Israel’s New Crisis at Sea

Writing at The Daily Beast, I look at what the future holds for Israel’s Gaza policy now that the Netanyahu government has decided to relax its blockade. I suspect even more challenges to the current legal arrangement which puts both Israel and Gaza in limbo. Read the whole piece here.

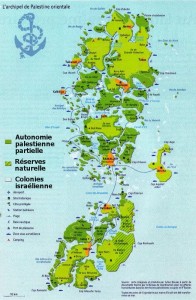

If the Netanyahu government translates Sunday’s statement into a substantially more open border with Gaza, they’ll find the calls for a new approach to Gaza just as shrill as ever—perhaps even more shrill now that Israel has backed down on one element of the blockade. What Gazans object to is that Israel claims to have ended any vestiges of occupation of Gaza when it pulled out the Jewish settlements in 2005—and yet, at the same time Israel retains control of Gaza’s sea and land borders.

That’s the nub of the problem, and not the shortage of foodstuffs and medicines. If Israel resolved Gaza’s humanitarian concerns, the Palestinians in Gaza would still be incensed that they can’t travel, import or export goods without Israel’s permission.

In other words, it’s not the cilantro; it’s the siege that’s the problem

Nonviolence, Hamas Style

Civil disobedience has enjoyed a renaissance among Palestinians, most vividly with Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s call for a boycott against Israel rather than armed resistance. (Adam Horowitz and Philip Weiss describe the “Boycott Divestment Sanctions Movement” in this long essay in The Nation. Matt McAllester theorizes in The Daily Beast about why non-violence has failed to win Palestinian hearts.)

It remains possible that civic and political action will replace rockets and suicide bombings as the weapon of choice for Palestinian activists. So far, though, Hamas doesn’t seem too interested. In conversations I had with Hamas officials during a reporting trip to Gaza in January, I encountered glib jokes and incomprehension rather than any serious engagement with the idea of non-violence.

Hamas had suspended support for suicide bombings against Israeli civilians, but only, officials told me, because such attacks were failing to produce the desired effects – not because they were wrong, illegal or counter-productive.

“There are two paths: the path of Gandhi and the path of Al Qaeda,” Hamas parliamentarian and spokesman Salah al-Bardaweel told me. When I asked him which one Hamas would take he paused and then said: “Al Q-andhi!” He bellowed with laughter at his joke.

He did add more seriously that “there are many types of resistance,” and that Hamas promoted social, political, and cultural efforts along with its military wing. He pointed out that some groups have splintered from Hamas because they didn’t consider it militant enough. Historically, Bardaweel argued, Palestinian organizations that focused exclusively on politics and culture at the expense of armed struggle lost popular support. “We are a resistance group, but we can’t let military actions spoil our entire political plan,” he said.

At a seminar for junior Hamas officials at the House of Wisdom, a think tank chaired by Hamas’s deputy foreign minister, a group of men in their twenties and thirties scoffed when I asked if they could imagine Hamas adhering to the Geneva Conventions and using the tools of non-violent protest.

One, a mid-level Hamas bureaucrat named Ahmed al-Najjar, didn’t even understand the concept. “Non-violence?” he said to me. “What have we ever accomplished by the throwing stones?”

An American colleague described the tactics of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. As the American talked, Najjar leaned over to me and chuckled. “Non-violence in this part of the world is nonsense. What do you want? We should stand in front of the Israelis shouting ‘No, no occupation, go, go, occupation’? Non-violence is nothing. It does not work.”

Hezbollah’s New Museum

Lebanon’s Party of God opened a museum last month in the village of Mlita. I haven’t visited it yet, but I’ve seen lots of Hezbollah’s temporary annual exhibitions, which are similar but on a smaller scale. The Mlita Museum appears to raise Hezbollah’s culture (or cult) of resistance and martyrdom yet another level.

Lebanon’s Party of God opened a museum last month in the village of Mlita. I haven’t visited it yet, but I’ve seen lots of Hezbollah’s temporary annual exhibitions, which are similar but on a smaller scale. The Mlita Museum appears to raise Hezbollah’s culture (or cult) of resistance and martyrdom yet another level.

Don Duncan has just posted an excellent short video on The Wall Street Journal’s website. The four-minute clip seems to give a good sense of the Mlita museum, which opened on May 23, on the tenth anniversary of Israel’s withdrawal from the zone it occupied in southern Lebanon.

From inside a 600-foot-long tunnel, visitors can peer through glass at some of Hezbollah’s former underground hideouts. The fortifications were closely guarded secrets until recently, and key to some of Hezbollah’s recent operations, including its fight with Israel in a brief 2006 war along the southern border.

To manage the new museum and other planned sites, Hezbollah is creating its own museum department, adding to its other divisions, which include radio and TV stations.

“It shows that the resistance is more stable,” said Muhammad Kawtharani, director of Hezbollah’s arts foundation and a spokesman for the Mlita museum project. “You’re seeing a secret that is a secret no more.”

The sprawling permanent museum appears to mark another step on Hezbollah’s march to institutionalize its “Society of Islamic Resistance.” Hezbollah’s resourceful approach to guerilla warfare and propaganda have allowed it to nimbly adapt to changing circumstances, but as its power and reach have expanded, so too has its tendency to create static state-like structures.

The Los Angeles Times had a piece in May when the museum first opened, and Hezbollah put up a piece on Al Manar’s website extolling the Mlita complex. Al Manar’s language captures the flavor of Hezbollah public relations and propaganda:

“Mlita is full of sacrifices and memories that led to the achievement of the final victory,” Adnan Ibrahim Sammour, one of the engineers in charge of the project, told Al Manar … “This is the new Middle East, the real new Middle East that we have always dreamt of.” …

Mlita is a first step in the long struggle of writing down the Resistance’s history, a shining history that cannot be summarized with words, pictures, or even experiences…

Hamas’ Tunnel Diplomacy

My letter from Gaza just went up on Foreign Affairs. In the piece, I describe the similar ways that Hamas has responded to economic and political isolation, in one case with tunnels, in the other case with their diplomatic equivalent. The web of tunnels underneath the Gaza-Egypt border turned an economic crisis for Gaza into a new sphere of influence for Hamas. I liken the approach — improvise and then pretend afterwards it was part of a strategic plan — to the way merchants solve problems.

My letter from Gaza just went up on Foreign Affairs. In the piece, I describe the similar ways that Hamas has responded to economic and political isolation, in one case with tunnels, in the other case with their diplomatic equivalent. The web of tunnels underneath the Gaza-Egypt border turned an economic crisis for Gaza into a new sphere of influence for Hamas. I liken the approach — improvise and then pretend afterwards it was part of a strategic plan — to the way merchants solve problems.

Here’s the thesis:

At first, in 2007, Hamas only tolerated the tunnel economy; but it began to embrace it the following year, legalizing and regulating subterranean trade. Hamas had found a spontaneous solution to the economic crisis that was threatening its rule of Gaza — and, in the process, turned expediency into opportunity.

Opportunism as strategy appears to be the group’s new hallmark. When faced with only bad options to deal with the blockade or its status as a diplomatic pariah, Hamas has behaved as if it chose its predicament, leveraging its position into either greater control over Gaza or greater political influence beyond its boundaries. Desperation, in other words, has become an avenue to power.

Click here to read the whole piece.

The Afghanistan Endgame

Brian Katulis at the Center for American Progress and Andrew Exum at the Center for New American Security tangled this week over Afghanistan strategy. Brian said the counter-insurgency community had hoodwinked Washington, and Andrew said that the Center for American Progress hadn’t presented compelling plans for Iraq and Afghanistan. Michael Cohen prompted the kerfuffle when he argued that the left had failed to question the war in Afghanistan and propose credible alternatives.

All of which got me thinking: can the think tank community propel a smart, substance-focused public debate about America’s strategic aims in Afghanistan? I have in mind a probing, impolitic assessment of whether the current tactics can achieve that strategy. CAP invited CNAS to take part in a public debate, which Exum said he we would happily join after returning from a dissertation leave. But I’d like to see these thinkers applying their brains to the big sprawling questions. Think tanks are largely extensions of different power constituencies in Washington, so perhaps it’s naïve, or structurally impossible, to expect them to re-frame the Afghanistan debate so that it includes more than the current two options: leave, or stay and fight, with some debate over the timeline and number of troops.

I expected this kind of vigorous reappraisal in 2009, during the Obama Administration’s Afghanistan policy reviews. However, the government ended up focusing on narrow questions, like how many troops were required to execute a counter-insurgency strategy, and on what timeline American troops should withdraw. The public never heard an airing of the underlying strategic questions:

- What tactics have been most effective at killing, capturing or deterring individuals and organizations whose goal is to conduct terrorist attacks beyond Afghanistan’s borders?

- What is America’s desired end-state in Afghanistan and Pakistan? Is it achievable, especially considering Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s drift away from the U.S. and Pakistan’s internal problems?

- If not, can America disentangle itself from Afghanistan in its tenth year of war there, even without achieving its principal war aims?

- If the U.S. cannot midwife a stable Afghanistan (or Pakistan) then what is the most effective way to combat the international terrorist groups currently thriving in the borderlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan?

These questions are tough, and probing honest answers would probably require the defense and South Asia experts to jettison some of their previous conclusions and criticize the policies of some of their friends and colleagues. But it would be a healthy and illuminating discussion at a moment when the course set largely by General Stanley McChrystal’s report last fall seems not to be yielding the desired results.

War Without Sacrifice

John Levi Barnard has written a powerful appeal to for us to take moral heed of the oil geyser in the Gulf of Mexico, abandon our wasteful ways, and embrace a kinder new paradigm.

There is a lesson to be learned here, as there was from the crisis of the 1850s, which is that there is a clear choice to be made between principle and the expedient solution, which is never a solution at all. Every president from Reagan to Obama has assured us that the American way of life is not negotiable, much as the great compromisers of the antebellum period assured us that nothing, not even Justice, would threaten the cohesion of the “union.”

Thoreau countered this in no uncertain terms, declaring in “Resistance to Civil Government” that the American “people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.” From the crisis in the Gulf of Mexico—which extends both literally and figuratively to the Persian Gulf and the borderlands of Pakistan—we can derive a similarly radical statement: we must stop drilling in the ocean though it costs us something at the pump, though it forces us to make our way of life negotiable.

A Viable Palestinian State?

A small group of technocrats has doggedly kept at the hard work of designing a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, long after the Oslo Process itself collapsed. Two of its longest serving advocates – Saeb Bamya, the Palestinian economist, and Ron Pundak, the Israeli director of the Peres Center for Peace – tried to answer the lofty (and perhaps rhetorical) question put forth by their host from The Century Foundation: After the Gaza blockade, can Palestine’s economy be viable?

A small group of technocrats has doggedly kept at the hard work of designing a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, long after the Oslo Process itself collapsed. Two of its longest serving advocates – Saeb Bamya, the Palestinian economist, and Ron Pundak, the Israeli director of the Peres Center for Peace – tried to answer the lofty (and perhaps rhetorical) question put forth by their host from The Century Foundation: After the Gaza blockade, can Palestine’s economy be viable?

The two men made a concerted and heartfelt pitch for a return to the ethos of building two states side by side. According to Bamya, more than anything else Palestinians need a “normal business environment,” which requires Israel and the Palestinian Authority to implement the 2005 agreement on access and movement that would free the flow of people and goods between the West Bank, Israel and Gaza. He and Pundak insisted that only a two-state solution could accommodate both Jews and Palestinians.

Daniel Levy, a fellow at the New America Foundation who was a member of Israeli negotiating teams in the latter stages of Oslo and at the 2001 Taba conference, tried without success to pin the two-staters down to specifics: How exactly would they like to Israel and the United States to relate, economically, to Gaza and the West Bank?

I asked Bamya and Pundak at what point they would determine that a self-sustaining Palestinian state was no longer viable. Their answer, it appeared, was that there was no such point. “Everything is reversible if there is political will,” Bamya said. Pundak added, “We are basing everything on the solution of two states.”

The final questioner, retired Pakistani diplomat Ahmad Kamal, said he hated to appear impolite to the panelists, but said he thought all their assumptions were specious. In the long run, Kamal said, a Palestinian state “dissected” between two unconnected geographical regions, Gaza and the West Bank, would never be sustainable; nor, he said, was an Israel that had hostile relations with its neighbors and which depended on the backing of the United States. “What about the possibility of a one-state solution?” Kamal asked.

“One state won’t happen,” Pundak said emphatically. “We hate each other too much. We will kill each other.”

“I won’t kill you,” Bamya said, provoking some laughter.

“Our grandchildren who don’t exist yet would kill each other,” Pundak earnestly replied.

“Inshallah,” said Daniel Levy, bringing down the house.

Islam’s Beginnings

The first followers of Christ didn’t consider themselves ’’Christians’’; they were Jews who believed that a fellow Jew named Jesus Christ was the long-awaited messiah. It took centuries for Christianity to evolve and solidify as a distinct faith with its own doctrine and institutions.

The first followers of Christ didn’t consider themselves ’’Christians’’; they were Jews who believed that a fellow Jew named Jesus Christ was the long-awaited messiah. It took centuries for Christianity to evolve and solidify as a distinct faith with its own doctrine and institutions.

In ’’Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam,’’ University of Chicago historian Fred M. Donner wants to provide a similar back story for Islam — a religion which, in the popular imagination, sprang wholly formed from the seventh-century sands of Arabia. Mohammed preached at the juncture of the Roman and Sassanian empires, winning support from Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and various deist polytheists. According to Donner, Mohammed built a movement of devout spiritualists from many faiths who shared a few core beliefs: God was one, the end of the world was near, and the truly religious had to live exemplary lives rather than merely pay lip service to God’s laws. It was only a century after Mohammed founded his ’’community of believers” and launched the great Islamic conquest that his followers started to define their beliefs as a distinct religious faith.

Devout Muslims — who model their lives directly on the mores of the Prophet and his companions — will be surprised to read that Mohammed welcomed Christians and Jews into his monotheistic movement. In fact, Donner suggests, the entire narrative of Islamic conquest misinterprets the ecumenical nature of the early believers. Mohammed, it appears, didn’t require his followers to renounce their religion; early Islam, in this read, was more a revival of existing faiths than a conversion.

Tariq Ramadan in the New World: The Atrophied Debate About Islam

Six years after the U.S. government banned him from the country, the celebrity Islamic scholar Tariq Ramadan landed in New York last week. The American government’s decision to reverse the ban marked a great victory for free speech advocates. Sadly, though, the conversation on stage suggested that a decade since the launch of the “Global War on Terror” (and despite the panelists’ best efforts) our public discourse is still distorted by the kind of thinking that begins with the question “Why do they hate us?” and unfolds with the false sense that the world’s billion-plus Muslims function as a monolithic and fanatical bloc.

Ramadan’s first public appearance, at Cooper Union in downtown Manhattan, had the kind of pomp and fanfare rarely associated with an intellectual event. People lined up around the block and paid $15, more than the price of a movie, to hear Ramadan and four other intellectuals brush every hot-button issue concerning the intersection of Islam and the West. Can Muslims loyally embrace Western secular governments? (Ramadan says of course.) Does Islam have a fundamental problem with women? (Historian Joan Wallach Scott says Westerners who care little for women’s equality in their own societies project their feminist discourse onto the Islamic world.)

Underlying the entire discussion was the general suspicion among some intellectuals on both the right and the left that Islam is fundamentally illiberal, and therefore incompatible with values like secular government, religious pluralism, and free speech. Tariq Ramadan – in part by choice, in part by happenstance – has been cast in the role of spokesman for “moderate Islamism.” He’s an Oxford professor; he’s religious; he’s the grandson of the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood; he’s a Swiss citizen of Egyptian origin; he’s a prolific writer; and he vigorously engages in the public sphere. At one time or another he’s confronted most questions about Muslims and their role in the West, and he’s left behind an ample public record to pick through. As a result, he’s become a favorite sounding board/punching bag/totem for people who argue about Islam and the West.

It’s only the beginning of his dialogue with the American public, and this first appearance was meant as much to celebrate the lawsuit that lifted Ramadan’s visa ban as it was to debut a serious discussion about Islamism in America and Europe. Despite the panel’s title – “Secularism, Islam and the West” (you can listen to the full audio here) – some questions seemed stuck in America’s first encounter with Islam after Sept. 11: Do you think it’s wrong to stone women? Does Islam countenance homosexuals? (Ramadan answered in the affirmative.)

The problem with such questions is that they presume first that Ramadan speaks as a religious authority, which he does not, and second that contemporary American political debates apply to the Islamic world, and should be used to frame some inquest into whether “Muslims,” as if they are a single entity, are good or bad. This “What went wrong?” ethos presumes that the fundamental matters of concern in the Islamic world, and among Muslim communities of the West, include gay rights, and whether women can drive or should be subjected to Taliban-style religious law. In fact, in the vast un-free zones of the Islamic world, people chafe at much more basic problems: the absence of any political rights, the lack of basic governance, stifled development, and in many places, widespread violence. Similarly, in the West, despite the outsized attention paid to extremists, the vast majority of Muslims agitate neither for religious rule nor for the cultural fundamentalism of the fanatics in Al Qaeda, the Taliban and the Shabab. When we want to engage the problem of violence and religious fanaticism meaningfully, we ought to do so with specificity. Do not ask “Why do they hate us?” Ask “What draws certain middle class youth away from politics and into the nihilistic violence of Al Qaeda?” or “Why do certain religious thinkers rule it’s okay to target civilians in a time of war?”

A more interesting debate began, when George Packer, a writer for The New Yorker, politely but with determination confronted Ramadan about his grandfather. What did Ramadan have to say, Packer asked, about his grandfather’s embrace of a Palestinian leader who had collaborated with the Nazis? Packer invited Ramadan to condemn the World War II-era mufti of Jerusalem for his Nazi sympathies, and also to go a step further and condemn his own grandfather, Hassan al-Banna, for embracing the mufti and ignoring the mufti’s work on behalf of the Nazis.

This question might seem obscure, but it raises a lot of the baggage with which the West often saddles Islamists and Palestinian activists – and which many of those same activists in turn have failed to confront and discard. Many Western liberals (and many Israelis, and many secular Muslims) believe that a profound stream of anti-Semitism and authoritarianism courses though Islamism. Those Islamists who engage in the debate reply that they oppose Israeli policy and not Jews, and that they would not govern in the dictatorial manner of Islamic movements like the Taliban or Al Qaeda. Supporters of a Palestinian state feel unfairly bludgeoned, held to a standard of historical perfection spared supporters of Israel: Why, they ask, do they have to account for their forebears’ behavior in the 1930s and 1940s while the world gives Israel a pass on the record of the Irgun and the Stern Gang? That question merits another essay, but in short, there’s plenty of public discussion about Israel’s (and the West’s) legacy of violence, and morality is not a zero-sum game. You don’t have to wait for your political rival to acknowledge right and wrong and confront a troubled past before asking yourself tough questions.

The problem comes in cases like that of the mufti of Jerusalem, or the waffling of Hassan al-Banna. Why don’t Islamist activists go out of their way to condemn their predecessors’ mistakes, or the excesses (or racism) of some of their peers? It’s fair enough that Ramadan wants to put the mufti’s actions in their historical context, just as many Palestinians and other Middle Easterners want to contextualize the acts of various militants in the ongoing war between Palestinians and Israel. But the quest for context need not prevent those advocates from decrying actions that are clearly wrong or misguided. The Palestinian case, presumably, does not rest on the infallibility of its leaders and its gunmen. Nor should proponents of a Palestinian state fear they would jeopardize their case if they were to condemn support for the Nazis, or for that matter, the targeting and killing of civilians. There are plenty of Palestinian, Islamist, and, for that matter, Israeli, constituencies that roundly condemn historical errors and criminal conduct by their fellow partisans; in the case of activist Islamism, however, such arguments are rarely heard from the leadership.

In Ramadan’s case, he’s neither a political leader nor religious jurist. The claims of his most vociferous critics notwithstanding, he’s neither two-faced nor an apologist for extremism. (Ian Buruma’s New York Times Magazine profile explores Ramadan’s reputation as slippery; Laura Secor in suscriber-only The Boston Globe archive chronicles Ramadan delivering the same message to Muslim and non-Muslim audiences.) However, as an articulate thinker who has assumed the burden of convincing Western Muslims that there is no conflict between their religious identity and their role as citizens of secular Western democracies – and as an interpreter between Islamism and the secular West – he is in a unique role to confront this quandary. He wants to be a bridge, and he seems to have the temperament and intellect to tackle that role.

Many Western critics, however, still aren’t interrogating Islamic thinkers and leaders with any granularity or nuance, talking as if all religious Muslims thought part and parcel with fundamentalist Wahabbis. A tract distributed at the event by one Lorna Salzman entitled “The Muslim Suppression of Free Speech: An Abridged History” comes from that blinkered tradition. Ramadan himself is a victim of “Muslim suppression of free speech,” if properly understood; in addition to being banned from the United States for so many years, he is still prohibited from speaking in six majority-Muslim countries. Their authoritarian rulers clearly consider the Oxford professor a greater threat than the West does. For his part, Ramadan should take head on this well of doubt about the Islamic world’s contemporary history and problem with violent extremists, and craft an unapologetic response that doesn’t fear apologizing when appropriate. Dialogue and a more nuanced view of Islam by the skeptical quarters of the West won’t begin until both parties have taken a step closer to the riverbanks from which they contemplate one another.

Hamas U.

GAZA – Behind the arabesque arches of the five-story university library here, students occupy every available seat, cramming for finals in their humanities classes. Outside, a lucky few nap beneath palm and ficus trees on the cramped urban campus. At lunch, engineering students balance their books upright in the cafeteria and absent-mindedly munch subsidized falafel. This is exam period at the Islamic University of Gaza, charged with the bustle and anxiety of college life.

The first sign that this is a different place from the Western universities it resembles comes when a bell rings in the library. Quickly the students on odd-numbered floors – all men – gather their books and file into the stairwells. Women file in to take their turn. In keeping with a puritanical interpretation of Islamic law, men and women aren’t allowed to study together, so they switch floors every two hours. They lounge in separate student unions and eat in separate cafeterias. At intervals during the day, the call to prayer sounds from the minarets of the campus mosque, and classes come to a halt.

Their strict observance might sound extreme, but the Islamic University is no fringe institution: It’s the top university in Gaza. The majority of students here study secular topics; not all of them are even religious. If you want to get a degree in Gaza, a territory that is home to more than a million people, it’s simply the best place to go.

At the same time, the university is something else again: the brain trust and engine room of Hamas, the Islamist movement that governs Gaza and has been a standard-bearer in the renaissance of radical Islamist militant politics across the Middle East. Thinkers here generate the big ideas that have driven Hamas to power; they have written treatises on Islamic governance, warfare, and justice that serve as the blueprints for the movement’s political and militant platforms. And the university’s goal is even more radical and ambitious than that of Hamas itself, an organization devoted primarily to war against Israel and the pursuit of political power. Its mission is to Islamicize society at every level, with a focus on Gaza but aspirations to influence the entire Islamic world.

In recent decades, as Islamism has grown from a set of isolated radical movements to a fully realized political philosophy, its powerful fusion of intellect, pragmatism, and fundamentalist faith has refashioned societies from the Gulf to Turkey, Egypt to Pakistan. For outsiders who want to understand its power and appeal, the Islamic University of Gaza is probably the best place to begin.

When the Islamic University was founded in 1978, there wasn’t a single institution of higher education in the Gaza Strip. Its founders were members of the militant Muslim Brotherhood, believers that society should be organized according to Koranic principles, and they conceived the university as a sort of greenhouse for their brand of pure, uncompromising Islamism. At the time, Gaza was a freewheeling resort city, its seaside restaurants full of visiting Israelis and Egyptians attracted by Gaza’s famous grilled fish. Secular Palestinians dominated society and the power structure in the 1970s, and scoffed at the prospect of Islamists making inroads. Read the rest of the story in The Boston Globe’s Sunday Ideas section…