9/11 Memoirs

The ninth anniversary of Sept. 11 passed in New York this weekend with a focus on the two fracases of the day: the “Ground Zero mosque” and the would-be Koran burners and their emulators.

The ninth anniversary of Sept. 11 passed in New York this weekend with a focus on the two fracases of the day: the “Ground Zero mosque” and the would-be Koran burners and their emulators.

For the decade between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the Twin Towers, many Americans turned away from the rest of the world, a regretful sort of superpower powernap. Talking about Sept. 11 is shorthand for talking about how America should exercise its power in the wider world, how to measure blowback, how to balance soft and hard power, how to curb extremism at its roots while also pruning its branches.

Anne and Manny Fernandez wrote a piece yesterday that catalogues what 9/11 looks like today, rather than trying in overwrought prose to figure out what it means. They focus on “an unmistakable sense that a once-unifying day was now replete with division” – although one could argue that from the first decisions that followed the Sept. 11 attacks American political life grew more divided than ever.

In a similar vein, I reviewed Scott Malcomson’s memoir in the Times’ Sunday Book Review section. Reading his recollection of 9/11 and the years that followed forced me for the first time in ages to recall their intensity and the sense of a bottom falling out.

The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, found me on my stoop in Boston’s South End, waiting for a ride to work. One minute I was enjoying the sunshine, worrying about the logistics of moving house. Then the first plane struck the north tower of the World Trade Center and my entire frame of reference lurched. What I don’t quite remember is how that painful, personal moment connected to America’s national experience in the aftermath of the attacks — and to what many saw as the erosion of civil liberties, unnecessary wars and the willingness to scorn allies and international institutions.

It is this link that concerns Scott L. Malcomson in “Generation’s End: A Personal Memoir of American Power After 9/11.” How, Malcomson inquires, did the world’s sole superpower surrender its better judgment and squander so much good will? Read the rest.

Normalcy, perhaps, is a feeling that only prevails in historical retrospect.

Egypt’s military and its next president

In Sunday’s New York Times I wrote about the Egyptian military’s central role in Egyptian society and what position it might take on the selection of President Hosni Mubarak’s successor. So much is opaque in Egypt’s power structure, and nobody outside Mubarak’s inner sanctum has a clear picture of how anything works, precisely. The retired military officers, opposition leaders, defense consultants, officials, and analysts that I interviewed are either expressing the views of an interested party in the case of the officials and politicians, or are cobbling together theories from a sort of reading of the tea leaves.

In Sunday’s New York Times I wrote about the Egyptian military’s central role in Egyptian society and what position it might take on the selection of President Hosni Mubarak’s successor. So much is opaque in Egypt’s power structure, and nobody outside Mubarak’s inner sanctum has a clear picture of how anything works, precisely. The retired military officers, opposition leaders, defense consultants, officials, and analysts that I interviewed are either expressing the views of an interested party in the case of the officials and politicians, or are cobbling together theories from a sort of reading of the tea leaves.

Even those who believe the military could play an important role have few ideas of how, in practice, the military would exercise that role. Possibilities include:

- A military coup, which most people said was unlikely.

- An expanded role in direct rule, for example by moving to completely shut down the Muslim Brotherhood.

- An internal negotiation with potential successors that protects the military’s continued privileged status

- A tense internal negotiation in which the military does not obtain the assurances it wants, and then seeks to undermine the next president.

- A weak successor who faces a public opinion crisis similar to the uproar in Egypt during the 2008-2009 Gaza war, when Mubarak kept the border closed and essentially sided with Israel over Hamas. In that case, one official source speculated, the military might organize a direct or indirect coup if it fears an ineffective president will be unable to keep domestic order in a time of crisis.

Issandr El Amrani, author of the excellent Arabist blog, gave me a very helpful interview for the story and elaborated further on his blog about the succession prospects. It’s worth reading the whole post, but here’s his thesis:

This situation, in a sense, is ideal for the military, confirming its central role and placing senior military officers — since we are probably talking about that rather than the army as a corporate entity — of winning either way: they will be wooed by Gamal (or any other successor) to support him and, if they decide not to, would easily garner popular support for their own candidate. Should they decide to support Gamal Mubarak, they need do nothing but sit back and allow the process concocted for his “legitimate” election to take place. If they decide against it, it will be most likely a decision taken behind the scenes rather than publicly, with the selection of the candidate taking place in collusion with elements of the ruling party rather than, as some have said, by tanks descending into the streets. A soft coup, if you will, if only because the regime as a whole in Egypt has an interest in preserving the myth of constitutional legitimacy — they would bend the rules, rather than break them altogether.

Stephan Roll, a Berlin-based researcher, also wrote about the military and succession at the Carnegie Endowment’s Arab Reform Bulletin (another version of the essay ran in Al Masry Al Youm’s English edition). He sees the military as a fulcrum point between the ruling party’s old guard and new guard.

For the first time in Egypt’s modern history, the business elite are playing a role in the succession question, but it is still not clear whether that role will be decisive. … So far, the military leadership has kept out of the power struggle between old and new guards inside the party and the government. In general, this neutrality seems to serve the interests of the old guard, as a positive signal by important military officers regarding the new guard and Gamal Mubarak would certainly give them a boost.

As with most of the questions about Mubarak’s successor, the most interesting decisions are likely to be made outside of the public eye, and many of them – like the military’s struggle to maintain its position, or like the ruling party’s internal split between two factions of very rich officials – might take several years to play out. The military has received nearly $40 billion from the United States, which prizes the Egyptian military’s stability and Washington-allied positions. The U.S. also appreciates the Egyptian military’s agreement to stay out of regional affairs, concentrating on defending Egypt’s regime and borders.

The military has much to lose in the transition, these officers and analysts say. Over the years, one-man rule eviscerated Egypt’s civilian institutions, creating a vacuum at the highest levels of government that the military willingly filled. “There aren’t any civilian institutions to fall back on,” said Michael Hanna, a fellow at the Century Foundation who has written about the Egyptian military. “It’s an open question how much power the military has, and they might not even know themselves.”

Bahrain’s unfolding crackdown

Since the middle of Ramadan, when I wrote about Bahrain’s sweep of Shia activists, the government has announced charges against 23 alleged coup plotters, saying they were planning to overthrow the government with funding from abroad, mainly Iran.

Since the middle of Ramadan, when I wrote about Bahrain’s sweep of Shia activists, the government has announced charges against 23 alleged coup plotters, saying they were planning to overthrow the government with funding from abroad, mainly Iran.

Bahraini human rights activists continue to protest the government’s detention of hundreds of Shia politicians and activists; on Sept. 11 they began a “sit-in,” pictured here, demanding an end to torture and the release of all those detainees not charged with a crime.

King Khalifa gave an angry speech, saying the years of tolerance and pardons were over, while the government belatedly started making a case to public opinion beyond the Gulf, addressing the allegations of torture and illegal detention while also articulating claims that the Shia political opposition figures it arrested pose an actual threat to the state.

Bahrain’s Ambassador to the U.S., Houda Ezra Ebrahim Nonoo, wrote in her letter to the Times:

Against the backdrop of continuing incidences of violence and public disorder, arrests were made because significant evidence was discovered of a network planning and instigating attacks on public property and inciting violence. … Our commitment to further reform within an open, tolerant Middle East society remains undiminished.

Solid evidence could help that case, but so far the Bahrain case highlights some really interesting regional questions.

- Can the ruling families in the heterogenous Gulf countries find a way to extend minority rights while maintaining stability?

- Are the Shia minorities in Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia seriously interested in taking power, like the Shia in Iraq, or will they be satisfied with a more fair political system?

- Is Iran actively stirring up the Shia in the Gulf countries as a threat to ruling families, or are we seeing nothing more than flow of alms money from religious Shia through their references – usually based in Iran and Iraq – back to the faithful in the Gulf?

- How much rule of law is possible in states were absolute authority is concentrated in the hands of a single, hereditary ruling family?

- What is the Khalifa family trying to accomplish long-term? And what prompted the timing of this wave of arrests: Real information about a prospective coup? Concerns that Shia parties would win a majority in the October parliamentary elections? Real worry that simmering unrest would hurt Bahrain’s ability to win and retain foreign companies?

The Bahraini press has begun to publish some of the government’s answers to these questions. There have been some newspaper columns in the Gulf that express the ruling families’ fear of Iran-backed Shia uprisings, an anxiety that has percolated throughout the peninsula in various forms for centuries.

Steven Sotloff wrote an excellent piece on The Middle East Channel about Bahrain’s Shia crackdown, in which he details a lot of the background in what he describes as conflict not between Shia and Sunni but between the Shia majority and the ruling Khalifa family. Sotloff gives us a lot of useful detail about the government’s housing policy, which favors newly naturalized Sunni immigrants recruited for the security forces over long-time Shia citizens, and other Shia grievances about employment and political rights. His measured tone helps referee a lot of the heated claims about Iranian funding, dual loyalty and sedition.

Brotherhood boycott?

Parliamentary elections are coming up this fall in Egypt, probably in October or November. But the opposition and ruling National Democratic Party alike have their eyes on presidential succession, assuming that President Hosni Mubarak, who is ill and has ruled for 29 years, probably won’t run again in 2011. In that light, the parliamentary elections have become part of the broader political jockeying.

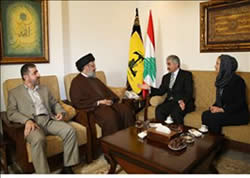

The Muslim Brotherhood commands by far and away the strongest street support among the opposition factions, but it’s a banned society whose parliamentary representatives are technically independents. Meanwhile, the secular opposition parties want to boycott the parliamentary elections to protest the ruling party’s heavy-handed manipulation of the voting process (since the last election, for instance, the government has cancelled the judiciary’s right to oversee polling stations). That’s the Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide Mohammed Badie in the picture, getting yelled at by secular opposition leaders during an iftar.

The Brotherhood and the secular National Association for Change are circulating a petition calling on the government to amend the constitution and reform the voting process to allow free and fair elections. It’s a rare instance of the Islamist and secular opposition working together, but even in this arena they’re competing to show who’s stronger. The Brotherhood has collected nearly 700,000 signatures; the National Association for Change only 100,000. You can follow the dueling signature drives on the Brotherhood petition page and the NAC petition page.

You can also read more about the Brotherhood’s internal debate between seeking power and challenging it in my story today in The New York Times.

CAIRO — One by one, the guests at the Muslim Brotherhood’s annual Ramadan iftar banquet strode to the rostrum. A who’s who ofEgypt’s opposition began hectoring the Islamist group. The Brotherhood, they said, by far the most muscular and influential of Egypt’s dissident organizations, should withdraw from the coming parliamentary election that would most certainly be rigged by the authoritarian government.

“Why won’t you take the initiative?” shouted Karima El-Hefnawi, a secular activist and leader of the popular Kifaya protest movement. “Why won’t the Muslim Brotherhood boycott this farce?” The supreme guide of the Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie, sat uncomfortably a few feet to her right.

At the close of the evening, Mr. Badie was noncommittal. The Brotherhood, he said, in time would make up its mind: “Haste makes waste.”

The Muslim Brotherhood is engaged in a delicate dance. Despite all efforts to marginalize the Islamist organization by the United States and its close ally, the Egyptian government, it remains the most credible opposition group. Some of its members want the Brotherhood to fight the government head on, but the Islamist leadership has other goals: freedom to proselytize and organize in neighborhoods, and in the long term, a lifting of the official government ban on its activities.

With an end in sight to President Hosni Mubarak’s 29-year reign, the Brotherhood appears to be signaling its willingness to cut a deal with Mr. Mubarak’s potential successors by not overtly challenging the ruling party’s monopoly on power.

Iraq’s Narrative

What is the long arc of America’s involvement in Iraq?

For two very different approaches to this question, take a look at the a Defense Department official’s description of the blueprint for Iraq and Anthony Shadid’s wrenching story of one family’s encounter with Operation Iraqi Freedom. Each in their way is trying to make sense of the seven-year war, giving us a story line to make sense of what’s happened, where Iraq is going, and what it might mean.

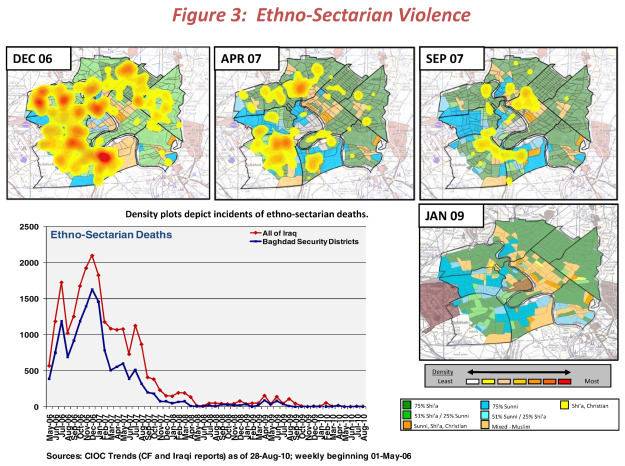

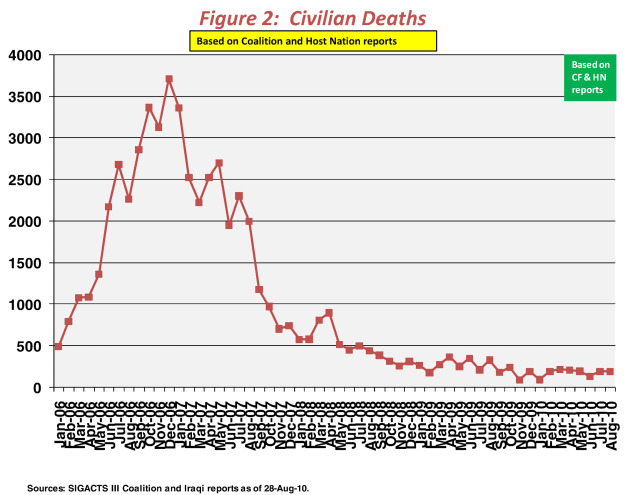

On ForeignPolicy.com’s Middle East Channel, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for the Middle East Colin H. Kahl outlines America’s goals in Iraq for 2011 and beyond. Most interesting are some of the details, like the mention that America’s civilian presence in the long-term will be concentrated in the Kurdish north, and the rhetorical shift from war and occupation to “strategic partnership” and a “train-and-equip” military mission. In Defense Department fashion, the most compelling illustration of the narrative arc comes in these Power Point slides, which show death tolls.

For a sense of what those deaths look and feel like, we can turn to Anthony, who deploys his formidable gifts to tell us the human narrative. He delivers the kind of sweeping, gripping tale that we’ve come to expect from him. In this case, he accompanies a family that is searching for one of its dead five years after his murder and disappearance.

For a sense of what those deaths look and feel like, we can turn to Anthony, who deploys his formidable gifts to tell us the human narrative. He delivers the kind of sweeping, gripping tale that we’ve come to expect from him. In this case, he accompanies a family that is searching for one of its dead five years after his murder and disappearance.

The odyssey contains so much of what defines life in Iraq: fear, death, bureaucracy, sectarian resentment and underlying it all, a deep strain of bewilderment. In one scene, the Sunni family goes to a police station in a Shia area for a document they need in order to obtain a death certificate.

The family needed a letter from the police station, the first step in claiming Muhammad’s death certificate and finding out where he was buried. With Hamid beside her, the mother pleaded to let them inside. For five years they had looked for him, she said.

The policeman glared at her suspiciously. “If you’re lying, I’ll put you all in jail right now,” he shouted.

“My son is dead, and this is what you say to us?” the mother answered.

The policeman turned his head in disgust.

“Dog,” he muttered under his breath.

Slogans litter Baghdad. They are scrawled on the blast walls that partition this city of concrete. They proclaim unity from billboards over traffic snarled at impotent checkpoints. The more they are uttered, it seems, the less resonant they become.

“Respect and be respected,” read the one the family passed, entering the police station.

Greekonomics

During our vacation in July, I reported a piece for The Boston Globe Ideas section about the economic crisis in Greece, which was just published today. Two questions intrigued me. How much would the collapse of the economy degrade actual quality of life? And had the Greeks proved that market orthodoxy was partly based on a mirage by calling its bluff and surviving?

During our vacation in July, I reported a piece for The Boston Globe Ideas section about the economic crisis in Greece, which was just published today. Two questions intrigued me. How much would the collapse of the economy degrade actual quality of life? And had the Greeks proved that market orthodoxy was partly based on a mirage by calling its bluff and surviving?

The answer, I found, was that average working Greeks were suffering substantial losses, and were bracing for far more in the fall — for starters 5 to 10 percent cuts in real wages and real pensions for many people, in addition to increased taxes. That’s not taking into account rising unemployment, social tension, and macroeconomic changes.

For Greece, the real test comes in the next few months, when the government tries to move ahead with the austerity plan it promised Europe in exchange for the bailout, and Greek unions take to the streets.

What happens next will resonate far beyond this small country’s borders. Greece is about to learn whether a modern state can withdraw entitlements that people have come to take for granted but which the government no longer can afford. For fiscal hawks, this is a harbinger of what could happen to the American economy when, say, the social security system finally goes bankrupt, or when the government no longer has enough money to fund Medicare. For Greeks, it’s something else as well — a kind of identity crisis for a way of life defined almost as a rebuke to contemporary liberal market economics.

Americans, the saying goes, live to work; Greeks work to live. As a credo, it reflects a Greek belief that a worker on any rung of the class ladder deserves security and pleasure in exchange for hard work. It’s not outsized salaries or short workdays that define the Greek model. First and foremost it’s job security: Until recently Greeks struggled to find jobs, but once employed they never feared losing them. A close second is the principle of egalitarian access to the pleasures of life: going out to eat or listen to music on the weekends, and taking your family on Easter and summer vacations.

From the outside, the Greek sense of entitlement is often misunderstood as a desire for some kind of lazy lifestyle. In actuality, though, most of the government and union workers raising hell in the streets work hours as long as any American blue collar or office worker; many of them, in fact, work two jobs — at a bank or ministry in the morning, driving a taxi in the evening. What Greeks have treasured for decades and are now contemplating losing is the kind of job security that most Americans surrendered in the 1970s. All those wasteful government jobs underwrote a vast reservoir of public confidence, and in large measure blessed Greece with a joie de vivre. Small entrepreneurs don’t feel as stressed when the government countersigns their loans and when they know, if the business fails, they still have a stable job at the state water and sewer authority.

New York, Viewed from the Rest of the World

I’ve spent much of the last week covering the Park51 story from the Arab world. The entire affair has attracted far less attention in the Islamic world than one might expect. We put together a story that canvassed global reaction in today’s Times.

I’ve spent much of the last week covering the Park51 story from the Arab world. The entire affair has attracted far less attention in the Islamic world than one might expect. We put together a story that canvassed global reaction in today’s Times.

If the project’s organizers move the site, or cancel it altogether, I’d expect stronger opinions than we’ve seen so far. Same if there’s a major shift in public opinion, or a spate of violent attacks, or nastier rhetoric than we’ve seen so far.

For more than two decades, Abdelhamid Shaari has been lobbying a succession of governments in Milan for permission to build a mosque for his congregants — any mosque at all, in any location.

For now, he leads Friday Prayer in a stadium normally used for rock concerts. When sites were proposed for mosques in Padua and Bologna, Italy, a few years ago, opponents from the anti-immigrant Northern League paraded pigs around them. The projects were canceled.

In that light, the furor over the precise location of Park51, the proposed Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan, looks to Mr. Shaari like something to aspire to. “At least in America,” Mr. Shaari said, “there’s a debate.”

Across the world, the bruising struggle over an Islamic center near ground zero has elicited some unexpected reactions.

For many in Europe, where much more bitter struggles have taken place over bans on facial veils in France and minarets in Switzerland, America’s fight over Park51 seems small fry, essentially a zoning spat in a culture war.

But others, especially in countries with nothing similar to the constitutional separation of church and state, find it puzzling that there is any controversy at all. In most Muslim nations, the state not only determines where mosques are built, but what the clerics inside can say.

The one constant expressed, regardless of geography, is that even though many in the United States have framed the future of the community center as a pivotal referendum on the core issues of religion, tolerance and free speech, those outside its borders see the debate as a confirmation of their pre-existing feelings about the country, whether good or bad.

Suburbs a Pharaoh Would Conceive

A few million people have moved to these new cities springing up in the desert outside of Cairo – and they’re nowhere near done. The scale of these places boggles the imagination.

A few million people have moved to these new cities springing up in the desert outside of Cairo – and they’re nowhere near done. The scale of these places boggles the imagination.

Driving around these new developments, we saw billboards for dozens more in the planning stages. I had in mind Max Rodenbeck’s book Cairo: The City Victorious, especially when some people told me these new desert cities would kill Cairo. Max notes that such complaints were rife a millennium ago, and the city somehow survived. A few decades from now, perhaps there won’t be any open desert to speak of between today’s Cairo and its young sibling settlements, 6 October City and New Cairo.

The highway west out of Cairo used to promise relief from the city’s chaos. Past the great pyramids of Giza and a final spasm of traffic, the open desert beckoned, 100 barren miles to the northwest to reach the Mediterranean.

That, at least, was the case until recently. Now, the microbus drivers and commuters driving from Cairo cross 20 miles of nothingness to encounter a new city suddenly springing from the sand. A distressingly familiar jam of cars and a cluster of soaring high-rises herald the metropolis that is designed to relieve pressure on the historic center of Cairo, which city planners have deemed overtaxed beyond repair.

Welcome to the new Cairo, not entirely different from the old one.

Cairo has become so crowded, congested and polluted that the Egyptian government has undertaken a construction project that might have given the Pharaohs pause: building two megacities outside Cairo from scratch. By 2020, planners expect the new satellite cities to house at least a quarter of Cairo’s 20 million residents and many of the government agencies that now have headquarters in the city.

Only a country with a seemingly endless supply of open desert land — and an authoritarian government free to ignore public opinion — could contemplate such a gargantuan undertaking. The government already has moved a few thousand of the city’s poorest residents against their will from illegal slums in central Cairo to housing projects on the periphery.

The “Ground Zero” Imam

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, leader of the Park51 project (you know, the Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan), kept quiet about the controversy back home during his visit to Bahrain this week. He was on a US State Department trip promoting interfaith dialogue, tolerance, and his long-running project to inject his philosophy of adaptable American Islam into the worldwide Islamic debate. Initially, the State Department tried to shield the imam from publicity, but eventually relented – slightly – by making public one event in each of the three countries Imam Feisal is visiting.

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, leader of the Park51 project (you know, the Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan), kept quiet about the controversy back home during his visit to Bahrain this week. He was on a US State Department trip promoting interfaith dialogue, tolerance, and his long-running project to inject his philosophy of adaptable American Islam into the worldwide Islamic debate. Initially, the State Department tried to shield the imam from publicity, but eventually relented – slightly – by making public one event in each of the three countries Imam Feisal is visiting.

In Bahrain, I managed to secure my own invite to the majlis of Sheikh Salah al-Jowder. He’s an oddity, a moderate salafist who sits on an interfaith dialogue committee in Manama (it’s interesting that such a thing even exists). There, Imam Feisal talked a bit about the center, because his hosts had a lot of questions.

The latecomers to Sheik Salah al-Jowder’s majlis, or weekly assembly, wished peace upon their cousins and shook all the men’s hands before sitting down on the deep striped sofas that lined the oblong reception hall.

Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, leader of the planned Park51 Islamic community center in Lower Manhattan, was sipping Arabic coffee about an hour before midnight Sunday in Muharraq, a crowded neighborhood near the international airport.

On the first stop of his good-will tour, sponsored by the State Department, Mr. Abdul Rauf talked expansively about religious law, the lessons of Islamic history and his mission to build bridges between the West and the Islamic world — any topic, it seemed, but the controversy that lately has made him famous.

About 20 Bahraini men, in flowing white robes and headdresses held in place with braided leather bands, fiddled with their BlackBerrys, drank coffee and fingered beads.

After Mr. Abdul Rauf had spoken, and exchanged pleasantries with his hosts, one of the Jowder cousins raised his voice.

“I know you have the support of President Obama,” he said, almost shouting to be heard over the air-conditioners. “But why don’t we just change the place, to show that Islam is not there to threaten everybody, that Islam is a religion of peace?”

Imam Feisal is in Qatar now, and will visit the United Arab Emirates before returning to the U.S. in early September. He said he will talk to the American media then. For now, he insists, he wants to focus on the Cordoba Initiative’s outreach project.

A lot of his most controversial ideas – at least in the Islamic world – have to do with his belief that Islam takes a different shape in every host culture. American Islam, Imam Feisal argues to his audiences in the Islamic world, has just as much religious legitimacy as Egyptian Islam, or Persian Gulf Islam, or Malaysian Islam, and so on. He makes his argument quietly, but it’s a position that runs squarely counter to the trends in the Arab world toward a more orthodox view of Islam. Imam Feisal believes that Muslims in Egypt can learn from the way American Muslims interpret their faith, and not just vice versa.

For a sense of those ideas and their origin, you can read Anne Barnard’s fabulous profile of Imam Feisal (on which I collaborated from Cairo). She also parses some of the claims about him circulating in the blogosphere.

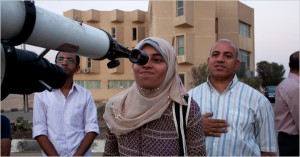

The Ramadan Moon, Lost in Haze

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

HELWAN, Egypt — The observatory director, Salah M. Mahmoud, squinted at the smog gathering over the distant Nile.

“It looks like trouble,” he said.

His deputy, Ahmed Fathy, concurred with a sigh, “I’m afraid we’re not going to see anything tonight.”

The two Egyptian physicists on Tuesday night had a delicate mission: They were charged with providing the scientific imprimatur to the start of the holiest time for Muslims worldwide, the lunar month of Ramadan. Egypt plays a major role in this ritual because it is the seat of Al Azhar, the world’s most prominent Sunni Muslim institution.

According to the Koran, Ramadan, a month of fasting and prayer, begins on the first night that the crescent moon is visible to the naked eye. For centuries, clerics and laymen jostled to spot the Ramadan moon first and often differed. An area with cloudy skies or a different longitude and latitude might declare Ramadan a day or even two later than the rest of the Islamic world.

Modern astronomy long ago took the mystery out of the lunar calendar, whose year lasts some 11 to 12 days less than the Gregorian year used by most non-Islamic countries.

Mr. Mahmoud, the president of Egypt’s National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, publishes a hefty book of tables that lists the precise time and location that the Ramadan moon will appear in various cities throughout the Islamic world.

But science, it seems, can go only so far.

“We know it’s there, but Shariah requires us to see it with our eyes,” Mr. Mahmoud explained. The grand mufti, Egypt’s highest religious authority, awaits a report from Mr. Mahmoud’s team and from a secondary group of spotters organized by the Egyptian National Survey Authority.

On Assignment in Cairo

Last week I got to Egypt, where I’ll be based for the rest of the month, covering the Arab world for The New York Times. I’ll cross-post my stories here. All ideas and suggestions are welcome.

Britain Reconsidering Hezbollah Channel?

In a recent interview with Asharq Alawsat, the United Kingdom’s new Conservative Minister for the Middle East Alistair Burt said that Britain was reconsidering its policy of limited relations with Hezbollah. In 2008, after a three-year hiatus, the British Foreign Office quietly resumed its policy of allowing diplomats to talk to Hezbollah’s “political wing,” making a distinction between the organization’s political and military sides that Hezbollah itself does not.

In a recent interview with Asharq Alawsat, the United Kingdom’s new Conservative Minister for the Middle East Alistair Burt said that Britain was reconsidering its policy of limited relations with Hezbollah. In 2008, after a three-year hiatus, the British Foreign Office quietly resumed its policy of allowing diplomats to talk to Hezbollah’s “political wing,” making a distinction between the organization’s political and military sides that Hezbollah itself does not.

Burt didn’t say the U.K. would cut off the limited dialogue between its diplomats and Hezbollah’s elected members of parliament, but that the British government would review all future contacts:

It is still too early to say if we are going to adopt the approach of the previous government with regards to distinguishing between the political and military wings of Hezbollah. … There may be occasions where limited communication would be in everybody’s interests and the interests of the peace process in general. However we will place such communication under constant review, and on a case by case basis.

The British Labor government kept more open channels with Middle Eastern militants than the United States has, at times drawing rebukes from Washington. It will be interesting to see whether the new Conservative government continues the same approach.

Ayatollah Fadlallah’s Legacy II (Updated)

David Kenner at foreignpolicy.com writes incisively about Fadlallah’s legacy as a religious leader who inspired Hezbollah and the Dawa Party but charted an independent course. As Kenner chronicles, the United States government misunderstood Fadlallah’s role, for years mistakenly considering him an operational leader of Hezbollah and trying to assassinate him in 1985.

There was an element of truth to the U.S. stance: Fadlallah was certainly no liberal, nor an ally to be recruited to advance U.S. security goals. However, even a quarter-century after that misguided assassination attempt, U.S. officials failed to appreciate the areas where their interests and Fadlallah’s overlapped, both in isolating Iran and reducing the appeal of fundamentalism within Lebanon. The United States always preferred blunt instruments and simple epithets — crude tools indeed for a complex man.

Unlike Hezbollah leaders, Fadlallah liked to meet with and debate those with whom he disagreed. A remarkable testament to this side of Fadlallah comes in this remembrance posted by the British Ambassador to Lebanon Frances Guy on her blog (where she regularly writes with surprising candor about things that other diplomats will hesitate to discuss as openly at background briefings).

When you visited him you could be sure of a real debate, a respectful argument and you knew you would leave his presence feeling a better person. That for me is the real effect of a true man of religion; leaving an impact on everyone he meets, no matter what their faith. … The world needs more men like him willing to reach out across faiths, acknowledging the reality of the modern world and daring to confront old constraints. May he rest in peace.

UPDATE

Fallout continues for public figures who praised Fadlallah after his death. First, CNN fired long-time Middle East editor Octavia Nasr after she posted a comment on Twitter expressing her sadness at the passing of a “Hezbollah giant” whom she “greatly respected.” (No matter that he wasn’t actually a Hezbollah figure, although he provided the religious justification for many of its tactics, include suicide bombings.) Now, the British Foreign Office has taken down Ambassador Guy’s blog post, “after mature consideration,” a spokesman told the Guardian newspaper.

Here’s the full text, of the post, as preserved by the Guardian.

One of the privileges of being a diplomat is the people you meet; great and small, passionate and furious. People in Lebanon like to ask me which politician I admire most. It is an unfair question, obviously, and many are seeking to make a political response of their own. I usually avoid answering by referring to those I enjoy meeting the most and those that impress me the most. Until yesterday my preferred answer was to refer to Sheikh Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah, head of the Shia clergy in Lebanon and much admired leader of many Shia muslims throughout the world. When you visited him you could be sure of a real debate, a respectful argument and you knew you would leave his presence feeling a better person. That for me is the real effect of a true man of religion; leaving an impact on everyone he meets, no matter what their faith. Sheikh Fadlallah passed away yesterday. Lebanon is a lesser place the day after, but his absence will be felt well beyond Lebanon’s shores. I remember well when I was nominated ambassador to Beirut, a Muslim acquaintance sought me out to tell me how lucky I was because I would get a chance to meet Sheikh Fadlallah. Truly he was right. If I was sad to hear the news I know other peoples’ lives will be truly blighted. The world needs more men like him willing to reach out across faiths, acknowledging the reality of the modern world and daring to confront old constraints. May he rest in peace.

The Decisive Ones

At Length Magazine has just published a short memoir I wrote of the early days of the Iraq invasion. You can find it under prose on the homepage, or you can click here to link directly to the piece. Here’s how it opens:

“Fuck you fuck you fuck you. Fucking American army piece of shit,” Sa’ad al-Azawi chanted behind the wheel of his BMW. He couldn’t recognize his own city, he couldn’t navigate it. He just wanted to hop across the July 14 Bridge to the manicured center of the city’s power, Baghdad’s palm-lined answer to the Washington Mall, soon to be home to the occupation headquarters. A tank blocked an on-ramp. We had to circle west along the Tigris River and then back east again to get to the Rashid Hotel.

Baghdad’s map had become malleable, old routes across town melting away like mercury and reforming in odd places. Americans had closed some roads and bridges with checkpoints. They had cut others with bombs. Buildings were missing in action. Pits of rubble had replaced homes, like an entire block that included a Saddam safe house behind a Mansour restaurant. A bunker buster had buried a three-story house in a pit 20 feet deep.

Along the approach to Baghdad, every hundred yards or less, a killed car askew beside the road — either a rotting driver, shot to death, or a charred car frame from a direct hit on the car by some kind of bomb. (Rocket? RPG? Mortar? So early in the war, I certainly couldn’t tell.) Bullet casings at every intersection, detours around each part of the highway bombed into a moonscape. A bloated dead donkey blocked the bridge across the Tigris in downtown Baghdad. You could date the bodies in the cars and sometimes on the sidewalks by their shape and smell. Within days of death the skin turned black. As they decomposed they bloated to twice their normal size. And they smelled stronger than anything I’ve smelled before, like that rush up the back of your nose from your stomach just before you vomit, and then blooming into something worse.

Ayatollah Fadlallah’s Legacy

Lebanon’s Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah died on Sunday, snuffing out one of the most important voices for reform and restraint inside the milieu of Shia Islamism. As I wrote in Fadlallah’s obituary in The New York Times, the cleric had made his name as an advocate for the Shia awakening in the 1960s and 1970s, and then as a justifier of suicide bombings by Islamists.

Lebanon’s Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah died on Sunday, snuffing out one of the most important voices for reform and restraint inside the milieu of Shia Islamism. As I wrote in Fadlallah’s obituary in The New York Times, the cleric had made his name as an advocate for the Shia awakening in the 1960s and 1970s, and then as a justifier of suicide bombings by Islamists.

But he also won droves of supporters all across the Islamic world, including the non-Arab nations, because of his work on family law. He found that women should have an easier time winning divorces under Islamic law, and that they have the right to defend themselves from domestic violence. He directed vast sums of money to hospitals and charity groups, even setting up for-profit businesses like hotels and gas stations in under-served Shia areas and then funneling the proceeds to his social services network. Most of the Shia women I know, even those who sympathize with Hezbollah, considered Fadlallah their religious reference.

In January 2009, I interviewed him at his official headquarters around the corner from the mosque where he preached. He railed against the infighting in the Islamic world between Shia and Sunni Muslims, and between Muslims and Christians. Eventually, he said, America and Iran would arrive at a rapprochement, and so too would Israel and its neighbors (this last statement surprised me the most).

To a Westerner, it might be hard to distinguish among the different marjas, or “sources of emulation,” that devout Shia Muslims follow. They all believe that religious jurists have the right to issue fatwas on everything from marital relations to geopolitics. Beyond this common point, however, leaders like Fadlallah – and to a lesser extent, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani in Najaf – have provided a very different model than some of their counterparts in Qom, who advocate the Iranian model of wilayat al faqih, or direct rule by the jurisprudent (that is, the ayatollahs govern directly.)

Fadlallah believed the authority of the clerics depended on their authority among the people (and not solely from their divine link to God). He also believed that Islamic resistance had to retain its “humanism,” and therefore he condemned acts and movements that considered terrorist – like the Sept. 11 attacks, and the ongoing efforts of Al Qaeda. “We are not at war with the American nation,” he told me.

There aren’t many religious leaders whose views carry such weight and yet are willing to criticize their own followers and the movements that they inspire. Now there’s one fewer.

Terrorist Talkers

It’s a banner day for the topic I’ve been researching all spring : What tools beyond direct force can Western government use to engage, modulate or otherwise shape the behavior of listed terrorist groups? I’ve been studying in particular the use of intelligence community contacts, diplomacy, creative government engagement through aid and trade, and Track Two diplomacy (which we might as well call secret negotiations, since almost all of the important initiatives take place with the full knowledge of the governments involved).

It’s a banner day for the topic I’ve been researching all spring : What tools beyond direct force can Western government use to engage, modulate or otherwise shape the behavior of listed terrorist groups? I’ve been studying in particular the use of intelligence community contacts, diplomacy, creative government engagement through aid and trade, and Track Two diplomacy (which we might as well call secret negotiations, since almost all of the important initiatives take place with the full knowledge of the governments involved).

In the wake of last week’s Supreme Court ruling on the material support statute, which holds that political advice amounts to assistance for terrorist groups, several advocates of off-line diplomacy have reiterated their arguments for engagement.

First comes Mark Perry, author of the book Talking to Terrorists published earlier this year. He argues that the United States, Europe and Israel gain nothing by boycotting groups like Hamas and Hezbollah, because those groups are here to stay and represent large and growing constituencies. Perry broke the story in March that General David Petraeus had told the White House that America’s pro-Israel stance was harming core national interests in the Islamic world. Now, he’s gotten his hands on another CentCom document in which he reports that some military propose that Hamas should be integrated into the Palestinian Authority security forces and Hezbollah into the Lebanese Army. Both groups, the authors of the military memo argue, should receive American military training, even though they’re defined as foreign terrorist organizations by the U.S. government. (The officers were on a so-called “Red Team” tasked with challenging assumptions and considering alternative ideas.)

The CENTCOM team directly repudiates Israel’s publicly stated view — that the two movements [Hamas and Hezbollah] are incapable of change and must be confronted with force. The report says that “failing to recognize their separate grievances and objectives will result in continued failure in moderating their behavior.”

Meanwhile, on the op-ed page of The New York Times today, the academics Scott Atran and Robert Axelrod write that informal diplomacy has played a crucial role in convincing terrorist groups to renounce violence and enter politics. They cite historical Track Two negotiations begun by private citizens in the transformation of the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Real Irish Republican Army. They also cite their own back-channel conversations with Palestinian militant groups, including Hamas and Islamic Jihad, which they said have yielded important insights.

Private citizens can talk to leaders who are off limits to policy-makers, and can report their findings; in this instance, Atran and Axelrod write, Islamic Jihad reveals itself as recalcitrant and committed to fighting Israel, whereas a Hamas leader suggested he would consider not just a truce (hudna) but peace (salaam). Atran and Axelrod caution that off-line private diplomacy requires expertise and discretion: “Accuracy requires both skill in listening and exploring, some degree of cultural understanding and, wherever possible, the intellectual distance that scientific data and research afford.”

It’s an uncomfortable truth, but direct interaction with terrorist groups is sometimes indispensable. And even if it turns out that negotiation gets us nowhere with a particular group, talking and listening can help us to better understand why the group wants to fight us, so that we may better fight it. Congress should clarify its counterterrorism laws with an understanding that hindering all informed interaction with terrorist groups will harm both our national security and the prospects for peace in the world’s seemingly intractable conflicts.

Advocates of such talks usually take care not to oversell their potential, given that talking to terrorists rarely yields quick results and frequently yields none at all, except for political fallout when secret talks are leaked. All three of these authors have written publicly about their private conversations with leaders of listed terrorist groups. Their conversations were conceived as part of a concerted effort to convince the groups in question to renounce terrorism and violence and pursue their grievances in a legitimate political forum.

It’s unclear whether the Supreme Court ruling would affect these freelance diplomats, who tend to report their foreign terrorist contacts to the government and conduct their diplomatic experiments more or less with their government’s blessing. But for now American law – and grand strategy – have perhaps intentionally left in a fuzzily defined gray area the question of what kind of engagement best complements national counter-terrorism efforts.

Can You Tell a Terrorist to Abandon Violence?

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, it appears that Americans aren’t allowed to interact with listed terrorist groups, even to provide them the kind of assistance that on its face would appear to conform precisely to American policy aims. In the case of Holder vs. Humanitarian Law Project, a group of American activists sought permission in advance before holding workshops to teach nonviolent political negotiation to a group listed as a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department. In this case, the groups involved were the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, or PKK, the militant Kurdish separatist group, and the LTTE, or Tamil Tigers, in Sri Lanka. The court ruled 6-3 that such assistance would violate American laws that prohibit providing material assistance to terrorists.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, it appears that Americans aren’t allowed to interact with listed terrorist groups, even to provide them the kind of assistance that on its face would appear to conform precisely to American policy aims. In the case of Holder vs. Humanitarian Law Project, a group of American activists sought permission in advance before holding workshops to teach nonviolent political negotiation to a group listed as a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department. In this case, the groups involved were the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, or PKK, the militant Kurdish separatist group, and the LTTE, or Tamil Tigers, in Sri Lanka. The court ruled 6-3 that such assistance would violate American laws that prohibit providing material assistance to terrorists.

I will write at greater length about this case later, and the many complicated questions that it raises. But right off the bat, it makes me wonder:

- Are the go-betweens who take messages to listed terrorist groups and report on their meetings to U.S. diplomats now legally liable?

- What happens if a listed terrorist group wants to abandon violence and learn politics? Who is allowed to advise them?

- Do journalists violate the material support law when they interview members of listed terrorist groups and publish their statements?

- When the U.S. government sends out feelers to listed terrorist groups, using intelligence operatives or other means, are they violating the law? Or is the government itself exempt? Or is a secret presidential finding necessary?

- If teaching terrorists about human rights law is equivalent in the eyes of the law to giving money to terrorists, what are the implications for free speech? Have words and money, political speech and military donations, become indistinguishable in the eyes of the law? What further avenues of prosecution would be opened such a finding?

The Supreme Court decision is here. Read the news story and the editorial in The New York Times, and other links on the homepage of the Humanitarian Law Project.

Team America’s New Boss

The McChrystal story really spiced up the week, and brought the Afghan war into a really clear focus. Matthew Yglesias wrote a fantastic short essay at The Daily Beast about what General David Petraeus needs to do to succeed. In the piece, Yglesias tackles two potent and related points. First, he gives voice to the counter-narrative about the Iraq surge, arguing that what Petraeus accomplished there wasn’t “victory” or a “secure Iraq” but a political triumph – lowering America’s expectations enough that Iraq’s disappointing progress would satisfy Washington and allow an exit. Second, Yglesias argues that Afghanistan is literally unwinnable, but could be another “success” if Petraeus can work the same magical concoction: great PR, political jujitsu, and competent war management.

As he says in summation:

Petraeus could be just the man to do for Obama what he did for Bush: help reframe the problem and walk away from unrealistic goals while projecting determination and making things better in some small concrete ways.

Hezbollah’s Flotilla?

Is Hezbollah outfitting blockade-busters to send to Gaza? It appears not, despite some breathless innuendo put forth by an Israeli think tank with close ties to Israel’s intelligence community.

Is Hezbollah outfitting blockade-busters to send to Gaza? It appears not, despite some breathless innuendo put forth by an Israeli think tank with close ties to Israel’s intelligence community.

The Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center in Israel put out a report on June 22 entitled “The aid flotilla planned to set sail from Lebanon is supported by Syria and Hezbollah.” The detailed analysis compiles lots of details about the organizers of two Lebanese boats that plan to sail to Gaza in defiance of Israel’s blockade. One of the organizers, Yasser Qashlak, appears in a clip on Hezbollah’s Al-Manar television network spewing racism:

A day will come when the ships will carry the remainder of the European garbage which came to my homeland [i.e., Israel] and return them to their homelands.

When it comes to the money point so boldly proclaimed in the headline, the Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center quite reasonably concedes (albeit far down, in paragraphs 15 and 16 of a 17-paragraph report) that it found no evidence to substantiate the claim that Hezbollah and Syria are behind the Nagi al-Ali and the all-woman-crewed Maryam.

Hezbollah is careful not to publicly affiliate itself with the Lebanese flotilla, out of fear of complications with Israel. Another reason is the understanding that it will harm their ability to represent the flotilla as reflecting a human rights effort. In response to many articles in the media, Hezbollah issued an explicit denial of its involvement. … The organizers of the ships repeatedly state in interviews with the media that they have no connections with Hezbollah.

That didn’t stop the Israel Defense Forces from trumpeting the report on its news page with the headline “Report: Hezbollah and Syria are organizing the Lebanese flotilla.”

Meanwhile the Lebanese flotilla organizers are finishing the process of getting clearance from the Lebanese government, which wants to stay as far away as it can from provoking Israel. The ships won’t fly the Lebanese flag, and they will sail first to Cyprus and only then to Gaza.

Lebanon and Israel officially remain in a state of war after signing a ceasefire in 1948. While Hezbollah – which is doctrinally committed to the destruction of Israel – dominates Lebanese politics, the government officially is under the leadership of Western-allied Prime Minister Saad Hariri, although one-third of its cabinet members come from Hezbollah and its coalition partners.

Hezbollah (like Hamas) has riled up its base about the Gaza blockade and the deaths of nine people aboard the Turkish ship that tried to bust it. The deadly episode on May 31 fit neatly into Hezbollah’s narratives about Islamic Resistance about “the Zionist entity.” Not least, Hezbollah cashed in rhetorically on the fact that religious Islamists fought Israeli commandos, thereby provoking a policy revision a few weeks later – the first relaxing of the blockade, and in the worldview of Hezbollah and Hamas, an achievement for Islamists on an issue on which secular Palestinians had failed to force any change.

Hezbollah (like Hamas) has riled up its base about the Gaza blockade and the deaths of nine people aboard the Turkish ship that tried to bust it. The deadly episode on May 31 fit neatly into Hezbollah’s narratives about Islamic Resistance about “the Zionist entity.” Not least, Hezbollah cashed in rhetorically on the fact that religious Islamists fought Israeli commandos, thereby provoking a policy revision a few weeks later – the first relaxing of the blockade, and in the worldview of Hezbollah and Hamas, an achievement for Islamists on an issue on which secular Palestinians had failed to force any change.

“Israel Preparing for Flotillas Like on Eve of War” screamed a June 23 headline on Al-Manar. (Hezbollah also threatened this week to sue the United States for libel, claiming that Washington and its Arab allies had spent $500 million “to bribe people to criticize Hezbollah.”)

Challenging the Gaza blockade is a popular unifying cause in Lebanon, appealing to nearly every constituency, even those who oppose Hezbollah. Defending Palestinian rights in Gaza also provides a welcome distraction for Lebanese politicians currently struggling with the matter of the second-class status of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

For Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s supreme leader and a gifted orator, the affairs of the boats and the siege have created a ripe opportunity to make rhetorical hay, and – once again – to position Hezbollah as the beneficiary of an effort to which it contributed nothing tangible. (Not unlike Hamas, the main, and perhaps unintended, beneficiary of the last flotilla.)

From Nasrallah’s most recent speech (translation by Al-Manar):

This is a lesson for some of those who preach the policy of humiliation, delusion and wishful thinking that only result in disgrace. On the other hand a policy based on power can accomplish a lot. …

There is a good chance today to end the blockade imposed on Gaza and this requires more Freedom flotillas. … We have to benefit from the Freedom flotilla to remind the world of Israel’s massacres

Can Stan McChrystal’s Campaign Be Saved?

The nail-biting saga of General Stanley McChrystal’s Rolling Stone interview has riveted a wide audience whose interest in Afghanistan had otherwise flagged. Shortly we’ll know whether he keeps his job, and the hyperventilating will subside over civil-military relations (On life support? Healthier than ever?).

The nail-biting saga of General Stanley McChrystal’s Rolling Stone interview has riveted a wide audience whose interest in Afghanistan had otherwise flagged. Shortly we’ll know whether he keeps his job, and the hyperventilating will subside over civil-military relations (On life support? Healthier than ever?).

McChrystal’s personality aside, however, the American government needs to figure out something much more urgent and important: Is his counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan working? Based on what we’ve learned in the last year, can it work at all?

President Obama hired McChrystal to turn around a war that had stagnated. He was chosen to execute a nimble counterinsurgency strategy, a campaign designed to stabilize Afghanistan and win popular support among Afghanis, harnessing military, political and economic policy.

The prior strategy wasn’t working – the Taliban had made a dramatic comeback in the years since the original invasion in 2001. Even the most vocal proponents of counterinsurgency doctrine cautioned that it had no guarantee of succeeding. To give counterinsurgency a fighting chance might require more troops, money and time than the United States was willing and able to give. (That caveat presaged some early advocates’ current view that there were never enough resources tasked to make a COIN campaign viable.)

Now the U.S. is a year into McChrystal’s plan: the halfway point to the summer of 2011 when the surge is supposed to end and American troop numbers will be reduced. So much has gone off script, however, that it raises questions about whether McChrystal’s blueprint still applies.

- President Hamid Karzai has broken ranks, frequently attacking his U.S. patrons in public.

- The Taliban has gotten stronger militarily.

- The first showcase offensive in Marjah has so far failed to stabilize the town or deny the Taliban sanctuary there.

- This summer’s major showcase offensive in Taliban-dominated Kandahar has been indefinitely postponed.

- Pakistan has derailed efforts to negotiate with the Taliban, even arresting the Taliban’s number-two when he held clandestine meetings with the United Nations.

All these events don’t prove that the U.S. can’t achieve its aims in Afghanistan – but that’s the conclusion to which they’re beginning to point. Counterinsurgency defines the toolkit the military brings to the fight; it doesn’t actually answer the question of what America should do.

Over the next year, if it hopes to establish some lasting stable order in Afghanistan, America will need a far greater unity of effort between its generals, its diplomats, its special envoys, and its friends in the Afghan and Pakistani governments. With or without McChrystal, the United States will have to make course corrections in Afghanistan as the war unfolds.

Quick briefing materials

Fred Kaplan at Slate argues that McChrystal and his loose-lipped team reveal a war effort spinning of control.

Leslie H. Gelb at The Daily Beast argues that the Democratic Party suffers from a permanent culture clash with the military.

Andrew Exum writes a thoughtful post about whether the assumptions behind the current strategy in Afghanistan still hold up. He also struggles with the implications of firing/not firing McChrystal in these two posts.

In the “Is History Repeating Itself?” department we have Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s post-mortem on the last general fired from running the Afghan year, just about a year ago.

And finally, the Michael Hastings article in Rolling Stone that kicked off the fuss, and which – the scandal aside – raises pointed questions about whether the counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan makes any sense.