brotherhood, of popular anger about corruption, and of the real interest in economic liberalization.

But perhaps the most surprising lessons emerging from all the unrest are even bigger ones — insights that extend well beyond the Middle East, and are forcing thinkers and policy makers to reconsider some basic assumptions that have long guided America’s foreign policy. How much impact can America really have on world events? How do our alliances function at crucial moments? Who really has the potential to initiate and control massive change in modern societies? The surprising answers suggested by the Arab revolts might create new options in the minds of American policy makers looking to advance not only US security and economic goals, but also the causes of human rights, transparency, and democratic governance.

A Comeback for Isolationism?

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I write about a group of critics I think of as “new isolationists” — cosmopolitan and balanced advocates for a modest, demilitarized, less interventionist American foreign policy. They’re urbane, they care about the world, but they think America meddles far too much — a level of interference that hurts America as much as the rest of the world.

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I write about a group of critics I think of as “new isolationists” — cosmopolitan and balanced advocates for a modest, demilitarized, less interventionist American foreign policy. They’re urbane, they care about the world, but they think America meddles far too much — a level of interference that hurts America as much as the rest of the world.

These old-school realists come at the question from different perspectives but they all share in common a willingness to challenge the received wisdom about America’s approach to the world, and to question whether militaristic interventionism objectively has helped or harmed America’s economy and security. Their critique has matured in the decade since 9/11, and the time is ripe, I think, for us to reconsider their arguments.

There are few ways to get Democrats and Republicans to agree faster than by bringing up national security. Should America invest in a dominant, high-tech military? Should it spend time, treasure, and lives intervening in distant lands and protecting allies? Almost always, the short answer is a resounding yes. Ever since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt browbeat the skeptics and brought America into the Second World War, the country’s foreign policy has been robustly — some would say aggressively — interventionist.

Disagreements have flared only over the details: where to intervene and with what tools. Especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, both right and left took for granted America’s position as lone superpower — and that securing America required complex engagements in global conflicts. There’s mainly a difference in tone between “liberal order building,” Princeton grand strategist G. John Ikenberry’s proposal for how America should reestablish its global position, and conservative historian Robert Kagan’s unapologetic demand for American “primacy.”

This consensus in the world’s leading economy has underwritten an unparalleled military that can strike anywhere in the world. The United States has invested trillions of dollars in projecting power, and immeasurable amounts of political capital fulfilling what it considers its rightful, if exhausting, role. Its policy makers have assumed that America must police disputes from the Straits of Taiwan to the Straits of Hormuz. The next 10 largest militaries combined do not equal America’s in size, expense, or power.

But all that glitter obscures a glaring failure, according to an increasingly energized phalanx of critics. While their prescriptions vary, they all believe America suffers from imperial overreach, fighting abroad to the detriment of prosperity at home. MIT’s Barry Posen has been developing “the case for restraint,” calling for the “stingy” use of military power. Boston University historian Andrew Bacevich argues in his latest book, “Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War,” that America has become a national security state addicted to military interventions that justify its vast defense apparatus. And the University of Chicago’s John Mearsheimer, in the latest issue of the National Interest, charges that American interventionism creates more threats than it neutralizes. They, and a handful of other thinkers, say that America needs to stop meddling far and wide and concentrate on its forgotten, core interests — if it is not already too late. “The results have been disastrous,” says Mearsheimer.

No Big Deal

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

My latest column in The Boston Globe explores the alternative to sweeping international agreements: little incremental solutions that might, in fact, do better at addressing the world’s ills.

The great international problems of our time beggar the imagination: global warming, pandemics, war crimes, nuclear proliferation, just to name a few. Their complexity confounds the most agile of technocrats, and the stakes involved are high, affecting billions of people living under every sort of government.

For half a century, the conventional approach to these problems has been to build massive international treaties. Intricate worldwide problems demand an integrated approach — a grand bargain, so to speak, that addresses all the winners and losers in a single, encompassing agreement.

This is the animating assumption behind the world’s approach to global warming, for example. To persuade growing nations like China to limit their consumption of fossil fuels, the thinking goes, the world needs a comprehensive framework ensuring that more developed nations make equivalent sacrifices. The climate is simply too large a problem to address piecemeal, or by tinkering with minor symptoms.

But what if this approach results in less progress? What if more modest agreements — on climate change, loose nukes, and other sweeping problems — would yield better results than a long, noble quest for a grand bargain?

Talk to Terrorists

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

The Internationalist, my new monthly column about foreign affairs, debuted today in The Boston Globe Ideas section. The opening column explores the views of a cohort I call “engagement hawks,” who offer a pragmatic, utilitarian critique of the traditional argument that negotiating with terrorists makes us weaker. These thinkers and practitioners have articulated an intellectual critique of America’s historical position, and have tried to extract lessons from America’s sometimes-bumbling experiences since the Cold War reconciling — or trying and failing to do so — with enemies it has labeled “terrorists.”

Ronald Reagan framed the debate over whether to talk to terrorists in terms that still dominate the debate today. “America will never make concessions to terrorists. To do so would only invite more terrorism,” Reagan said in 1985. “Once we head down that path there would be no end to it, no end to the suffering of innocent people, no end to the bloody ransom all civilized nations must pay.”

America, officially at least, doesn’t negotiate with terrorists: a blanket ban driven by moral outrage and enshrined in United States policy. Most government officials are prohibited from meeting with members of groups on the State Department’s foreign terrorist organization list. Intelligence operatives are discouraged from direct contact with terrorists, even for the purpose of gathering information.

President Clinton was roundly attacked when diplomats met with the Taliban in the 1990s. President George W. Bush was accused of appeasement when his administration approached Sunni insurgents in Iraq. Enraged detractors invoked Munich and ridiculed presidential candidate Barack Obama when he said he would meet Iran and other American adversaries “without preconditions.” The only proper time to talk to terrorists is after they’ve been destroyed, this thinking goes; any retreat from the maximalist position will cost America dearly.

Now, however, an increasingly assertive group of “engagement hawks” — a group of professional diplomats, military officers, and academics — is arguing that a mindless, macho refusal to engage might be causing as much harm as terrorism itself. Brushing off dialogue with killers might look tough, they say, but it is dangerously naive, and betrays an alarming ignorance of how, historically, intractable conflicts have actually been resolved. And today, after a decade of war against stateless terrorists that has claimed thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of foreign lives, and cost trillions of dollars, it’s all the more important that we choose the most effective methods over the ones that play on easy emotions.