End of the Athens Ghetto

A welcome casualty of Greece’s economic meltdown: the most grating exemplar of the cafe-entitlement culture in my neighborhood. Ghetto Luxury Lounge opened around the turn of the millennium, peddling overpriced tequila sunrises and iced cappuccinos to a clientele whose aspirations appeared strangled in their skinny jeans. This weekend I noticed the “For Rent” sign on Ghetto with a jolt of pleasure as sweet and nasty as the drinks it used to serve. Along with all the unwelcome dislocation of the Greek economic crisis, at least we can look forward to a little weeding.

How China Sees the World

My latest column in The Boston Globe:

The specter of a China with rising influence in the world has long provoked anxiety here in America. Like a speeding car that suddenly fills the rearview mirror, China has grown stronger and bolder and has done it quickly: Not only does it hold colossal amounts of American currency and boast a favorable trade deficit, it has increasingly been able to play the heavy with other nations. China is forging commercial relationships with African and Middle Eastern countries that can provide it natural resources, and has the clout to press its prerogatives in more local disputes with its Asian neighbors—including last week’s face-off with Vietnam in the South China Sea.

With China emerging more forcefully onto the world stage, understanding its foreign policy is becoming increasingly important. But what exactly is that policy, and how is it made?

As scholars look deeper into China’s approach to the world around it, what they are finding there is sometimes surprising. Rather than the veiled product of a centralized, disciplined Communist Party machine, Chinese policy is ever more complex and fluid—and shaped by a lively and very polarized internal debate with several competing power centers.

There’s a clear tug of war between hard-liners who favor a nationalist, even chauvinist stance and more globally minded thinkers who want China to tread lightly and integrate more smoothly into international regimes. And the Chinese public might be pushing a China-first mentality more than its leadership. Scholars believe that the boisterous nativism on display in China’s online forums appears to be a major factor pushing Chinese foreign policy in a more hard-line direction.

Today, for all its economic might, China still isn’t considered a global superpower. Its military doesn’t have worldwide reach, and its economy, while prolific, still hasn’t made the transition to producing technology rather than just goods for the world marketplace. Because of its sheer size and the dispatch with which it has moved from Third World economy to industrial powerhouse, however, China’s arrival as a power is considered inevitable.

As it does, understanding its foreign policy becomes only more important. Overall, the contours of its internal policy debates suggest a China that’s more isolated, unsure, and in transition than its often aggressive rhetoric would suggest. The candid discussion underway in China’s own public sphere underscores that China’s positions are still under negotiation. And one thing that emerges is a picture of a powerful state that is refreshingly direct in engaging questions about how to behave in the world as it embarks on what it fully expects will be China’s century.

Discouraging Lessons of History

CAIRO, Egypt — Old ways die hard.

It only requires a quick glance at the new Egyptian junta — as most of the country’s citizens see it — to understand how the military rulers see their inviolable position. On its Facebook page, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces issues terse directives. Egyptian citizens post comments by the tens of the thousands, but there’s never any response. The military’s high-handed public outreach is similarly one-sided. One general appears on television to read the same directives, stony-faced, to a camera. And every now and again, the military stages public “dialogues,” which come across, intentionally or not, as patronizing lectures.

How does the military view its future in Egypt? What internal dynamics are shaping the military’s political strategy, which could in large part determine whether February’s revolution is a success? Within the officer corps, there are diverse views as to how much power the Egyptian army should wield, and how much it should yield to elected civilians.

It can be difficult to get answers to these questions from the military, perhaps in part because they themselves don’t yet know. So I’ve turned to reading history, hoping to find answers there, and was struck once again by the tight congruity between present-day Egypt and the critical points it has experienced over the last century and a half. During much of that time, Egypt has politically lain fallow, either because of self-induced paralysis as during Hosni Mubarak’s rule or long periods of colonial subjugation, as during the era of the British-orchestrated Veiled Protectorate.

Indignant at Syntagma: Tahrir Comes to Athens

Inspired by Egyptians and spurred to action by Spaniards, the Greek people have taken over their capital’s central square to demand, simply, an end to corruption, consumerism, and their nation’s long, self-induced economic immolation. Now that Greece has committed hara-kiri, its citizens can point to other culprits, like bureaucrats from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund who erroneously prescribe austerity at the inflection point of a depression.

Set aside the political economy for a moment, and behold the pop culture of protest. Syntagma Square looks like Tahrir with beer, franks, and port-a-potties. And, oh, not nearly so many people.

Set aside the political economy for a moment, and behold the pop culture of protest. Syntagma Square looks like Tahrir with beer, franks, and port-a-potties. And, oh, not nearly so many people.

Yesterday on an evening tour of the tent city I encountered a drumming circle, some stoners playing the guitar; immigrants rights activists; labor organizers planning the nationwide general strike called for this Tuesday; legions of beer salesmen; a pair of dueling end-of-the-world-is-nigh prophets; a row of sausage salesmen without any customers; representative of NGOs for the homeless, the environment, and other worthy causes; and curious passers-by on their way to the metro entrance.

Supporters rally at the Facebook page “Indignant in Syntagma,” and the rest of Athens plans their days by consulting a student-run page which lists all the strikes that disrupt life in the capital.

Banners declare “The quiet citizen is a useless citizen” and “We are peaceful.” Speechifiers spoke of IMF ineptitude, government failure, and the imperative for labor solidarity on the day of the general strike. “The nation must come to a halt,” a said without any inflection over a megaphone.

Banners declare “The quiet citizen is a useless citizen” and “We are peaceful.” Speechifiers spoke of IMF ineptitude, government failure, and the imperative for labor solidarity on the day of the general strike. “The nation must come to a halt,” a said without any inflection over a megaphone.

The popular grievances are legitimate, of course: the tax scofflaws, union maximalists, over-leveraged materialists, and greedy politicians who ruined the country over the course of 37 years probably include only about half the citizenry. The remainder are justifiably upset that their economic prospects have been doomed as well. Of course, it’s unclear which half is represented in Syntagma Square. But it is clear that they’re peaceful, well-fed, and not likely anytime soon to face a shortage of nicely chilled Mythos Beer.

UPDATE: Today organizers are hoping to bring 1 million people out to the center of Athens. The mass protest is meant to start at 6 p.m., by which time I hope to be sailing away from the mainland, so I’ll have to learn from afar how it goes.

Muslim Brotherhood goes legal

My latest column in The Atlantic considers the turning point reached this week when the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party gained official recognition.

CAIRO, Egypt — This Tueday, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood became a legal political party for the first time since President Gamal Abdel Nasser banned it more than half-a-century ago. The military officers managing Egypt’s transition out of the Age of Mubarak approved the Brotherhood’s new Freedom and Justice Party, the Islamist organization’s chosen vehicle to political power.

After decades in limbo, the Muslim Brotherhood will now have all the benefits of unambiguous legal status — and face all the scrutiny and questioning to which a political behemoth is subjected. The Brotherhood has built its considerable following, and honed its impressive organizational wherewithal, by striving in the shadows against a police state’s full force.

During their decades under the ban, Brothers spread their religious message and delivered what services they could. Now, however, the challenges are vast and political, and the underground methods of a doctrinaire religious group (whose primary mission, always, was spreading a strict message of faith) won’t play the same way on the political stage.

It’s a confusing transition for the Islamist activists trying to reposition their organization from oppressed social group to political strongman.

Egypt on the John Batchelor show

John Batchelor asks me about Egypt’s constitutional debate on his show; clip starts just after the 19:00 mark.

The Revolution Pushes On

CAIRO, Egypt — The Egyptian uprising that began on January 25 has yet to reach its zenith. Many an acerbic observer has noted that so far it has yielded little more than a personnel change in a military dictatorship. That same cynicism, of course, misled many Egypt-watchers when the protests first began, discount the potential of people power to force change. Oddly, the same demerits summoned then are now cited as proof that Egypt has not really witnessed a revolution or that its revolution is in disarray. The main allegations: the popular movement against the regime lacks a leader and a coherent plant; it relies too much on elites; its criticisms of the military will alienate most Egyptians, who just seek stability; and that the military is more firmly entrenched in power than ever before.

Consider the significance of Friday, when one of the largest protests in Tahrir in months drew the full, preemptory wrath not only of the military junta, but of the Muslim Brotherhood. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, or SCAF, addressing the multitudes in the traditional intimidating rhetoric of Egypt’s ruling class but through the modern vehicle of its Facebook page, warned about “suspicious forces conducting acts that will cause tension between the Egyptian people and the armed forces.” Several activists, including a trio of artists, had been arrested the week before while promoting the march, and the military ominously warned it would stay away from Tahrir, and that thugs might run rampant. This last declaration was taken as a hint that the military might be reviving one of the regime’s oldest tricks, pulling security off the street and then deploying its own paid baltagaya to beat and harass dissidents.

For its part, the Brotherhood, the only formidable political organization outside the state, has shown itself cynically willing to play footsie with the junta while discrediting its erstwhile revolutionary confreres. “At whom is the anger directed?” the Brotherhood leadership asked in a patronizing statement in which it explained why it would boycott the May 27 Tahrir protest, which it viewed as an unacceptable rebuke toward the military — or what it considers the unassailable sentiments of the “majority” of the Egyptian people.

These are old tropes, echoing a favored ploy of Mubarak, his predecessors, and many of his surviving colleagues in the fraternity of Arab dictators: if you want stability, behave and do as we tell you — otherwise, drown in chaos.

The youth leaders who galvanized the May 27 protest are anything but uniform or centrally organized. They included leftists, socialists, nationalists, and Islamists. The only thing they shared in common is a belief that mass protests have proven the only effective tool in winning concessions from the SCAF. Beyond that, their platforms and styles diverge. Leaders of the April 6 youth group are concentrating on a program of public outreach to convince Egyptians that only an end to de facto military rule can save the economy and their livelihoods. Many of the liberals have their eyes on upcoming elections, and are jockeying their newly formed parties for position, or arguing about the correct order for a transition: elections first, then a constitution, as the military suggests? Or vice versa? Muslim Brotherhood youth leaders brought out hundreds of their own members in solidarity and to tell their own leaders that the organization cannot function internally as a dictatorship.

Gaping questions face the revolutionary movement going forward. Can it force the military to back down on current practices that include censoring the media, trying civilians in military courts, drawing the rules for elections and political party formation by fiat, all while allowing the police to stay home and the economy to drift?

Now What?

In The Boston Globe I write about the competing schools of thought over what Egypt’s next government should look like. This debate will only get more complicated as the year wears on, with different philosophies vying for predominance on the surface, while powerful and silent vested interests struggle for power below.

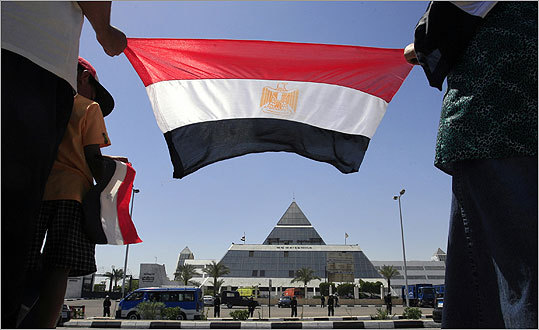

CAIRO — Traffic stopped in Tahrir Square during the revolution, but four months later, the torrent of marching humans that briefly made Cairo a world symbol of the thirst for justice has been replaced by the familiar, endless stream of grumbling cars.

The tricolor paint on the city’s trees, applied with gusto in the immediate weeks after President Hosni Mubarak resigned, has already begun to fade. As the wilting heat approaches its summertime averages in the 90s, vendors here do a brisk business selling “I [heart] Egypt” T-shirts, mock license plates commemorating the date of the uprising, and posters of the young martyrs to Mubarak’s security forces.

Schools have reopened; births and deaths are once again registered by Egypt’s ubiquitous bureaucracy; and the machinery of state continues to deliver the basic services that make this nation of 80 million function. The military junta that replaced Mubarak polices the streets and censors the media, though with a touch slightly lighter than Mubarak’s. There are still street demonstrations; on most Fridays, small factions chant in Tahrir Square and distribute leaflets demanding to put figures of the old regime on trial, fix the broken economy, or allow greater freedom to criticize the government.

Most of the nation’s energy, however, has shifted to a new debate: what should come next. Egyptians are realizing that they now face a challenge perhaps even more historic than its revolution. They need to design, nearly from scratch, a legitimate state to govern the most populous Arab nation in the world.

Egyptians are supposed to write a new constitution sometime this fall. And although no one is sure precisely how this will occur — the schedule is controlled by the military junta, which communicates chiefly through updates on its Facebook page — the public conversation has already metamorphosed into raging debate over what the government should look like. The outpouring of public frustration that reached a crescendo in Tahrir Square on Feb. 11 has now moved onto a crowded lineup of television talk shows and the cafes. As youth activist Ahmed Maher put it over a demitasse at the Coffee Bean this week: “Before the revolution, everyone talked about soccer and drugs. Now they talk only about politics.”

Egypt’s Socialist Media Scene

That’s right, not social media, which is all the rage among the global cognoscenti, but socialist media.

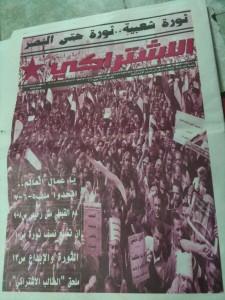

Egypt’s small but dedicated Center for Socialist Studies (a think-tank-like organization that’s hoping to create a Workers Democratic Party) has been reconsidering its approach since the January 25 revolution here. At a meeting on Tuesday night, a core group of about a dozen movement activists debated the party’s media strategy. It was but one of many manifestations of the flowering of political activism across Egypt; on this night alone, dozens of youth movements of different stripes were holding similar meetings.

The latest issue features a distorted and colorized crowd shot from Tahrir Square, with the tagline “Popular Revolution … Revolution Until Victory.” The table of contents leads with a section called “Workers of the world unite,” which can can be round on pages 5 through 7.

“We have to reach the people using the same tools as the government and the upper-class media: television and Facebook,” said Ibrahim AlSahary, a journalist whose passion is socialism. He believes that class warfare between officers and enlisted men will ultimately hobble Egypt’s military rulers and open the way for civil rule – and he thinks socialists can foment that division.

Another journalist, Bisan Kassab, fought to get a word in edgewise during Ibrahim’s discursive flights of oratory, tailored more for a parliamentary chamber than the austere meeting room near Giza Square.

“Most people don’t believe in class warfare,” she said. “We need to talk about things people care about, in language people can understand.” Bisan also wanted the meeting to deal with its actual agenda. The Socialist, she pointed out, was unreadable, its bleak layout showcasing tendentious articles about abstract socialist theory. Couldn’t the paper publish engaging feature articles, and cover news that’s actually happening?

“People want to be informed,” she said. “Let’s inform them.”

“People want to be informed,” she said. “Let’s inform them.”

An American socialist who writes for the International Socialist Worker, nodded approvingly. “This is the beginning of the revolution,” he observed.

Ahmed Shalabi, 27, an unemployed newcomer to the Socialist Party ranks, quivered with excitement. He wore a polo shirt with horizontal purple stripes and colored eyeglass frames; several people in the room mistook him for a precocious teenager. He had been distributing his own tracts in Tahrir Square a few weeks ago when he meet Ibrahim, and he found the socialist platform simpatico. He already had submitted several pieces to the newspaper’s editor and was dismayed to have received no response.

“People have been sleeping, almost dead for thirty years,” Ahmed said, in his high, almost sing-song, voice. He wants the paper to write about abuses of authority by the military, and its continuing rule under an exceptional state of emergency.

“People my age want our voices heard. We don’t understand what you mean when you talk about counter-revolution, because your language is too complicated,” he said. “We can’t just talk to our friends.”

The Shiny New Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brothers hosted their grand coming-out party on Saturday night. Officially, the occasion marked the opening of their new headquarters, a seven-story monstrosity that looks like an egg-cream ziggurat on a breezy plateau above Islamic Cairo. Unofficially, the event was a declaration that the Brothers have arrived and will be kingmakers during Egypt’s season of political change.

“We’re not banned anymore,” exulted Mohsen Radi, who served a turn in parliament as a representative of a Delta town called Banha. “By the grace of freedom, by the grace of the revolution, we have regained our place.”

As symbols go, the building and its inaugural could not have been more potent. For decades, the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide operated out of a stuffy, dark, low-ceilinged apartment on the isle of Manial, in Cairo’s center. A team of state security men loitered out front. Entering visitors had to clamber over the pile of shoes in the hallway, between the elevator and the door. Senior officials would conduct interviews in the corner of the same room where the rest of the leadership was deliberating.

It was, to say the least, a no-frills operation, highlighting the Brotherhood’s ambiguous status as a legally prohibited but semi-tolerated organization.

Between 2005 and 2009, when the Brothers held 88 parliamentary seats, the organization opened a slightly more spacious parliamentary office nearby. State security forbade them from organizing any large public events, and even their annual Ramadan iftaar was cancelled. During functions there, the power often mysteriously cut out, with a frequency that the Brotherhood accepted as one of the more petty manifestations of state harassment.

Now, however, the Brotherhood is freely exercising its organizational muscle. Since Mubarak was run out of office, the Muslim Brotherhood has opened offices in every province. It is launching its own satellite television network. It has entered coalition talks with other groups, and has founded its own political party, called Freedom and Justice, which has a Christian vice president. At first, in an effort to comfort worried Christians and secularists, the Brotherhood said it would contest only 30 percent of the seats in parliament, and wouldn’t run a presidential candidate. Last week, it raised the ante, now saying it will compete for half the parliamentary districts.

With the opening of the new official headquarters in Moqattam, the transformation is complete. Bright lights illuminate the party logo in English and Arabic – a pair of green crossed swords.

About a hundred movement activists prayed outside before the official opening on Saturday night (the building’s been in use for weeks already). They chanted the Brotherhood motto in unison:

God is great.

The Prophet is our teacher.

The Koran is our constitution.

Jihad is our way.

Martyrdom is our goal.

Then they stormed into the building and emptied trays of fruit juice.

In a sign of the Brotherhood’s political heft, a parade of notables came to pay respects, including presidential front-runner and former Arab League chief Amr Moussa and a coterie of other secular politicians and judges.

In a rear lot behind the headquarters, more than a thousand supporters assembled in a dirt lot covered with carpets for the occasion. A band sang paeans to freedom, brotherhood, and the Brotherhood.

Khairat Shater, a millionaire and number-two official in the Brotherhood credited with being one of its most powerful fixers, grinned just beside the stage.

“Where do you think state security is now?” I asked. At the last Brotherhood function I attended, an iftaar in the parliamentary offices in August, the number of plainclothes intelligence officers hovering around the event equaled that of the Brotherhood officials inside.

“They haven’t gone home,” he said. “They’re around here somewhere.”

If one were keeping score, however, the Brotherhood would look to be ahead.

How Obama Played in Cairo

Obama’s speech was not all the rage in Cairo today. Many of the youth activists I know weren’t even planning to watch the speech. The US embassy organized a viewing party in a downtown hotel ballroom, drawing just over a hundred Egyptians.

“It’s a little late, but I think Obama is finally trying to get on the right side of history,” said Heba Ghannam, who pays her rent working as a corporate marketer but exercises her passion for politics by tweeting, as she did throughout the speech.

As far as Egypt is concerned, Heba wants one thing from Washington: pressure on the Egyptian army to back out of politics rather than consolidate a “soft dictatorship.” Nothing in the speech convinced her that Obama planned to put muscular American pressure on the generals who still run Egypt.

With this crowd, the president had only two applause lines (which I discussed today on Here & Now with Fawaz Gerges). His declaration that the United States would forgive a democratizing Egypt’s debts drew tepid clapping. His endorsement of Palestinian borders based on the 1967 line sparked thunderous noise and catcalls.

After a few seconds, though, the crowd returned to its staid, if mildly cheerful, pose.

“No surprises. I liked the tone,” said Nagham Osman, a 30-year-old film director.

An embassy worker standing in the back of the room nodded with satisfaction, following the running commentary of his friends on his smart phone.

“Nothing is guaranteed,” he said with a shrug. “We need to see actions.”

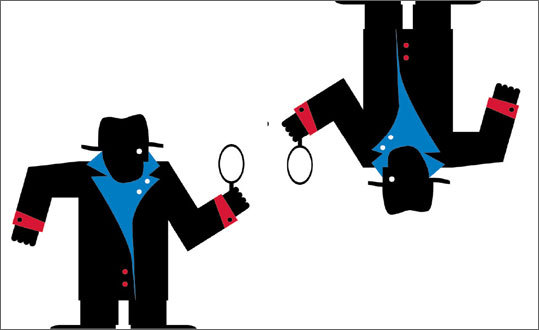

Intelligent Design

Can spies do a better job predicting the future and understanding the present? A bunch of social science academics think so, and they’ve outlined a host of ways to fine-tune the American intelligence community’s notoriously jagged record of spotting chthonic trends in geopolitics. My latest column in The Boston Globe describes the movement by behavioralists to bring a little rigor to spying by, well, applying the scientific method.

The American intelligence system is the world’s most sophisticated surveillance network, costing $80 billion a year with 200,000 operatives covering the mapped world, but its work can read like a grand comedy of errors. Notwithstanding all the things America’s spies get right, it’s hard to ignore the unending parade of major, world-changing events that they missed. There was the failure to connect the warnings before 9/11; the false guarantee that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction; the assured stability of Arab autocrats up until this January.

In the last decade, the network has only continued to grow, with a key role in informing decisions of war and peace, and the near impossible task of preventing another terrorist attack on American soil. With so much at stake, you would assume the intelligence community rigorously tests its methods, constantly honing and adjusting how it goes about the inherently imprecise task of predicting the future in a secretive, constantly shifting world.

You’d be wrong.

In a field still deeply shaped by arcane traditions and turf wars, when it comes to assessing what actually works — and which tidbits of information make it into the president’s daily brief — politics and power struggles among the 17 different American intelligence agencies are just as likely as security concerns to rule the day.

What if the intelligence community started to apply the emerging tools of social science to its work? What if it began testing and refining its predictions to determine which of its techniques yield useful information, and which should be discarded? Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper, a retired Air Force general, has begun to invite this kind of thinking from the heart of the leviathan. He has asked outside experts to assess the intelligence community’s methods; at the same time, the government has begun directing some of its prodigious intelligence budget to academic research to explore pie-in-the-sky approaches to forecasting. All this effort is intended to transform America’s massive data-collection effort into much more accurate analysis and predictions.

“We still don’t really know what works and what doesn’t work,” said Baruch Fischhoff, a behavioral scientist at Carnegie Mellon University. “We say, put it to the test. The stakes are so high, how can you afford not to structure yourself for learning?”

RIP

Many people have put together wonderful tributes to Tim Hetherington and to our friend Chris Hondros, killed yesterday in Libya. Chris was not only a great photographer but also a good man, with reservoirs of humility. He had a surprising interest in teaching his craft to others and explaining the stories he felt compelled to cover to audiences back home. When I think of his photographs, I first think about the spirit with which he worked, his warm Southern greeting and his ready hug. The first image that comes to mind – if only for its impact – is of the girl outside Mosul, just orphaned by American soldiers at a checkpoint.

Take a close look at the work of these two war reporters. With their deaths, we have lost far more than just two souls.

– “Diary,” Tim Hetherington’s haunting recent film about the dislocation of working in war zones and in New York City.

– Chris Hondros’ last file for Getty

– Some retrospectives of their work on the Lens Blog (Tim, Chris), and elsewhere.

End the Addiction to Stability

An obsession with “stability” — and an erroneous, narrow definition of the term — has warped American foreign policy, especially in the Middle East. Washington’s struggle to adjust to the rapid transformation of the region in part reflects a calcified mindset that for decades had to account for little change. Now, with the Arab political landscape barely recognizable, American policymakers are trying to adjust quickly. Imagine, American client regimes toppling one by one, while absolute monarchies in the Gulf are taking part in military interventions to unseat one dictator in Libya while propping up another in Bahrain. Some people will argue that all this turmoil amounts to an even stronger argument for stability; I’d say events suggest the opposite. That’s the subject of my latest Internationalist column in The Boston Globe.

America’s main goals in the Middle East have remained constant at least since the Carter years: We want a region in which oil flows as freely as possible, Israel is protected, and citizens enjoy basic human rights — or at least aren’t so unhappy that they begin to attack our interests.

In working toward these goals, the byword and the cornerstone of the entire venture has been stability. Washington has invested heavily — with money, weapons, and political cover — to guarantee the stability of supposedly friendly regimes in places like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. The idea is simple: A regime, even a distasteful and autocratic one, is more likely to help America, and even to treat its own people with a modicum of decency, if it doesn’t feel threatened. Instability creates insecurity, the thinking goes, and insecurity breeds danger.

But the unrest and dramatic changes of the past months are offering a very different lesson. An overemphasis on stability — and, perhaps, an erroneous definition of what “stability” even is — has begun harming, rather than helping, American interests in several current crisis spots. Our desire to keep a naval base in a stable Bahrain, for example, has allied us with the marginalized and increasingly radical Bahraini royal family, and even led us to acquiesce to a Saudi Arabian invasion of the tiny island to quell protests last month. To keep Syria stable, American policy has largely deferred to the existing Assad regime, supporting one of the nastiest despots in the region even as his troops have fired live ammunition at unarmed protesters. In a moral sense, this “stability first” policy has been putting America on the wrong side of the democratic transitions in one Arab country after another. And in the contest for pure influence, it is the more flexible approaches of other nations that seem to be gaining ground in such a fast-changing environment. If we’re serious about our goals in the Middle East, “stability” is looking less and less like the right way to achieve them.

Foreign policy shifts slowly, and it’s hard to replace such a familiar, if flawed, approach to the world. But recent events have strengthened the ranks of thinkers who argue that there may be more effective and less costly ways to press our interests in the Middle East. We could take an arm’s length approach, allowing that not every turn of the screw in the Middle East amounts to a core national interest for the United States — in effect, abstaining from some of the region’s conflicts so we have more credibility when we do intervene. We could embrace a more dynamic slate of alliances that allows the United States to shift its support as regimes evolve or decay. Finally, we could redefine stability entirely and downgrade it as a priority, so that we recognize its value as simply one of many avenues toward achieving US interests.

Read the rest in The Boston Globe.

Michael Hanna on Egypt

Michael Hanna at The Century Foundation has a smart oped in The Christian Science Monitor about the steps necessary to translate Egypt’s revolution into lasting reforms. He argues that the rushed timeline imposed by the military might thwart the systemic changes needed to institute a credible constitution and initiate electoral politics.

Michael Hanna at The Century Foundation has a smart oped in The Christian Science Monitor about the steps necessary to translate Egypt’s revolution into lasting reforms. He argues that the rushed timeline imposed by the military might thwart the systemic changes needed to institute a credible constitution and initiate electoral politics.

Progress based solely on a hasty electoral transition would be an illusion – which might undercut efforts at real reform. Instead of accepting a transition process implemented and dictated solely by the armed forces,Egypt’s opposition should remain united in seeking immediate actions that will preclude diversion to military-led governance, while allowing for a more realistic transitional period.

The country’s opposition groups are keen to ensure that the armed force’s custodianship is, in fact, temporary, and not a prelude to consolidation of a revamped, military-led regime. This concern – and broader and well-justified concerns about a counter-revolution – are understandable based on Egypt’s history and recent developments. Yet, these very same concerns could lead to support for a transition process that will actually undermine the core goals of the Egyptian uprising and subvert thorough reform. A six-month timetable for popular elections, as was announced by the Egyptian military, will dictate that reform in the interim period will be shallow and that even free and fair elections will not be an opportunity for true representational politics. Read the rest here.

We had a panel discussion at The Century Foundation last week where we discussed some of the implications of the revolution for Egypt going forward and for the Arab world as a whole. My favorite part of the evening came when the Yemeni ambassador to the U.N. Abdullah Al-Saidi diagnosed the central problem of the region as “leaders who have tried to transform republics into monarchies” — a malady from which he did not exempt his own country (you can watch the q & a here). That’s a fair enough way to summarize the ills of regimes in Yemen, Egypt, Libya, and Syria. It doesn’t address the failure to govern, which is at root what plagues all the Arab states, including those that are avowedly hereditary monarchies (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco). You can watch the event at The Century Foundation here.

Resistance and Revolution

In the weeks since I returned from Egypt, I’ve made a number of previously scheduled talks, originally intended to cover Hezbollah and the most recent developments in Lebanon. I’ve made a stab at addressing the tumultuous change more broadly, as three forces are now competing for popular momentum: revolution (the massive and ongoing regional wave), reaction (the old statist regimes and monarchs), and resistance (the axis of empowerment through armed uprising).

It appears that Salve Regina, the small college in Newport, R.I. that hosted one of those talks, has posted the video online. It is with some trepidation that I post the link.

Some Lessons of the Arab Revolts

In my latest Internationalist column for The Boston Globe, I explore some of the implications of the Arab revolutions for US policy. It will take a long time for American policy makers to grasp the implications of the popular wave sweeping the Arab world, and if history is any guide, the architects of American policy might never actually figure out what happened, why, and how best to respond. One of my favorite analysts and bloggers, Issandr El Amrani at The Arabist, thinks the arguments I make are at best banal, at worst, completely wrong-headed.

Here’s how the column opens:

The popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and beyond have seized the world imagination like no events since the collapse of the Iron Curtain. Regimes are teetering, dictators have fallen, and unexpected coalitions have managed to conjure street-level power seemingly out of thin air. Tunisians took credit for Egypt’s revolution; Egyptian demonstrators in turn claim they inspired people in Wisconsin and Bahrain.

Much remains uncertain, and even the most experienced observers have no idea who will hold power in the aftermath of these uprisings. But already we’ve learned more in a few short months than we gleaned from decades of careful study about the real power base of Moammar Khadafy and Hosni Mubarak, about the balance among armies and tribes, about the relative power of secular and Islamist activists. We’re seeing the true measure of oil money and the Muslim Brotherhood, of popular anger about corruption, and of the real interest in economic liberalization.

But perhaps the most surprising lessons emerging from all the unrest are even bigger ones — insights that extend well beyond the Middle East, and are forcing thinkers and policy makers to reconsider some basic assumptions that have long guided America’s foreign policy. How much impact can America really have on world events? How do our alliances function at crucial moments? Who really has the potential to initiate and control massive change in modern societies? The surprising answers suggested by the Arab revolts might create new options in the minds of American policy makers looking to advance not only US security and economic goals, but also the causes of human rights, transparency, and democratic governance.

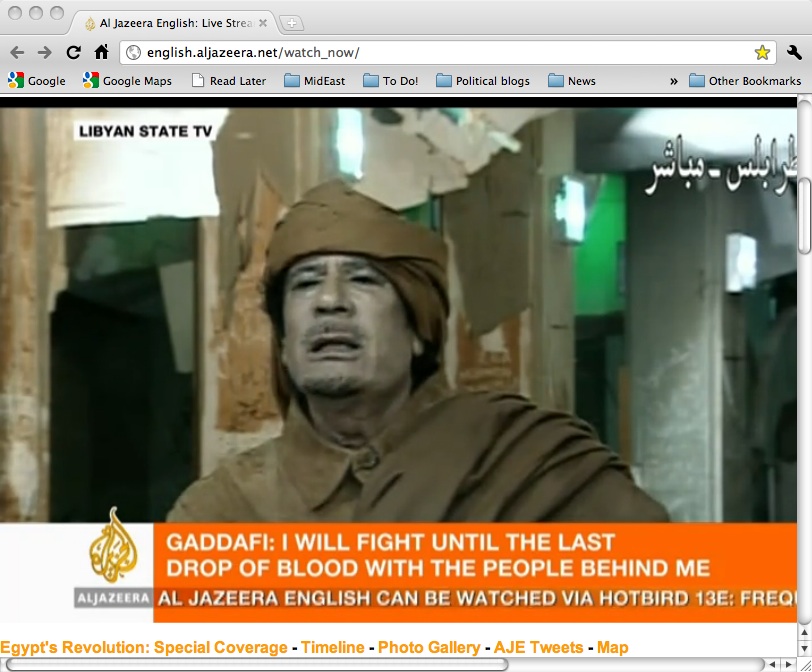

Madness & History

Watching Qaddafi on Al Jazeera right now – like watching Mubarak in Tahrir Square – was like peering down a sinkhole into a previous century. In this hallucination, men from another time, dressed in fashions long discarded, declaim in a wooden language that no longer has any purchase on our psyche. They don’t realize the disconnect. History has moved on. They are blaming provocateurs, satellite television, foreign plots, the Al Qaeda bogeyman. It’s madness! The delusion would be hilarious were it not so lethal.

“If you don’t follow Qaddafi who will you follow?” he says. “Someone with a beard?”

The Gamble for Egypt’s Future

The Atlantic has posted my essay about the next gamble for Egypt’s revolutionaries: Can they sustain pressure on the ancien regime?

The euphoria in Cairo already is already giving way to anxiety as Egyptians contemplate the terrifying task of dismantling Hosni Mubarak’s police state and building an accountable Arab democracy in the image of Tahrir Square.

The old order has been decapitated, but still exerts an undeniable gravitational pull over the entire polity. Thousands or possibly millions of policemen, informants, and clients of Mubarak’s state tremble at the prospect of transparency and, perhaps, retribution. If the protesters want to pursue reform, they will have to consider, and maybe even accommodate, those remnants of the old order.

On the morning before Mubarak resigned, I sat poolside with a group of retired generals at the Gezira Club, a members-only holdover of colonial times. A recently retired general from state security tried to interrogate me about the demonstrators; he was still convinced, against all evidence, that it was a Muslim Brotherhood uprising. The police, he was certain, would soon regain control of the nation. “How will the police regain public trust when they are so hated?” I asked. He couldn’t fathom what I was saying. “The majority of people love the police,” he shouted at me. “They will respect the police because they need the police.”

Old Egypt was on display elsewhere as well, in the patronizing and impatient tone in which the prime minister addressed the public in his first press conference after Mubarak’s downfall, in the capricious manner with which soldiers turned away some people at checkpoints while allowing others to pass, in the air of disgust with which some of Egypt’s millionaires, talking to me over cocktails at the Bodega Bar the day after Mubarak’s abrupt disappearance, dismissed the revolution as a failure that would usher in an anti-business government.

The revolutionaries, gambling as they have every step of the way, have gone for broke and demanded complete systemic reform: a new constitution written from scratch and an interim government purged of the Mubarak family and their Cardinal Richelieu, the spymaster and momentary Vice President Omar Suleiman. Perversely, though, the only way toward that goal was another, bigger, gamble: the revolutionaries have asked a military dictatorship to manage the transition in the hope that a committee of unelected generals who have spent a career defending Mubarak’s order will now willingly write themselves out of power.

The prospect may sound crazy, naïve, even delusional – but then again, three weeks ago so did the possibility of millions of Egyptians embracing civil disobedience and successfully castrating the Mubarak regime.

‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’

Egypt’s revolutionaries suspect the ecumenical and utopian nature of their wave will bless the next phase of their struggle. So many of the people I talked to on the streets today – before and after Mubarak skulked to his summer palace – already were busy imagining a future in their own indigenous vernacular. Mubarak’s cruelty drove them into a frenzy of rage, but once released from their state-induced torpor and timidity, they found themselves more interested in screaming about the things they wanted, rather than the things they wanted to get rid of.

Mubarak was a spark but also a footnote.

“He treated us all as if we were stupid,” said Leila Abdelbar, a staffer on parliament’s foreign affairs committee. “He underestimated us. He should have respected us.” She was angry, at a father who didn’t take his own children seriously. She also was angry at herself, for having acted for so long like she believed him.

“We have to thank our children for showing us the way,” she said, looking with adoration at her daughter Heba.

She and her friends are conservative Muslims, some of them wearing the full-face covering niqab. They’re not in the Muslim Brotherhood and they’re not interested in an Islamic state; they spoke with longing about a new constitution, a reconstituted judiciary, and a state that provided basic rights: rule of law, education, health and safety.

No one in the crowd used the American democracy vocabulary. They spoke with organic idioms, conjuring huriya, liberty, based on citizens who took their own rights, rather than received them as a leader’s prerogative. “We will take our rights,” many people repeated; they meant that they would demand a new compact, in which they would articulate their needs and if those needs went unmet, they would remake their state.

The specifics varied, and some people still drifted in vague hope for something better. Some talked of their right not to be arrested at will by unaccountable secret police. Some yearned for better schools and hospital care for the poor.

Protest leaders feted the moment but kept planning. “We’ll work until the last moment,” said Basem Kamel, one of the leaders of the Baradei civil reform campaign. Youth leaders were meeting at 1 a.m. to coordinate a clean withdrawal from the square and set negotiating terms for their discussions with the army (Kamel is 41 and balding, but youth is also a state of mind).

I have no doubt there will be reversals ahead, but Egypt has written a new chapter in modern history with utter disregard for all expectations for the contrary – their own as well as those of outsiders. There’s every reason to hope that the same millions of Egyptians who drove a tyrant to flee without firing a shot and without calling for the destruction of anything, and who discarded all their traditional corroded institutions to invent a unified popular front, might now manage the parlous task of writing a new constitution, convincing the military to abdicate to a truly civilian order, and crafting a polity dedicated to serving its own citizens’ conception of their right to justice, liberty and security.

“We did it,” Ziad Al-Alaimy said after lifting me off the ground in a bear hug. “Tomorrow belongs to us.”

It’s a long road ahead, surely, but as many people said: Egypt has learned the way to Tahrir Square. They won’t soon forget it, and let’s hope, neither will their new leaders.